Sargent and Paris – Triumph: an Epic Decade of Genius to See in New York

John Singer Sargent, an American painter renowned for his portraits and mastery of light, became a pivotal figure whose experiences illuminate the connection between Sargent and Paris during the vibrant art scene of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in 1856 to American parents in Florence, Italy, Sargent spent his childhood in Europe. His family moved seasonally, seeking affordable lodging and temperate climates, which allowed him to immerse himself in diverse cultures from a young age. Before he turned eighteen, he had lived in Italy and France, traveled extensively across the European continent, and become fluent in multiple languages. Sargent’s mother, an amateur watercolorist and inveterate sightseer, played a crucial role in cultivating his artistic inclinations by encouraging him to sketch daily. These formative experiences, coupled with years of serious practice and lessons, ensured Sargent was well prepared when he enrolled at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence in 1873.

The allure and artistic gravity of Paris soon called. He and his parents determined that the French capital would be “the best place” to truly nurture his burgeoning talent. Arriving in Paris in May 1874, the precocious eighteen-year-old American art student found a city in rapid transformation. It was becoming the undisputed center of the European art world, energized by the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) and the foundation of a new government. Determined to make his mark as a painter, Sargent plunged into the city’s vibrant cultural life.

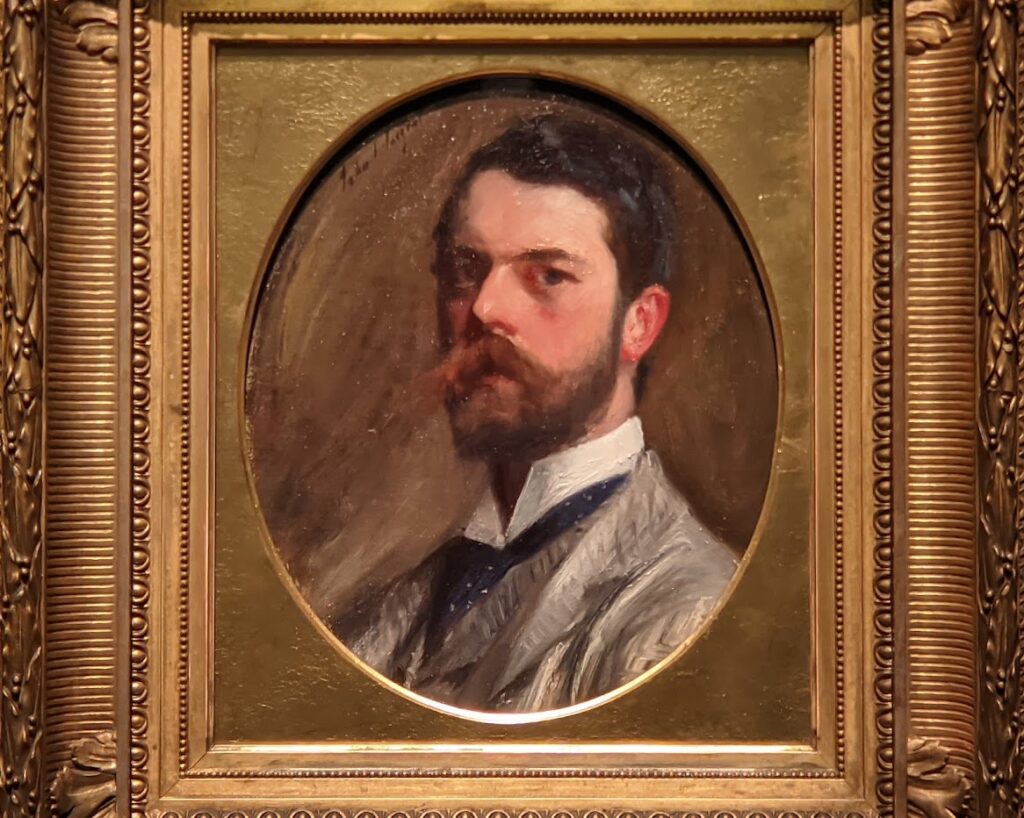

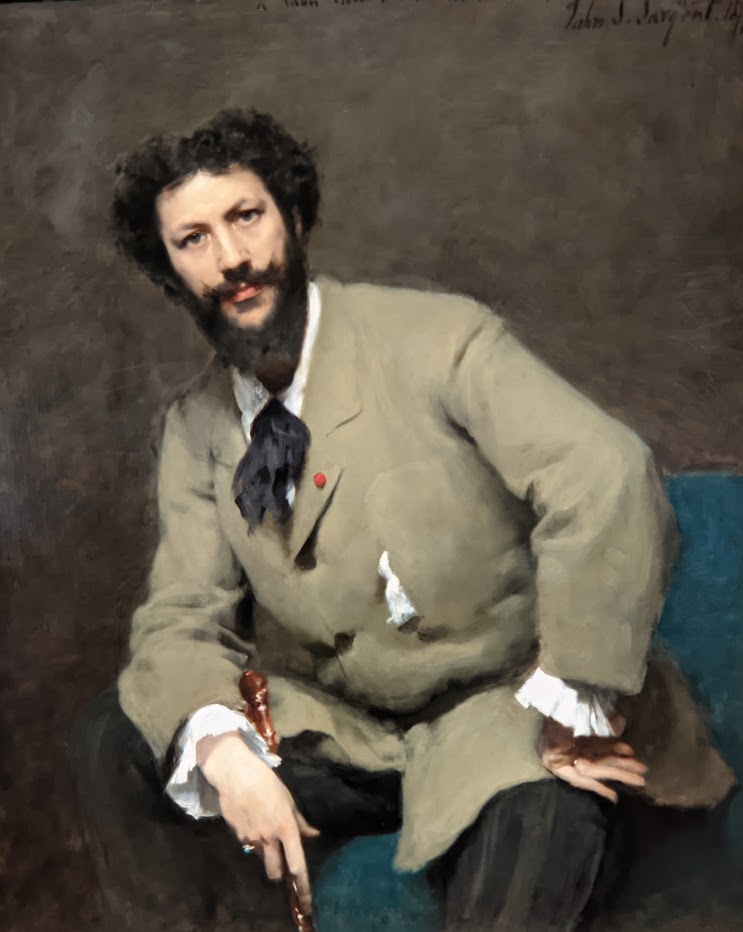

His formal art education commenced under the guidance of the leading French portraitist Carolus-Duran (1837–1917), and he also enrolled at the prestigious state-sponsored school, the École des Beaux-Arts, attending intermittently through 1877.

