New York City — 4 Incredible Art Museums

GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM, NEW YORK

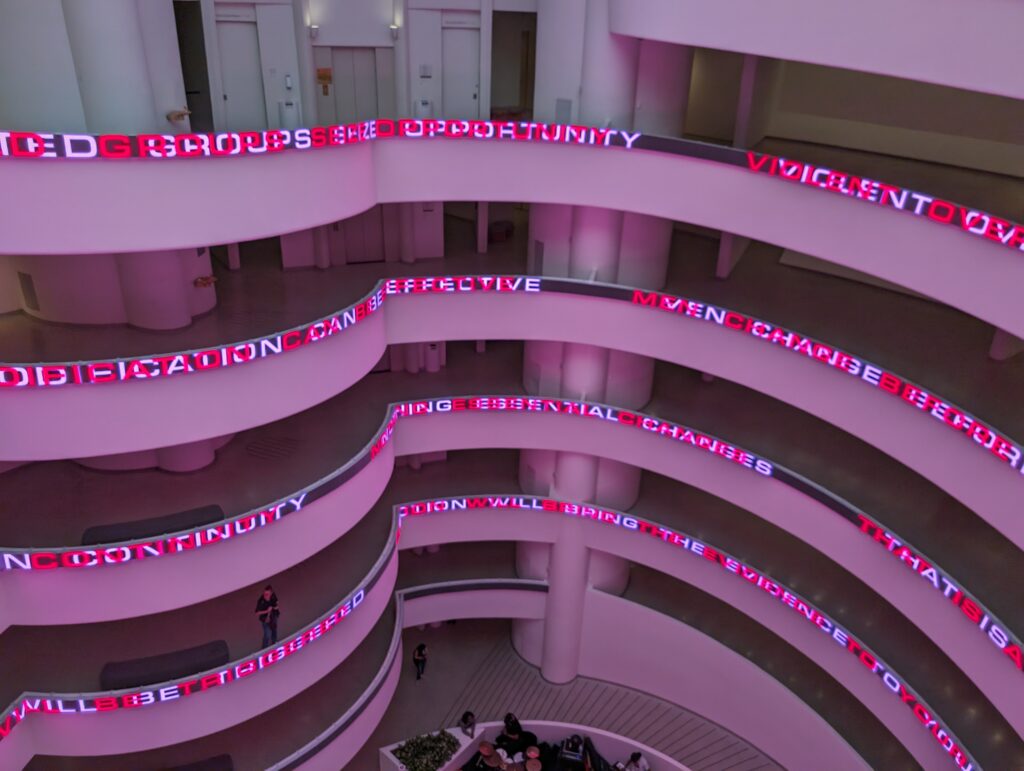

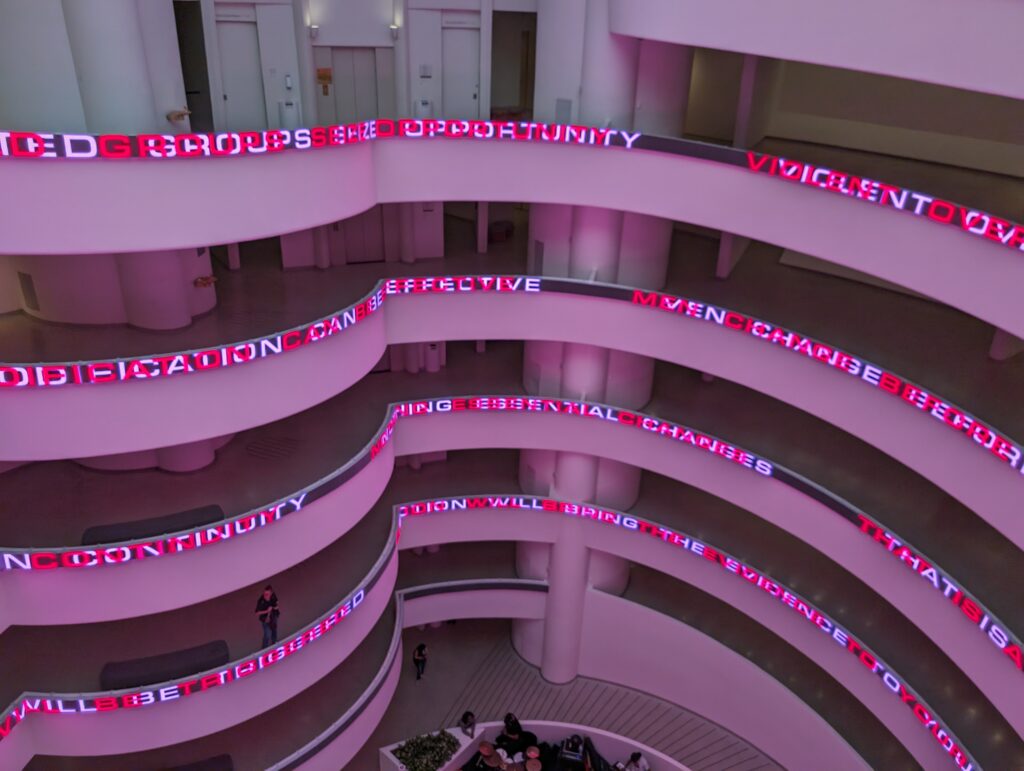

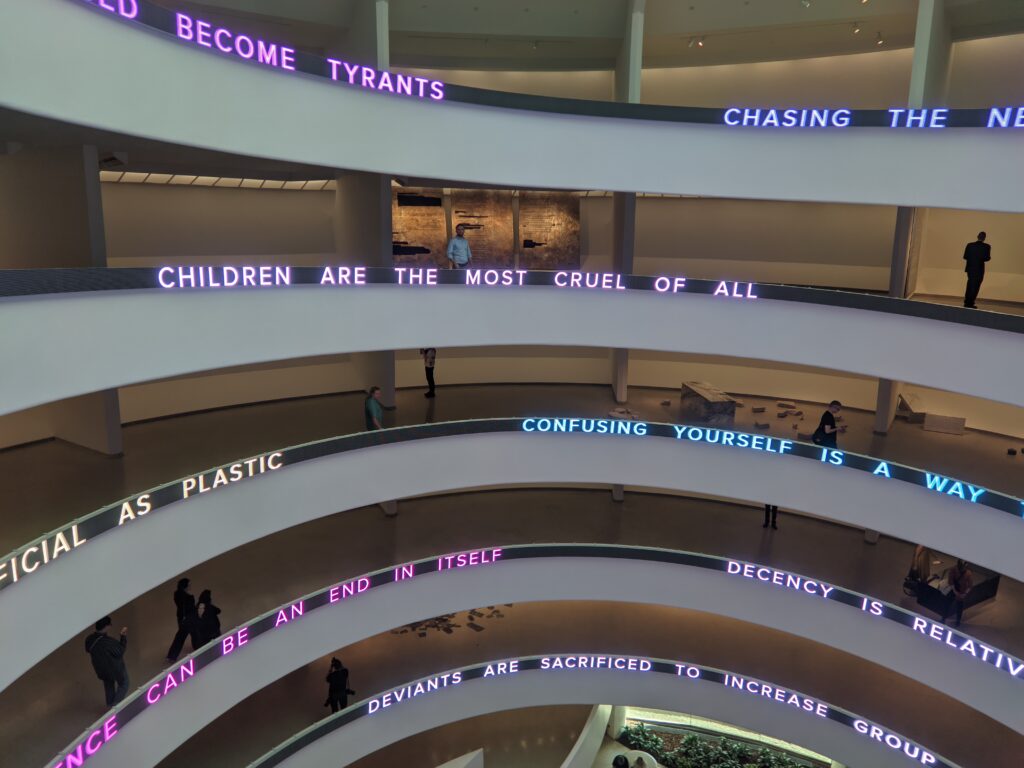

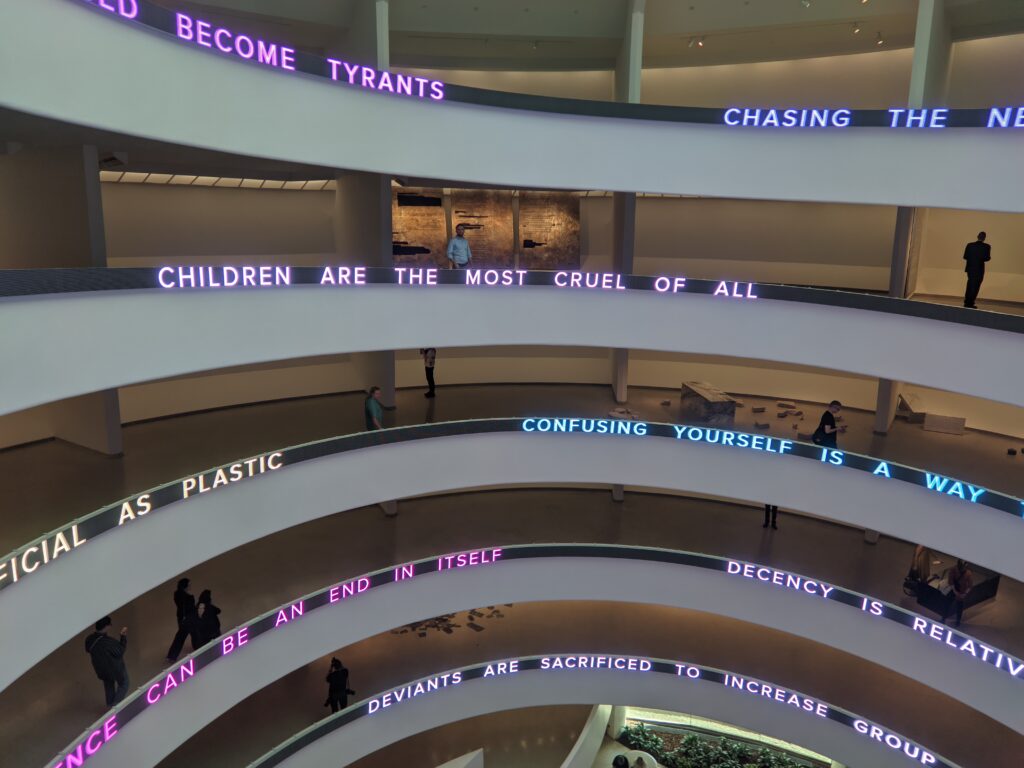

Now is the best time to visit the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. Through September 29, 2024, this unique space for showcasing architecture and visual art is presenting a special exhibit entitled “Light Line” featuring the art of Jenny Holzer. This building is the only structure in New York designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, and the only museum he created.

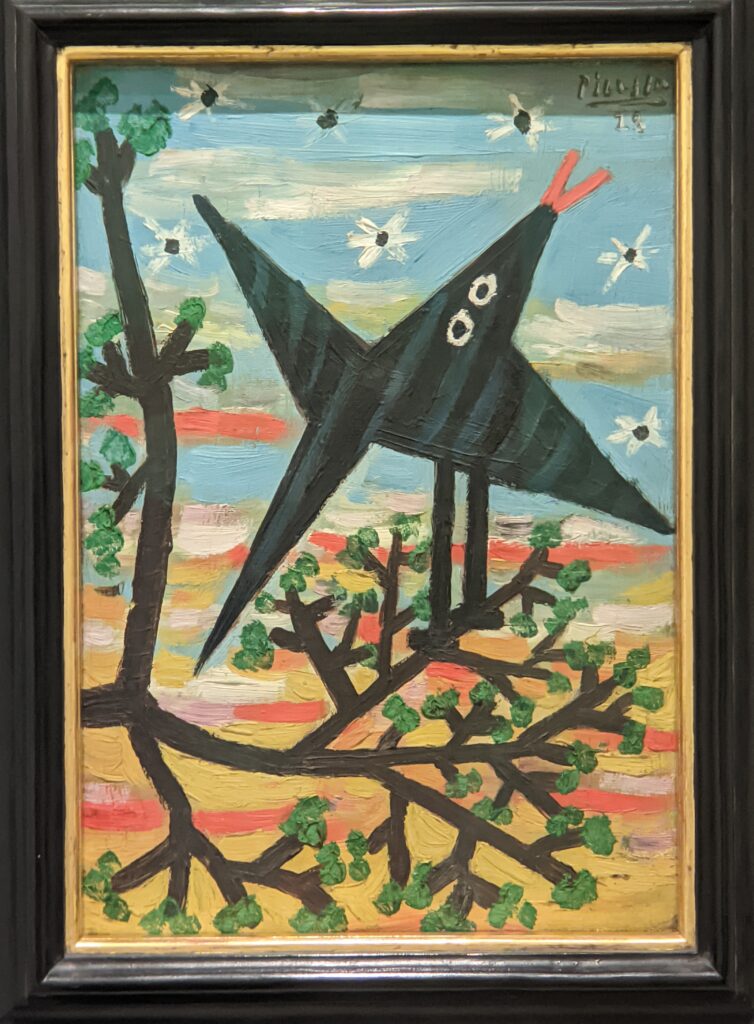

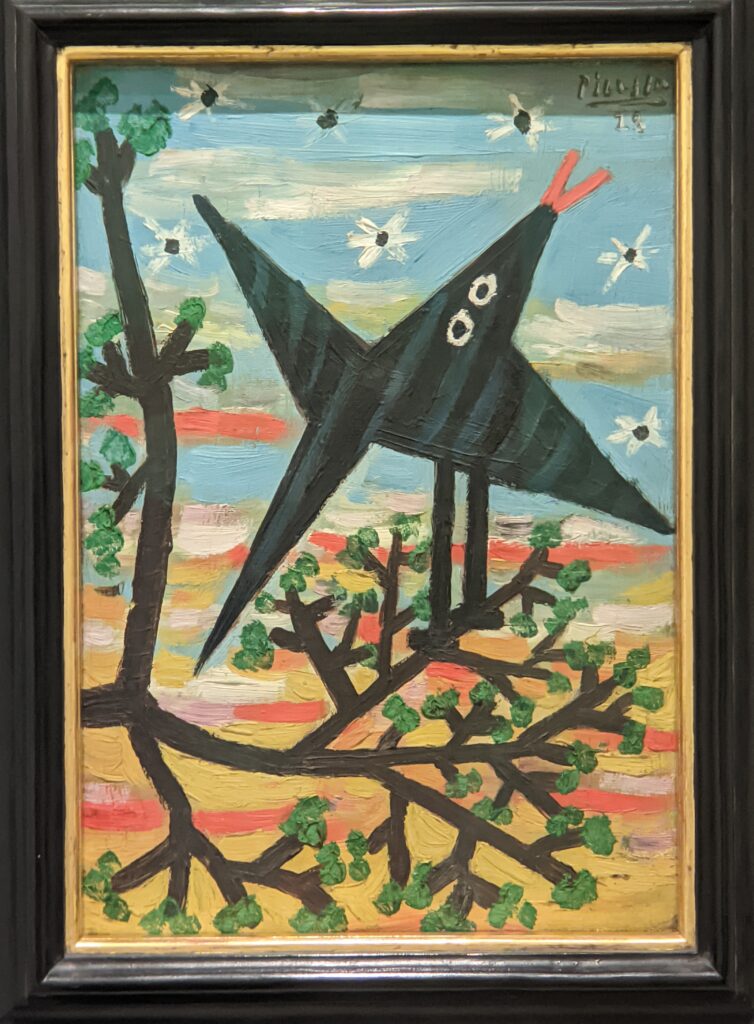

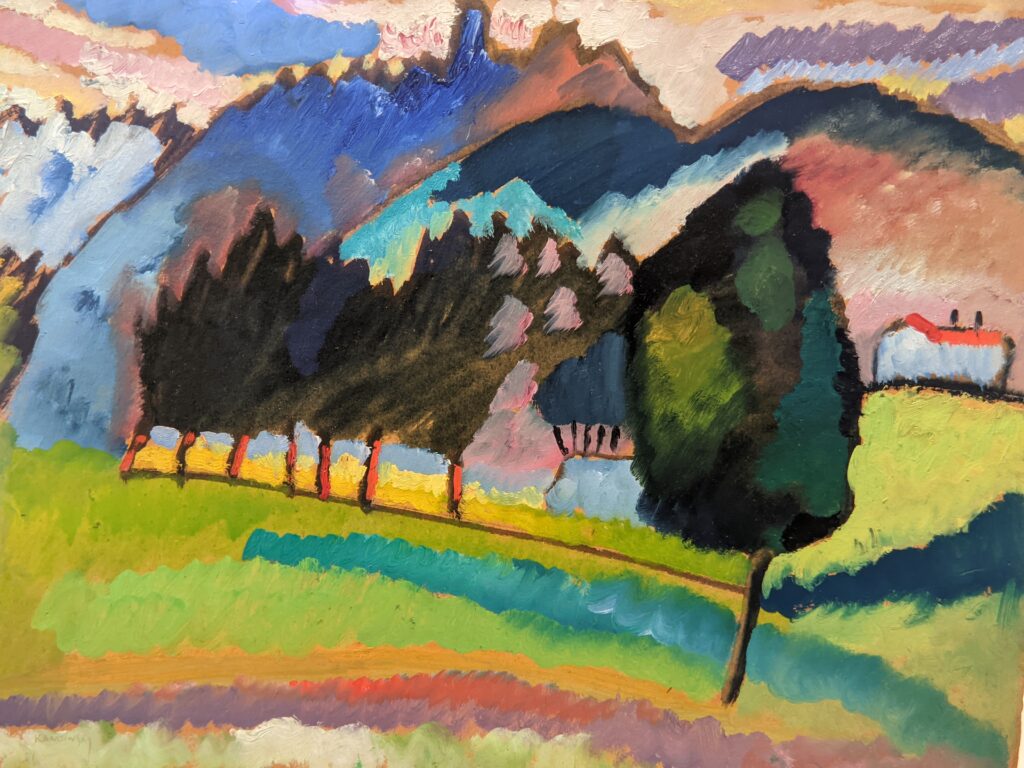

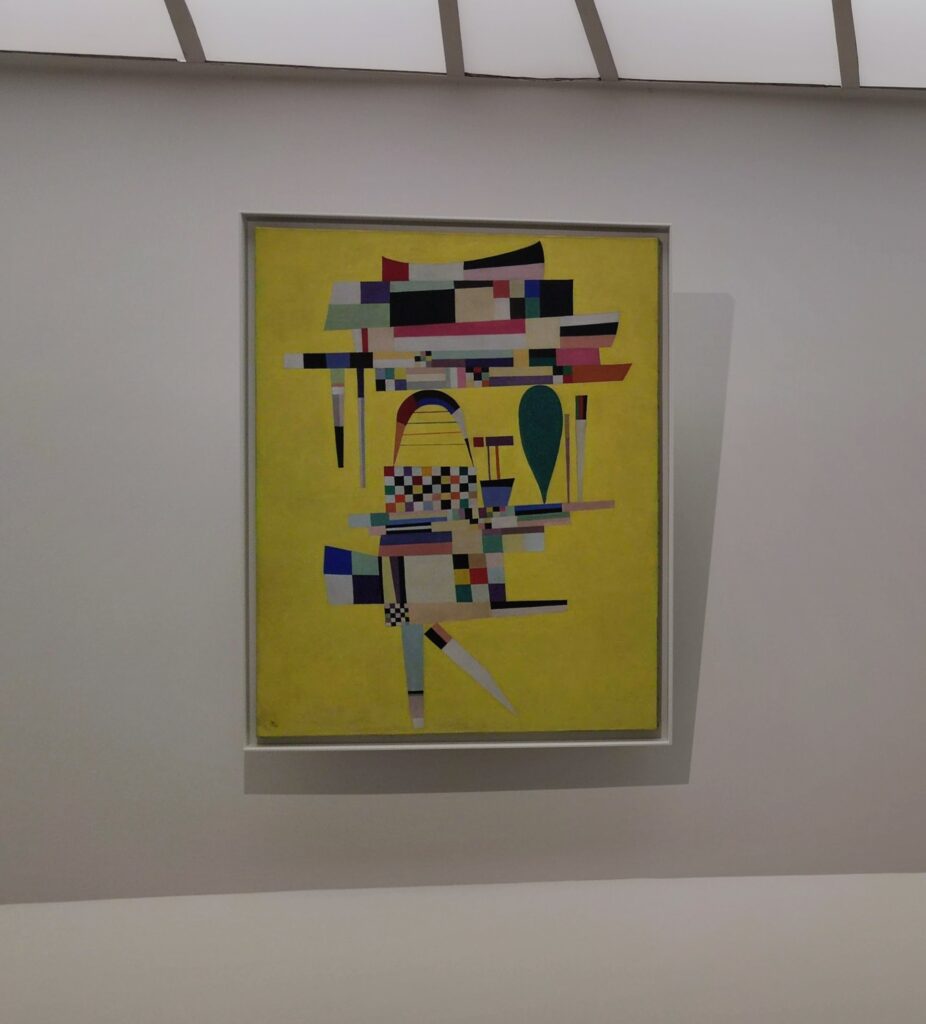

Completed in 1959, the Guggenheim took 15 years to design and construct. The museum’s unusual features drew controversy at first, but over time received universal praise. The permanent collection includes over 8,000 works of art, and specializes in early Modernism and non-objective art (including more than 150 paintings by Vasily Kandinsky). In 1963, the museum acquired the amazing Thannhauser Collection, broadening its holdings with Impressionist and Post-Impressionist masterpieces plus 32 works by Picasso, and now also collects contemporary art. This article discusses the following New York museums:

Guggenheim Museum, New York

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Frick Collection

The Museum of Modern Art

Normally we would not include the Guggenheim among the top four museums in New York for the simple reason that too few pieces from its fine collection are on public display. In addition, the unusual shape of the spaces designated for exhibiting paintings, sculpture and modern art along the museum’s six-story helical ramp means that not all exhibitions integrate harmoniously with the building’s iconic design. In fact, the limited wall space permits the museum to put on view only about 5% to 7% of its holdings. Fortunately, Jenny Holzer’s reimagination of the Guggenheim’s interior is intriguing and, in our opinion, exceptional!

The top level of the Guggenheim Museum is a great place to view art from a different perspective, and people watch!

The Architect & the Artist on 5th Avenue in New York

Frank Lloyd Wright, who welcomed this opportunity to experiment with his “organic” style in an urban setting, noted that he had never seen a “properly designed” museum and claimed that his Guggenheim would make the nearby Metropolitan Museum of Art “look like a Protestant barn.”

The genius of Wright’s design wonderfully asks more questions than it answers. Is a museum merely a venue for displaying the art within it? Should an architect’s dynamic vision for the interior and exterior of a museum building be too competitive for the proper presentation of art, or can such dynamism simply invite viewers to experience a new form of seeing? Jenny Holzer has provided some answers through her reinterpretation of this space in a new, challenging and thought-provoking manner.

Jenny Holzer’s pioneering artforms perfectly activate, complement and energize Wright’s visionary architecture.

“JENNY HOLZER: Light Line” Is on View in New York Through September 29, 2024

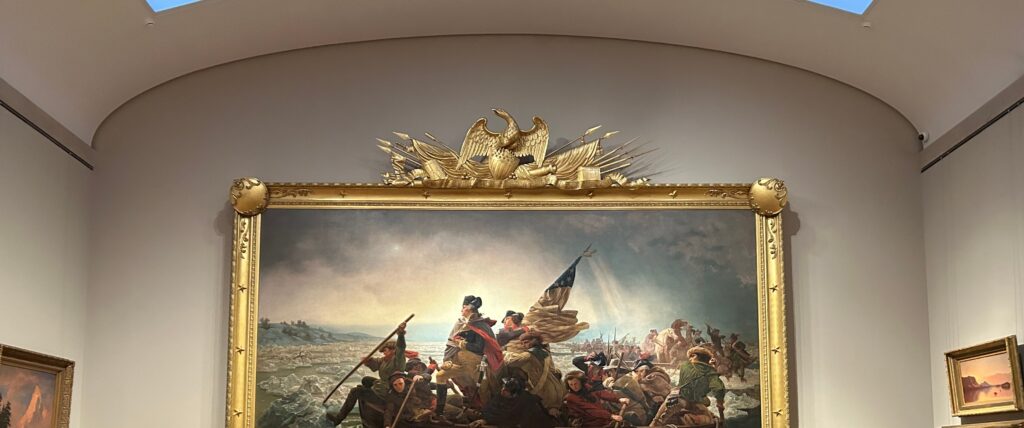

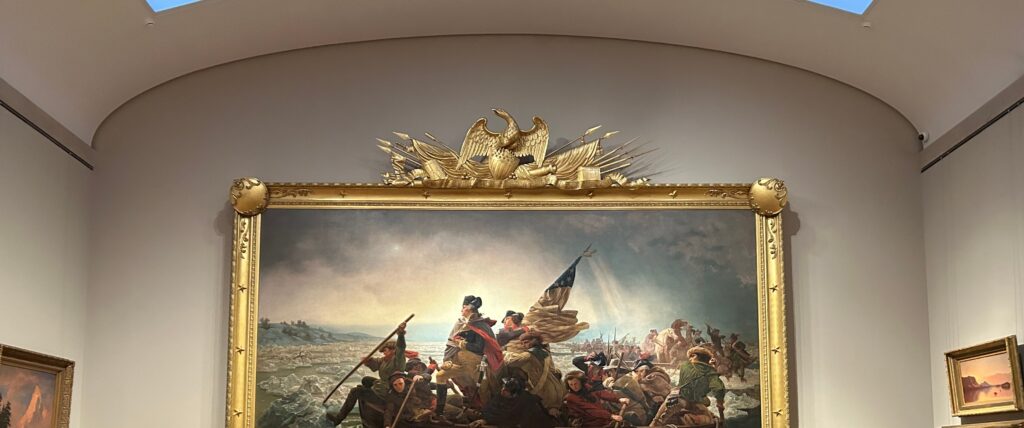

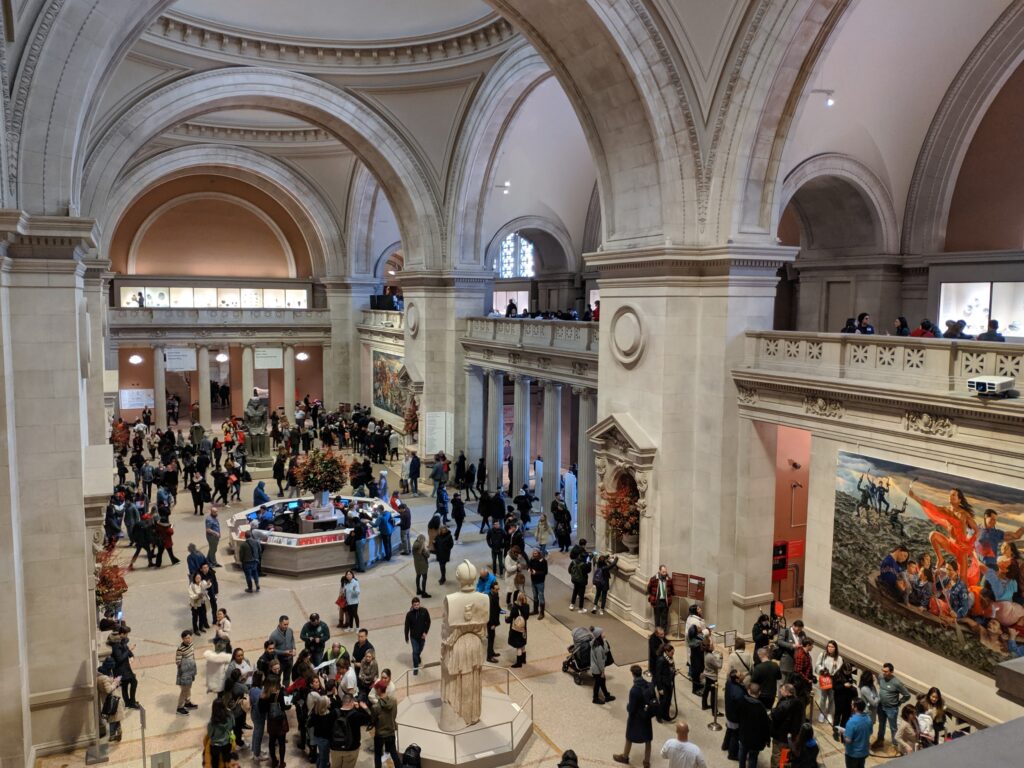

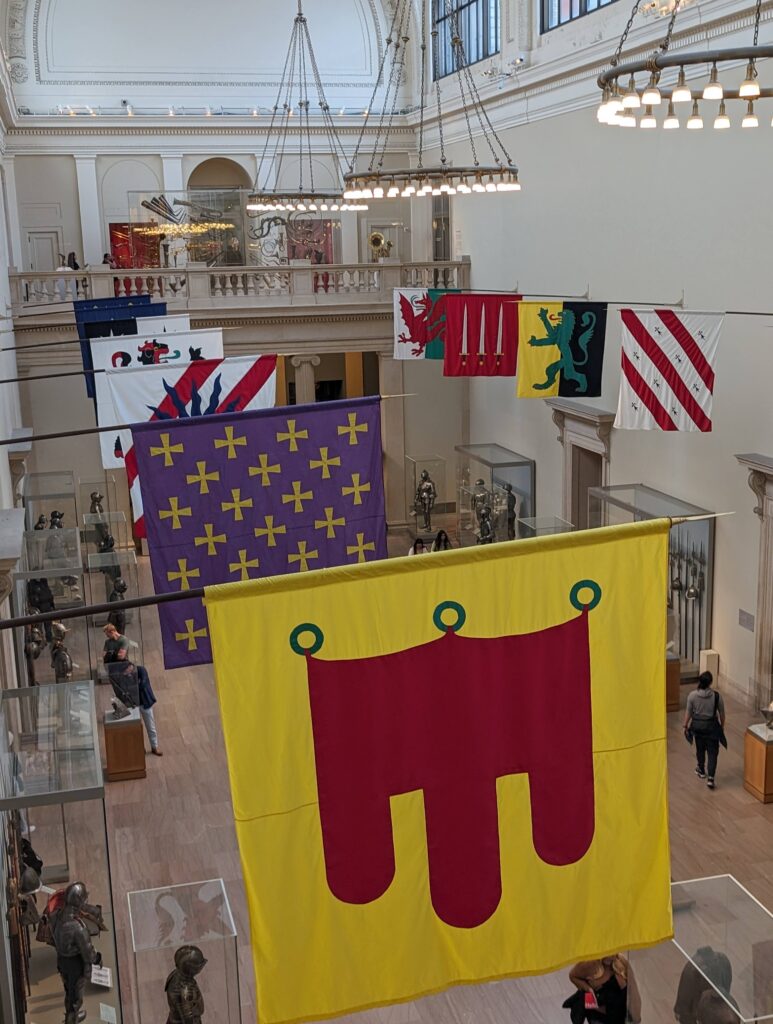

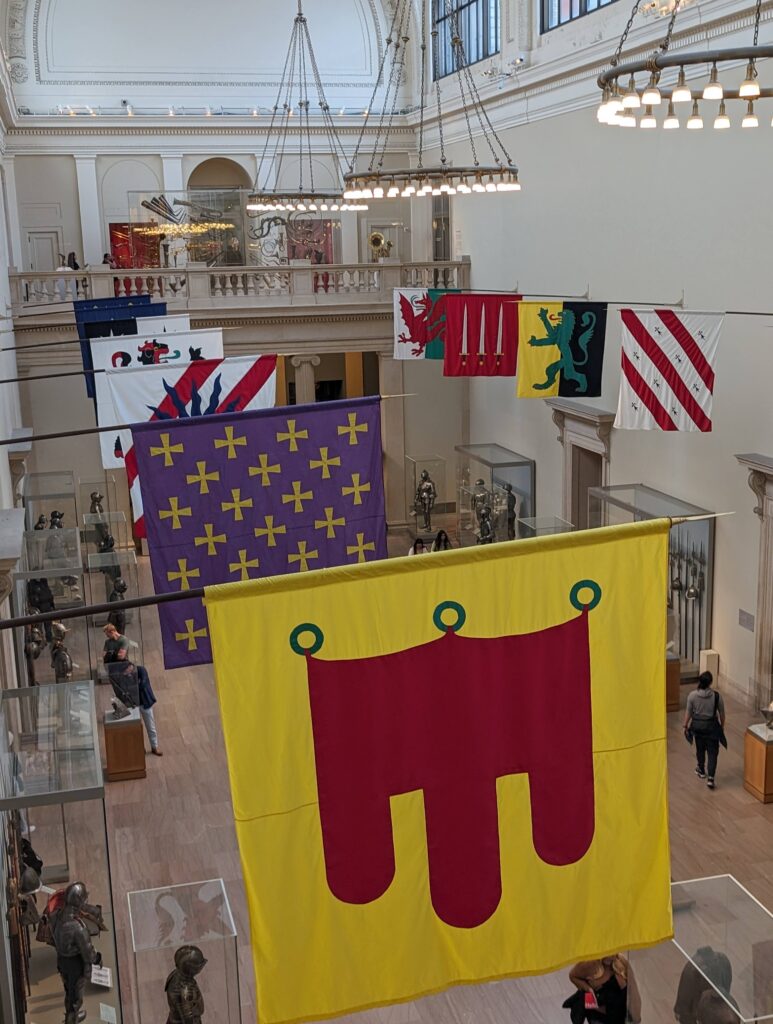

The METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART in NEW YORK

“You’ll probably need 3-5 hours just to see the permanent collection” at the Met, according to Go City, the largest multi-attraction pass company in the world. This is horrible advice. To make matters worse, Go City highlights “some of the best and most famous” areas at the Met Museum for you to walk through and suggests you start with Greek and Roman Art. Wrong!

