The Best of Boston — Gauguin, Monet & Sargent

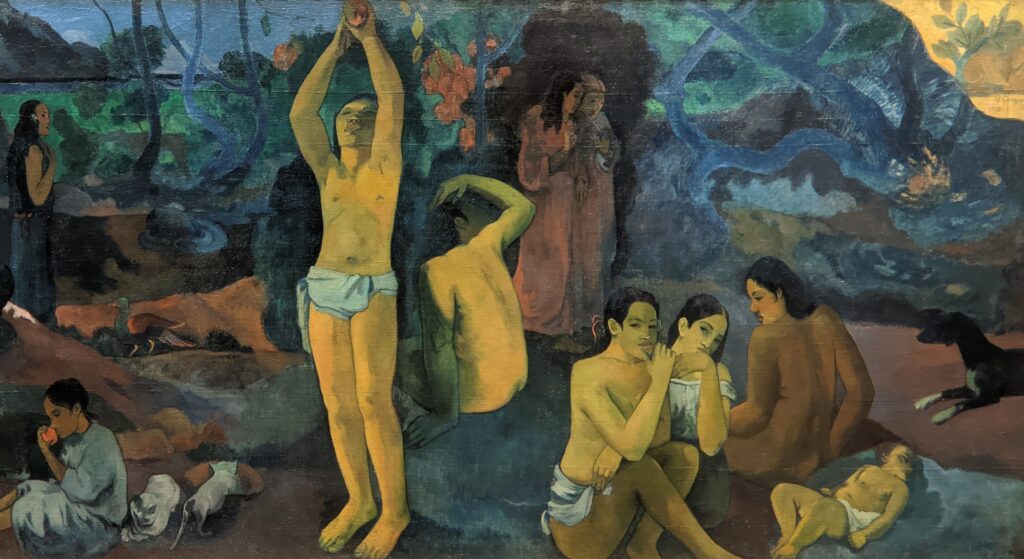

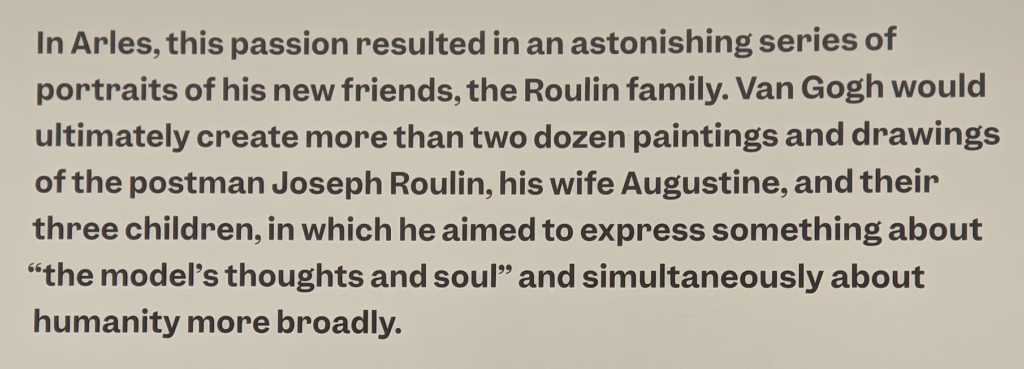

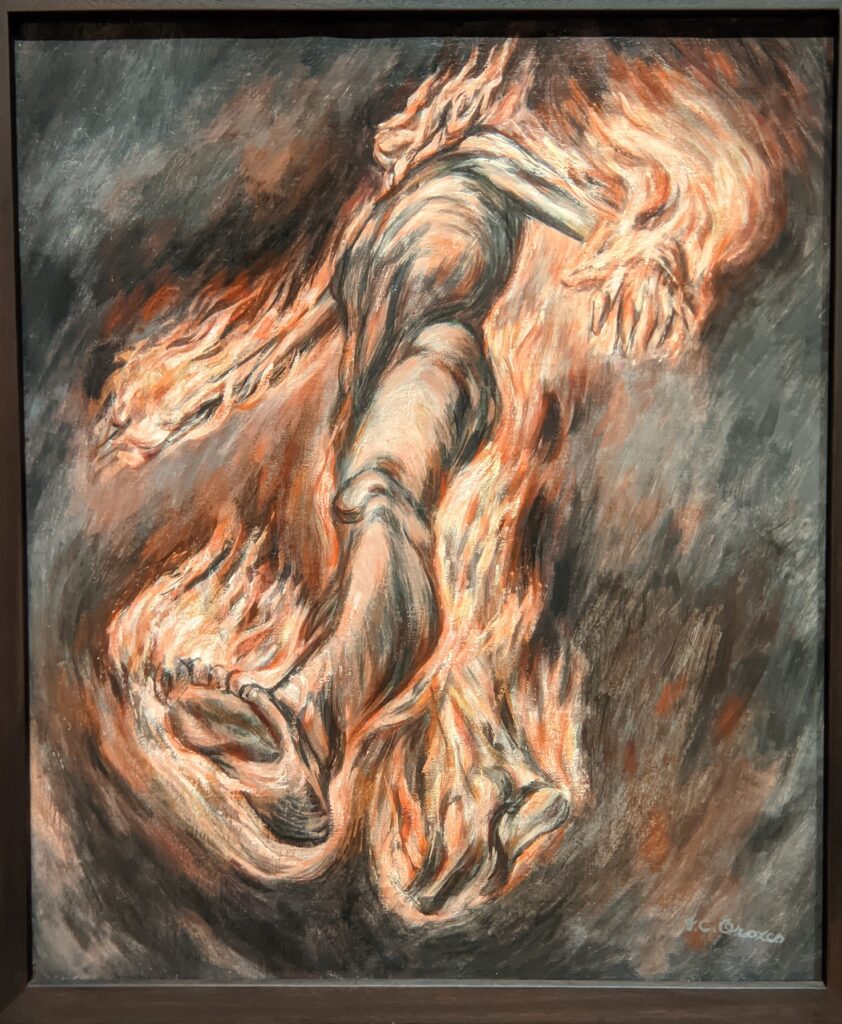

When travelers tell us they plan to spend a week in New York, our initial response is to suggest that a 10-day visit to Boston and New York City would be ideal. For art lovers, Boston is a relaxed place to contemplate “Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?”, the monumental mural Paul Gauguin painted on heavy burlap in Tahiti between 1897 and 1898.