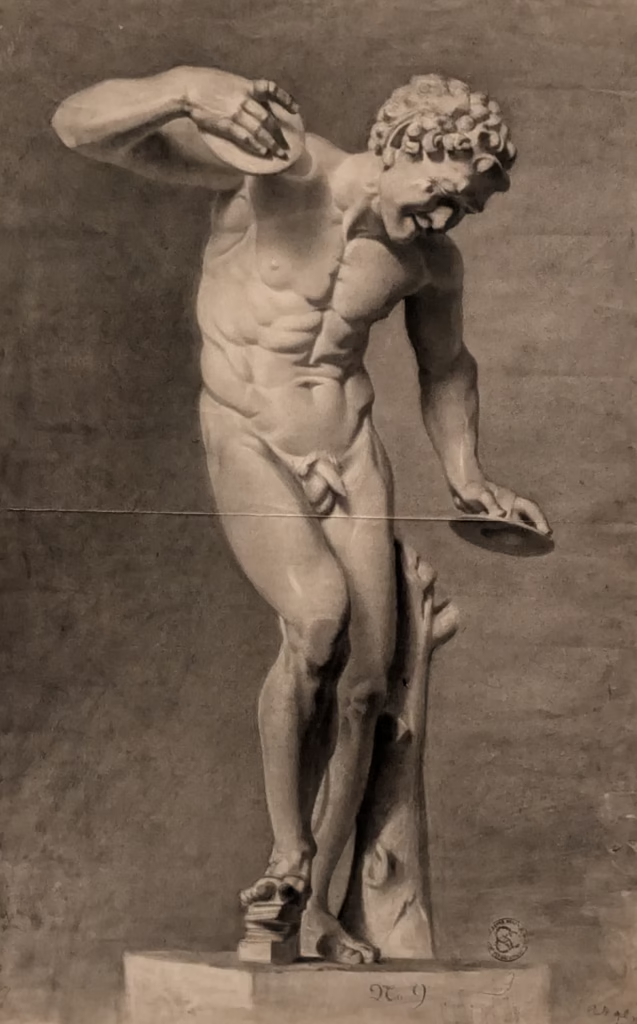

Sargent eagerly absorbed all that Paris offered, from studying the magnificent antiquities at the Louvre Museum to engaging with the avant-garde paintings of the Impressionists. This period was instrumental in honing Sargent’s skills, and his knowledge of art history was significantly enriched by the vast array of historical and contemporary art on display throughout Paris. The unique Parisian environment, where traditional art forms thrived alongside groundbreaking avant-garde practices, fostered a culture of innovation that profoundly influenced Sargent’s artistic evolution and the distinctive style of Sargent’s portraits that would soon captivate the 19th-century art world.

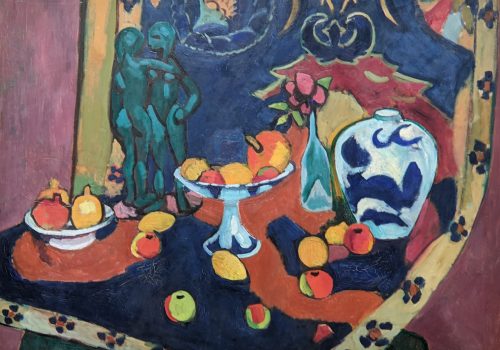

The late 19th century in Paris was a crucible of artistic development, witnessing the rise of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Sargent’s own interest in painting outdoors was significantly stimulated by his contemporaries, particularly the Impressionists. A pivotal moment was his attendance at the independent group’s 1876 exhibition in Paris, which led to a lifelong friendship with one of its founding members, Claude Monet (1840–1926). Monet’s explorations of color and light deeply resonated with Sargent.

As a multilingual and cosmopolitan figure, Sargent moved with ease among diverse circles of artists, writers, and patrons, many of whom became subjects for his daring portraits. These relationships within the international community — comprising fellow students, established artists, and influential patrons — were critical to his development and success. Constantly traveling in search of inspiration, he created picturesque compositions not only in Paris but across Europe and North Africa. His innate ability to blend traditional techniques with modern sensibilities (combined with an expressive technique), perfectly suited to experimentation and the immediacy of plein-air painting, quickly set him apart. Both in Paris and further afield, his work rapidly earned him a reputation as a progressive, modern painter. Indeed, just three years after his arrival in the city, he launched his public career at the prestigious Paris Salon, the celebrated annual art exhibition, where he showed a portrait of his friend Fanny Watts.

The rich cultural tapestry of Paris, woven from diverse influences and groundbreaking artistic ideologies, provided the essential backdrop for Sargent’s remarkable journey. This vibrant scene was the catalyst for his distinctive approach to portraiture, forging a path that would ultimately lead him to international acclaim and a lasting impact on the world of art.

“Sargent and Paris” Was on View in New York City at the Met & in Paris at the Musée d’Orsay in 2025

A collaborative exhibition organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Musée d’Orsay, “Sargent and Paris” meticulously followed John Singer Sargent’s meteoric rise in the French capital across one remarkable decade, beginning with his arrival in Paris in 1874 (at age 18) through the mid-1880s. It offered art lovers a unique opportunity to appreciate how Sargent’s experiences in Paris profoundly shaped his artistic legacy, illuminating his artistic beginnings and providing a keenly observed view of Parisian society and its dynamic art world.