We decided to set the record straight. How long does it take to appreciate the encyclopedic collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York? The correct answer is 3 to 5 days and, while the museum’s Greek and Roman galleries were expanded to 60,000 square feet (6,000 square meters) 15 years ago to display the majority of the antiquities collection, you should travel to Europe to enjoy the highest-quality objects from this period.

At The Metropolitan Museum of Art (colloquially “the Met”) we advise you to begin with Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art.

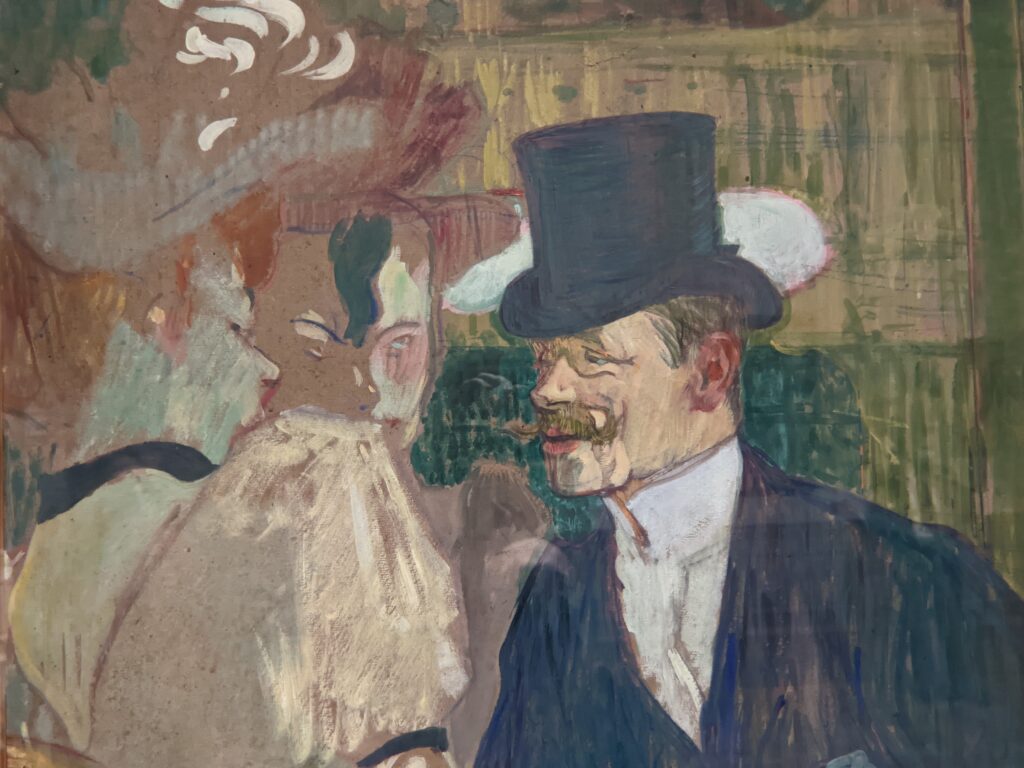

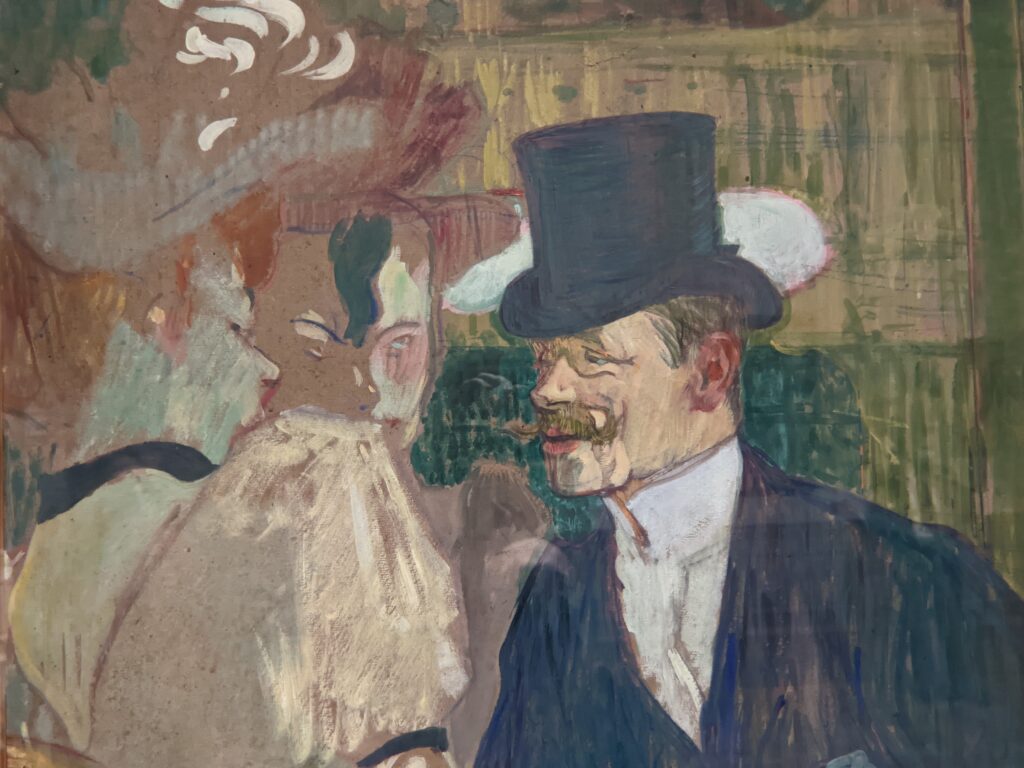

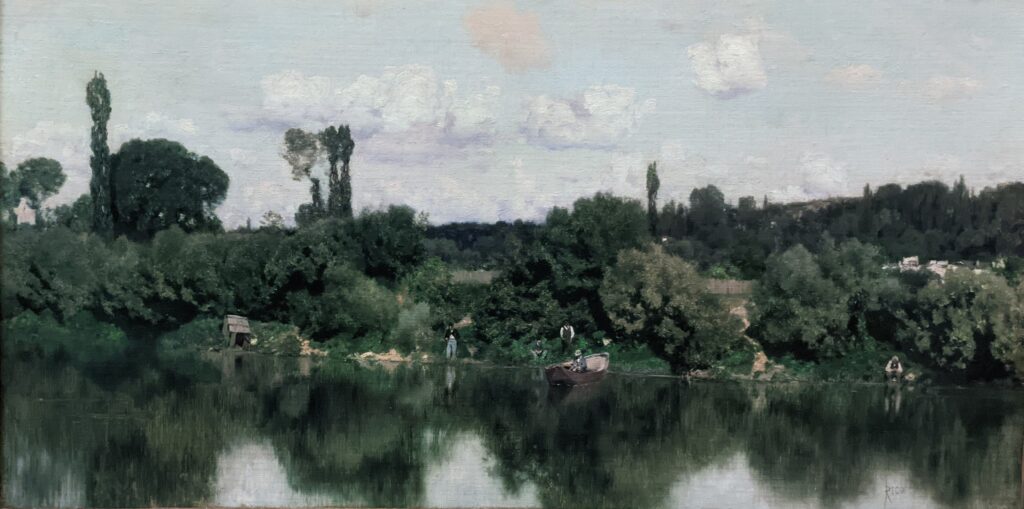

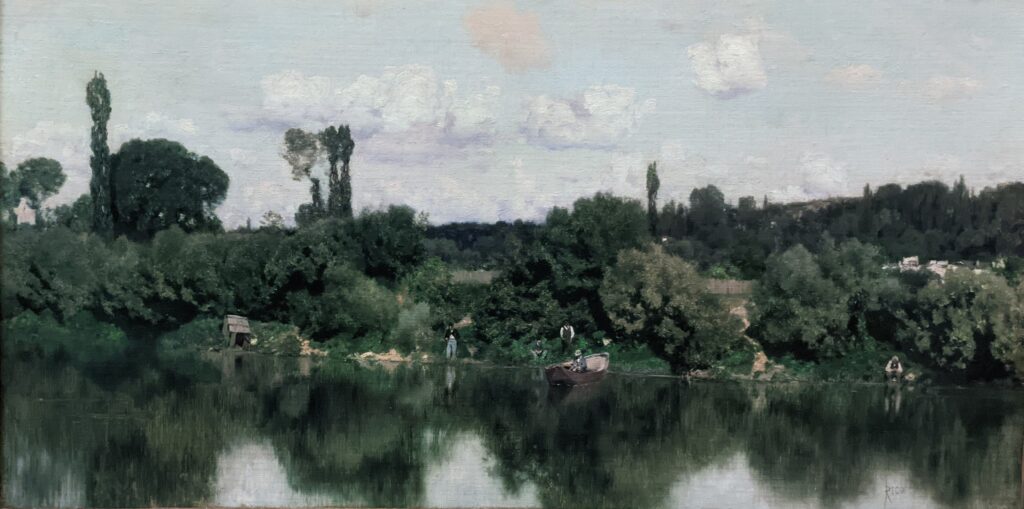

In the Impressionist galleries at the Met you will find paintings by Boudin, Jongkind, Daubigny and Rico y Ortega — painters who, in the 1860s, exerted a powerful influence on many of the young artists who would emerge in the following decade to lead a revolutionary movement in art. Curators at the Met include realist still-life paintings and a portrait (above) by Henri Fantin-Latour in these rooms, even though Fantin-Latour was not an Impressionist.

It is laudable, and helpful for art lovers, when art institutions exhibit seminal works by the likes of Édouard Manet and Fantin-Latour alongside the practitioners of the style we recognize today as the Classic phase of Impressionism. Even though their bodies of work lie on the periphery of Impressionism, their interest in the effects of light and choice of subject matter achieved, in spirit, nearly identical goals as Monet, Sisley, Renoir, Pissarro, Cassatt (below), Degas and Morisot.

Degas & the generation of artists that followed Courbet & Manet

Degas demanded a lot from himself as a painter, and he was disciplined — more than one-half of his output involved women and the opera. The ease with which he experimented with color and movement, combined with his regimented skills at observation, bring to mind the romanticism of Delacroix and the classicism of Ingres.

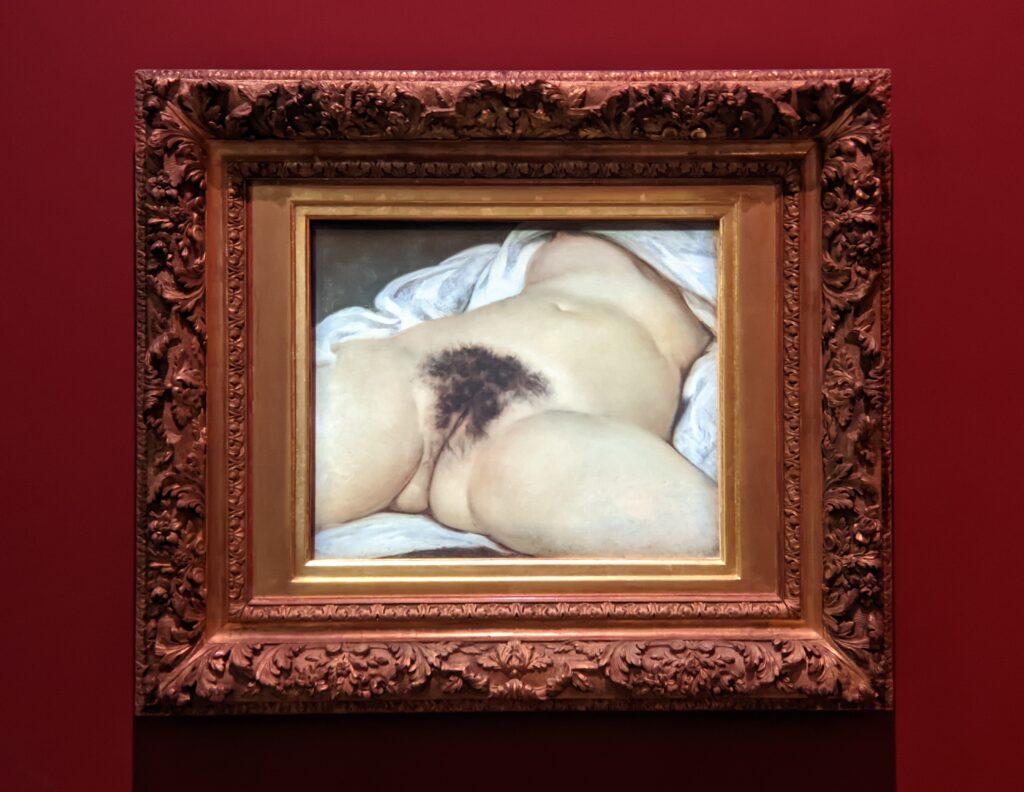

Gustave Courbet was perhaps the grandfather of Impressionism when he declared that his intention as a painter had been “to represent the customs, the ideas, the appearance of my own era according to my own ideas.” As the leaders of the French avant-garde 20 years after Courbet, the core members of the Impressionist movement including Edgar Degas set out to paint light (and life) as it actually appeared, rather than as artists were taught to interpret it solely from the confines of a school or a studio.

If Édouard Manet was the father of Impressionism, it was because Manet broke with convention in subject and style by focusing on contemporary life.

The example set by Manet allowed younger artists such as Degas and Monet to strike out in an independent direction, to break precedents — and, like Courbet, to commit themselves to the pursuit of contemporary realism. For Degas, this meant to venture beyond the precise gestures of the ballerina in order to capture the subconscious movements of the laundress, the cafe singer and the milliner in the modern urban life of Paris during the 1870s and 1880s, and to represent with genuineness the moods of these ordinary people.

The Met possesses the best Claude Monet Collection in New York

In 1867, painting a pure landscape or seascape was considered by the official Ecole des Beaux-Arts to be beneath the dignity of a serious artist. That did not stop the 27-year-old Claude Monet from writing to his friend Bazille that he was working on about 20 such canvases while on the Normandy coast during the summer. “Among the seascapes, I am doing the regattas of Le Havre with many figures on the beach and the outer harbor covered with small sails,” he wrote. The variety of blue and green shadows in Monet’s paintings from 1865 onward indicate the artist’s fascination with atmospheric conditions affecting light and color — a marked contrast from the formulaic and idealized approach to nature followed by painters trained at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in France.

Van Gogh preferred Monet’s painting of Sunflowers to his own

In Van Gogh’s 1888 letter to his brother, Vincent wrote, “Gauguin was telling me the other day that he had seen a picture by Claude Monet of sunflowers in a large Japanese vase, very fine, but — he likes mine better. I do not agree.” This 1881 painting of sunflowers (above) by Monet was included in the 7th Impressionist exhibition (held in 1882), and in 1886 it was one of the first Impressionist paintings to be exhibited in the USA. Today, there are more paintings by Monet in the United States than in any other country, and the Met owns at least 40 canvases from all periods of Monet’s long career, 30 of which are normally on display in New York.

The Road from Post-Impressionism to Modernism at the Met

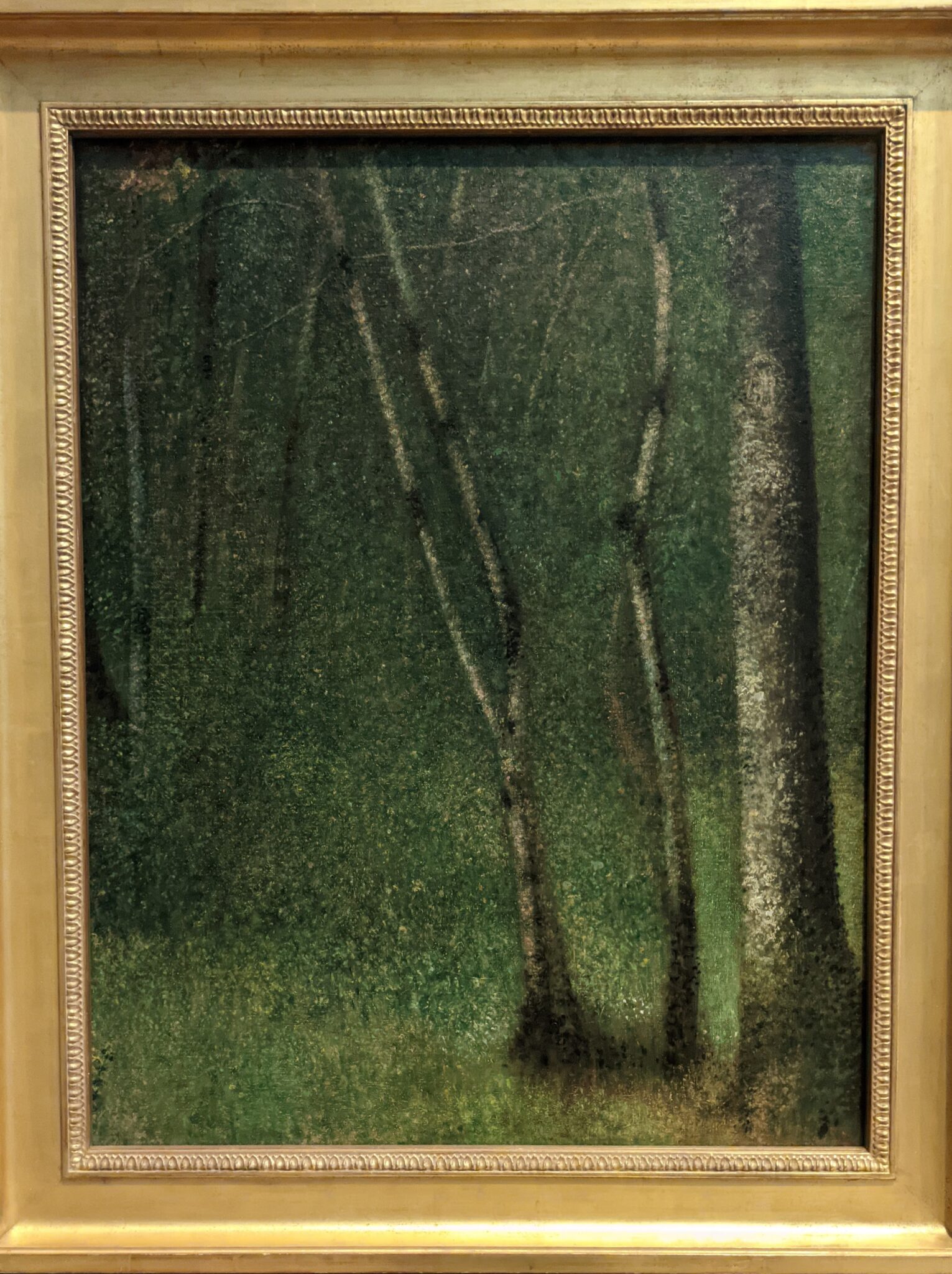

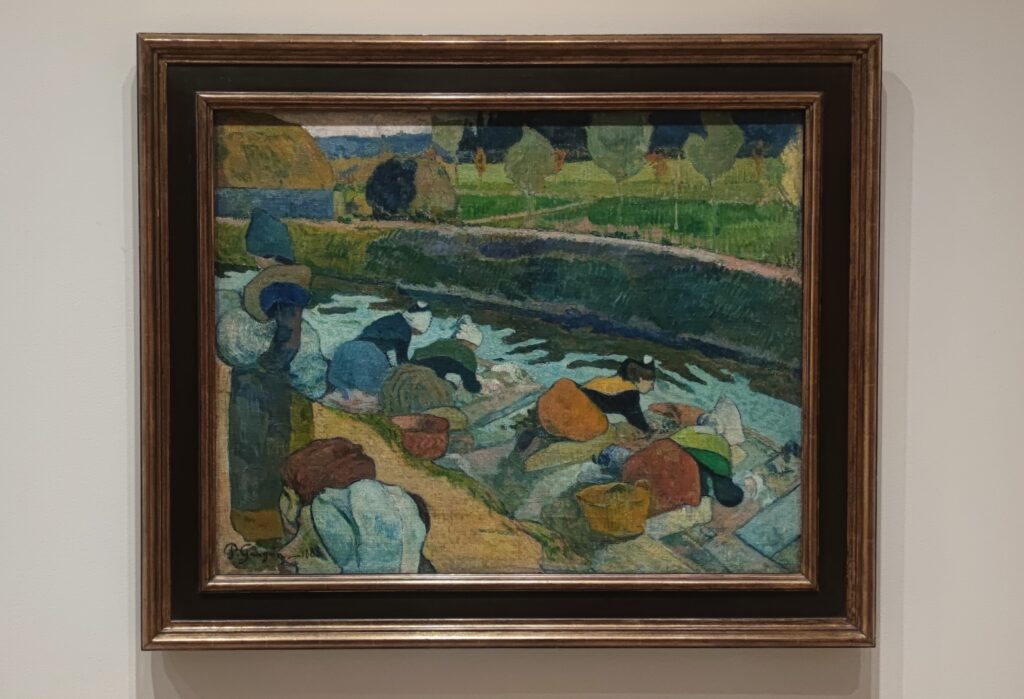

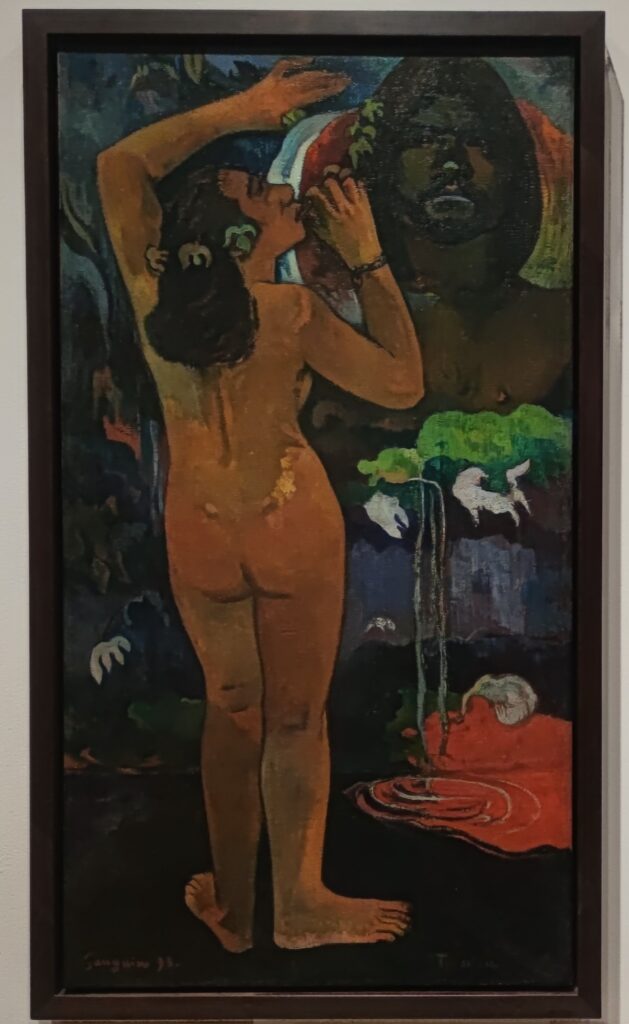

Paul Gauguin had a huge influence on the development of modern art in the beginning of the 20th century. While his sculpture and paintings were included in four of the eight Impressionist exhibitions, Gauguin ultimately rejected Impressionism and Pointillism for lacking symbolic depth.

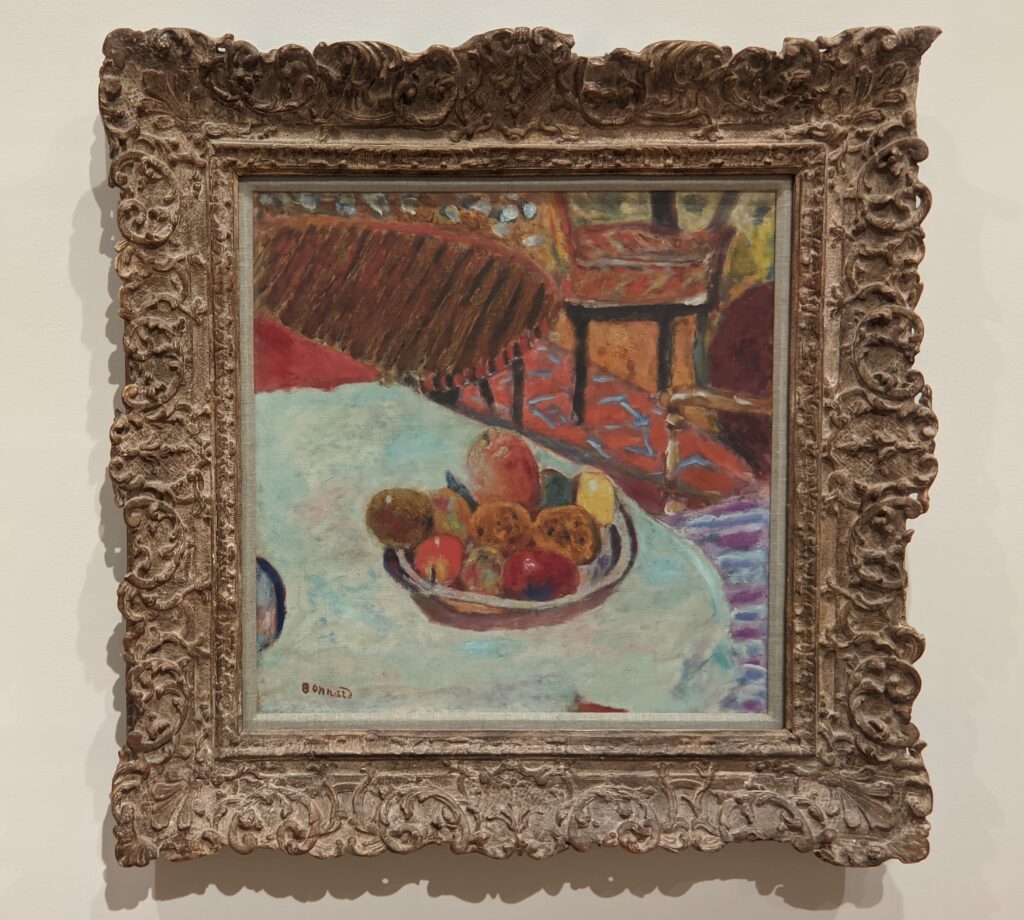

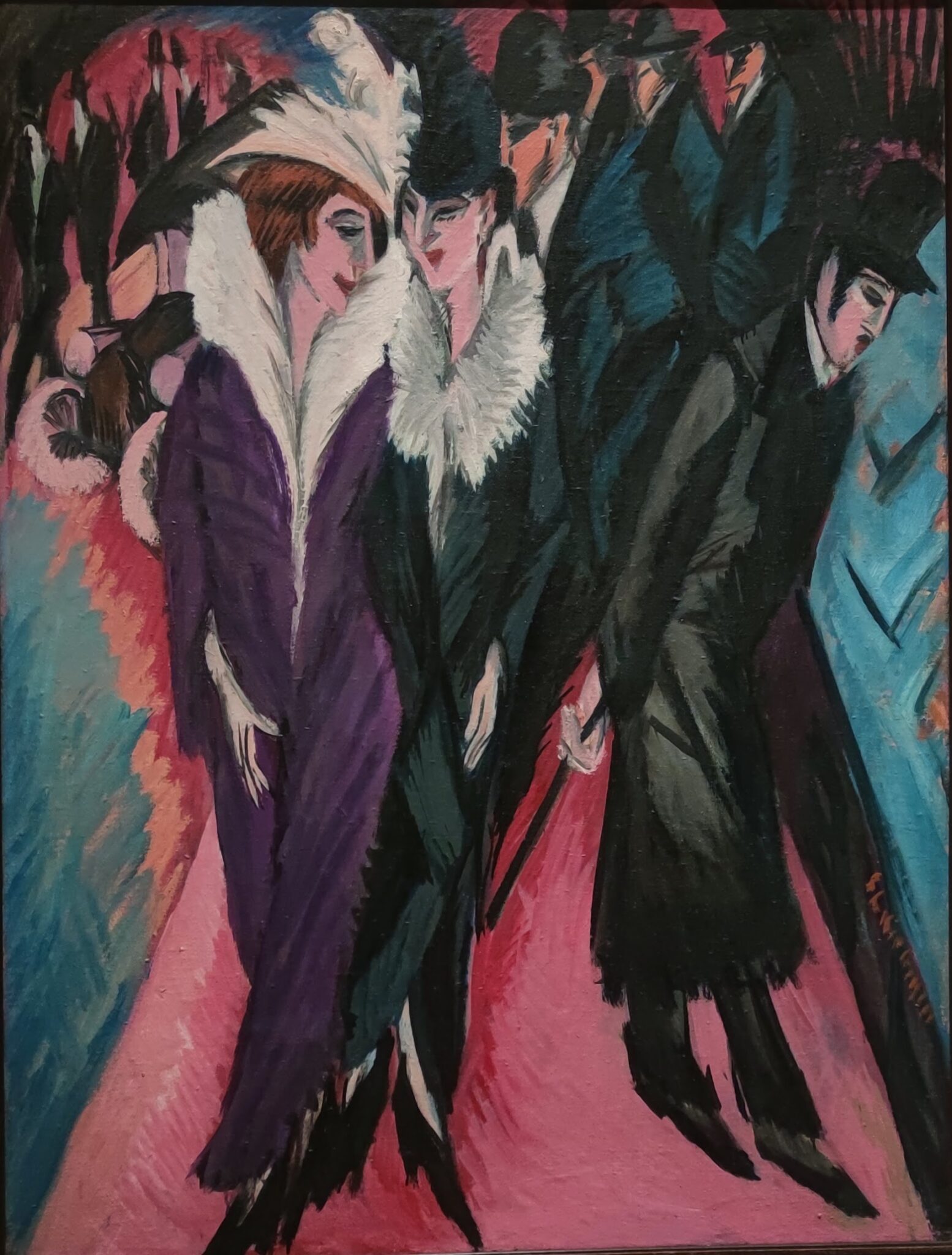

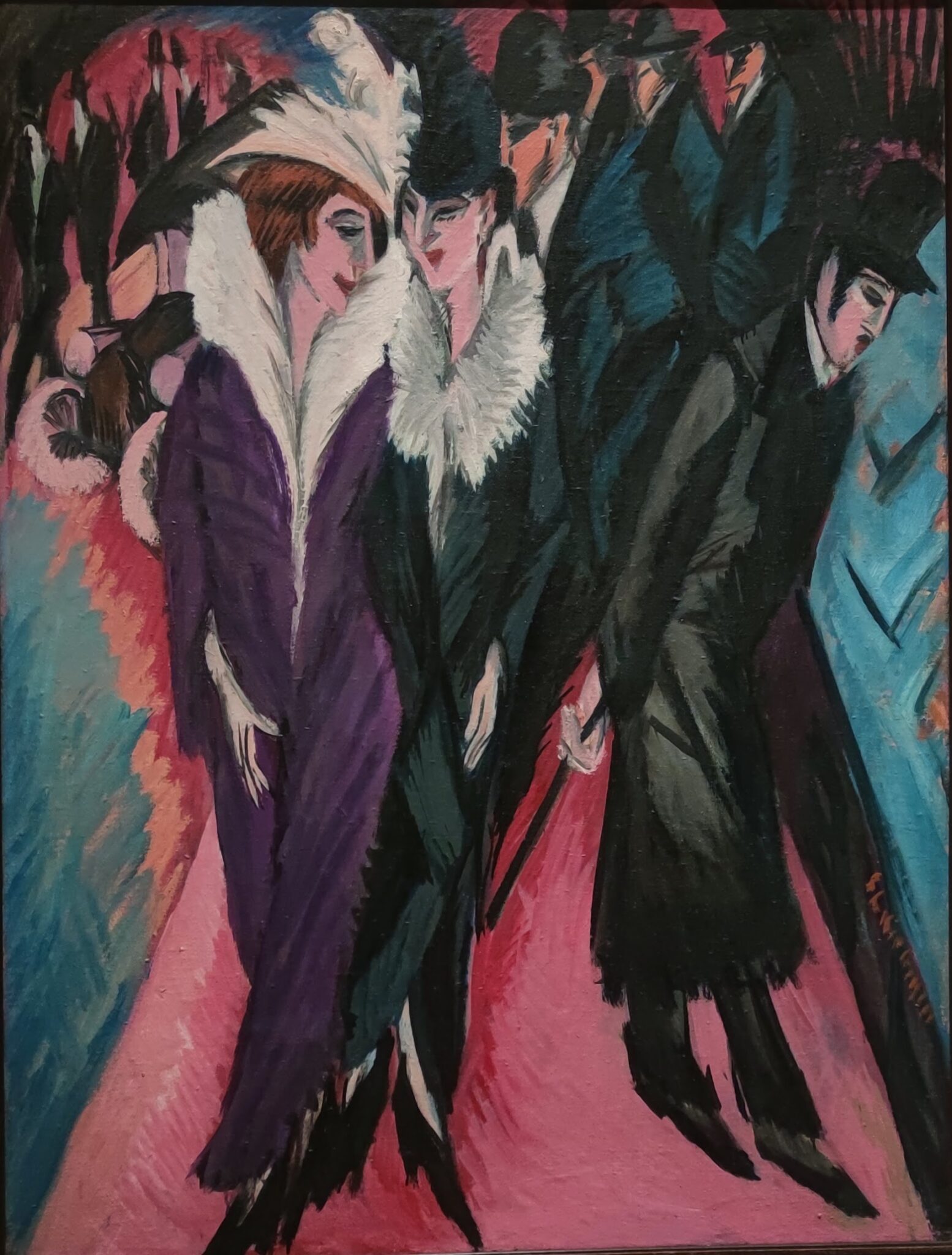

Gauguin’s oeuvre encompasses a number of influential styles. He was a leader of the Pont-Aven School, known for its bold use of color and Symbolist subject matter, and Gauguin’s art is also associated with Cloisonnism, Synthetism, and the indigenous influences and symbols from the islands of Martinique in the Caribbean and Tahiti in the Pacific. The nine weeks Gauguin and van Gogh spent together painting in Arles are famous (and infamous) in the history of art; however, Gauguin’s theory of “painting from the imagination” was ill-suited for van Gogh, who drew inspiration chiefly from nature. Gauguin inspired Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso and the great artists known as the Nabis group, including Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Felix Vallotton and Maurice Denis; whereas, the legacy of Vincent van Gogh profoundly affected German and Austrian modernism, and inspired Expressionism around the world.