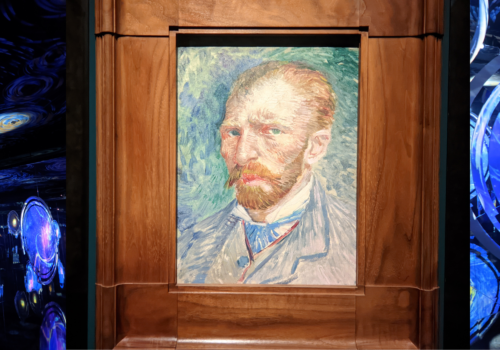

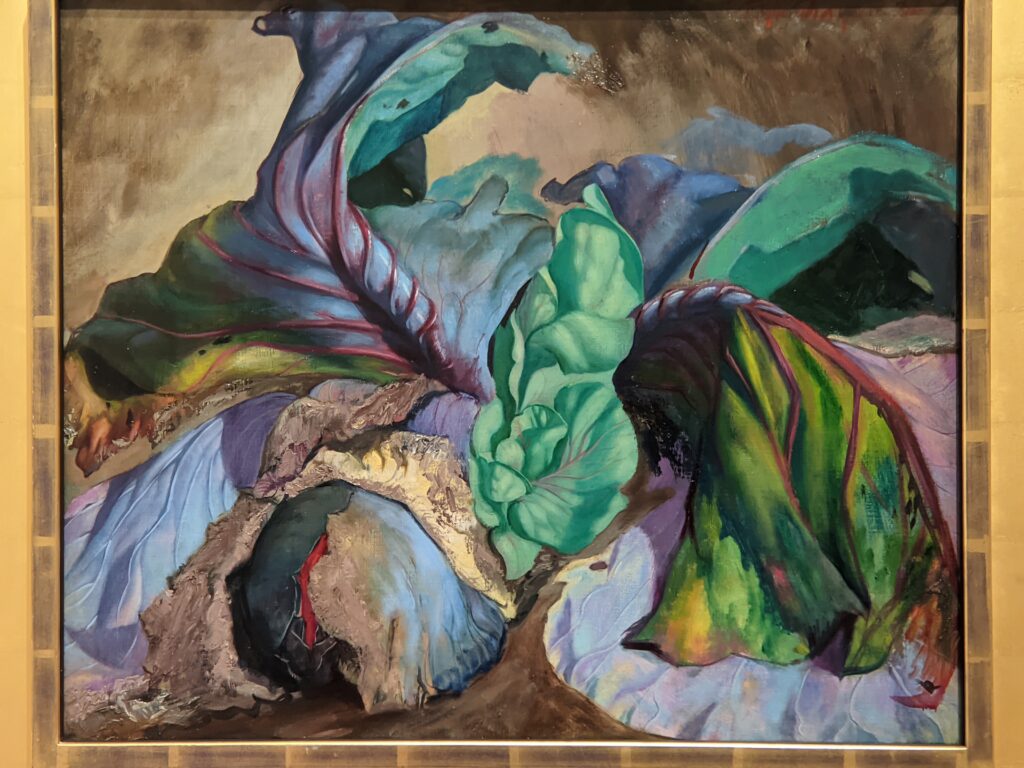

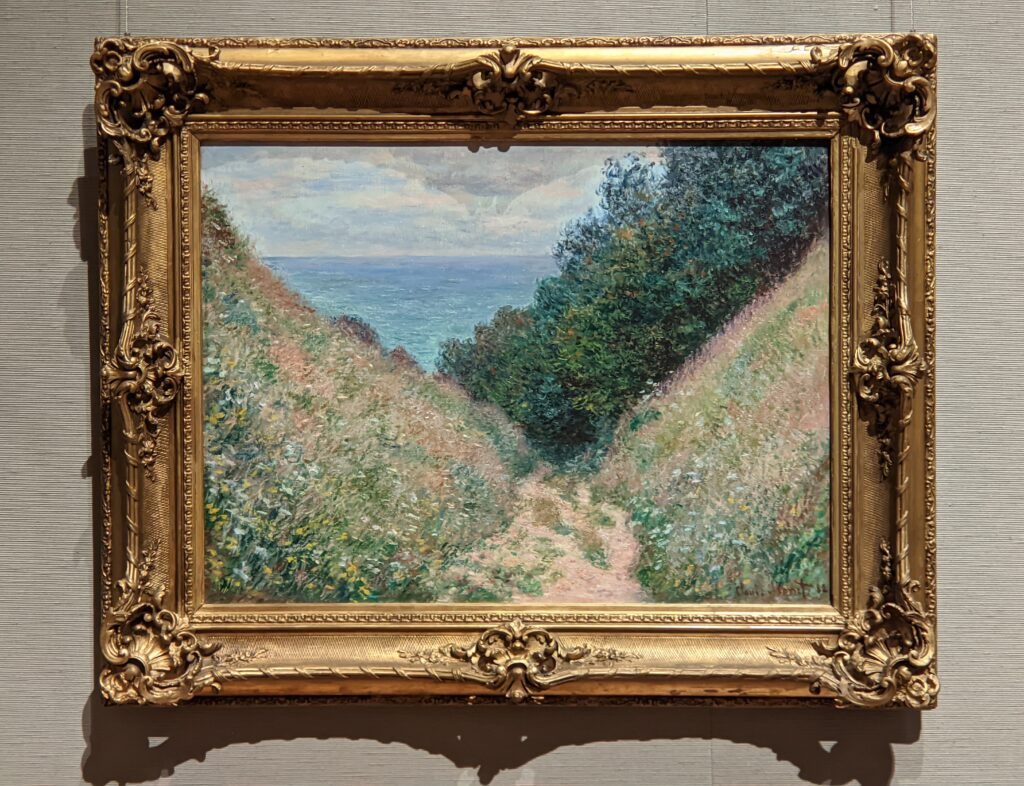

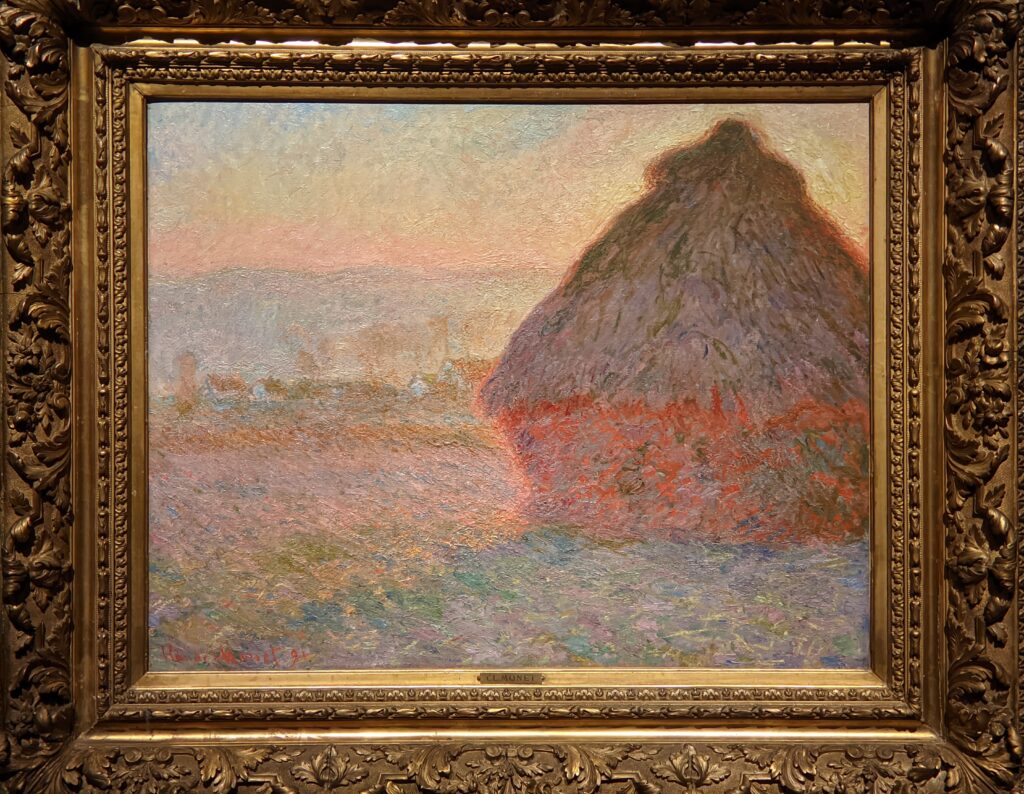

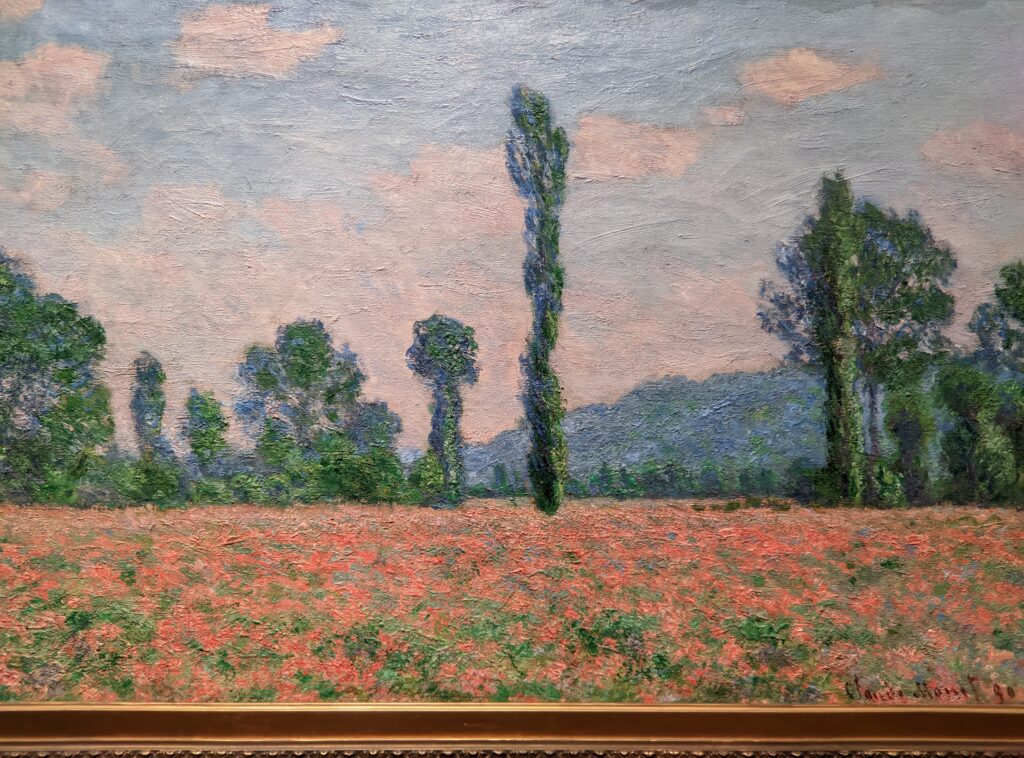

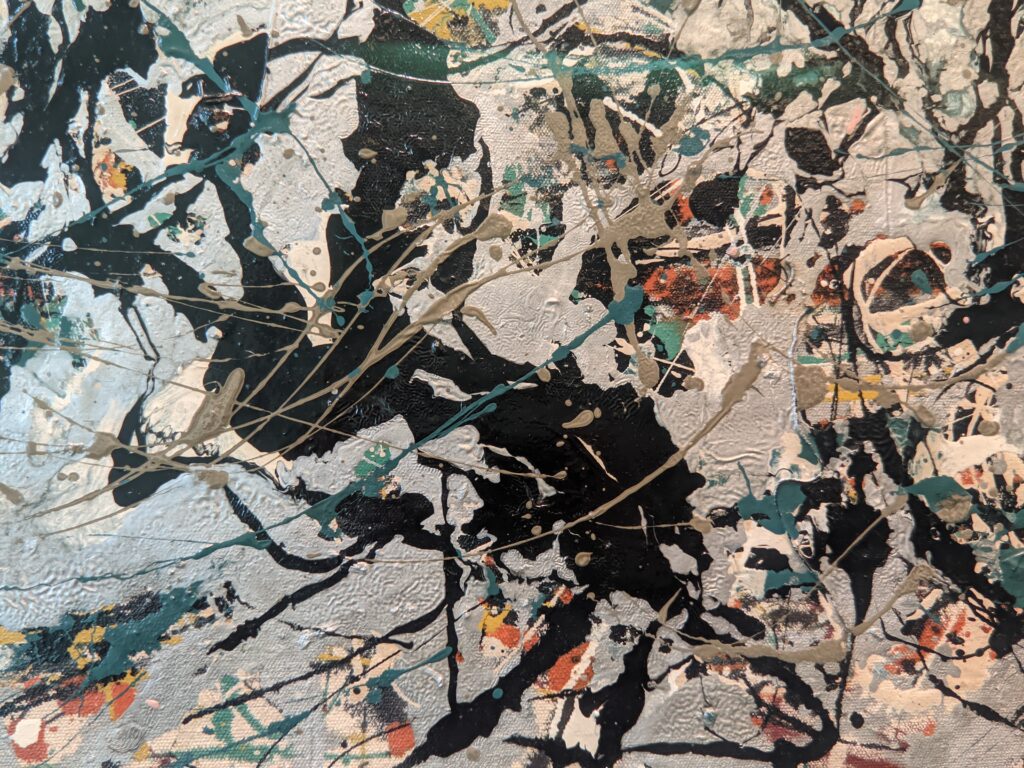

Gauguin’s Tahitian masterpiece “Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?” (detail above) is displayed among other iconic works of