Highlights of the Exhibition

The “Sargent & Paris” exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art presented an impressive and thoughtfully curated array of artworks, prominently featuring the masterpieces of John Singer Sargent. Celebrated for his striking portraits and an intuitive, almost unparalleled understanding of light and color, Sargent’s works from this period represent a pinnacle of artistic excellence during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Among the many featured pieces, “Madame X” (Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau) undeniably stood out. Now an icon of the Met’s permanent collection, this painting was one of Sargent’s most famous and controversial works. Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau (1859–1915) was a famously glamorous figure in Parisian society in the early 1880s. Born in New Orleans to parents of French descent, she had immigrated to Paris as a child, later marrying a French banker in 1879 and quickly ascending the social ladder. Sargent, captivated by her arresting appearance and aiming to create a magnum opus for the Salon, convinced her to pose for him without a commission. The resulting portrait, initially shown as Madame ***, was a carefully calculated collaboration. Both artist and sitter were, in a sense, outsiders seeking prominent recognition within the competitive French capital; upon its completion, Gautreau herself described the work as a “masterpiece.”

Completed in 1884, the portrait caused a considerable stir at its premiere. Sargent had envisioned it as a bold image of a modern, self-styled celebrity. However, many viewers perceived a controversial Parisienne — or worse in some eyes, an American interloper — who dared to challenge the established manners of French society. Critics were divided; while some acknowledged its technical brilliance, many used Gautreau’s appearance to question her morals. They derided what they termed her “excessive” use of cosmetics, saw her as a symbol of vanity, and were scandalized by her “undress” — Sargent had originally painted the dress strap provocatively sliding off her right shoulder. The outcry was such that Gautreau’s mother begged Sargent to remove the portrait from the Salon. Yet, despite the uproar, Virginie Gautreau was reportedly seen in Paris just days later, defiantly wearing a low-cut dress with a similarly sparkling shoulder strap. Years later, when Sargent sold the work to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1916, he wrote that it was “the best thing I’ve done,” and requested it be titled simply “Madame X.” Today, in addition to its display of Sargent’s technical mastery, the painting serves as a fascinating reflection of societal attitudes of the era, making it an essential study in both art history and social commentary, and a prime example of the power inherent in Sargent’s portraits.

The profound impact of “El Jaleo,” another significant work stemming from Sargent’s experiences and travels during his Parisian years, was acknowledged in the exhibition. While the monumental painting itself remains in Boston, it was brought to visitors’ attention through a small text plate featuring a photographic reproduction, underscoring its historical importance. This large-scale, dramatic work, originally unveiled in 1882, depicts a Spanish flamenco dancer captured in a moment of intense performance. The oil on canvas made Sargent “the most talked-about painter in Paris” that year, a testament to its original impact.