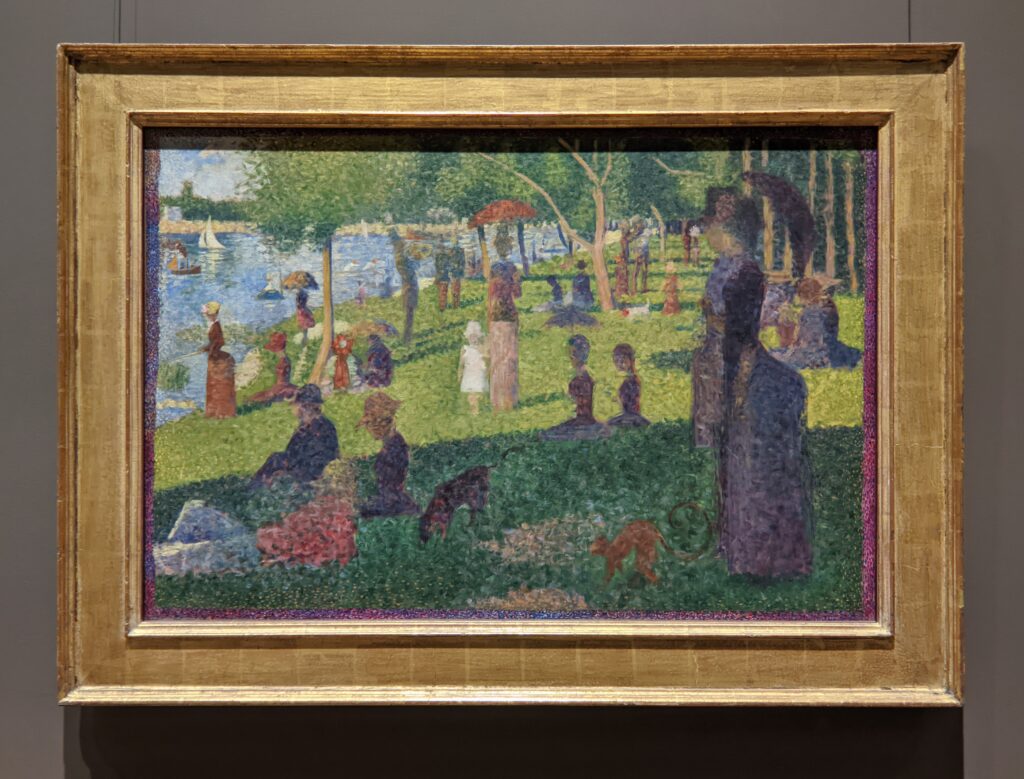

Art Lovers’ TIP: If you want to see the large-scale oil painting “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte” by Seurat, and learn about the Van Gogh exhibition which was on view at the Art Institute of Chicago during the summer of 2023, please read our article entitled “Chicago — See the Most Extraordinary Art & Architecture in the USA.”

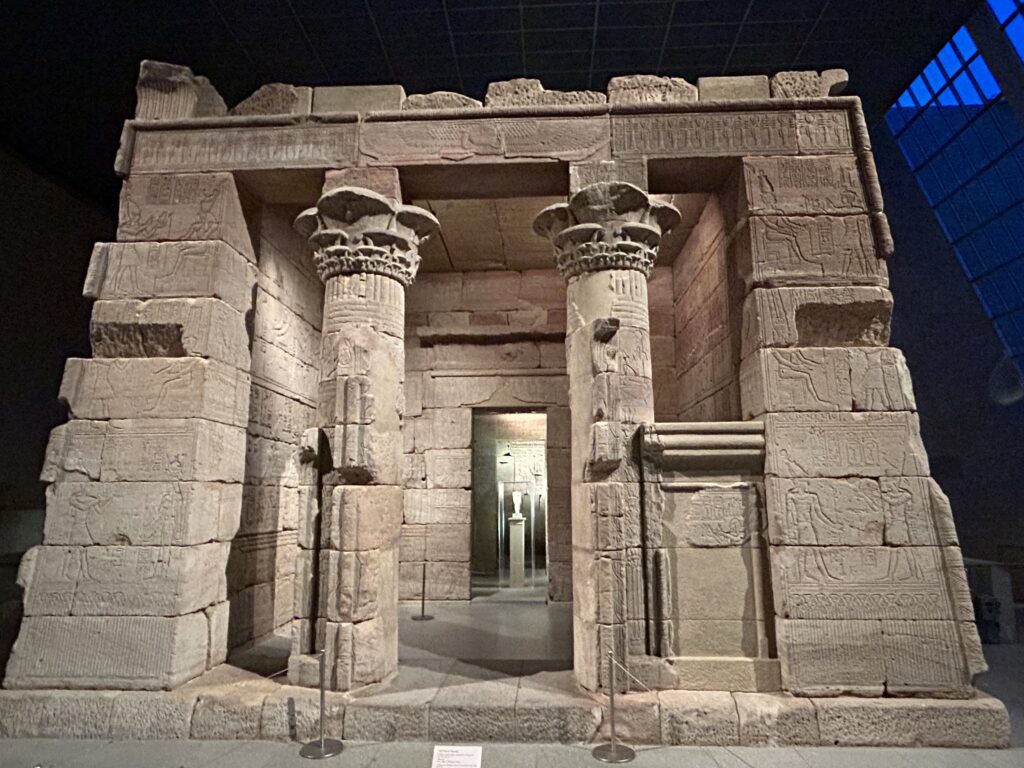

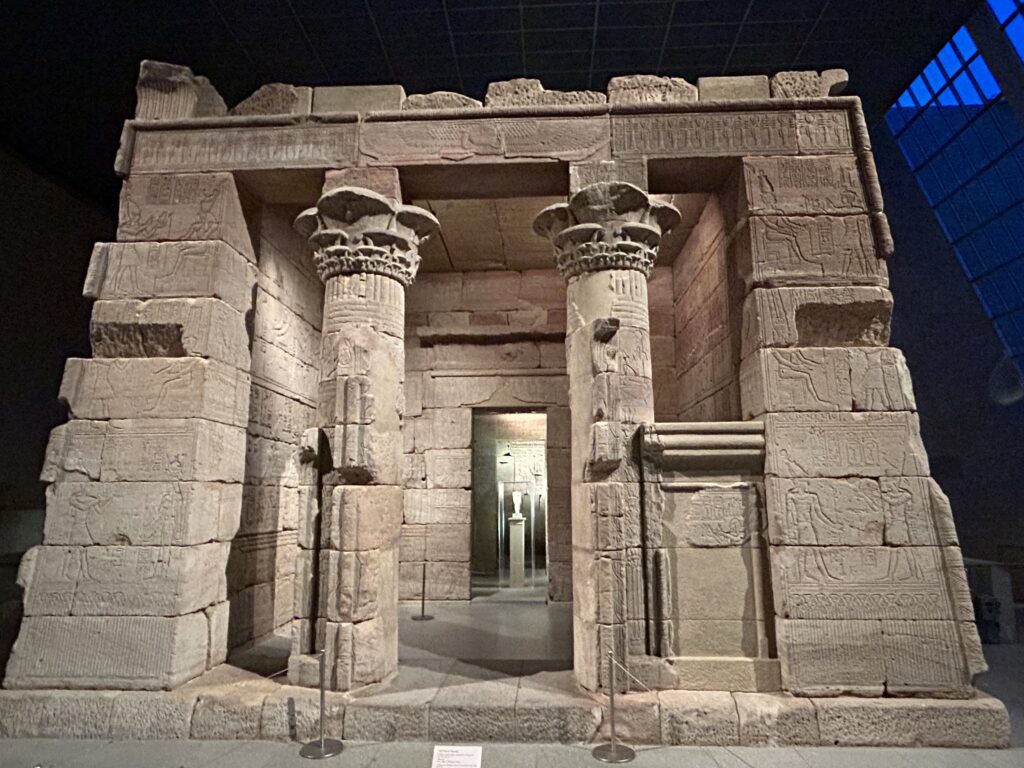

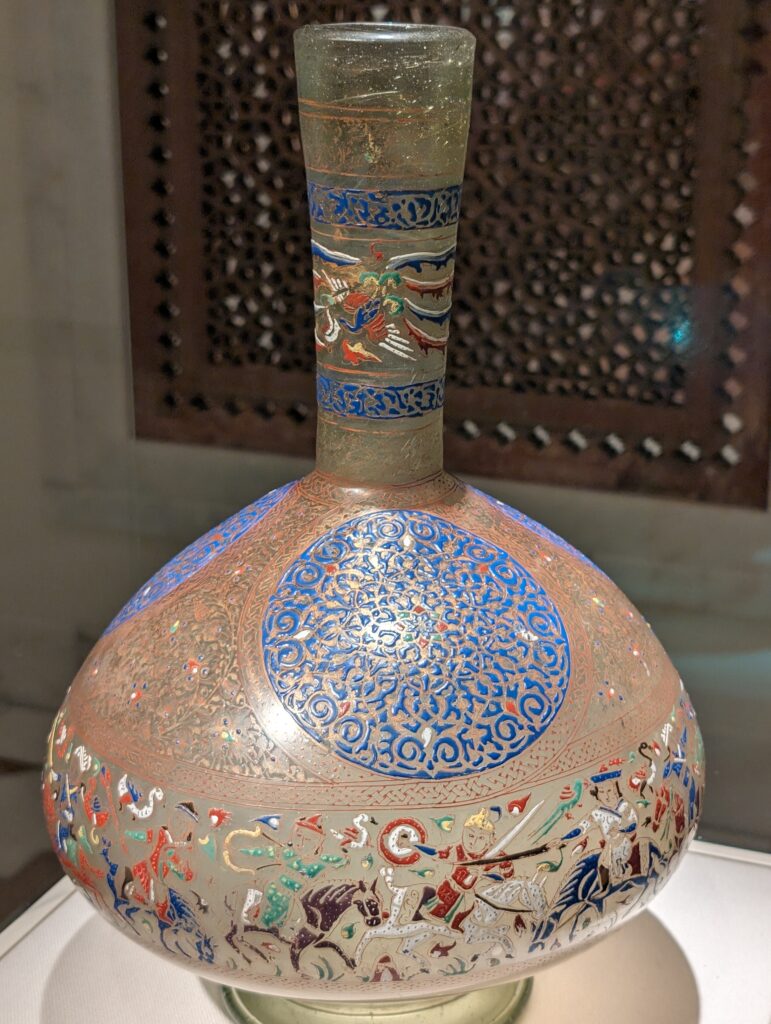

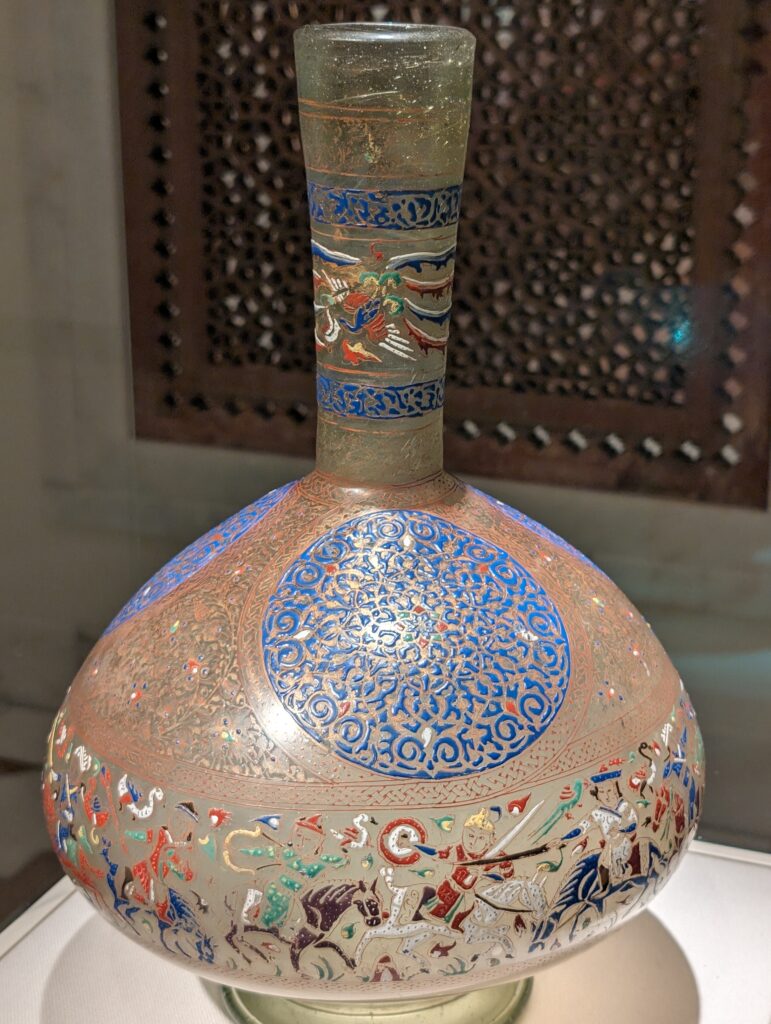

After you take in the wonderfully broad interpretation of European Post-Impressionism at the Met, perhaps you will venture into the lovely American Wing, the impressive Egyptian and Asian galleries, the rooms devoted to modern American art after 1950, or the exceptional Michael Rockefeller Wing’s collection of arts from Africa, Oceania & the Americas. The Period Rooms from Europe and the Costume Institute are also noteworthy.