art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which also owns 35 oil paintings by Claude Monet (below) and the world’s most comprehensive collection of John Singer Sargent’s oeuvre.

The Winslow Homer WATERCOLOR Exhibit Closed on January 19, 2026

IF YOU MISSED THE HOMER, VINCENT VAN GOGH & GEORGIA O’KEEFFE EXHIBITIONS DURING 2025 — WE HAVE HIGHLIGHTS FOR YOU IN THIS ARTICLE

Van Gogh’s “Roulin Family Portraits” Closed in September 2025

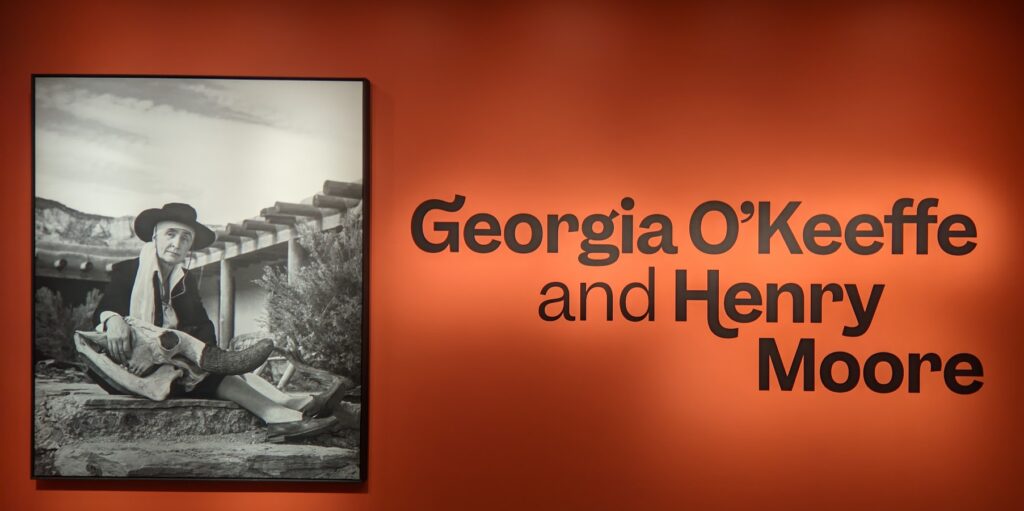

In our section devoted to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (below), you will see distinctive and personal paintings by Winslow Homer and Van Gogh, as well as highlights from previous iconic exhibits devoted to Rachel Ruysch, John Singer Sargent, Salvador Dalí, Georgia O’Keeffe and Henry Moore.