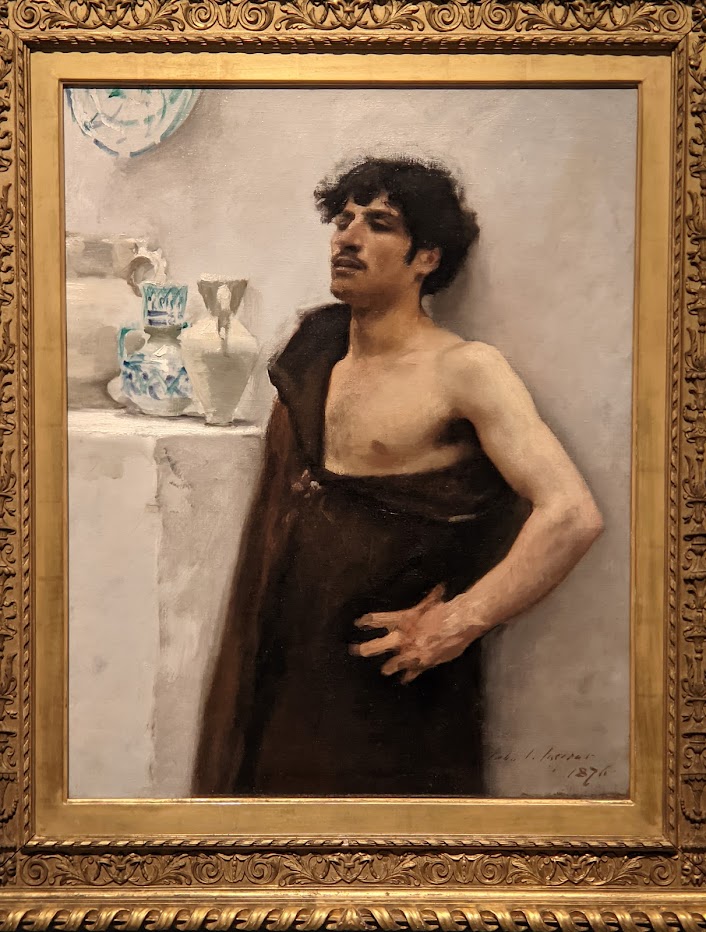

Sargent’s inspiration for such themes was fueled by his travels; he undertook an extended trip through Spain and Morocco in 1879-80. This journey included an artistic pilgrimage to Madrid, where he copied the works of Diego Velázquez at the Prado Museum, before traveling south to paint and immerse himself in the country’s vibrant music and dance traditions, eventually crossing into Morocco. “El Jaleo” brilliantly showcases Sargent’s adept handling of movement and light, alongside his deep fascination with diverse cultural themes. These explorations influenced his stylistic evolution as he ventured beyond traditional portraiture to embrace broader narratives.

The success of “El Jaleo,” along with his acclaimed flattering portrait of Charlotte Burckhardt at the 1882 Paris Salon, placed Sargent under intense pressure to deliver another extraordinary submission for the 1883 Salon. When two portraits of notable society women he had begun were not completed in time, he instead sent “The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit.”

This remarkable group portrait of the children of his friends — fellow American expatriates Edward Darley Boit and Mary Louisa Cushing of Boston — is an emotionally probing and unconventional rendering of childhood. Its carefully constructed space, employing dramatic light and shadow, is grounded in Sargent’s close study of past masters like Velázquez, as well as his keen interest in the work of contemporaries such as Edgar Degas. The result is a compellingly modern portrait that continues to fascinate viewers, showcasing the unique psychological depth found in many of Sargent’s portraits, especially those of children.

Furthermore, the exhibition’s inclusion of various drawings and travel sketches, which often served as inspiration for major paintings later exhibited in Europe and the United States, provided invaluable insight into Sargent’s creative process.

These preparatory works, often depicting subjects popular at the time such as local people, distinct architecture, and evocative seascapes, highlight his evolving techniques and his remarkable ability to convey emotion with elegance and precision. Even early in his career, upon completion of his formal training, Sargent demonstrated his ambition by showing two paintings at the Salon in 1878: a landscape painted in Capri and a portrait of his teacher Carolus-Duran. The latter earned an honorable mention, with some critics even suggesting the student had surpassed his master. Sargent was consistently drawn to the unique quality of Mediterranean light. On several major painting trips, he skillfully captured the distinct characteristics of each locale, including picturesque sites, vernacular architecture, and local inhabitants, though these works were sometimes shaped by his quest for subjects that Western audiences of the time considered “exotic.” During extended visits to Venice in 1880 and 1882, for instance, he chose to paint unusual, less-traveled vistas, far from the typical tourist gaze.