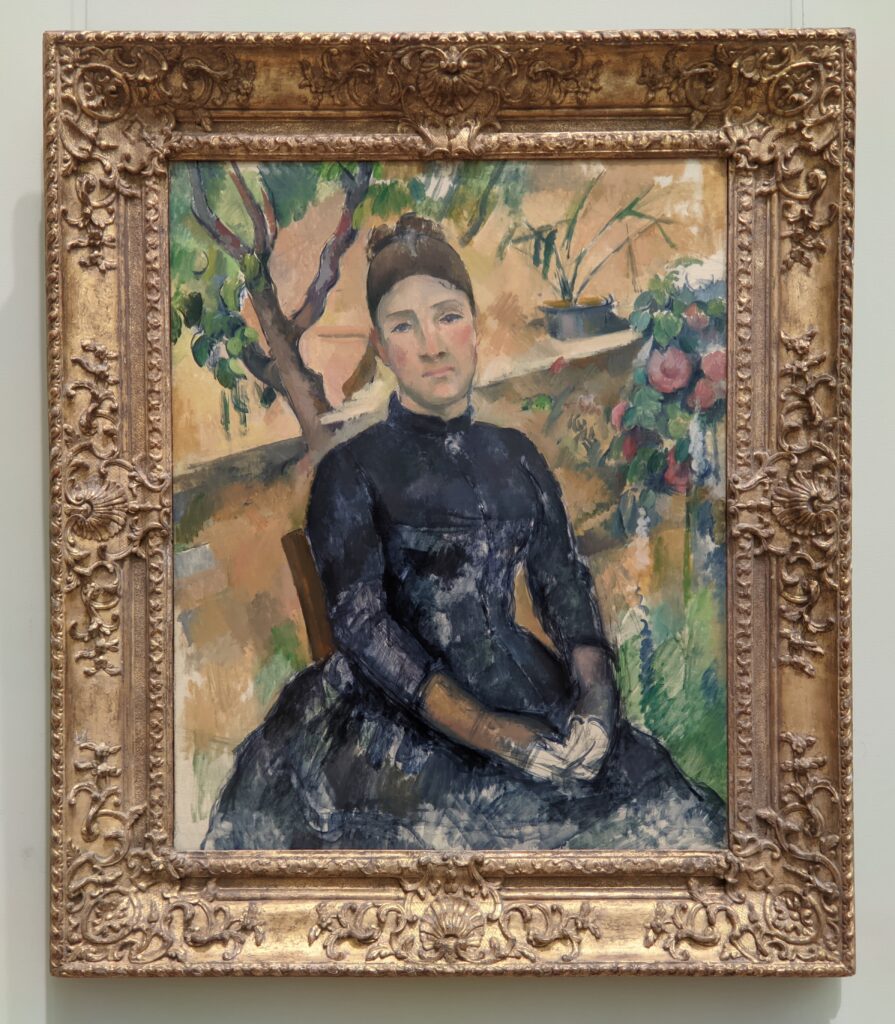

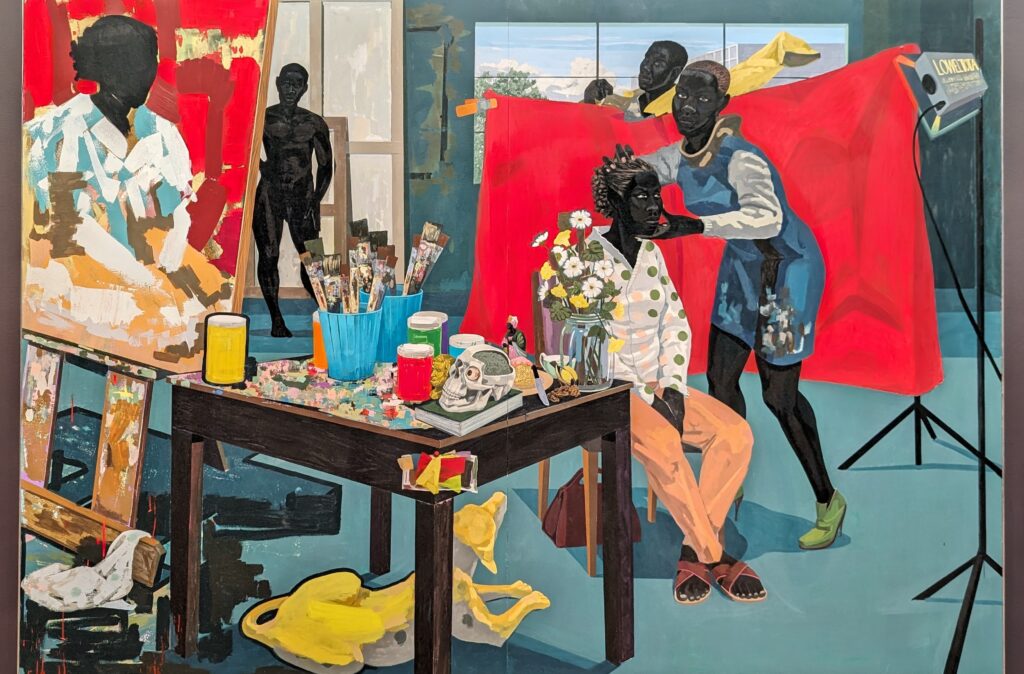

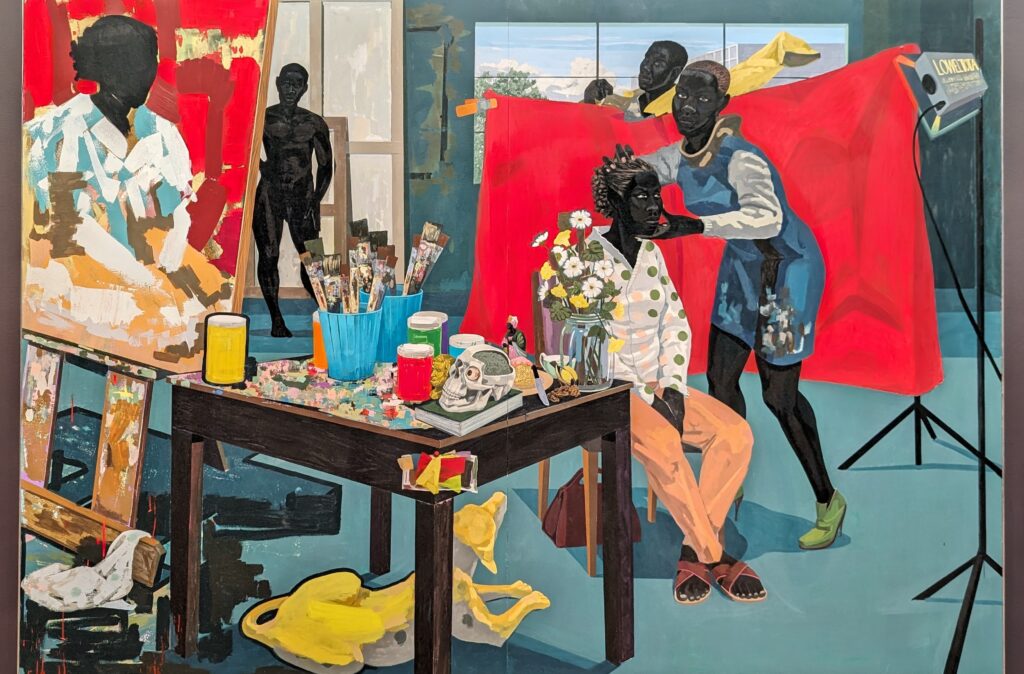

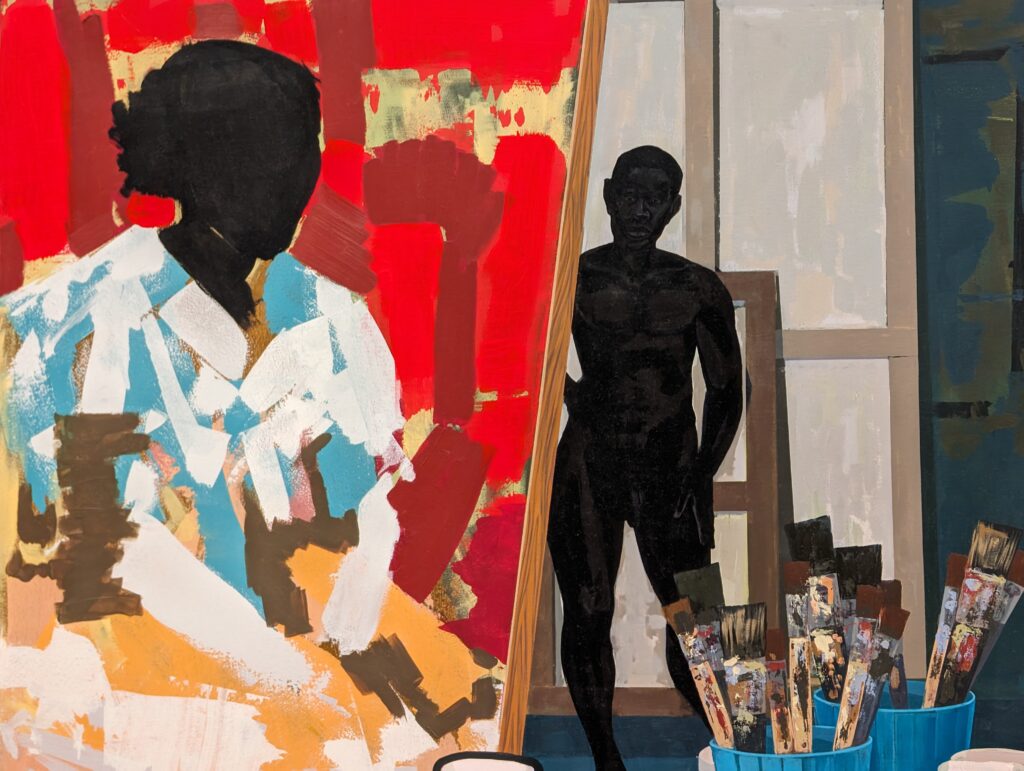

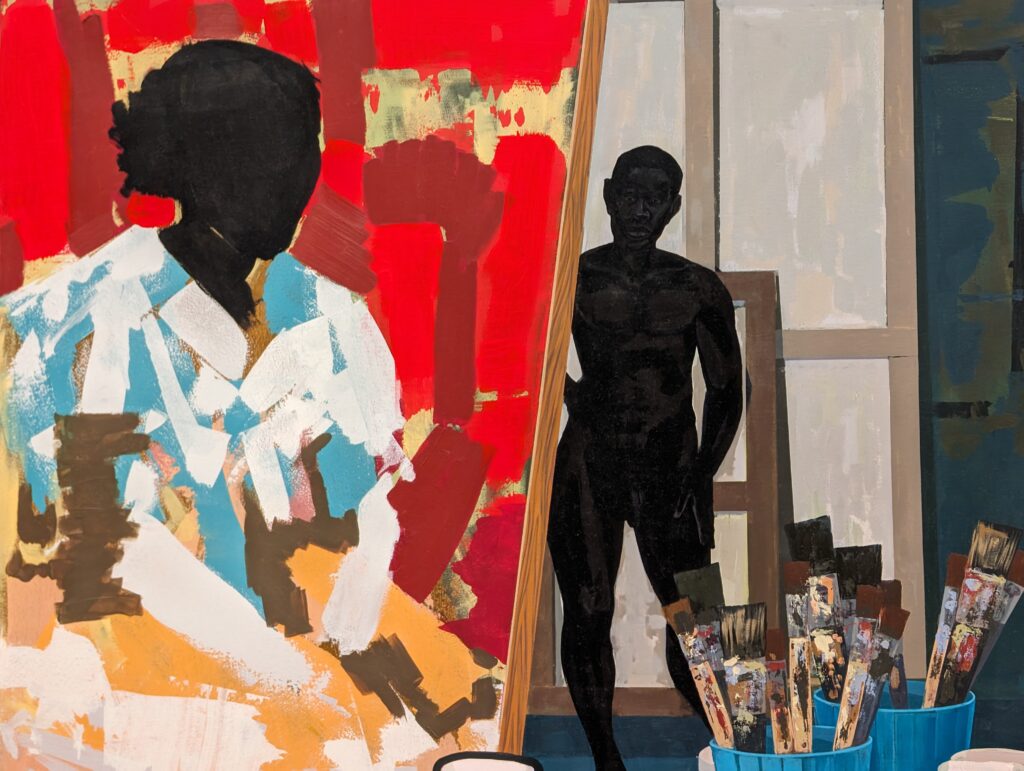

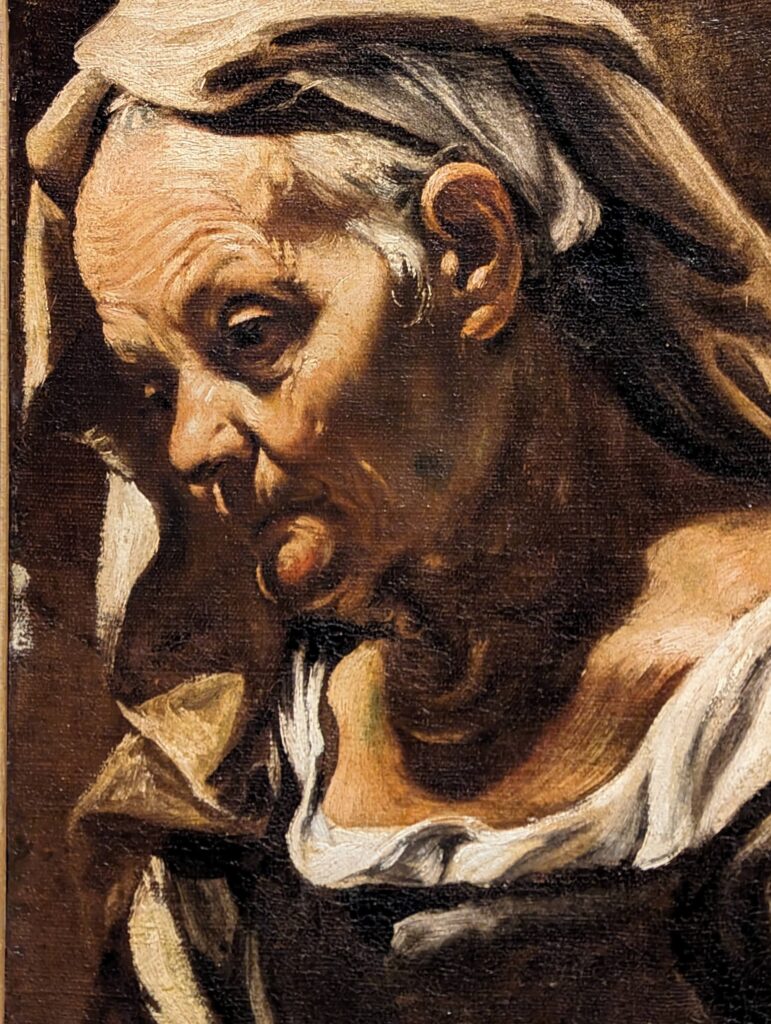

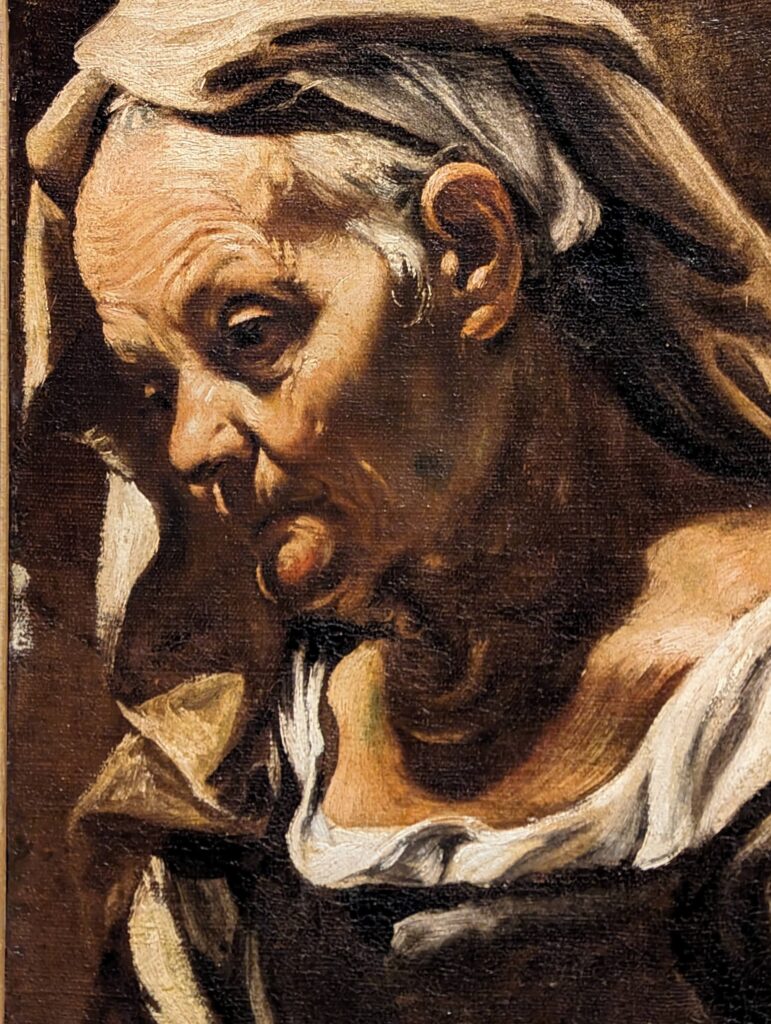

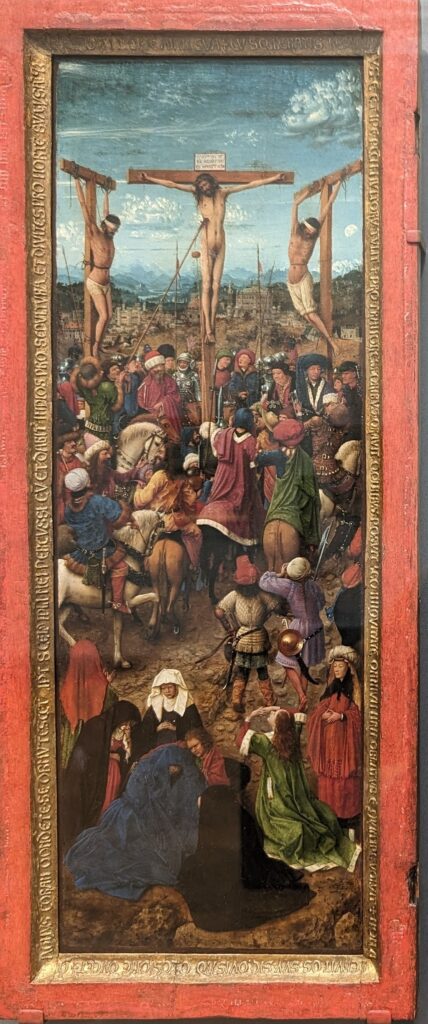

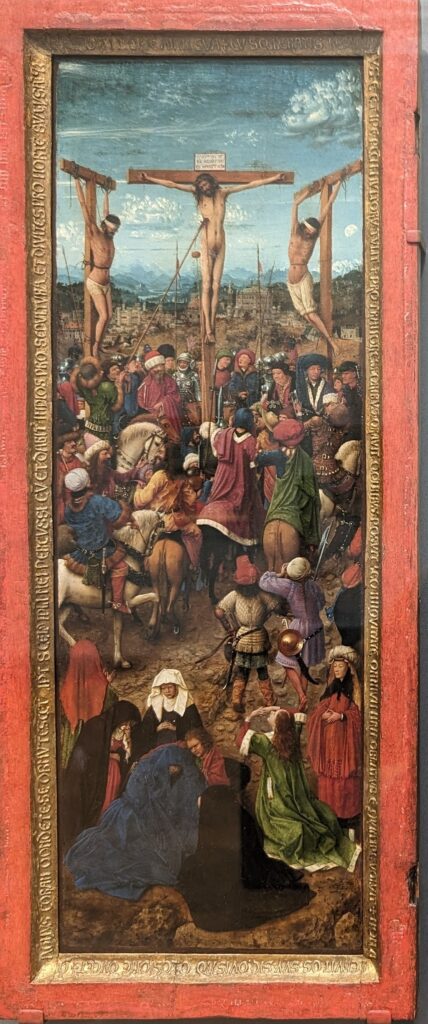

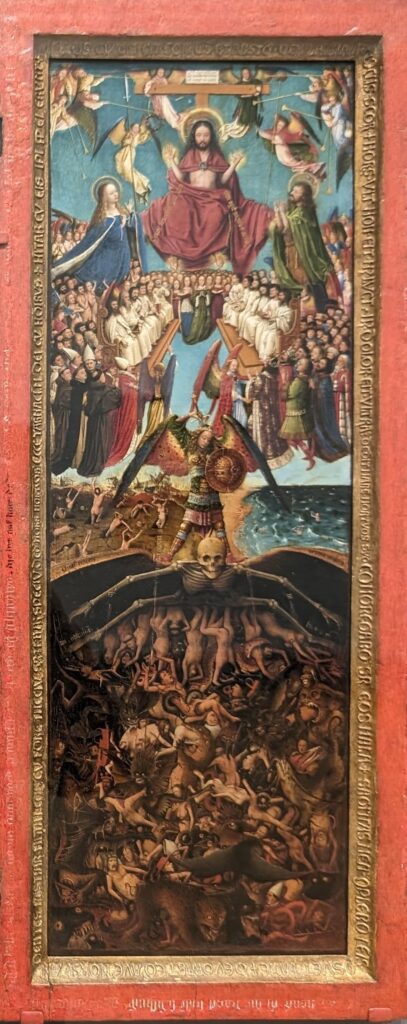

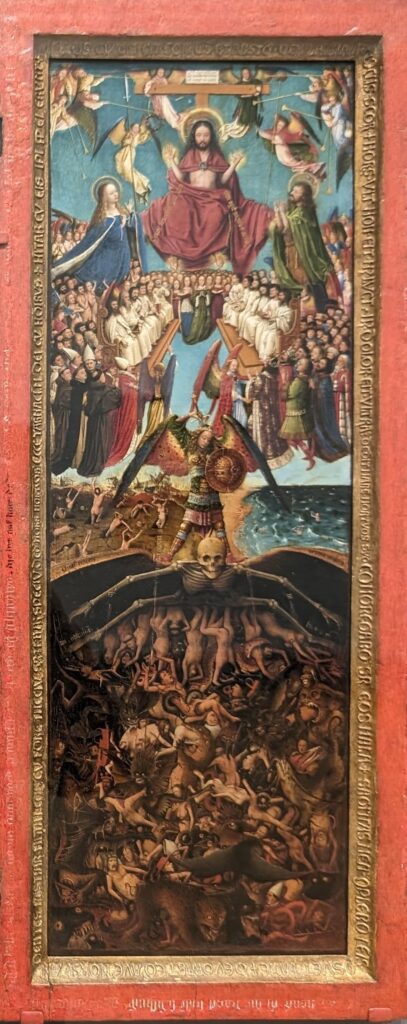

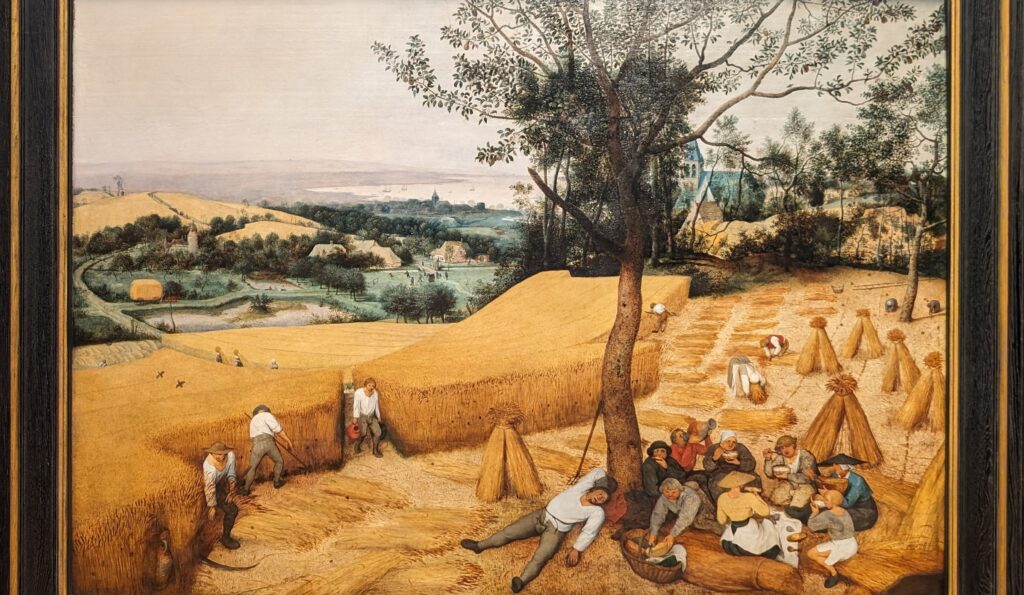

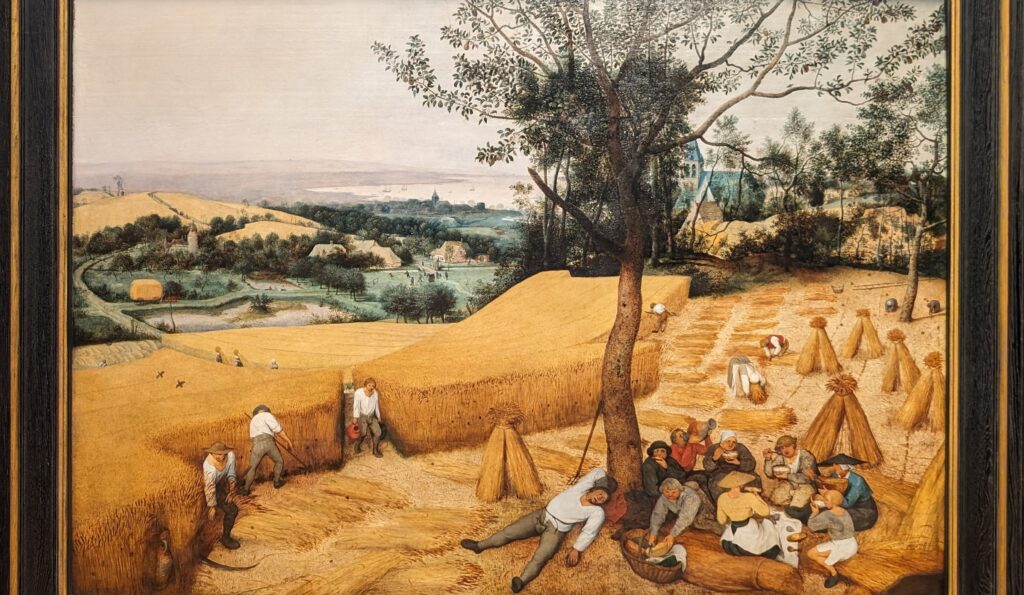

European Paintings 1300 — 1800

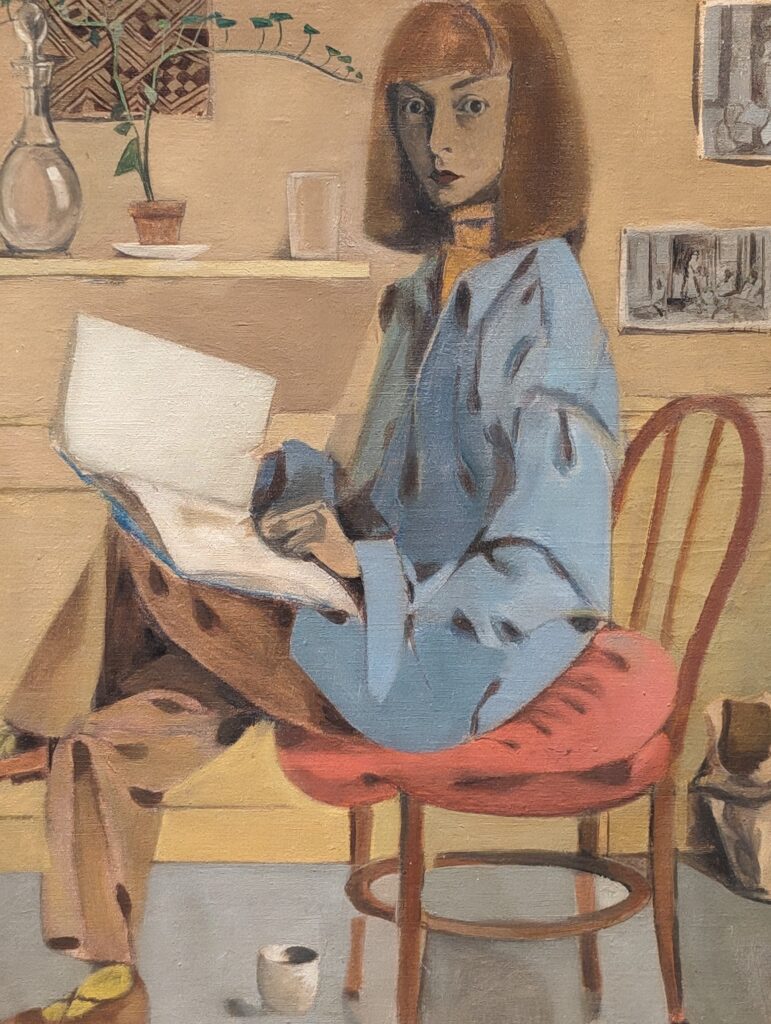

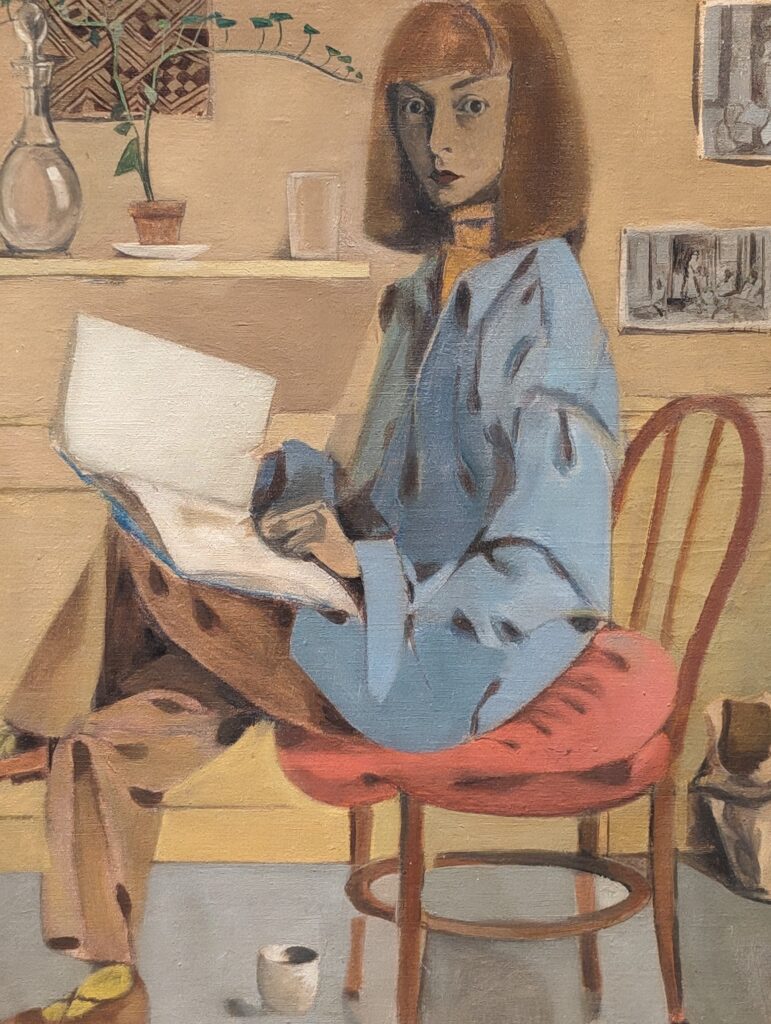

45 galleries devoted to European Paintings have reopened after a 5-year renovation, which added new skylights above the chronological display of over 700 works of art created between 1300 and 1800. The re-installation at the top of the Great Hall staircase with much improved quality of light enhances our appreciation of the largest collection of 17th-century Dutch art in the Western Hemisphere, as well as the most outstanding holdings of El Greco and Goya outside Spain, and includes some surprising, innovative pairings with paintings by Cézanne, Elaine de Kooning, Picasso, Beckmann and Kerry James Marshall, among others.

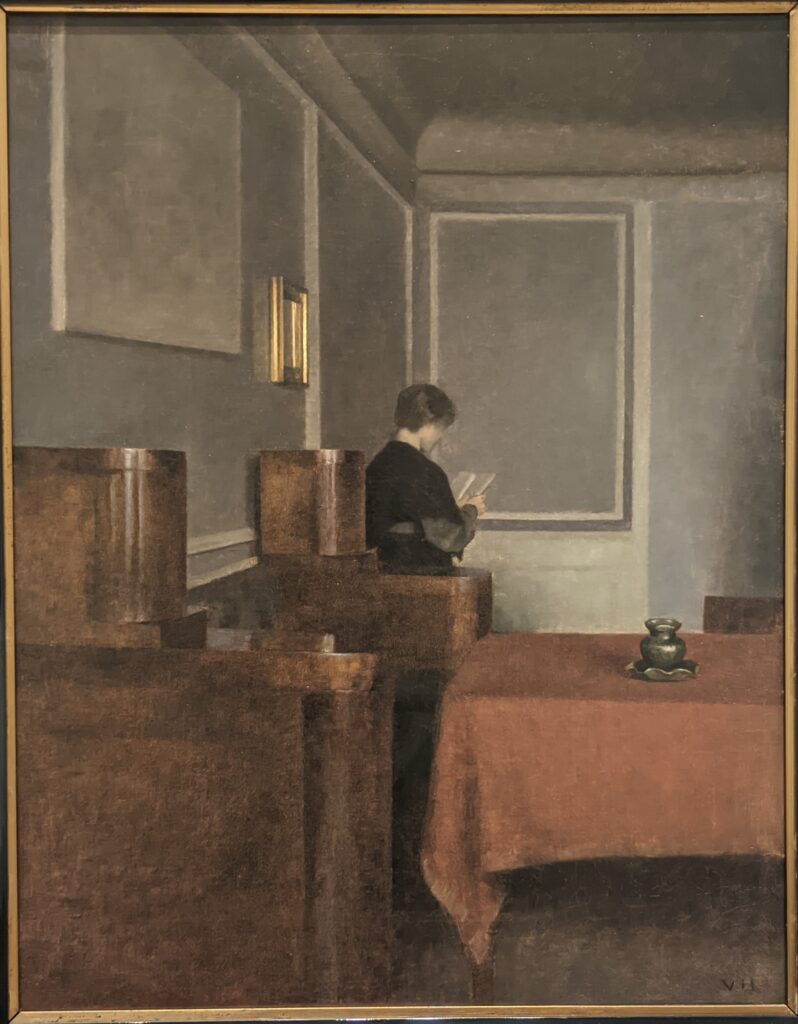

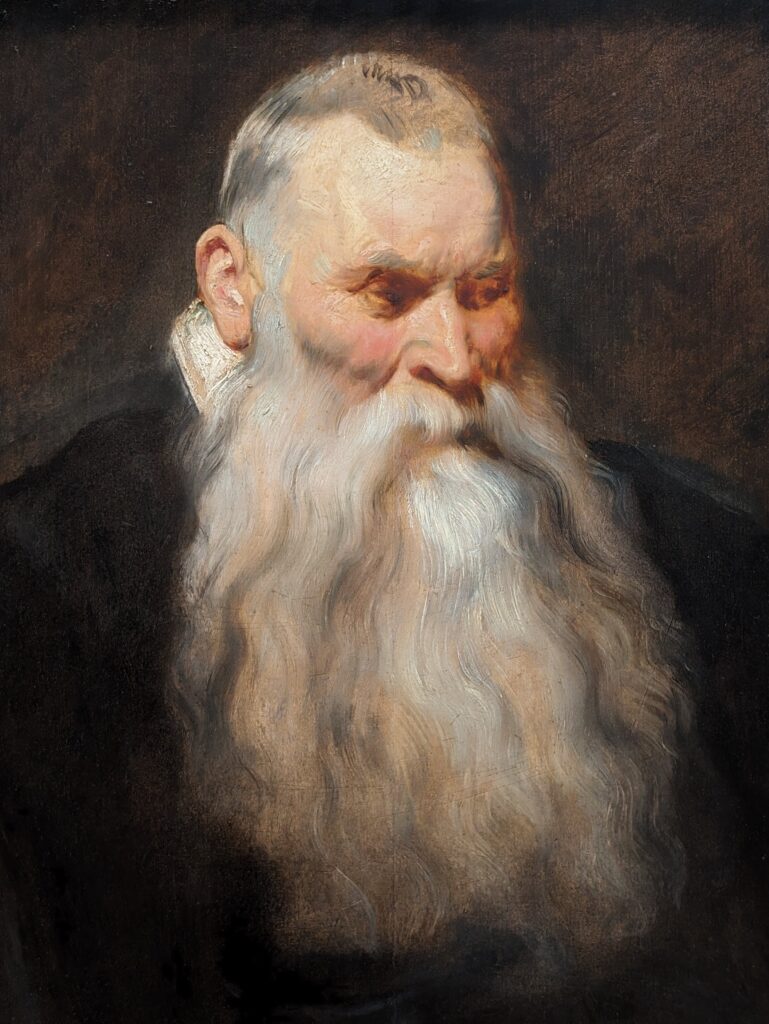

Dutch Masterpieces at the Met

The Met possesses unusually strong holdings of Netherlandish painting, and you can enjoy its comprehensive holdings of canvases by Rembrandt and Vermeer, among many other fine painters.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606 — 69)

Johannes Vermeer (1632 — 75)

Exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Met is closed on Wednesdays. Entry to special exhibitions on view at the Met Museum are included with the price of admission.

Through September 2, 2024, the Metropolitan Museum of Art is presenting “SLEEPING BEAUTIES: Reawakening Fashion,” featuring over 200 garments spanning four centuries.