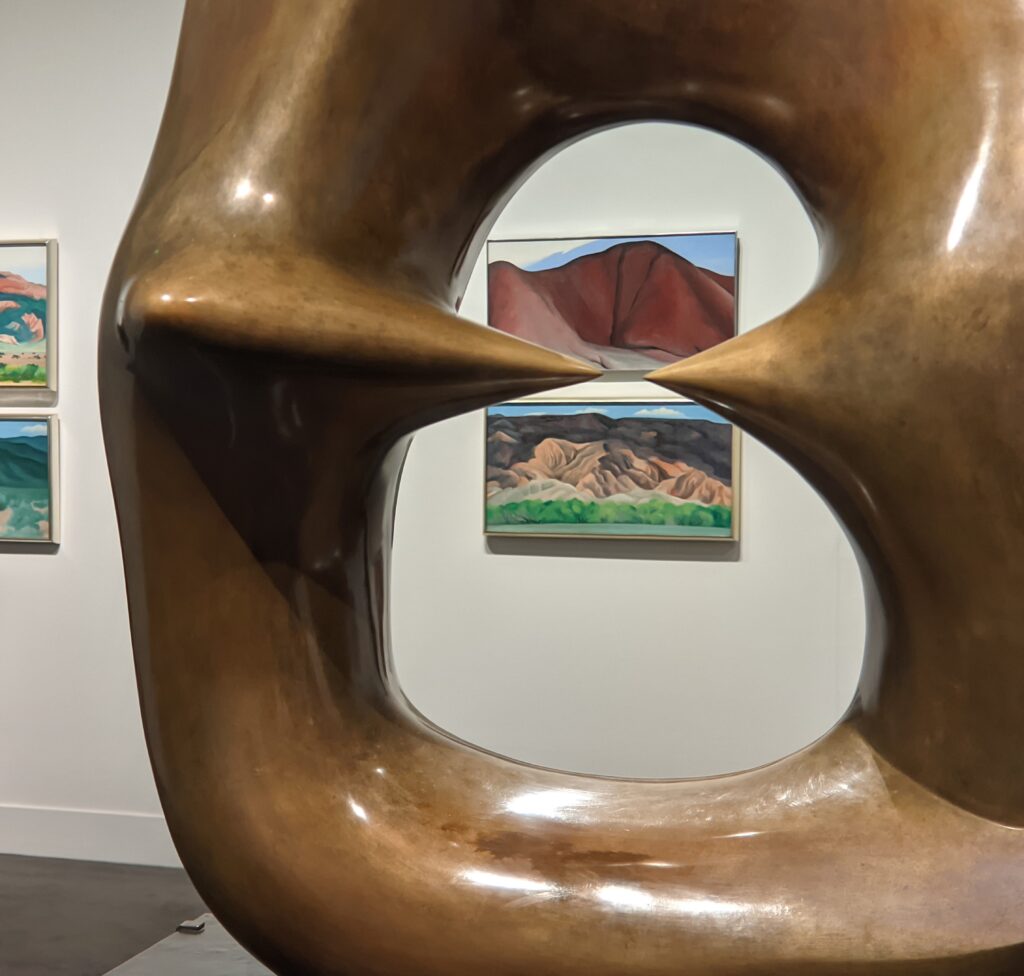

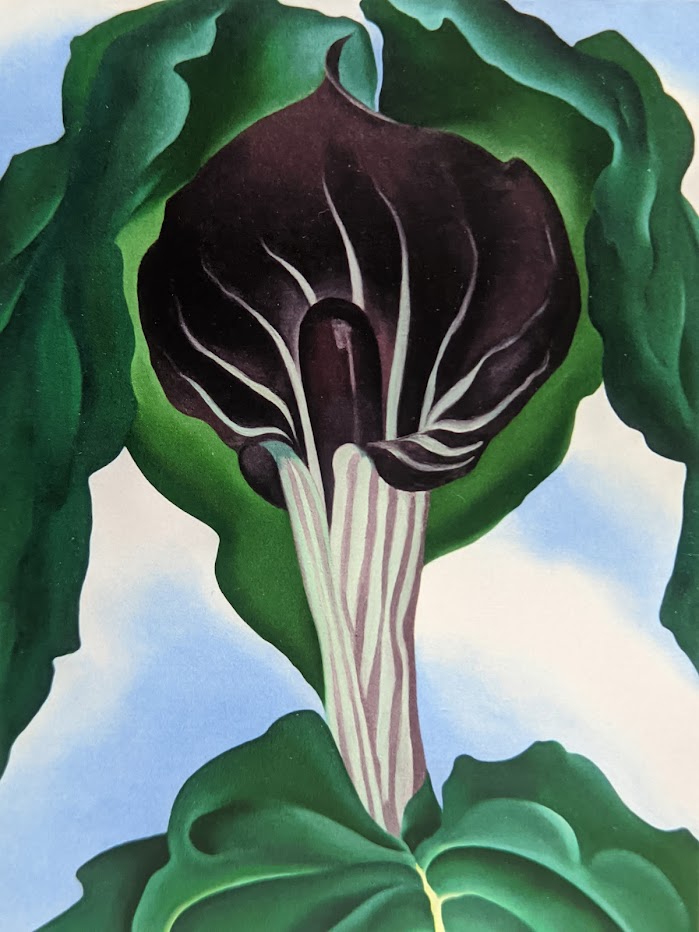

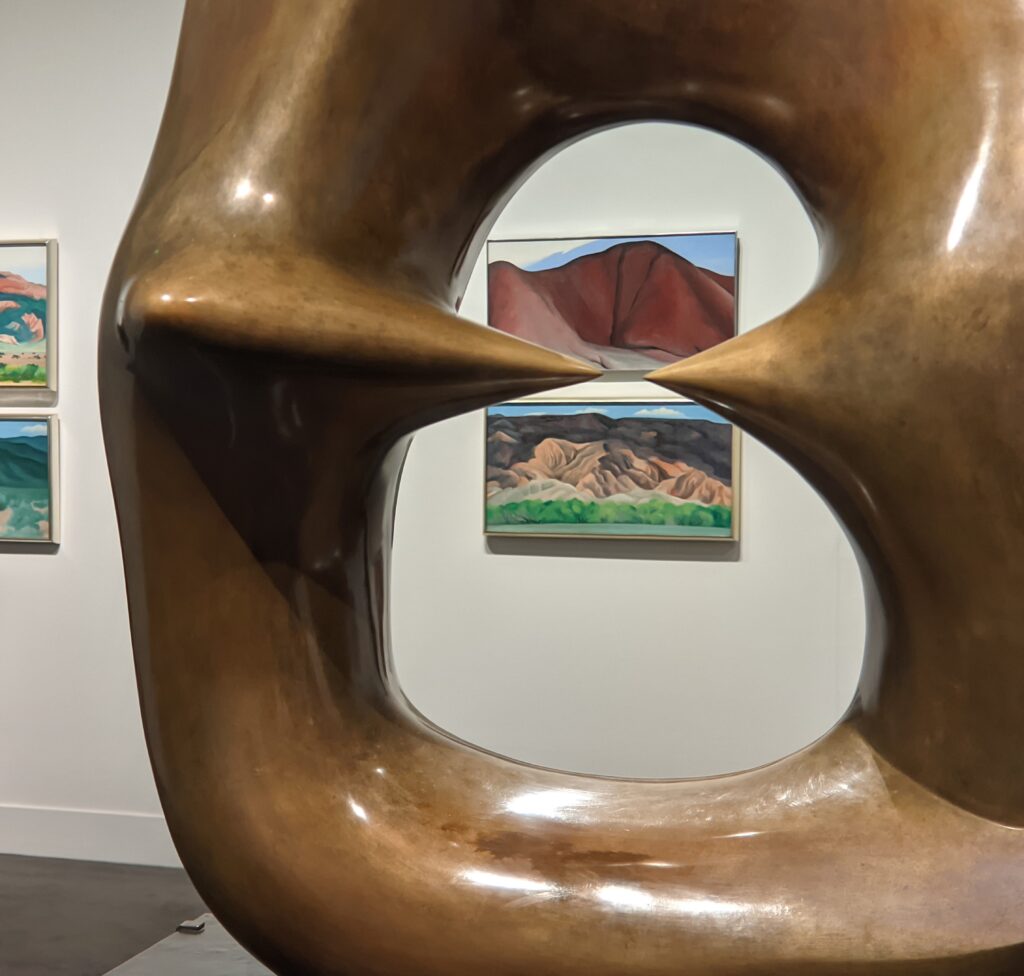