The 2025 exhibition also thoughtfully featured a selection of captivating works that highlight Sargent’s diverse artistic explorations, such as the exotic “Smoke of Ambergris” (Fumée d’ambre gris), which immerses viewers in a mysterious, incense-filled scene (below right), and his vibrant depiction of the Spanish dancer “La Carmencita.”

These pieces not only highlight Sargent’s exceptional talent and versatility — from enigmatic genre scenes to dazzling performance portraits — but also showcase his engagement with diverse cultural inspirations. Through such a comprehensive collection, the exhibition vividly illustrated Sargent’s profound influence on the art of portraiture and figure painting, solidifying his enduring legacy. Indeed, understanding Sargent and Paris during this formative period is key to appreciating his launch as his era’s “greatest contemporary portrait painter.”

Thematic Elements and Artistic Techniques

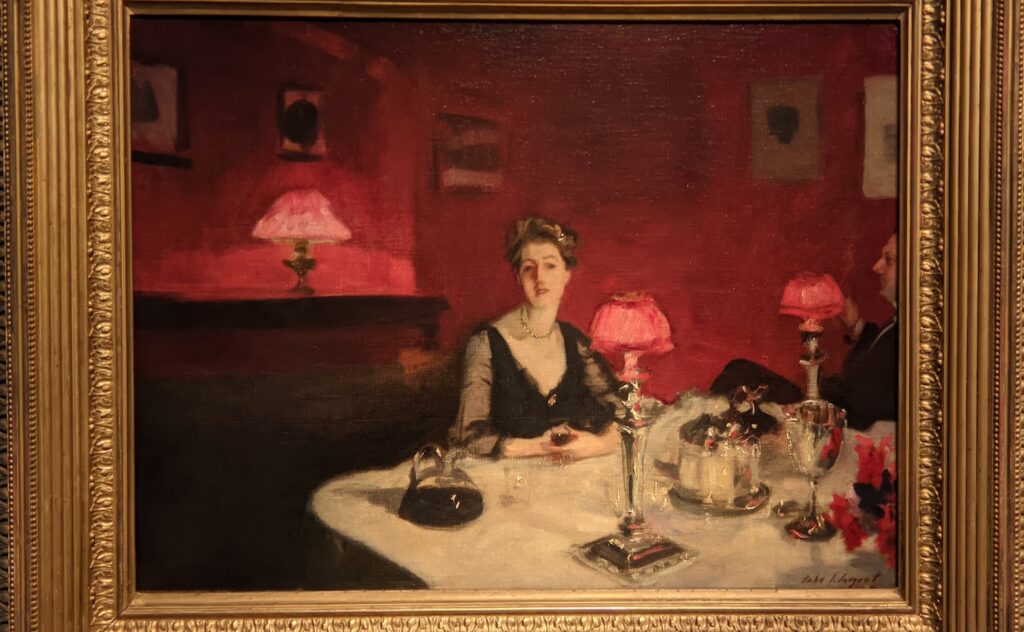

The “Sargent and Paris” exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art offered a profound exploration of thematic elements and artistic techniques that not only define Sargent’s unique style but also resonate deeply with the prevailing art movements of his time, particularly Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Sargent’s work from this period is often characterized by its brilliant, luminescent use of light and color, masterfully employed to create both vibrancy and depth in his paintings. His fluid application of paint, sometimes akin to the Impressionist techniques of his contemporaries, reveals his exceptional ability to capture the transient effects of light, thereby evoking a sense of immediacy and strong emotional resonance in the viewer.

Sargent’s success in Paris was not solely reliant on his technical skill; he also built a significant social and professional network through his innate talent, keen intellectual curiosity, and considerable social acumen. He moved fluidly and confidently among sophisticated circles of artists, writers, and influential patrons. Described as a charismatic companion, his congeniality and good humor were qualities that served him well, especially during the often lengthy and demanding hours required for portrait sittings. The novelist Henry James, a contemporary and friend, aptly wrote of Sargent, “His character is charmingly naif, but not his talent.” Further bolstering his reputation, Sargent was well acquainted with many prominent literary figures and art critics of the day, such as Louis de Fourcaud and Emma Allouard-Jouan, who penned astute critiques of his art for prestigious journals. Many of the portraits featured in this gallery bear witness to Sargent’s close relationships with these influential figures. He often created dashing, insightful portraits of his friends as tokens of appreciation, frequently employing a more experimental style suited to their progressive and cultured tastes.