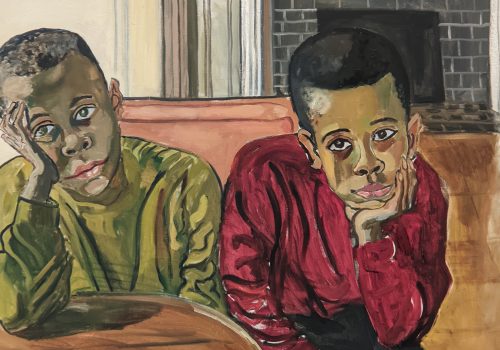

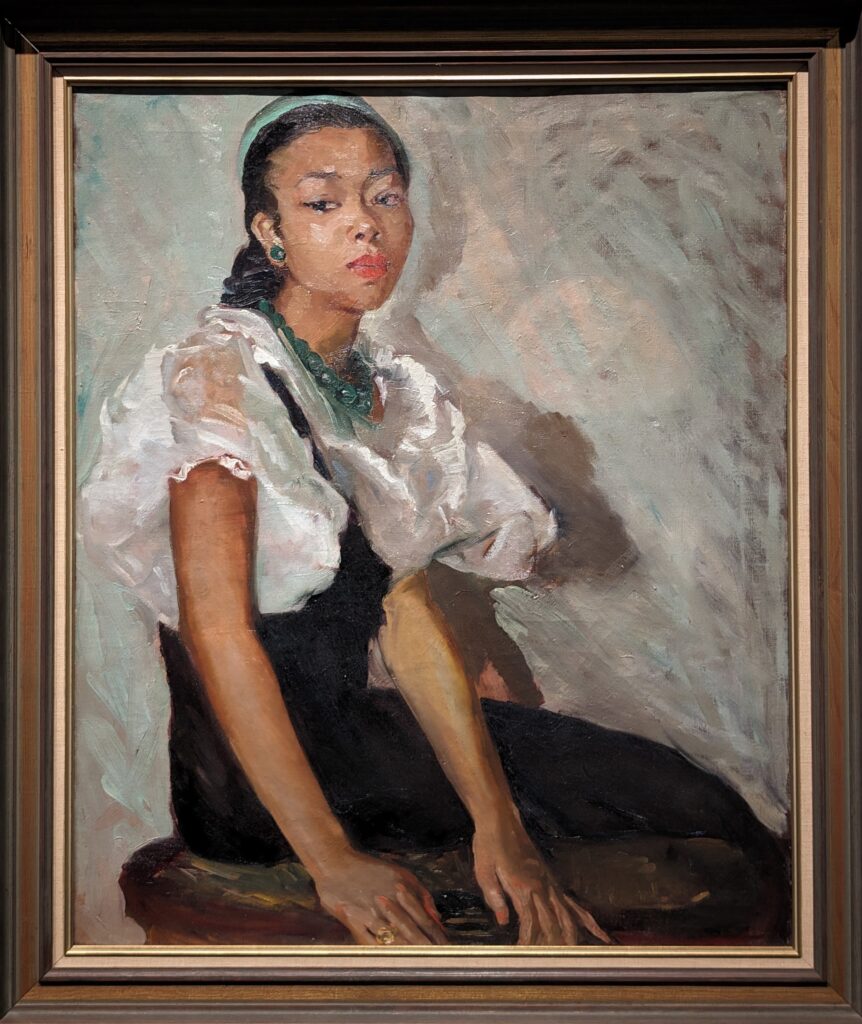

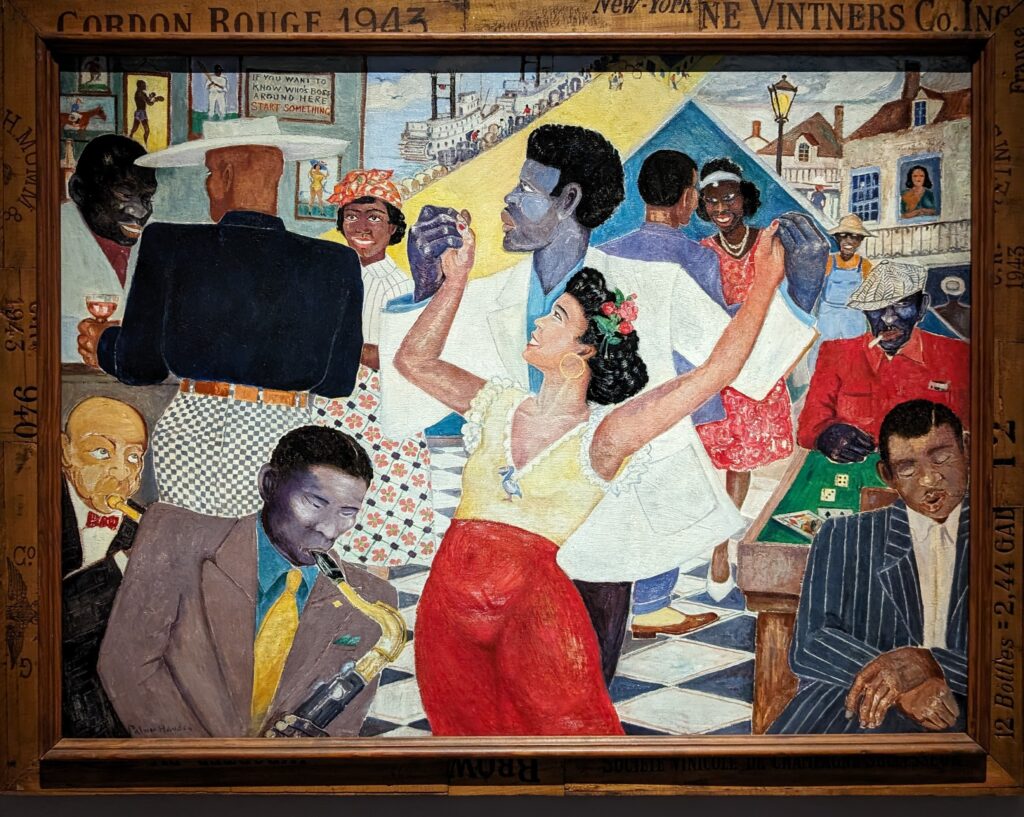

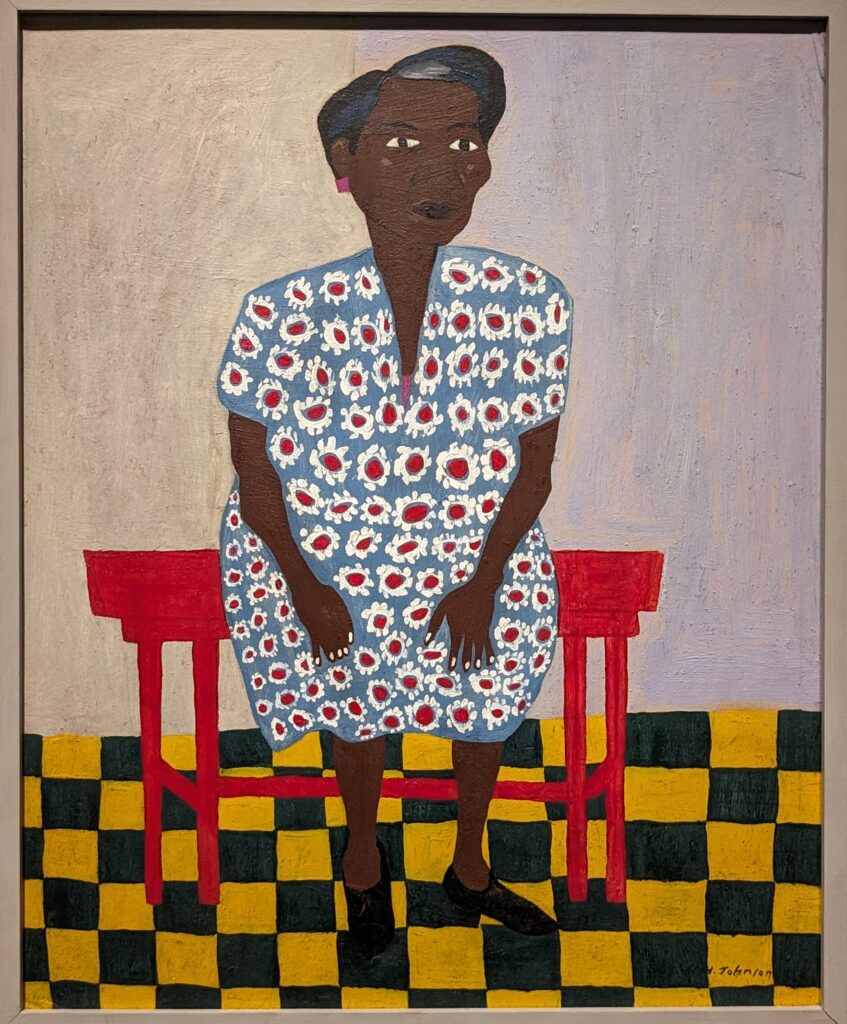

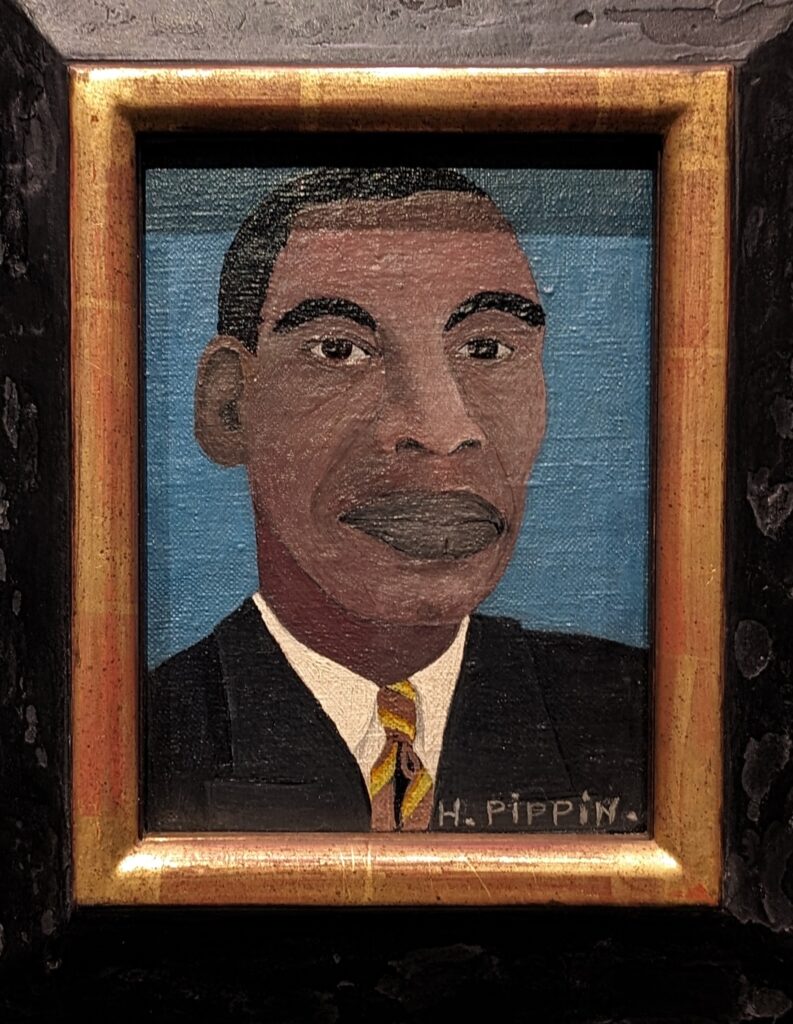

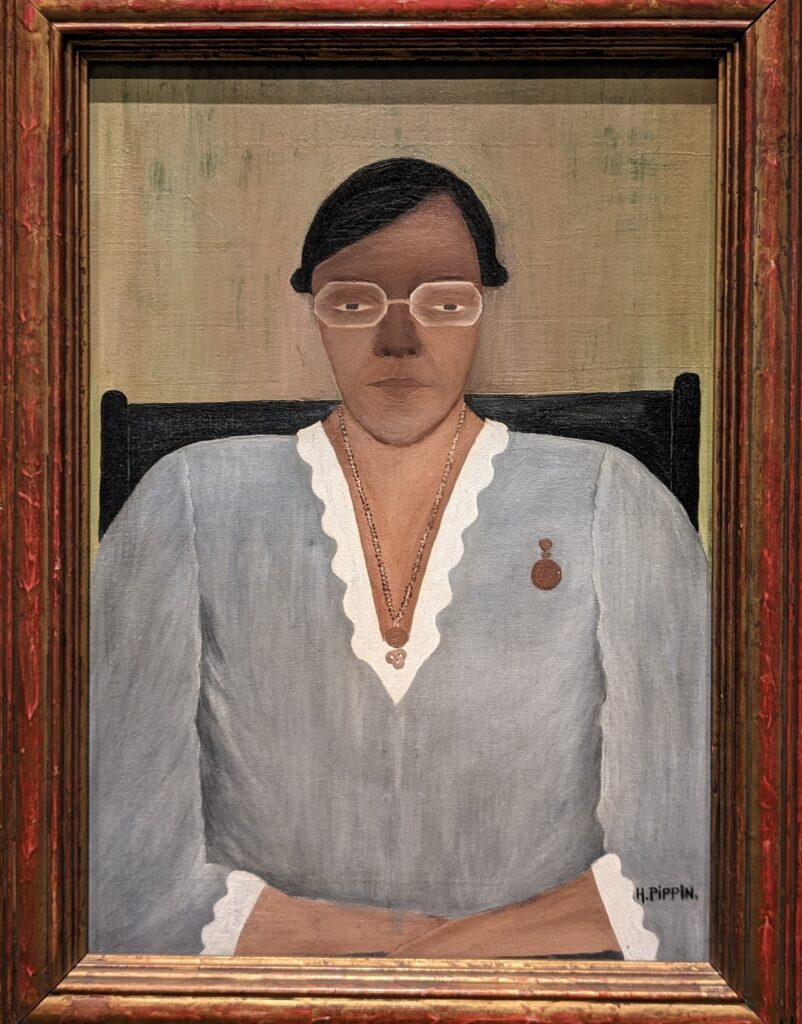

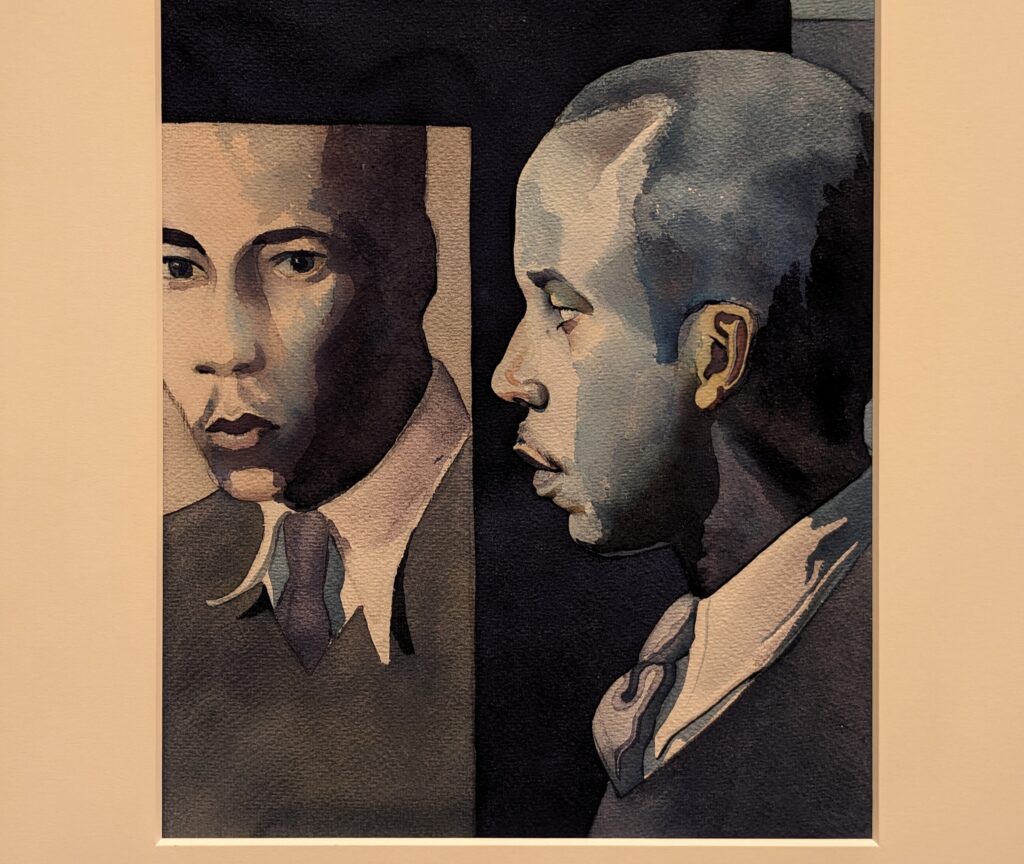

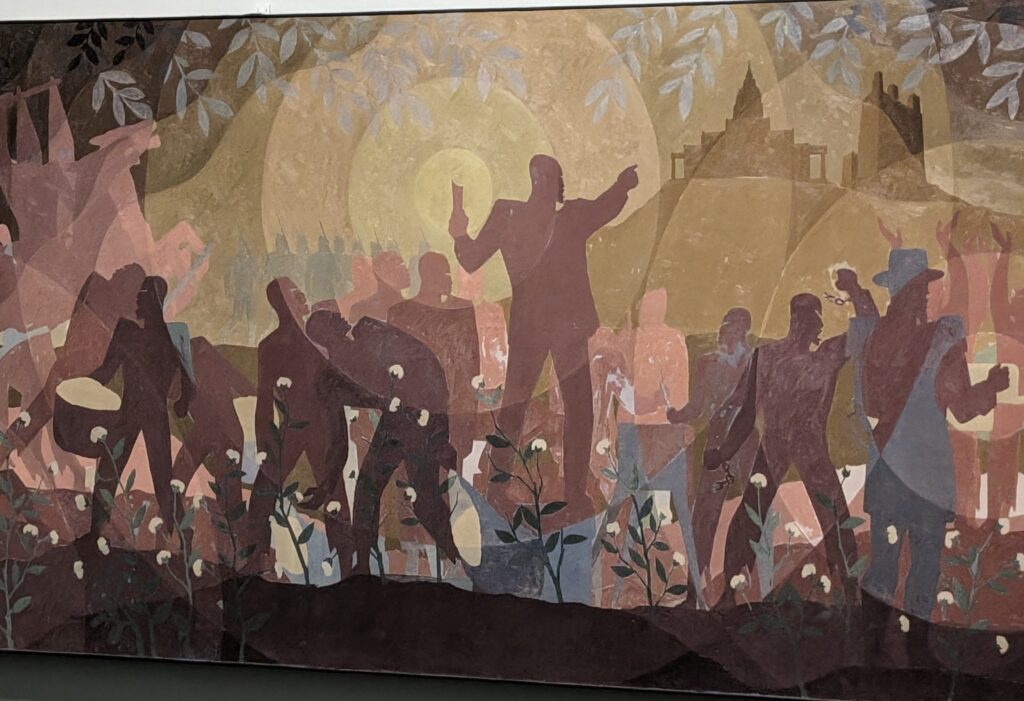

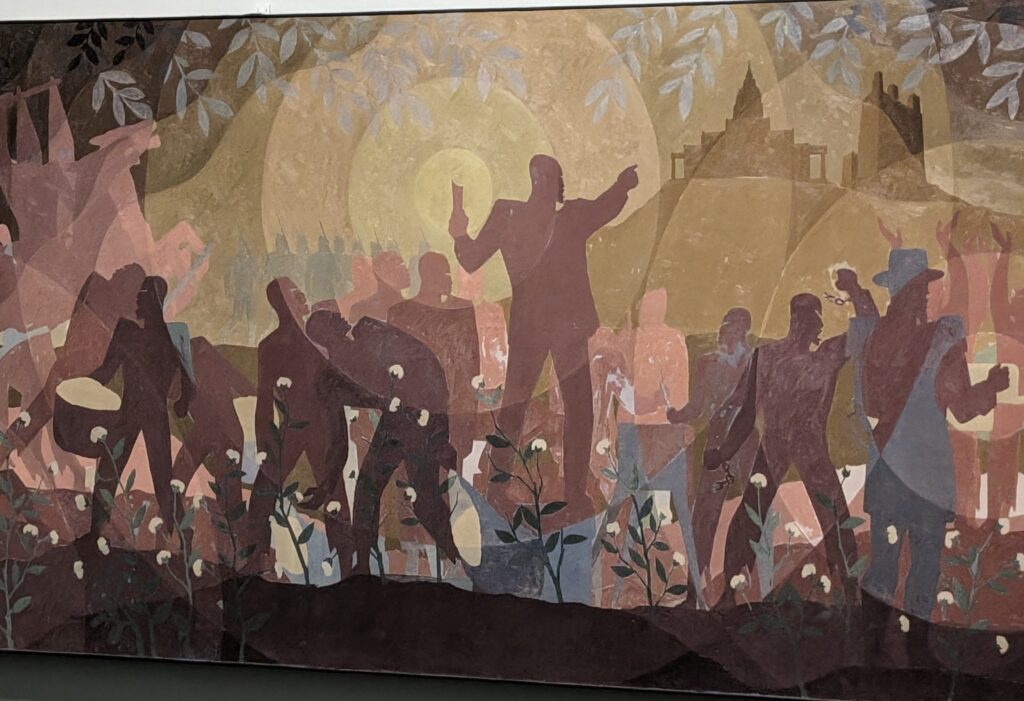

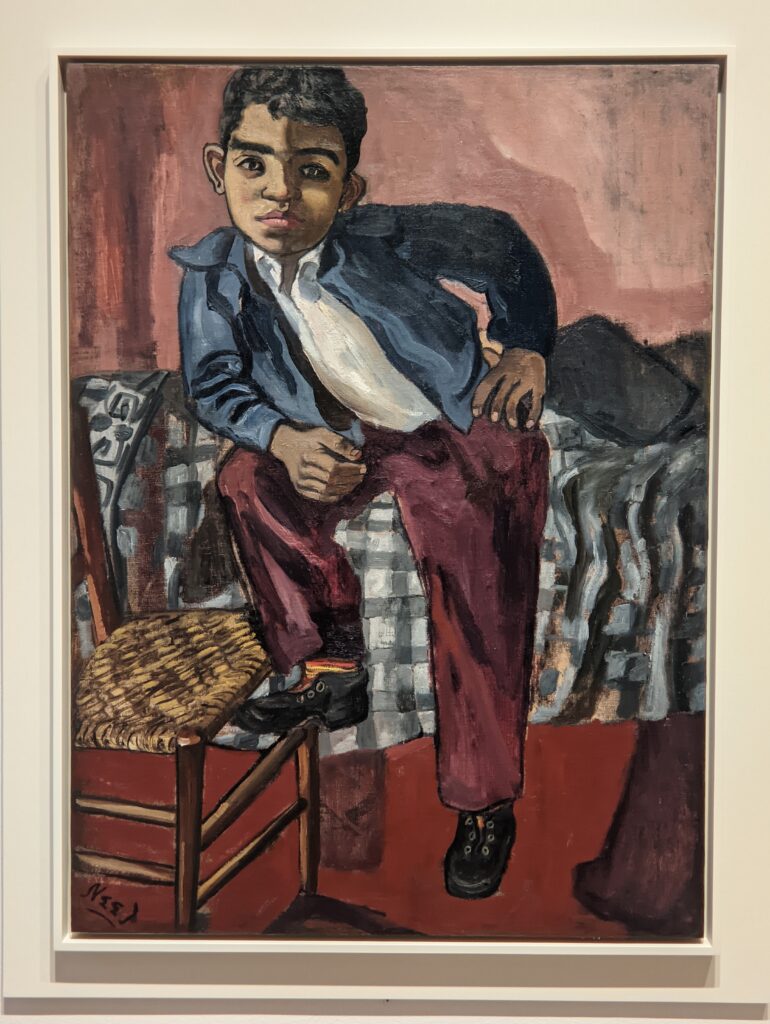

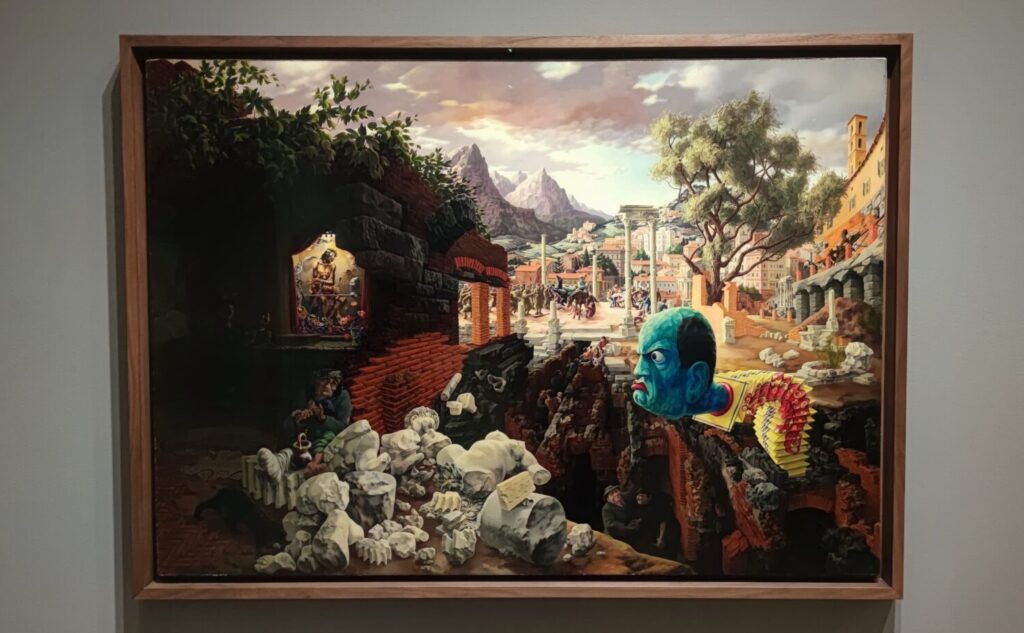

The current show entitled THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE — on view through July 28, 2024 — contrasts the depiction of Black life by artists working in Harlem beginning in the 1920s with the portrayal of the international African diaspora by their European counterparts.

Previous Special Exhibitions

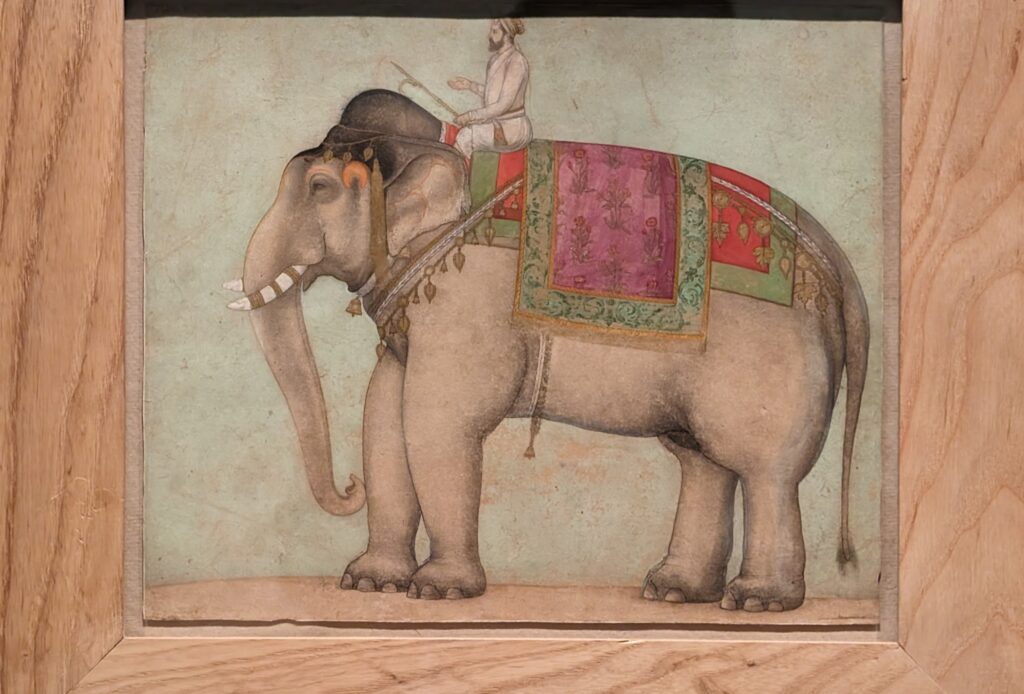

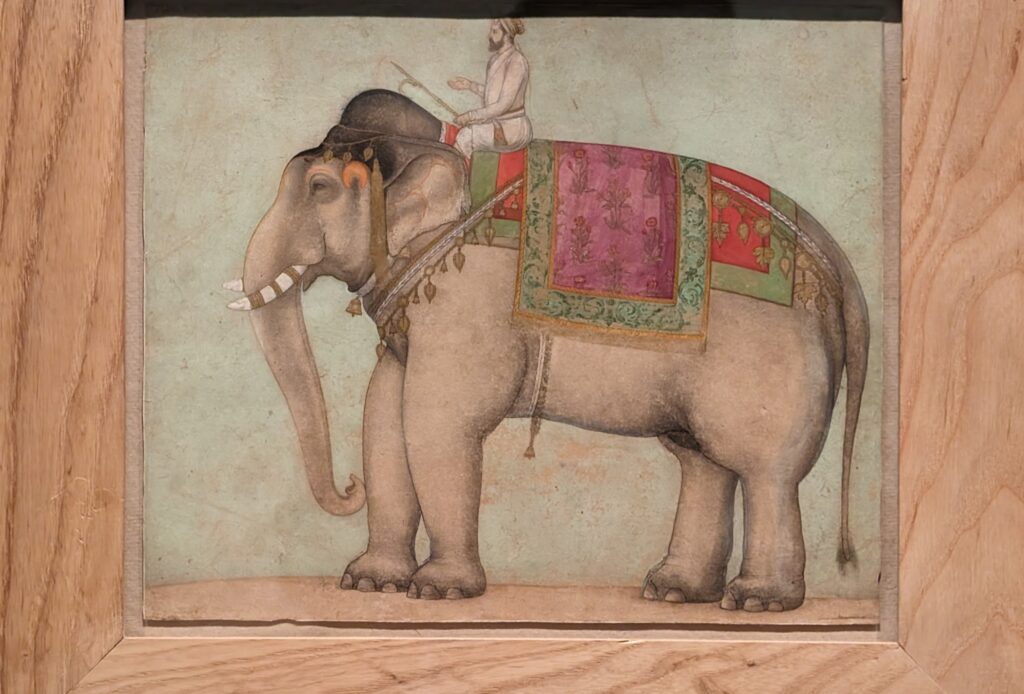

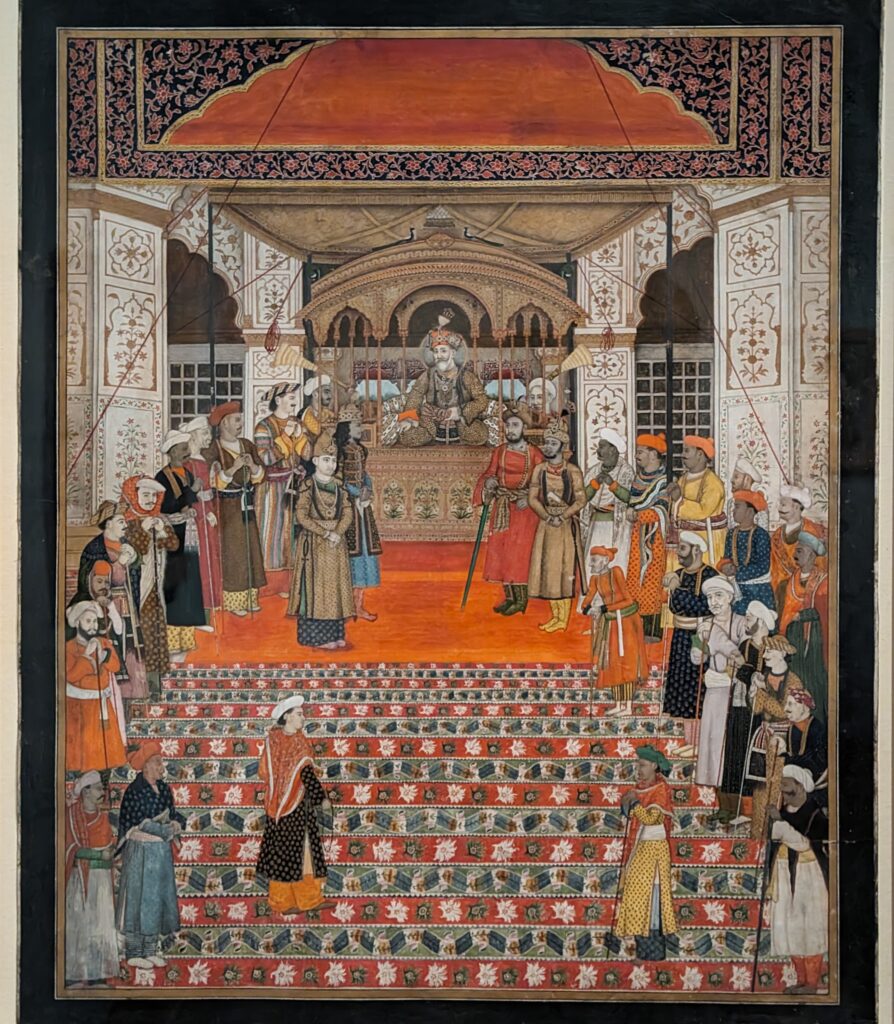

INDIAN SKIES, Hodgkin’s Collection of Indian Court Paintings from the Mughal, Deccani, Rajput & Pahari Courts, Closed June 9, 2024

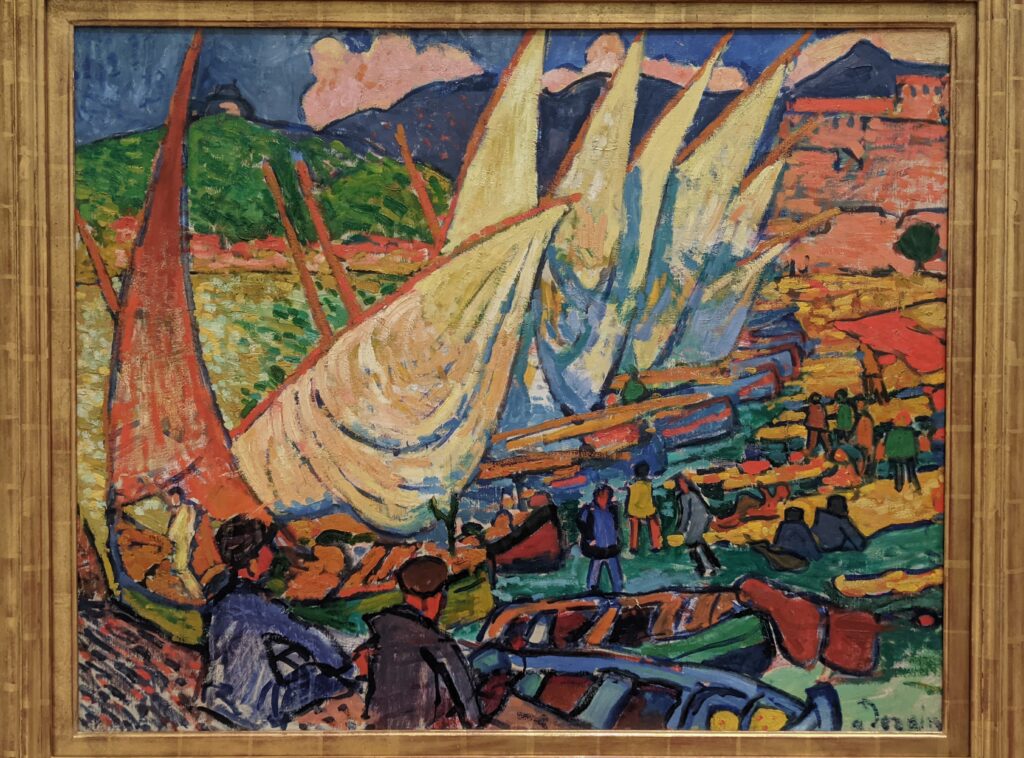

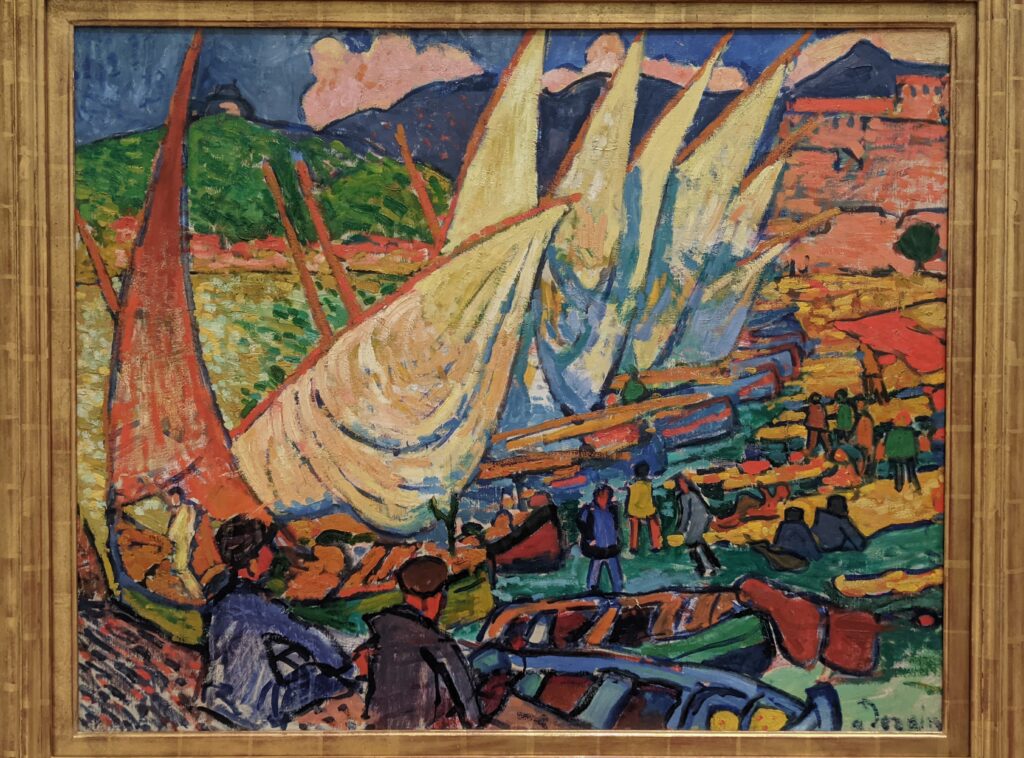

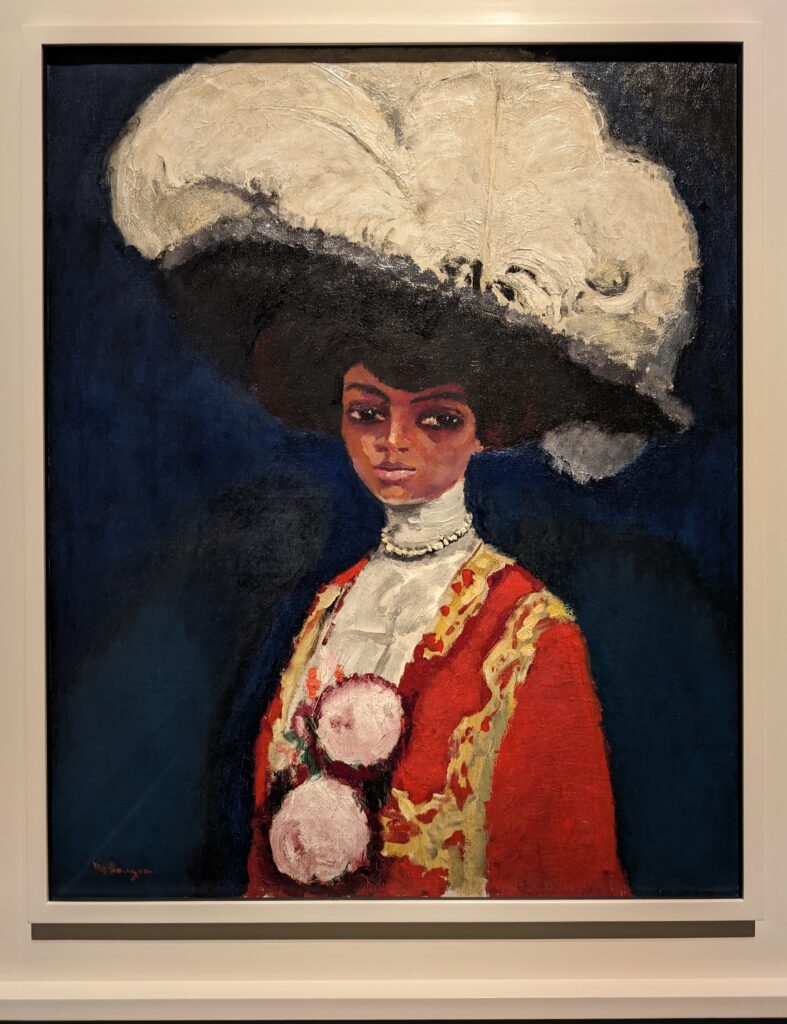

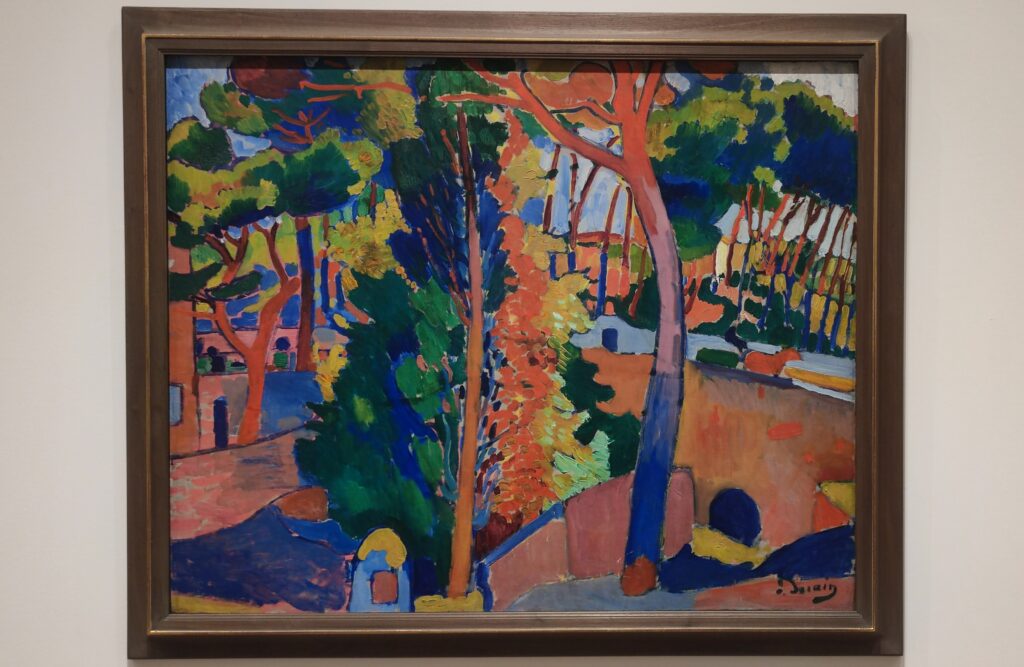

For additional images from current and past exhibitions at the Met, please read our article “New York City — Fashionable Exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum,” where you’ll see garments from the Met’s blockbuster exhibit “KARL LAGERFELD — A Line of Beauty” (held in the spring of 2023) and one painted by Andre Derain (below).