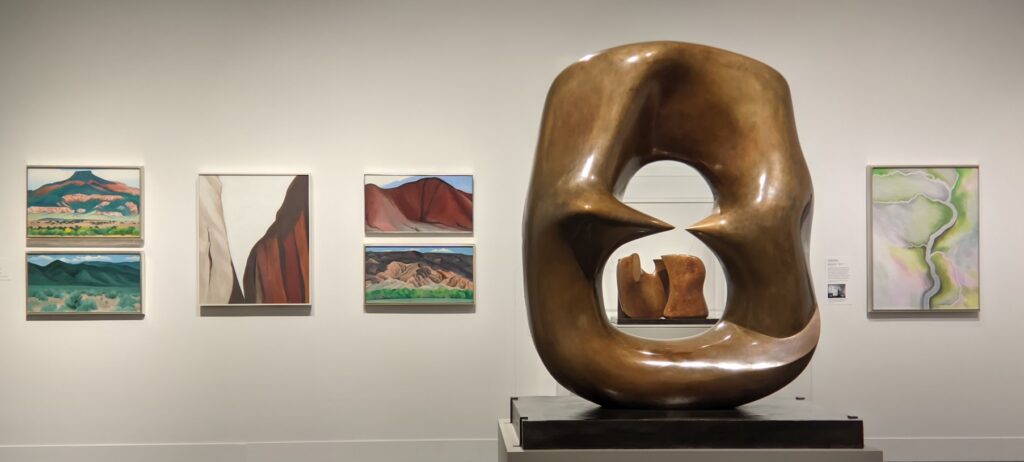

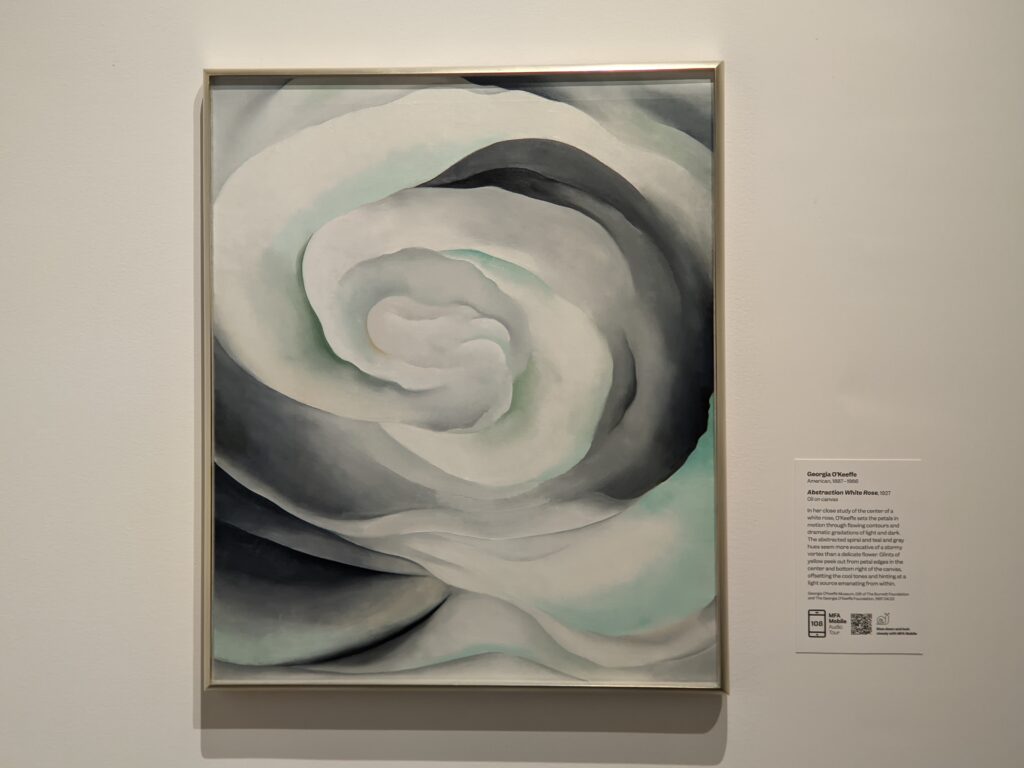