His compositions, particularly his portraiture, frequently reflect a profound connection to his subjects. Through the careful and strategic consideration of light and shadow, Sargent elevated the human experience, rendering his figures with an almost sculptural quality that gave them presence and vitality. Sargent’s portraits were far more than mere documentations of appearance; they delved deeply into the essence of individual character, often simultaneously portraying the intricate social dynamics and rich cultural contexts of Parisian life. This focus on societal interactions is highly emblematic of the prevailing social currents of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period when traditional notions of personal identity and societal roles were undergoing dramatic shifts. During these formative years, Sargent’s career as a portraitist flourished. He shrewdly catered to an upwardly mobile international clientele, quickly becoming known as a flattering and insightful painter of women. The close friendships he formed with many dynamic women of Paris — from artistic, literary, and high society circles — were essential to his success and serve as a testament to his proximity to the city’s vibrant social and cultural epicenter.

A key figure embodying this Parisian ideal of modern femininity was the “Parisienne.” As described in the exhibition, in the second half of the nineteenth century, this fashionable, modern woman of Paris became a captivating fascination, not only within French society but also quickly spreading abroad. She was seen to encapsulate a particular worldly elegance and sophisticated chic that was considered unique to the denizens of the capital.

This mythic ideal, sometimes poetically described as having “arisen like Venus from the waters of the Seine,” was a potent source of national pride and a recurring figure in popular culture, including stage plays, newspapers, and satirical cartoons. Artists of the era keenly competed on the walls of public art exhibitions to express the Parisienne’s “ineffable chic.” This artistic interest existed alongside a certain societal anxiety about foreign threats to French cultural superiority, leading to fervent debates about what constituted a “true Parisienne” and whether one had to be French to embody this ideal. The exhibition thoughtfully includes six portraits of Parisiennes by various artists whom Sargent would have known and admired. These works, ranging from conservative to progressive in style, showcase diverse interpretations of modern beauty. Sargent himself, acutely aware of this popular and complex subject, navigated these currents as he sought to satisfy his sitters while simultaneously distinguishing his own art from that of his competitors.

The themes of society and the multifaceted human experience are further emphasized in Sargent’s landscapes and genre scenes. In these works, he often employs a rich, nuanced palette to reflect the vibrancy and dynamism of Parisian life. The elusiveness of time, a common motif in Impressionism, is also evident in Sargent’s work, as he subtly invites the viewer to consider both the fleeting moment captured on canvas and the broader, ongoing narrative of life that unfolds in the bustling city. By examining these intricate thematic connections and Sargent’s distinct artistic techniques, one gains a far more comprehensive understanding of his significant contributions to the evolving art scene in Paris, a body of work that masterfully bridged tradition and modernity in an innovative manner. Sargent’s mastery not only exemplifies his artistic brilliance but also perfectly encapsulates the essence of a transformative and exhilarating period in art history, a narrative expertly explored throughout the “Sargent and Paris” exhibition.

Visitor Insights and Experience at the Met

The “Sargent and Paris” exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art clearly garnered significant attention by creating an engaging and thought-provoking atmosphere for both seasoned art aficionados and casual visitors alike. For more information about art on display at the Met and other museums in New York, please visit our other articles: New York City — 4 of the Best Art Museums and New York City — Fashionable Exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum and the museum’s website.

Additional Images From the “Sargent and Paris” Exhibition

“Sargent and Paris” Was on Display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art & the Musée d’Orsay During 2025