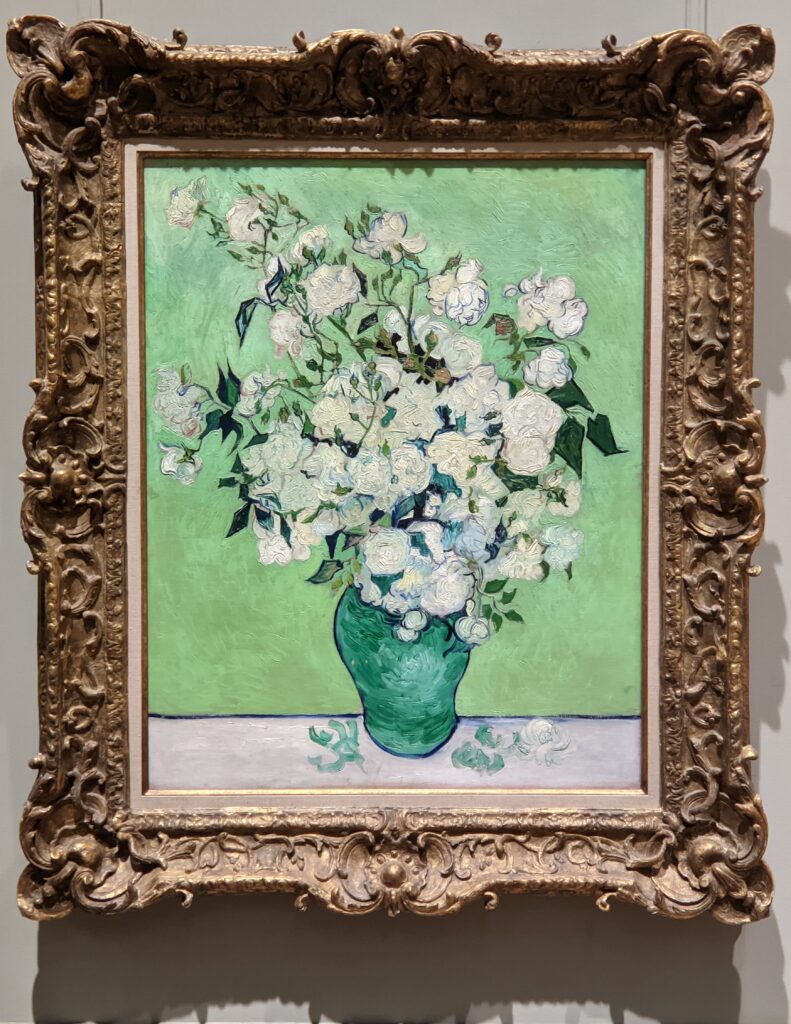

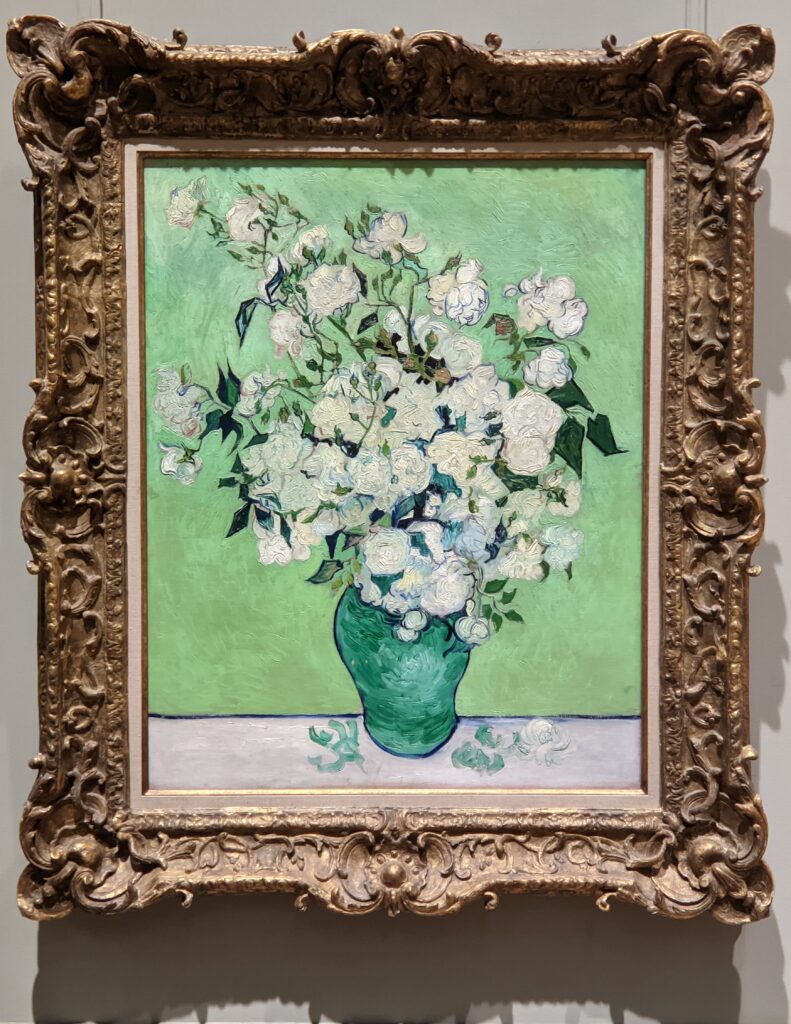

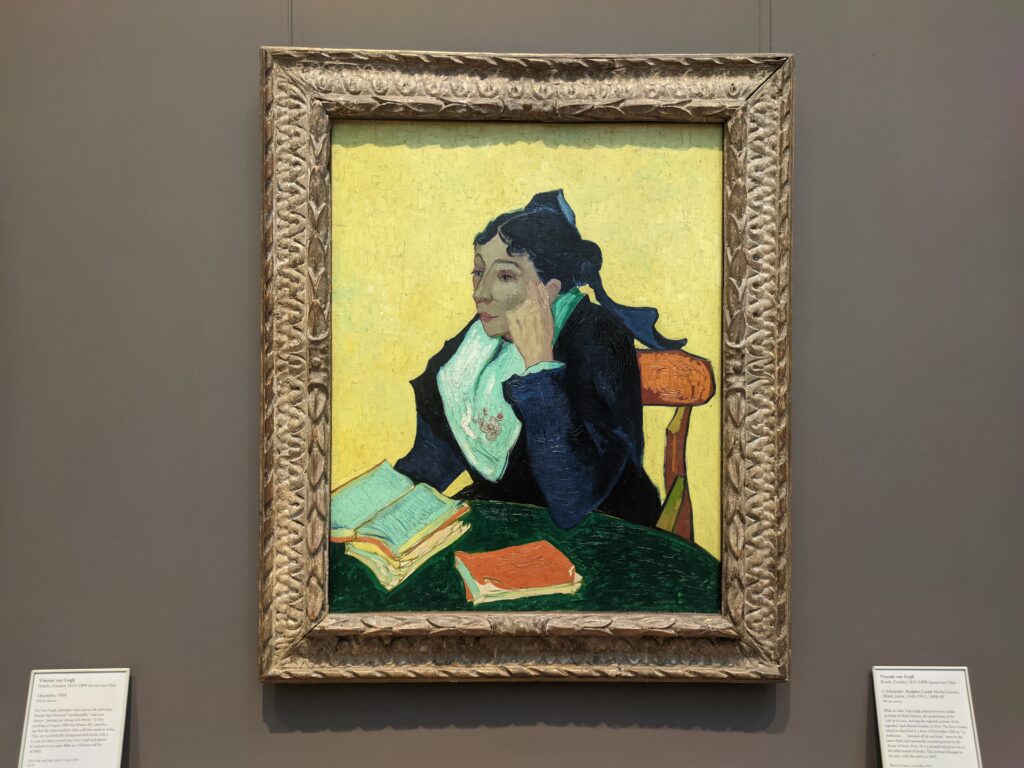

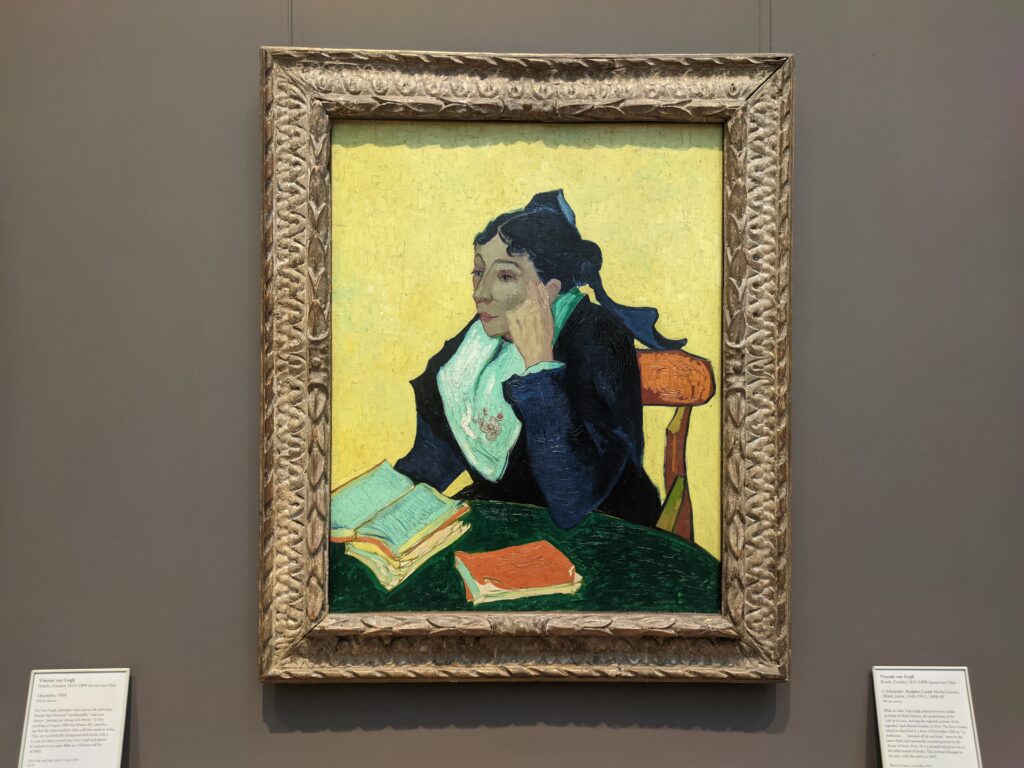

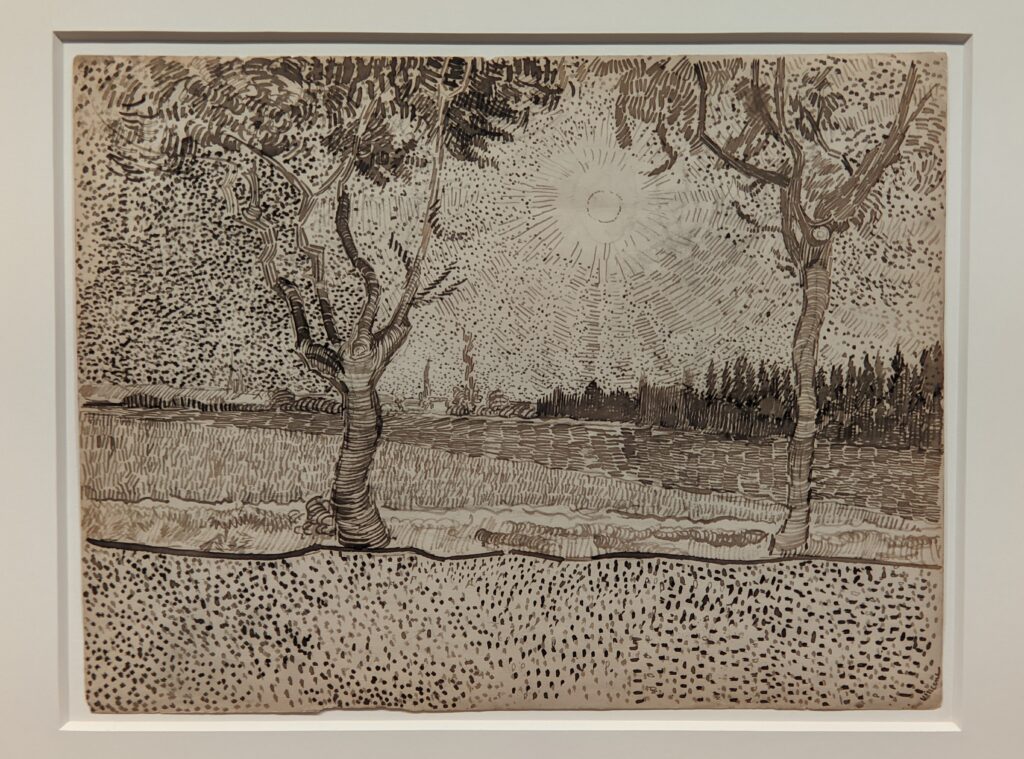

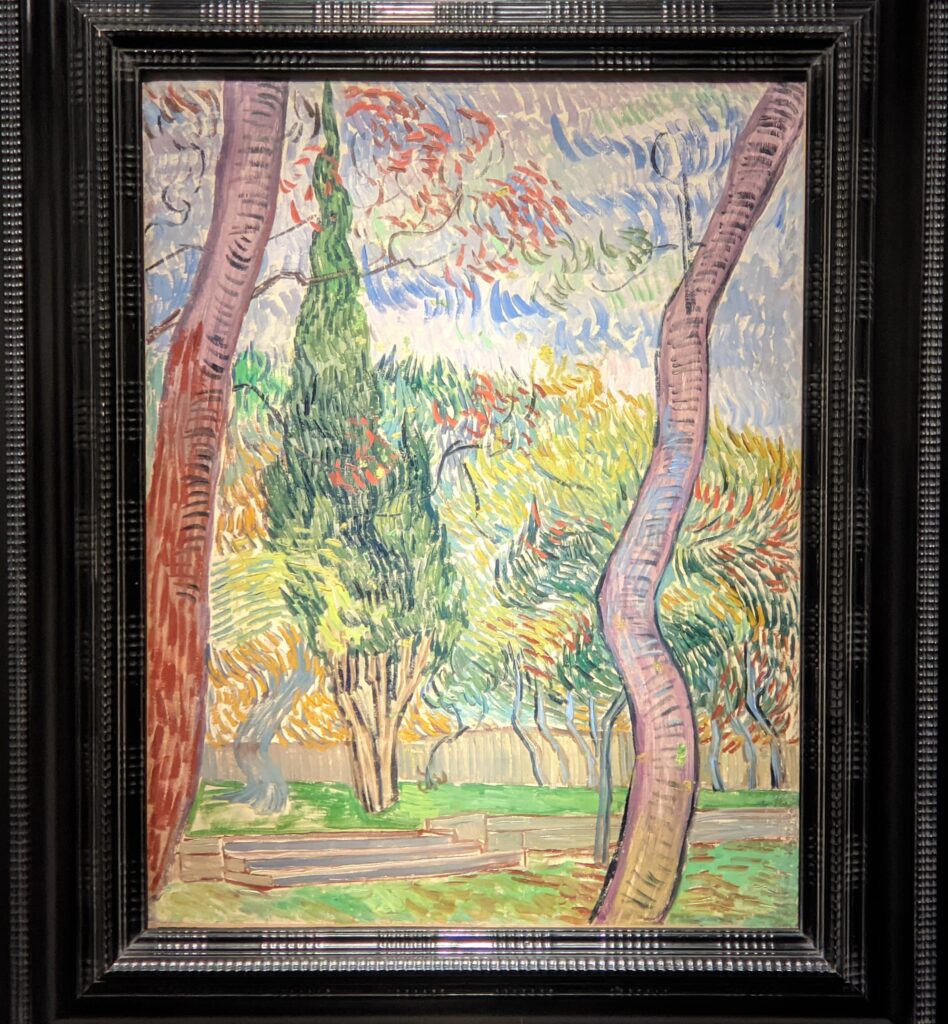

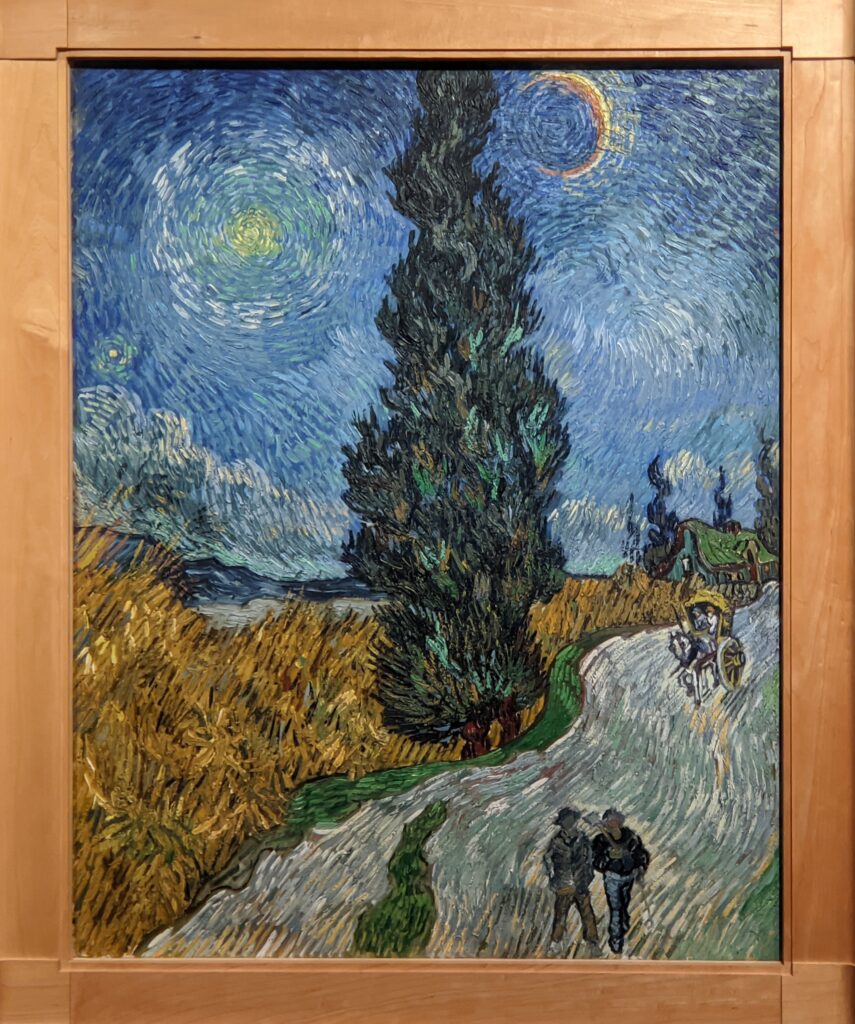

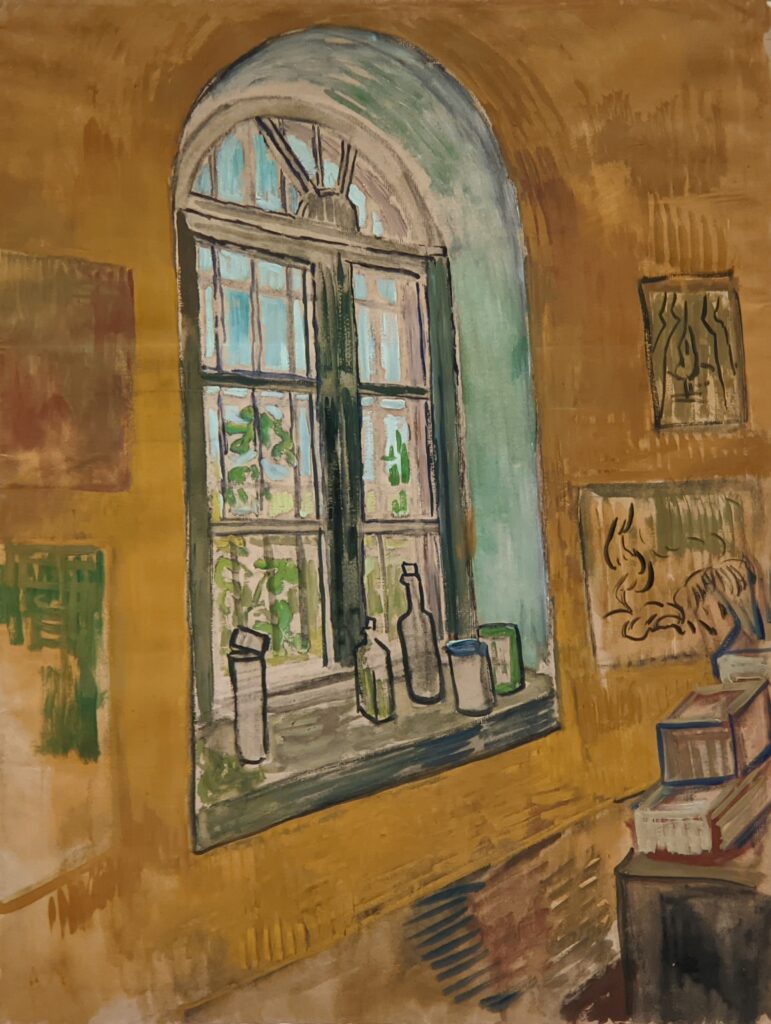

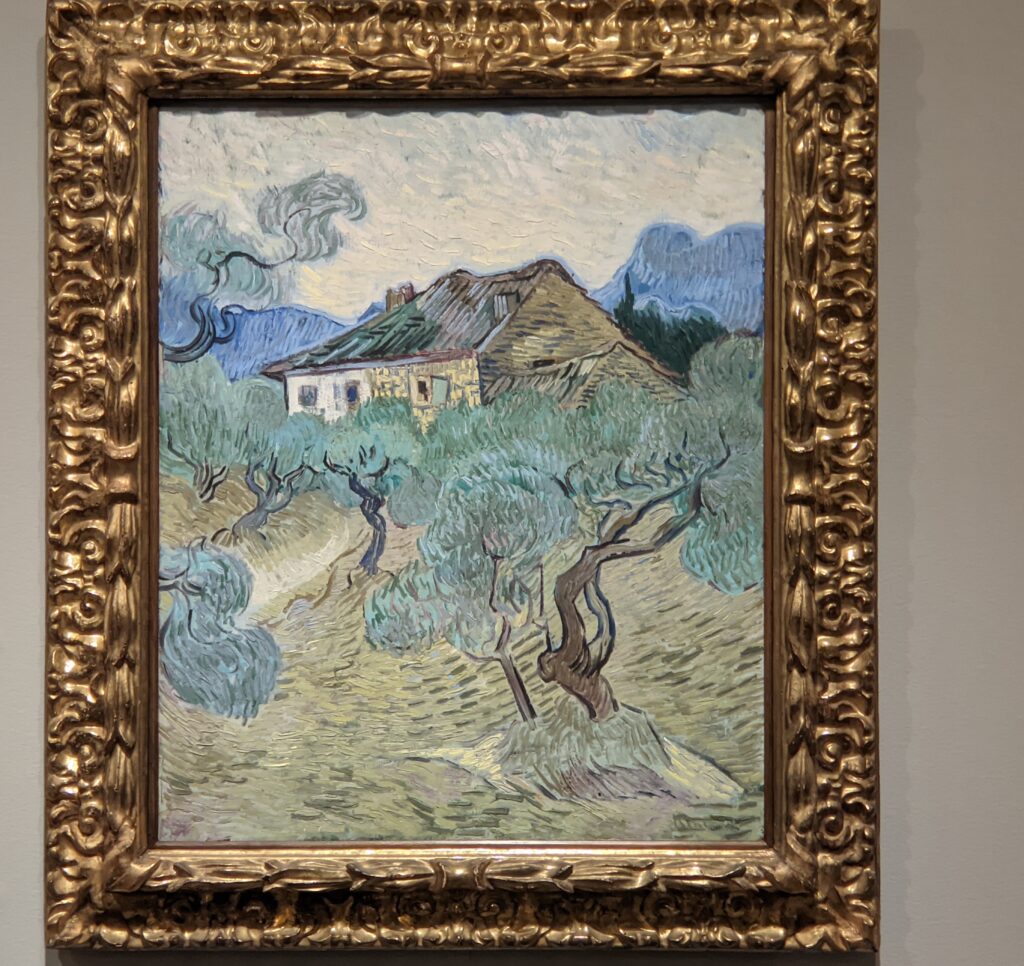

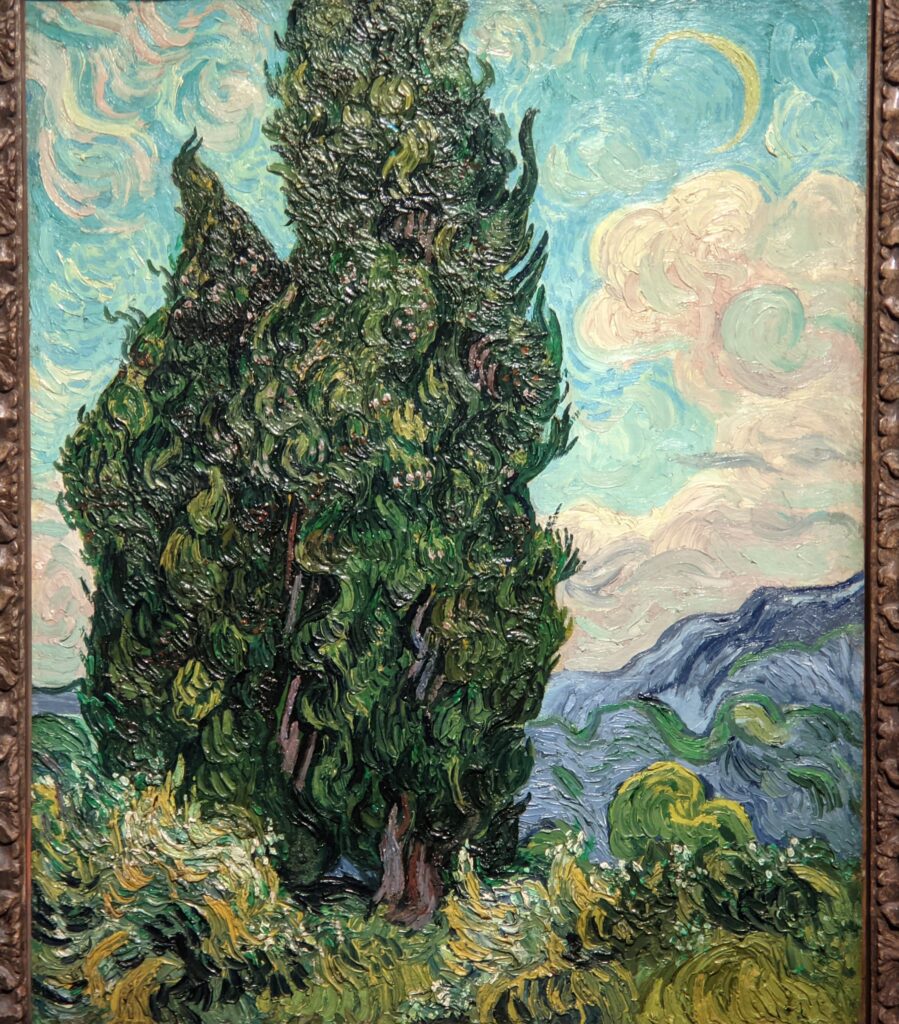

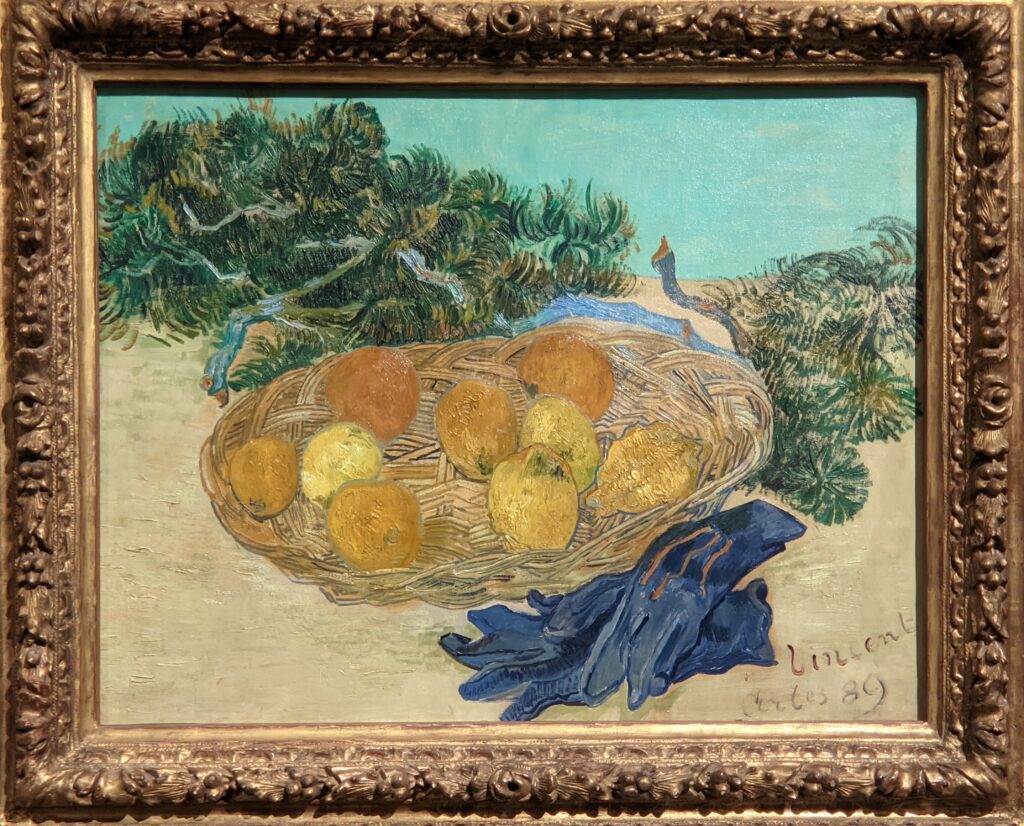

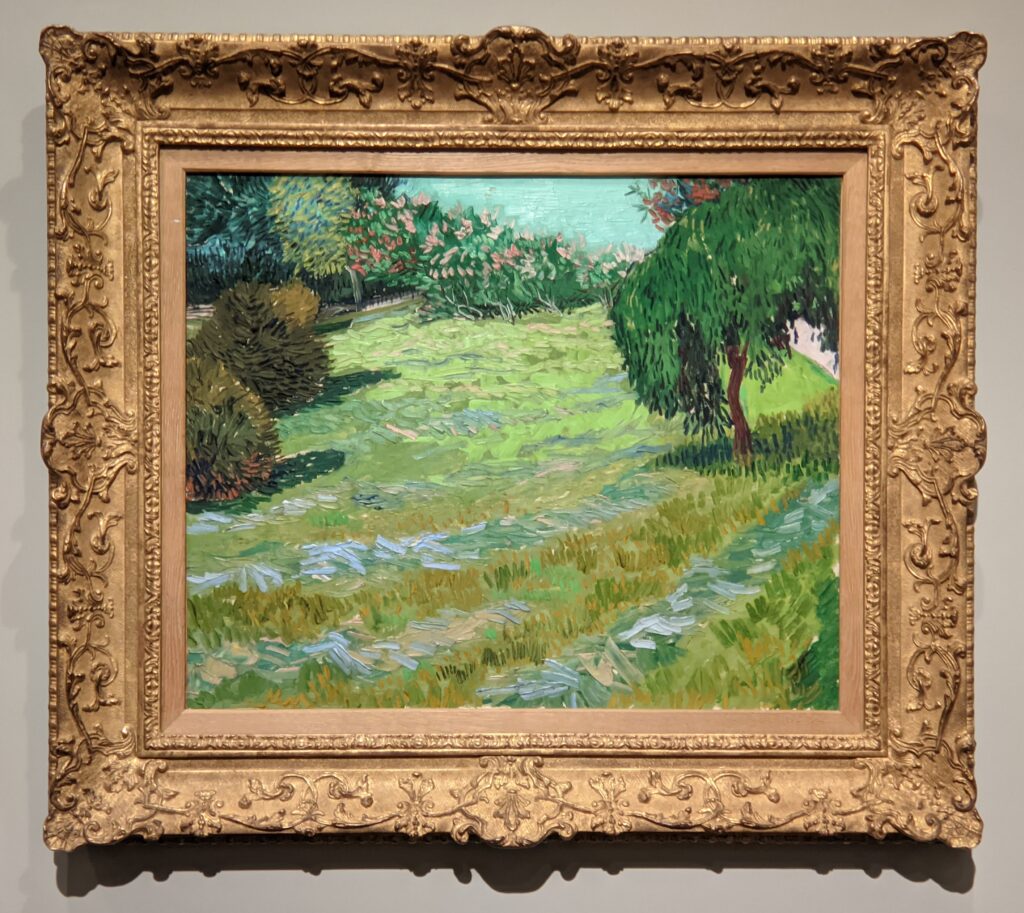

Highlights from a 2023 exhibit dedicated to Vincent van Gogh’s paintings created in the South of France appear below.