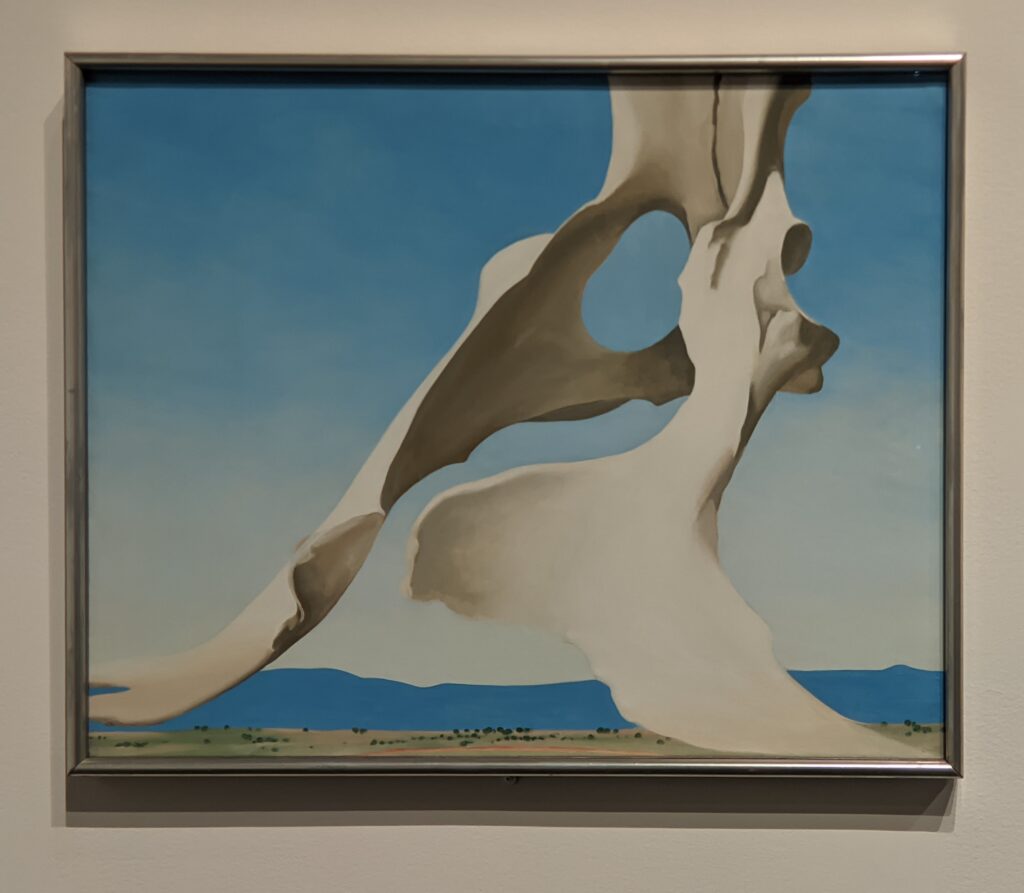

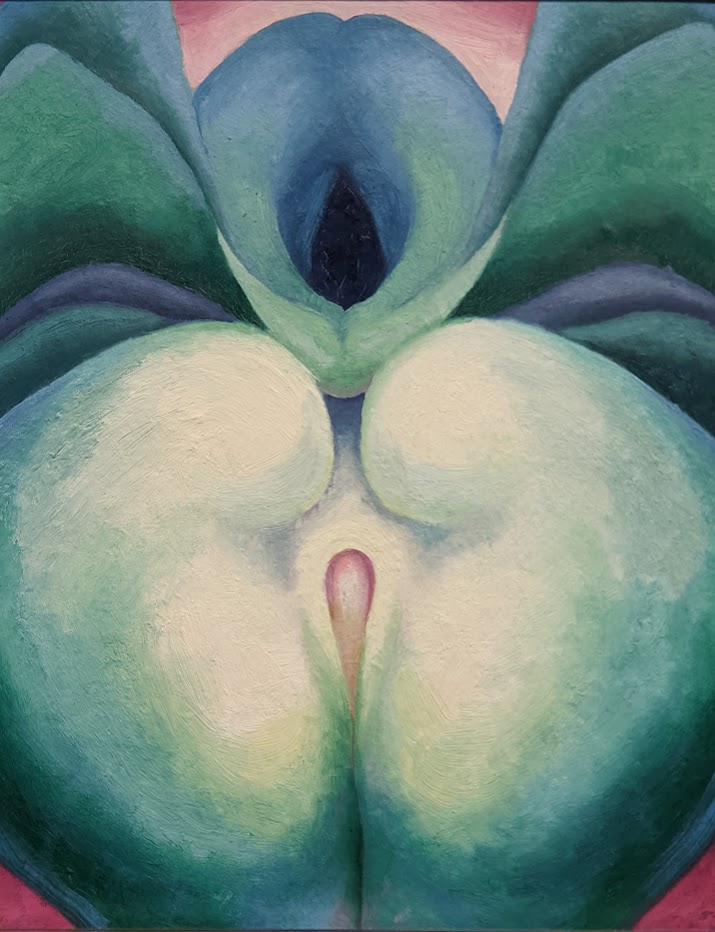

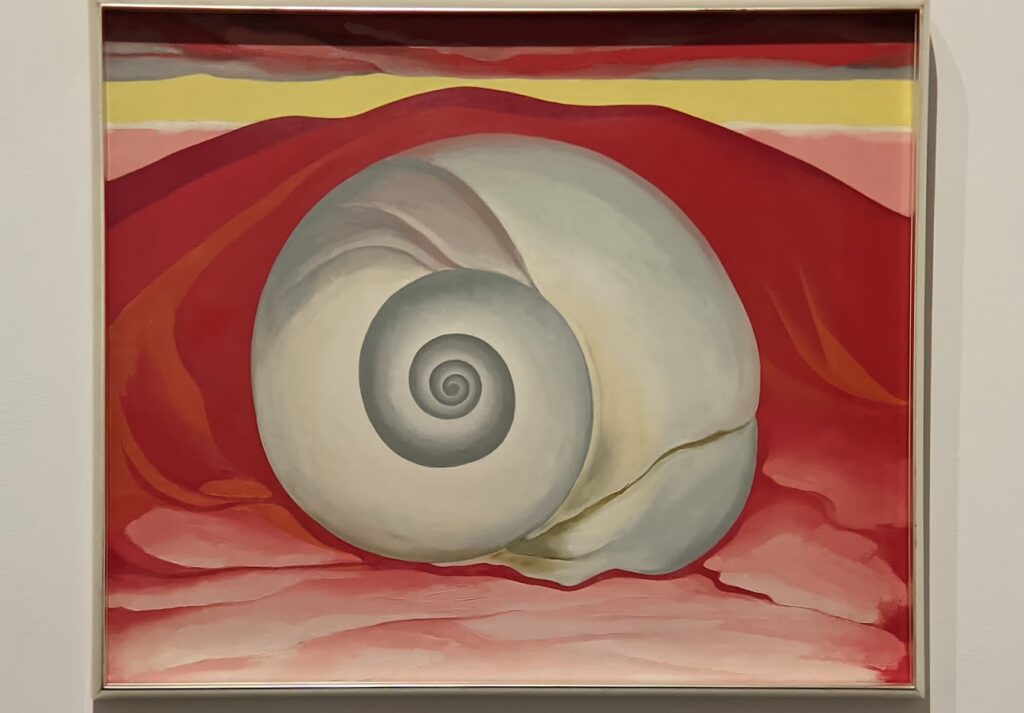