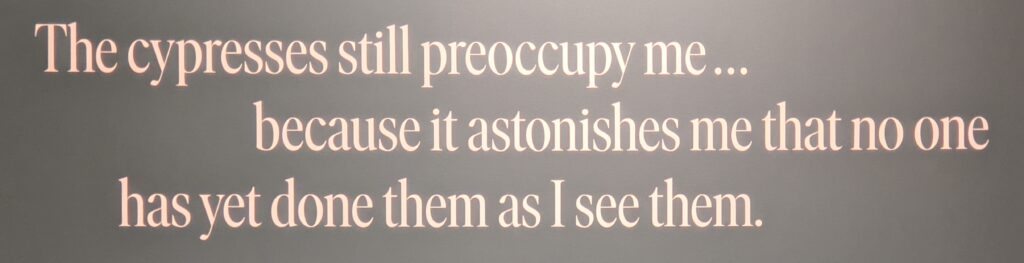

VAN GOGH’s CYPRESSES

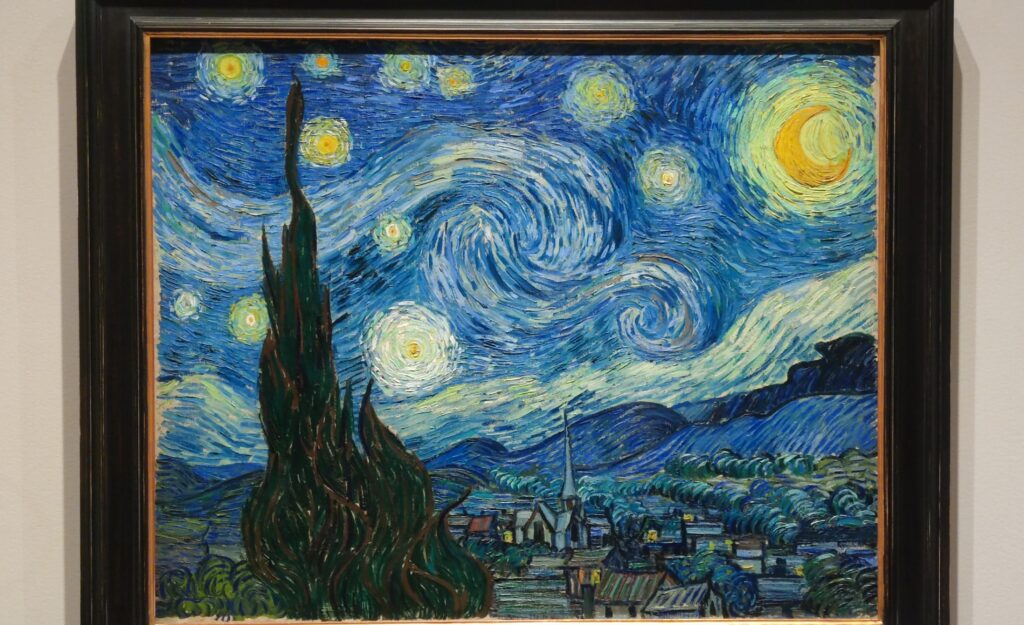

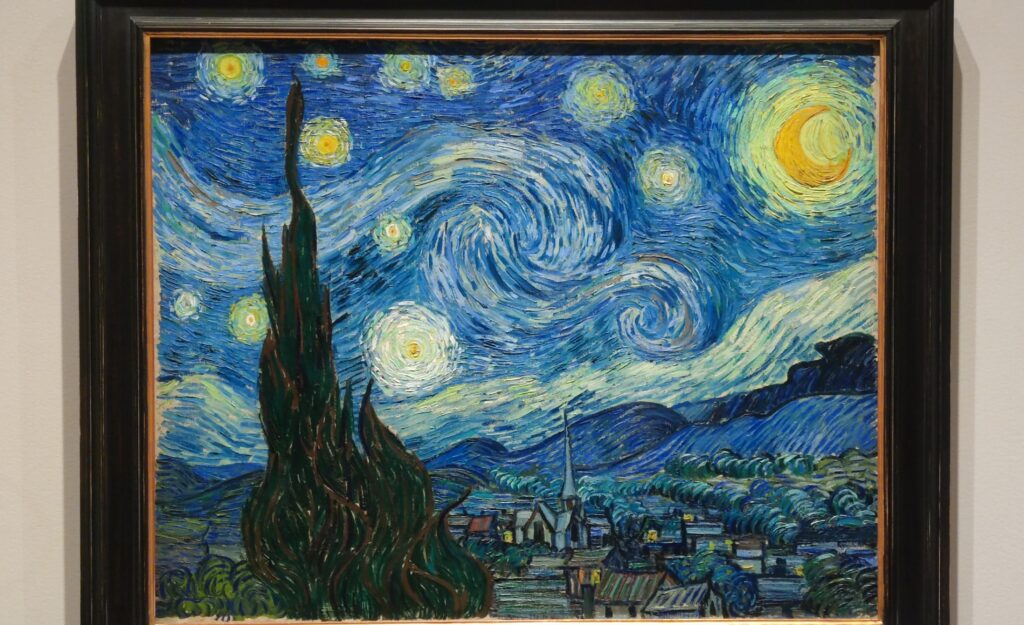

Through August 27, 2023, the Met showed a tightly-conceived thematic exhibit of “Van Gogh’s Cypresses.” Some 40 works of art, including “The Starry Night” (above) from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, illuminated Vincent van Gogh’s fascination with the distinctive evergreen trees that sparked his creativity during his two years in the South of France.

ART LOVERS TIP: Admission to the Met is currently $30 for adults, $22 for seniors 65 years of age and older, and $17 for students. However, New York State residents with valid identification can bring in guests without reservations on a “pay what you wish” basis, meaning the amount you pay for admission is up to you if you enter with someone who lives in New York State! Students from Connecticut, New Jersey and New York also pay what they wish. Children under 12 enter for free.

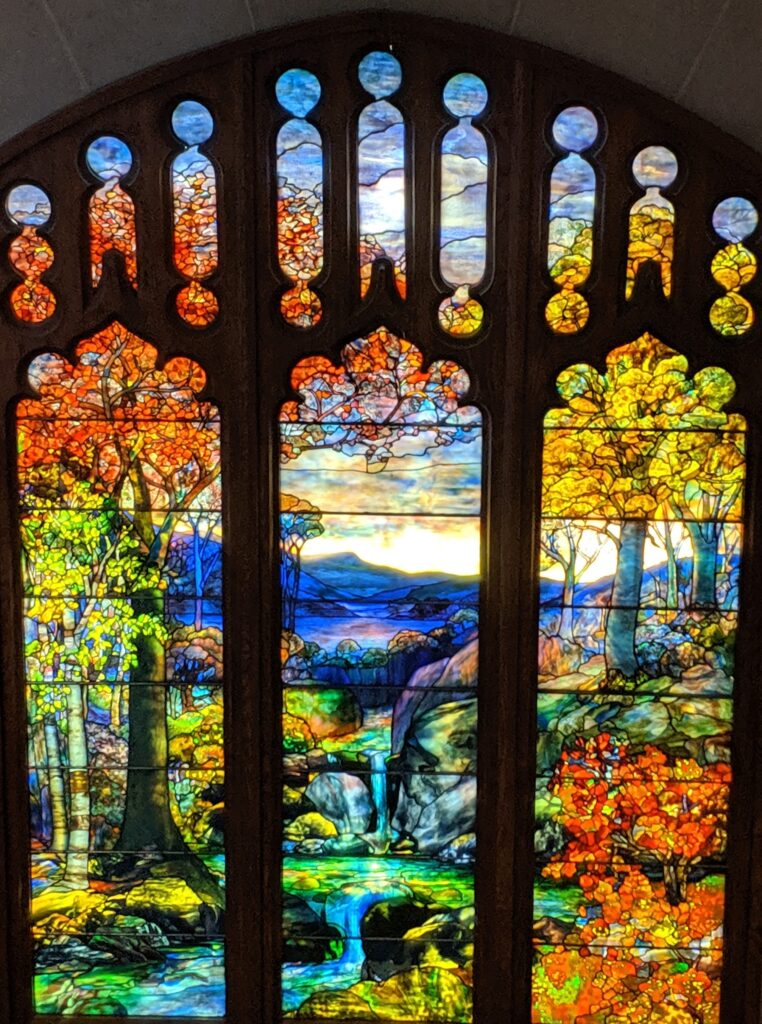

The FRICK COLLECTION in NEW YORK

New York offers something special for each visitor. If the first-class presentation of art on a large scale at the Met is not your cup of tea, then consider the Frick Collection. The first-rate collection of old master paintings at the Frick is without equal in the United States. Henry Clay Frick’s residence at 1 East 70th Street opened to the public as a small museum in 1935. Although this historic home is temporarily closed due to renovation and expansion, Frick’s collection of paintings from the Renaissance to the early 20th century is currently on display at 945 Madison Avenue at East 75th Street, Thursday through Sunday from 10:00 until 5:45 in the afternoon.

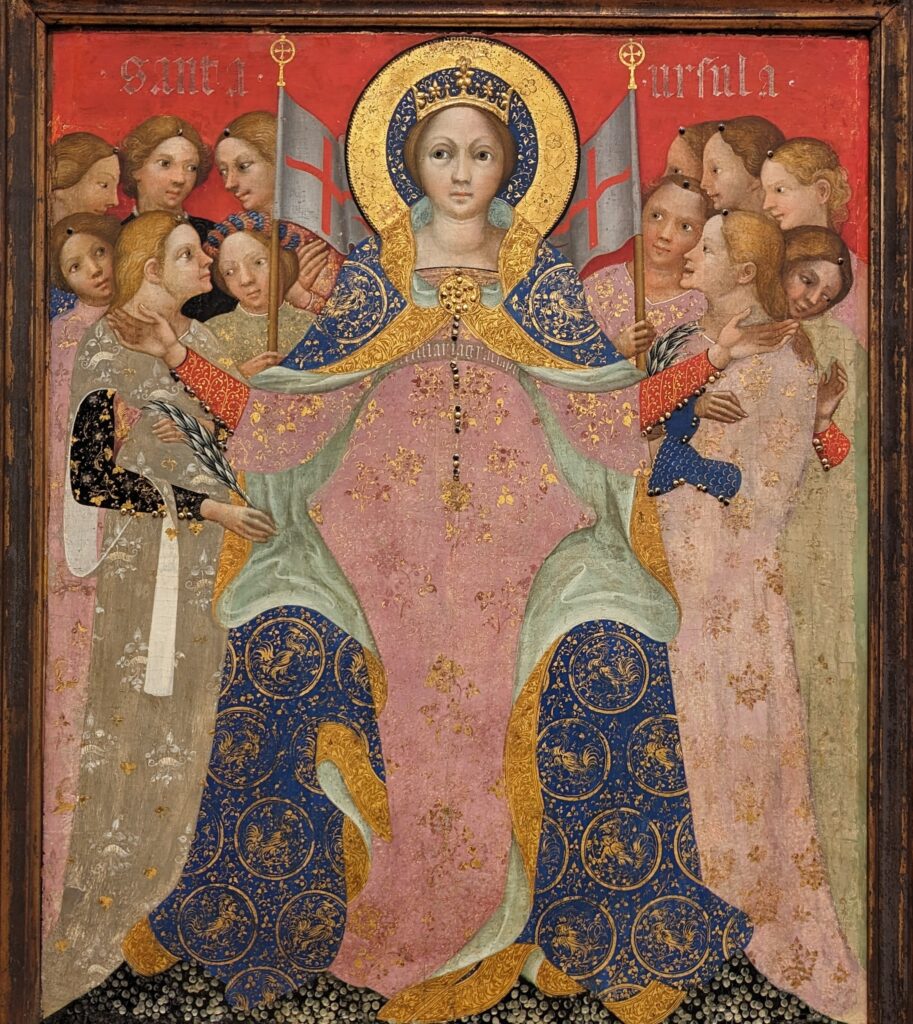

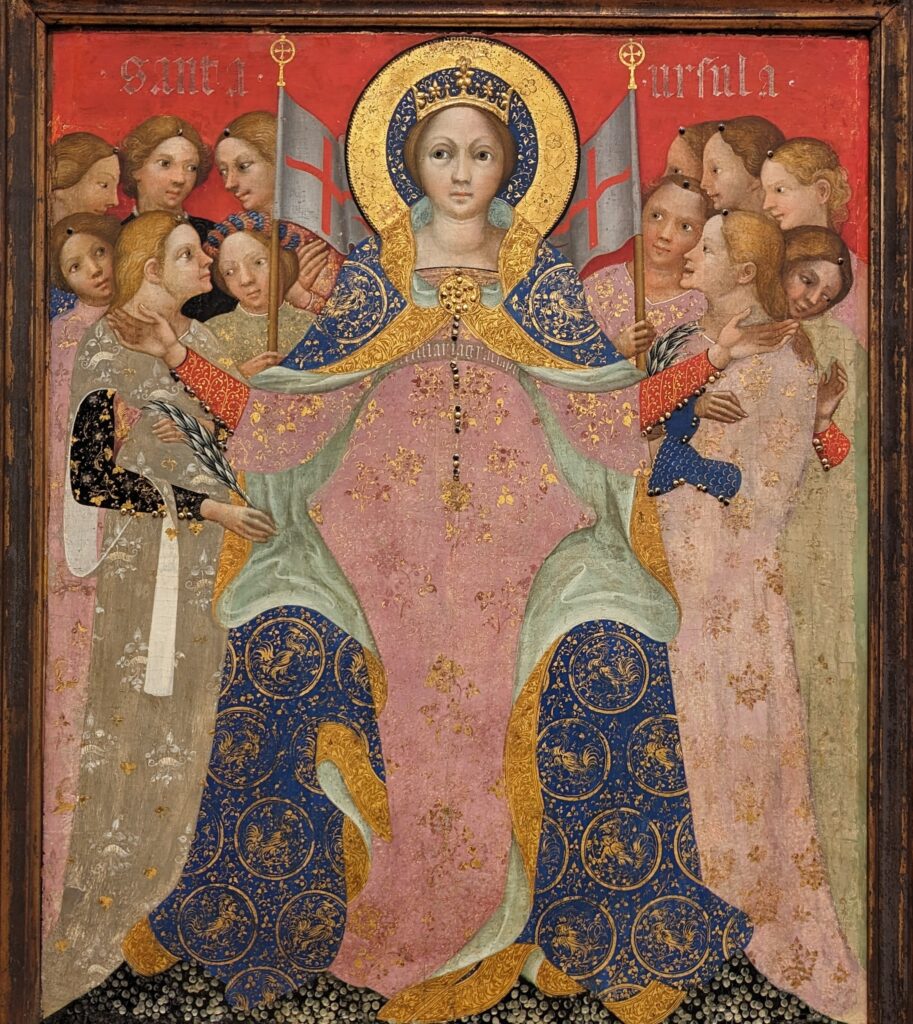

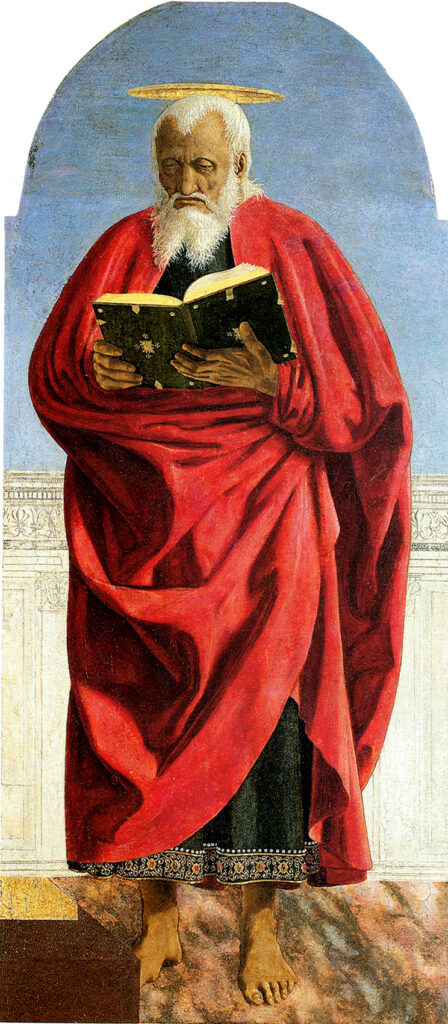

Italian Masters

The Finest Netherlandish Paintings in New York

British Art

Painters in Spain & France

All of the decorative objects, furniture and canvases at the Frick Collection are of the highest quality, and slightly more than half of the paintings were chosen by Henry Frick himself before his death in 1919. It would be impossible for us to focus our attention on one work of art from this preeminent small museum; however, we do have two favorites: Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert and Johannes Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid.

With five Vermeers in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and three more at The Frick, you have the opportunity to appreciate so many of these rare paintings within a 10-block radius. Moreover, Mistress and Maid is one of the most interesting Vermeers, and the fact that it was the last painting that Henry Frick added to his collection demonstrates his growth and sophistication as a collector. You should also seek out the art of Piero della Francesca — of the seven paintings by this artist in the United States, you will find four at The Frick — as well as Fragonard’s series entitled The Progress of Love. While these Fragonards are usually installed in a Rococo drawing room inside the Frick mansion (with the attendant panels hanging over doors and next to windows), you now have the exceptional opportunity to view the 14 paintings that comprise The Progress of Love individually and up-close at the Frick Madison.

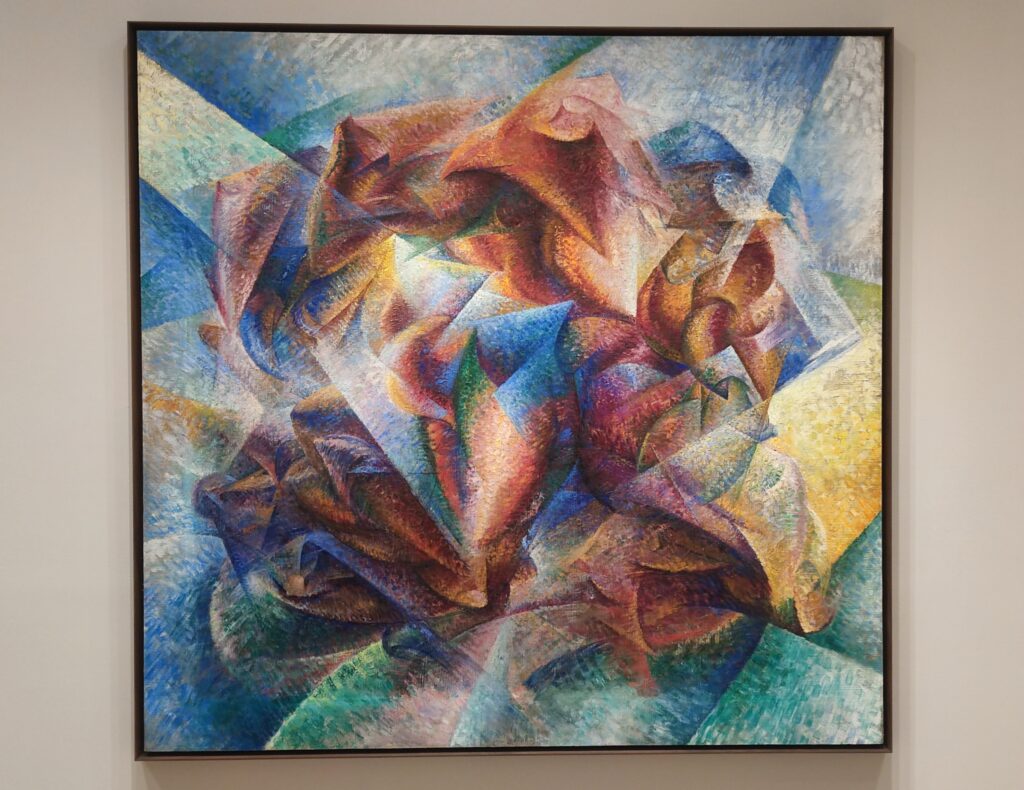

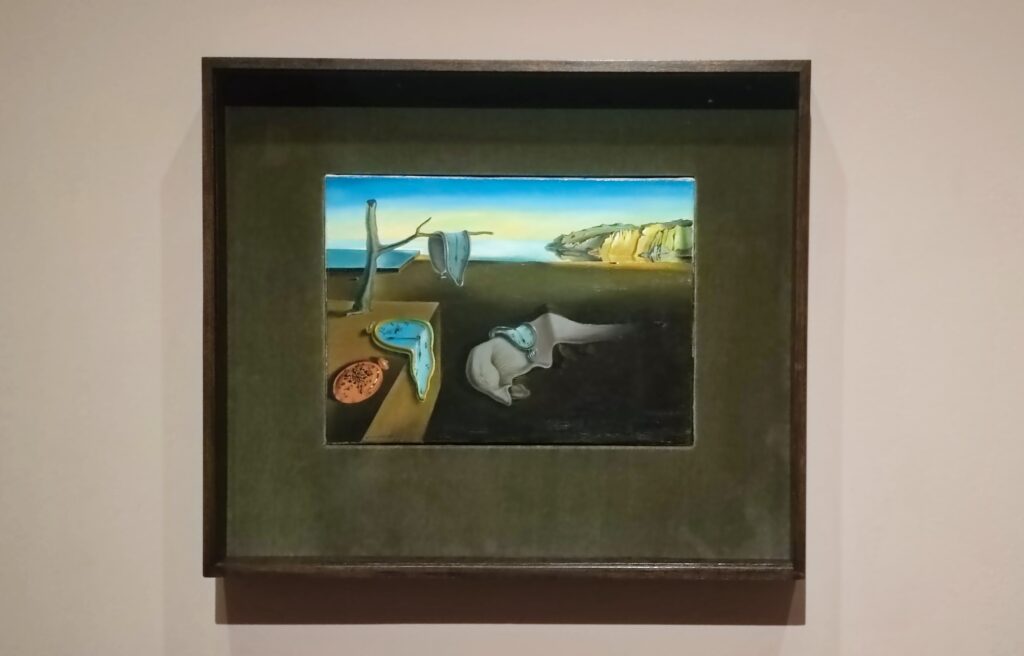

The MUSEUM OF MODERN ART in NEW YORK

We at ArtLoversTravel have a love/hate relationship with New York’s Museum of Modern Art (colloquially, “MoMA”). We have included MoMA among the top three museums to visit in NYC because it is the world’s most influential institution devoted to modern art, and comparable museums envy the breadth of MoMA’s collection. In addition, the Museum of Modern Art is extremely popular, consistently ranking among the 15 most visited art museums in the world (with over 1,150,000 visitors in 2021, despite the pandemic). To draw a comparison, the Met received nearly 2,000,000 patrons during the same year, and the third most popular venue for art in New York was the Whitney Museum of American Art with about 500,000 visitors annually.

The Cons & the Pros

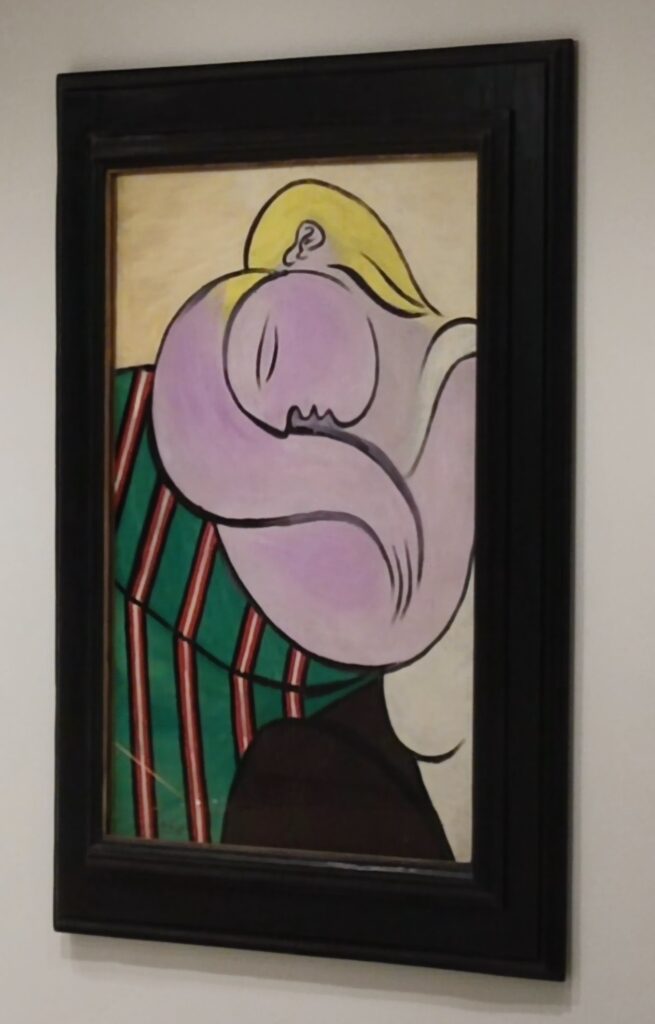

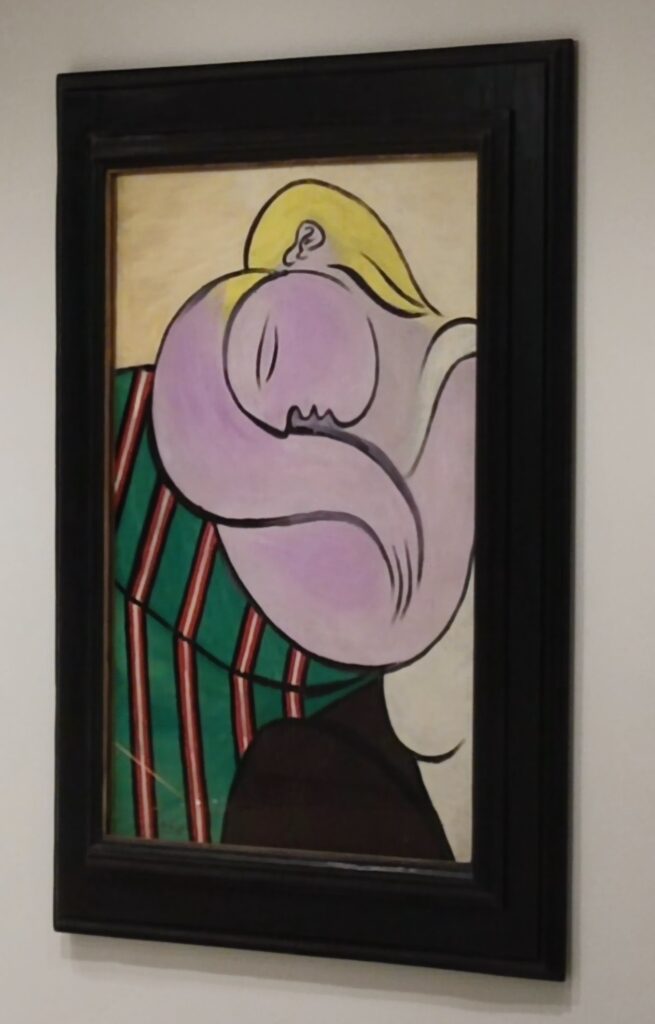

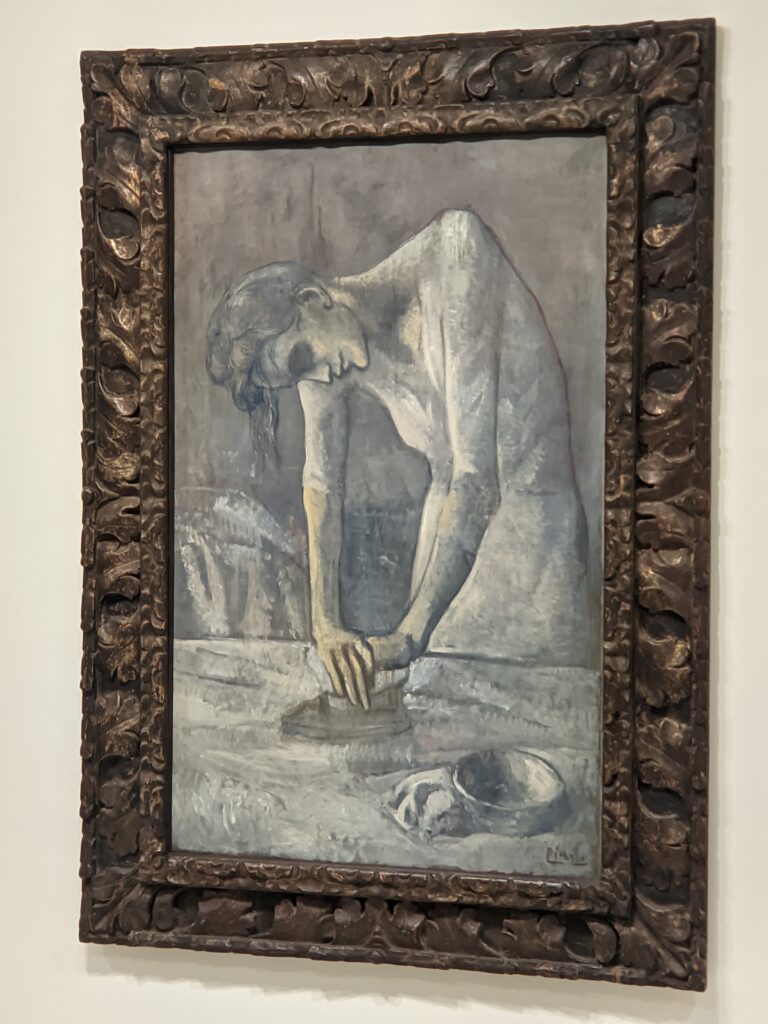

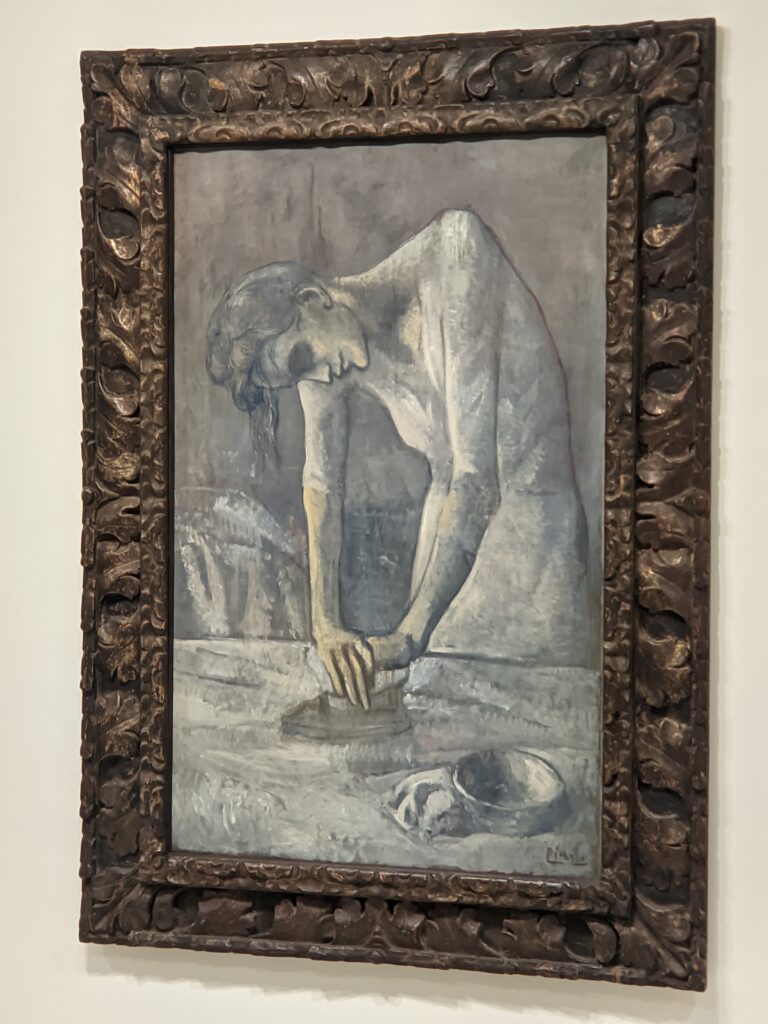

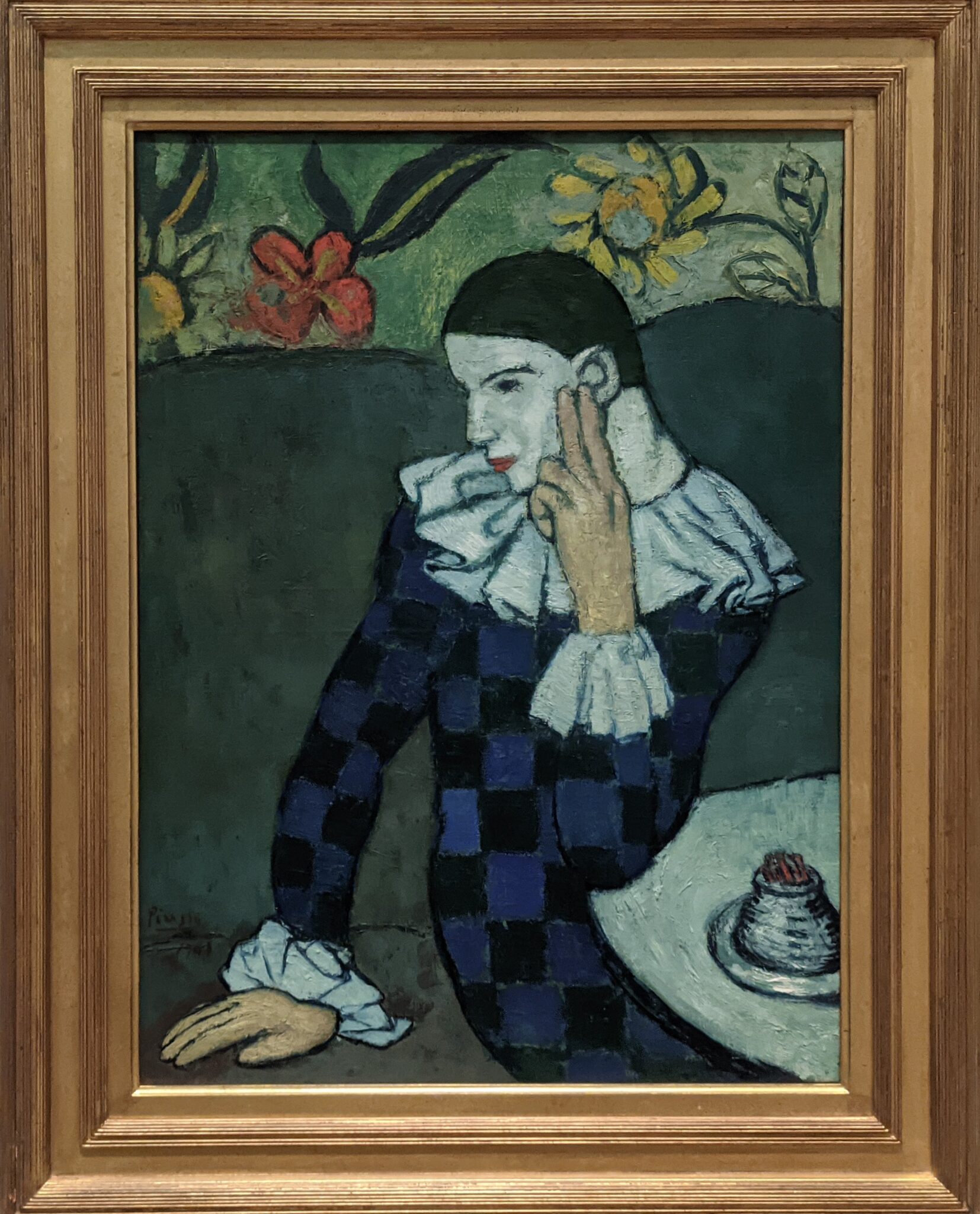

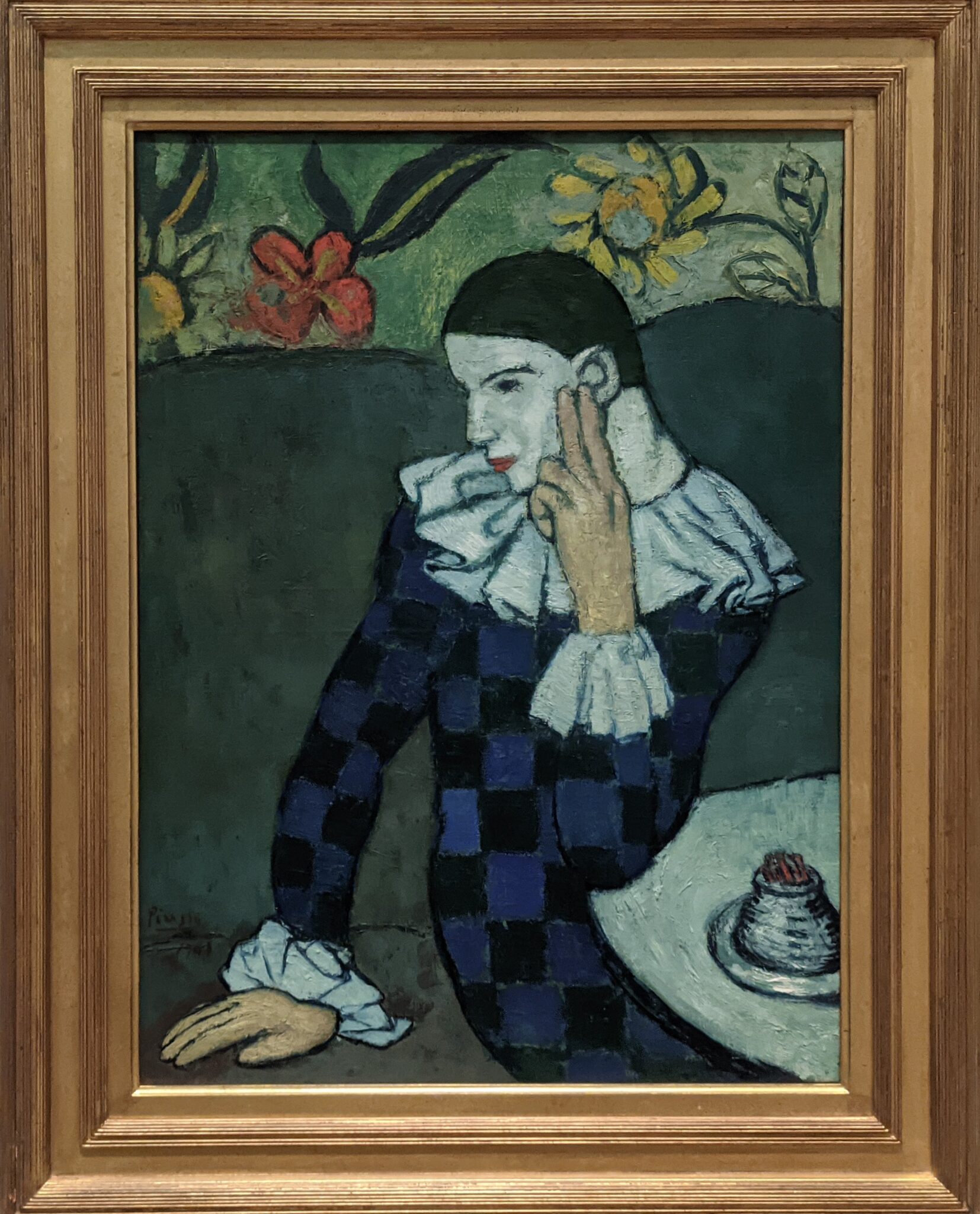

One disadvantage of owning the most impressive collection of modern and contemporary art is the fact that only about 10% of the Museum of Modern Art’s collection is on display at any one time. We have ambivalent feelings about MoMA’s constant acquisition of so many masterpieces when 90% of that art will end up housed in temperature-controlled storage for a seemingly endless number of years. MoMA normally shows about 24 Picassos, for example, even though MoMA owns 1,221 works of art by Pablo Picasso.

We also have mixed feelings about how this museum curates its holdings and, in general, the gallery space at MoMA, which at times has the ambiance of a crowded mall. Of the six departments at this museum, we find that the two departments with the best curators — “Architecture and Design” and “Drawings and Prints” — are given the least amount of space. The other four departments are Film, Photography, Painting & Sculpture, and Media & Performance. In fairness, many museums confront similar problems. The Louvre shows 8% of its collection, the Guggenheim 3%. Of course, there are success stories, which MoMA would be wise to contemplate. Vienna’s Albertina Museum (one of our favorites) possesses millions of works on paper with the space to show “less than 1% — maybe even 0.1% — of our collection” of drawings, according to Christian Benedik. The Albertina’s original owners, however, mandated that a facsimile of every graphic work of art be readily available for viewing by the public. Historically, MoMA’s solution has been to expand its space at 11 West 53rd Street for the presentation of modern art, while reserving its location in Queens (MoMA PS1) for the sole purpose of exhibiting contemporary art. In order to show more of its art, perhaps it is time for MoMA to open satellite galleries in the USA, especially in culturally underserved communities, and abroad.

MoMA at Its Best

Whether you are a novice or an art aficionado, the Museum of Modern Art in New York is the perfect place to appreciate the development of modern Western art by admiring one masterpiece after another — and we do mean “one.” If you want to see the art of Edgar Degas “in depth,” go first to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

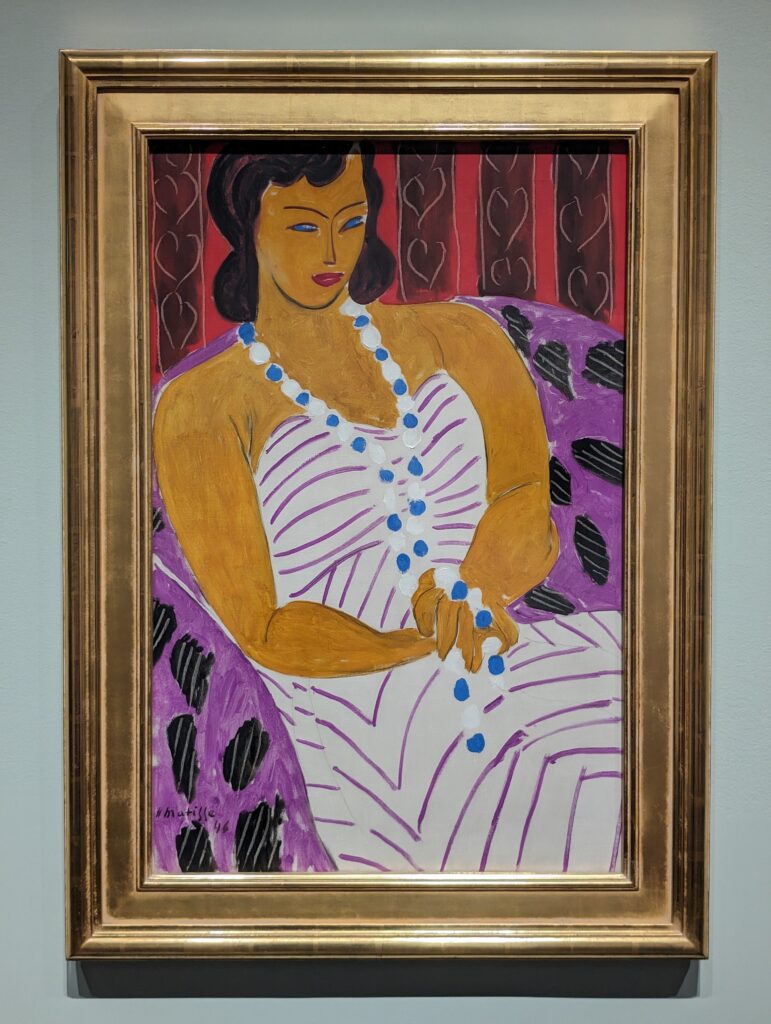

At MoMA we saw only one painting by Degas on public display and yet, through MoMA’s seamless chronological presentation, it was visually quite easy to see how Degas’ experimentation with color intensely influenced the palette of Paul Gauguin, and then how Derain, Matisse, Bonnard and Picasso used Gauguin’s paintings as a touchstone to judge their own successes or shortcomings with color.

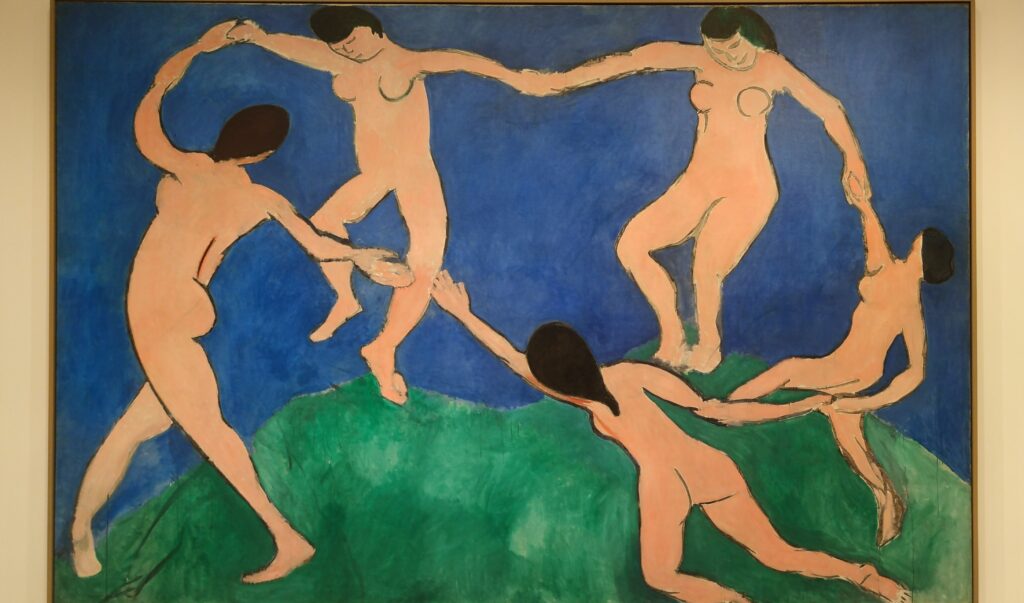

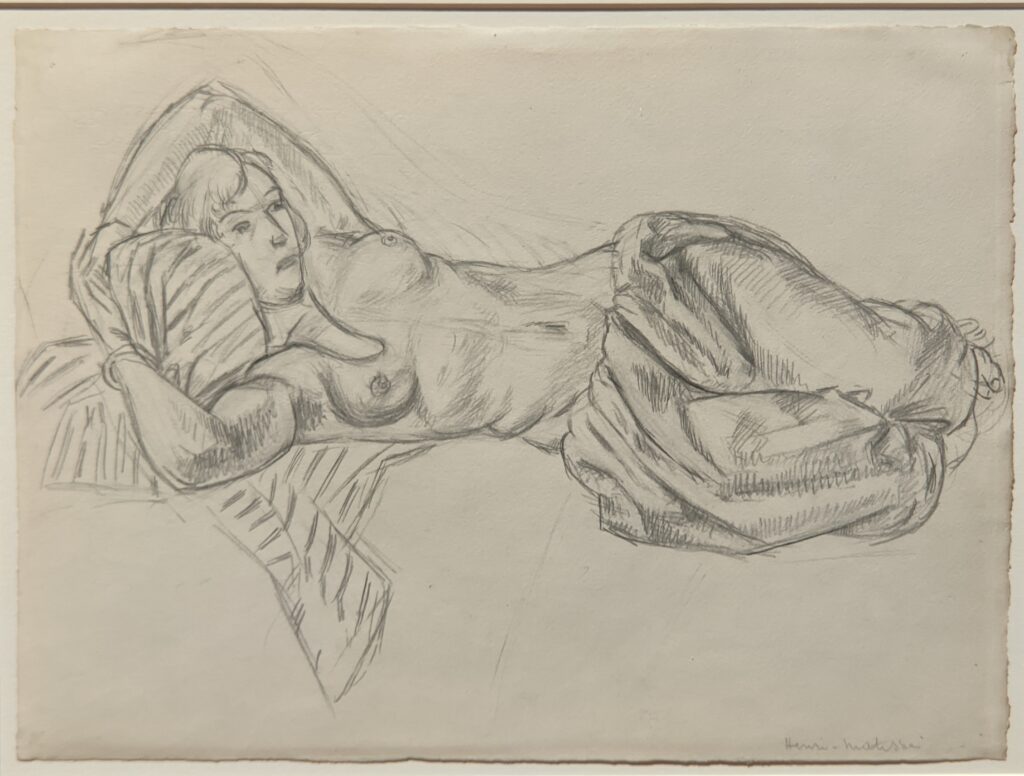

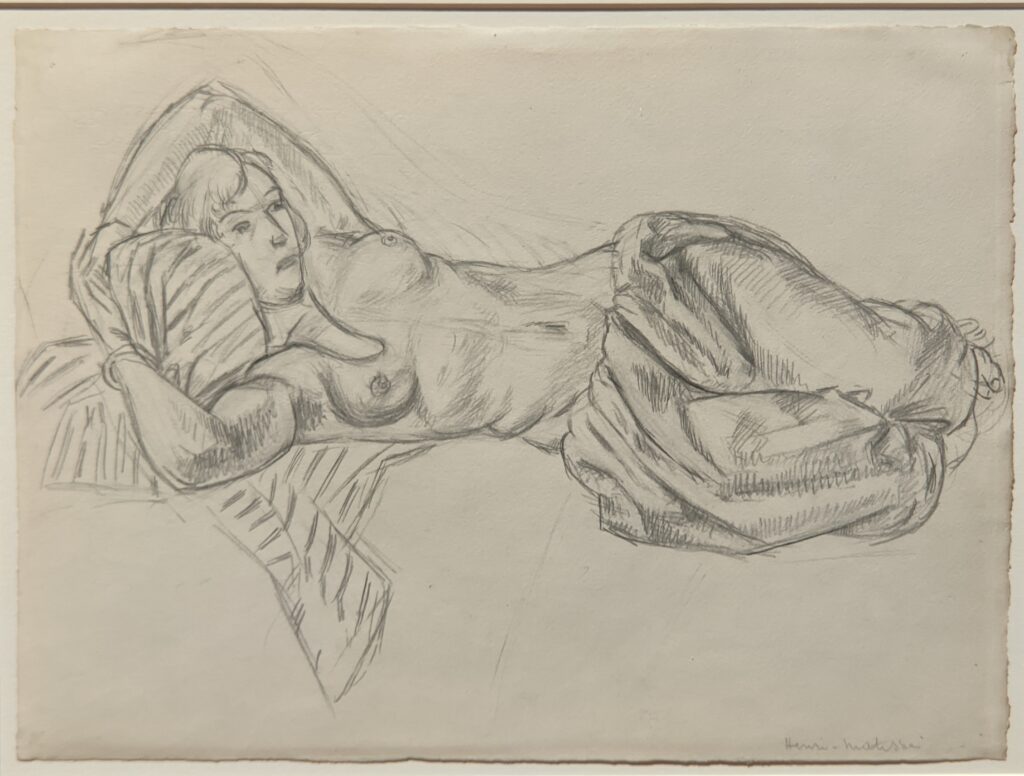

Come to New York If You Wish to Gain a Better Understanding of Matisse & Picasso

Henri Matisse is known for his mastery of the expressive language of color, and Pablo Picasso is credited as the first to deconstruct form and perspective (through the Cubist movement, collage, and constructed sculpture). Yes, these two greats were in opposing camps, but not enough scholarly attention has been devoted to how they learned from and spurred on each other. After his Blue Period (1901 — 1904) and Rose Period (1904 — 1906), Picasso found inspiration in Matisse’s Fauvist experimentation, the hostility Matisse’s paintings received at the Salon d’Automne (1905) and the fiasco that resulted when “The Joy of Life” (“Le bonheur de vivre,” now in the Barnes Foundation) by Matisse was exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants (1906). Critics of Matisse were concerned about the end of French painting. Paul Signac (who had purchased early works by Matisse) wrote, “Matisse, whose attempts I have liked until now, seems to me to have gone to the dogs. Upon a canvas of two-and-a-half meters, he has surrounded some strange characters with a line as thick as your thumb. Then he has covered the whole thing with flat, well-defined tints, which — however pure — seem disgusting.”

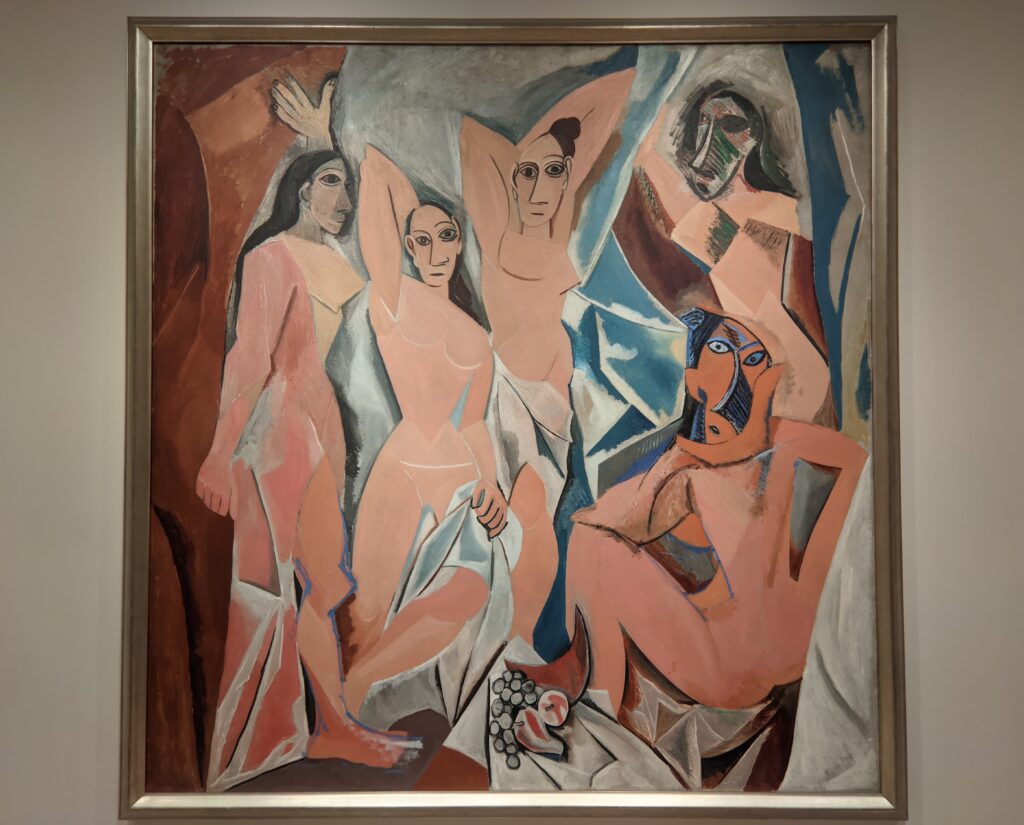

Truth be told, the non-realistic figures, complex spontaneous brushstrokes and bold colors of Fauvism were inspired by African art, and it was Matisse who showed Picasso a wooden Kongo-Vili figurine around 1906-07 which led Picasso to experience a “revelation” while viewing African art inside the ethnographic museum at the Palais du Trocadéro.

Having seen Le bonheur de vivre “Pablo Picasso, who, in an effort to outdo Matisse in shock value, immediately began work on his watershed Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (above), according to a curator at the Barnes Foundation. Be that as it may, thanks to Matisse’s inspiration it was at this time that Picasso began his African Period (1907 — 1909). Finally, from 1909 to 1912 both men realized their most radical contributions to modern art: Picasso invented Analytic Cubism, while Matisse was creating his Color-Field Revolution.

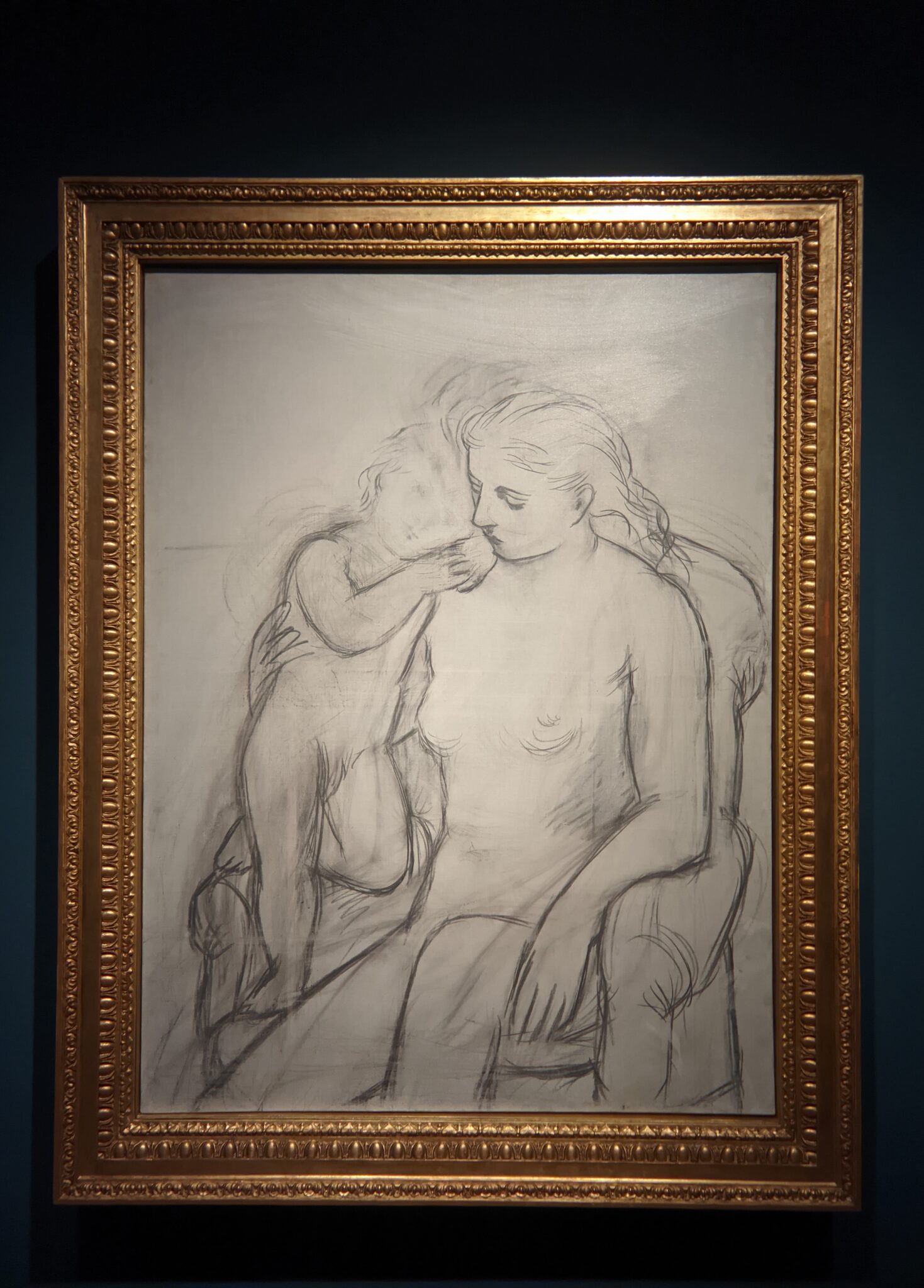

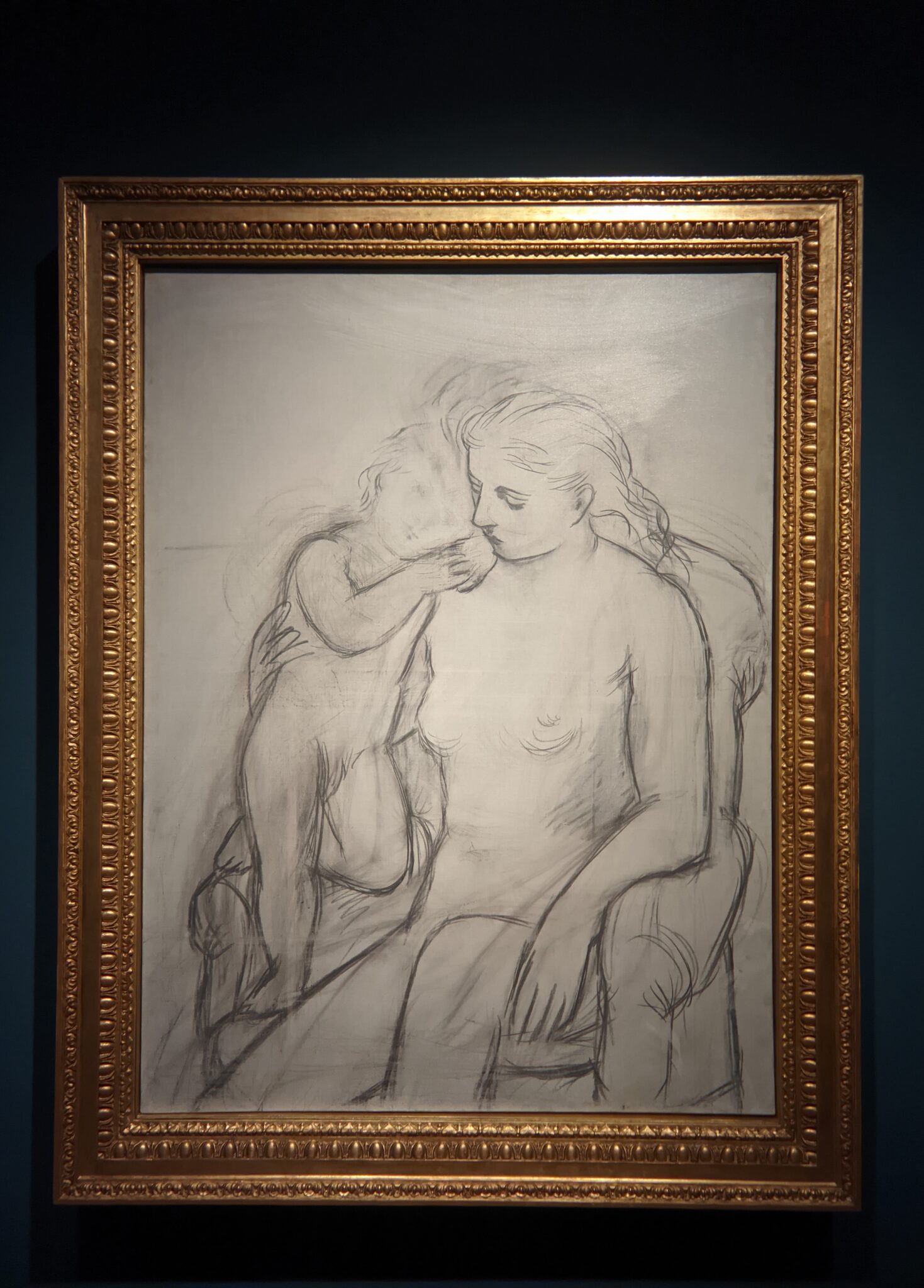

It is noteworthy that in the 1920s both Matisse and Picasso softened their most extreme approaches to art (portraiture, in particular) — a time when Matisse’s orientalist odalisques can be compared to Picasso’s neoclassicism, as well as Derain’s return to traditionalism during the so-called “return to order” in the art world following World War I.

In retrospect, theirs was a fruitful rivalry. The older Matisse had motivated Picasso in 1906 to explore non-Western art and advance more radical approaches. In turn, a few years later Cubism, the first abstract movement in art, proved to be something that interested Matisse, though ultimately he rejected it. As you proceed through the Museum of Modern Art, you may fairly conclude that Matisse was inspired by Picasso to incorporate certain aspects of the deconstruction of form into his expressive style of painting that emphasized flattened forms and decorative patterns, as one can immediately recognize in “Still Life after Jan Davidsz. de Heem’s ‘La Desserte'” (above) and “The Moroccans” (below).

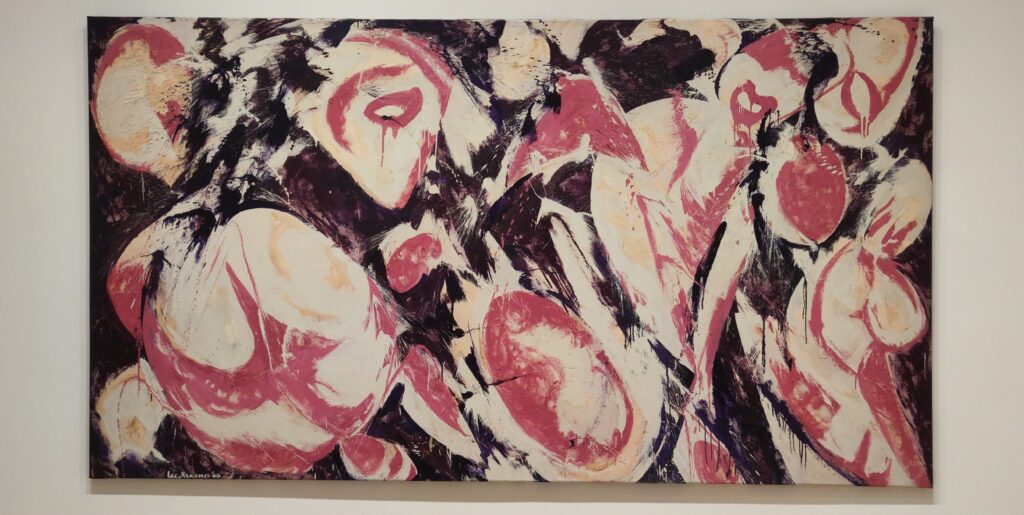

A Protest by Women in New York

In 1983, an expansion project at MoMA more than doubled its gallery space. In June 1984, there was a protest in front of the museum by 400 women artists to bring attention to the lack of female representation in “An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture,” its opening exhibition following the museum’s expansion which featured only 14 women among the 165 contributing artists. Today, the holdings at MoMA represent more than 13,000 artists — 20% female, 80% male and 3 non-binary.

Here, we have presented some of our impressions of the Museum of Modern Art in New York — its strengths and failings. We urge you to visit MoMA, and we hope you will share your experience with us and our readers.

If you are interested in learning more about the “KARL LAGERFELD: A Line of Beauty” exhibit previously held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and additional paintings by the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists (including Vincent van Gogh) on view at the Met, please pay a visit to our article entitled “New York City — Fashionable Exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum.”