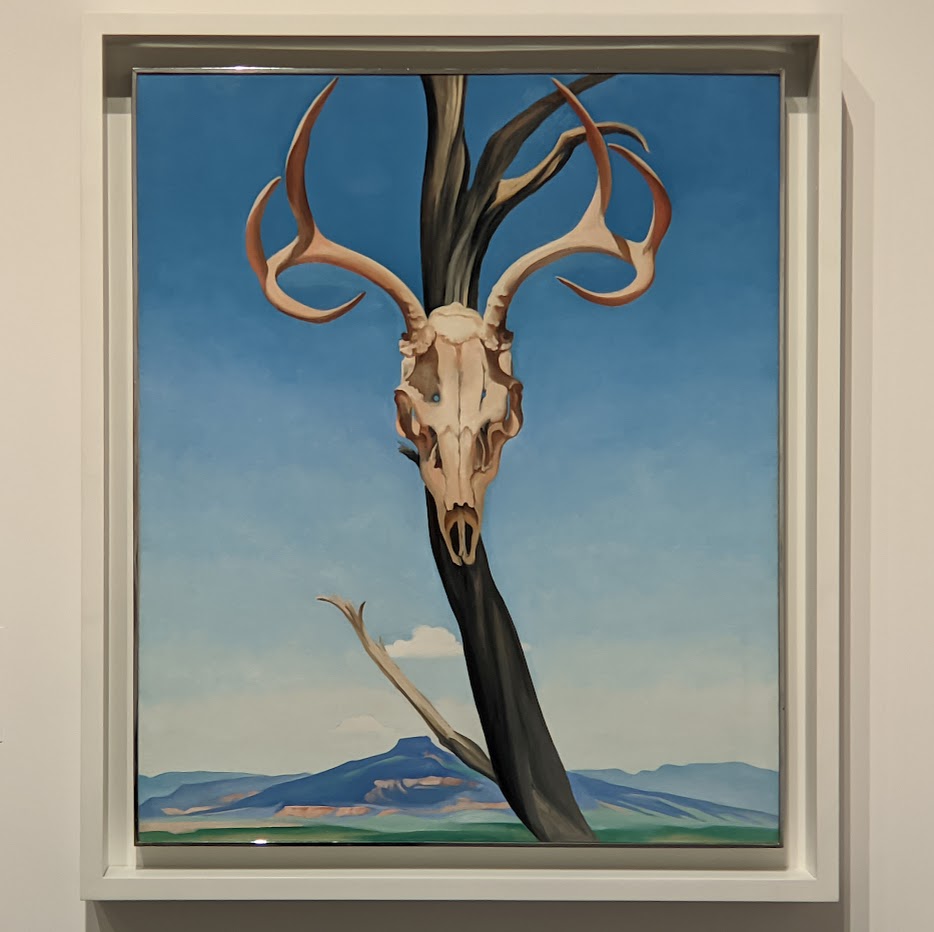

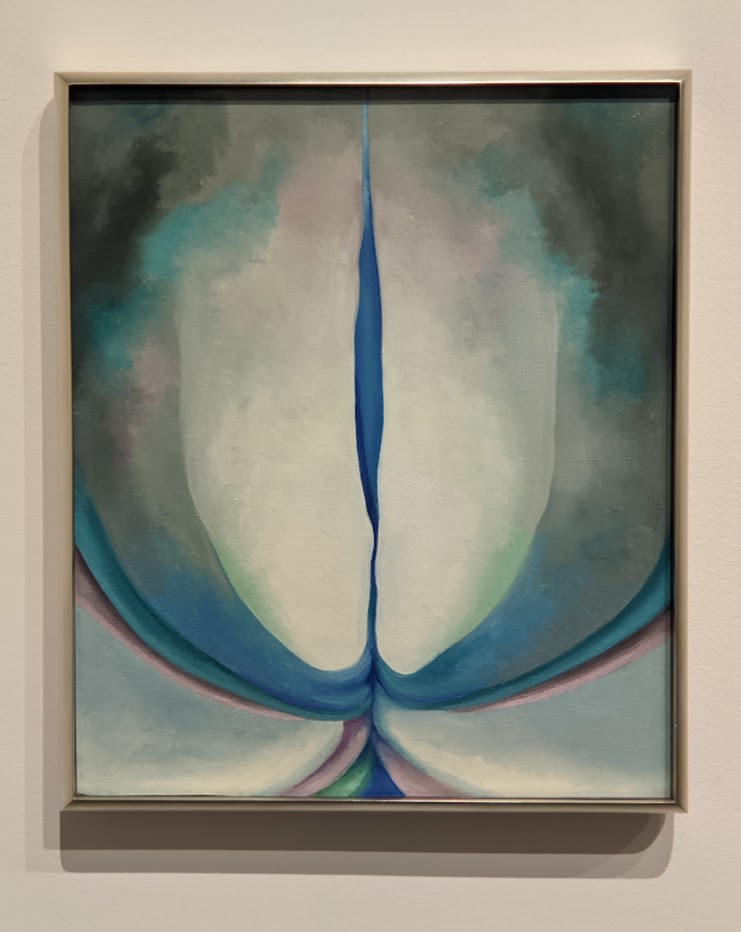

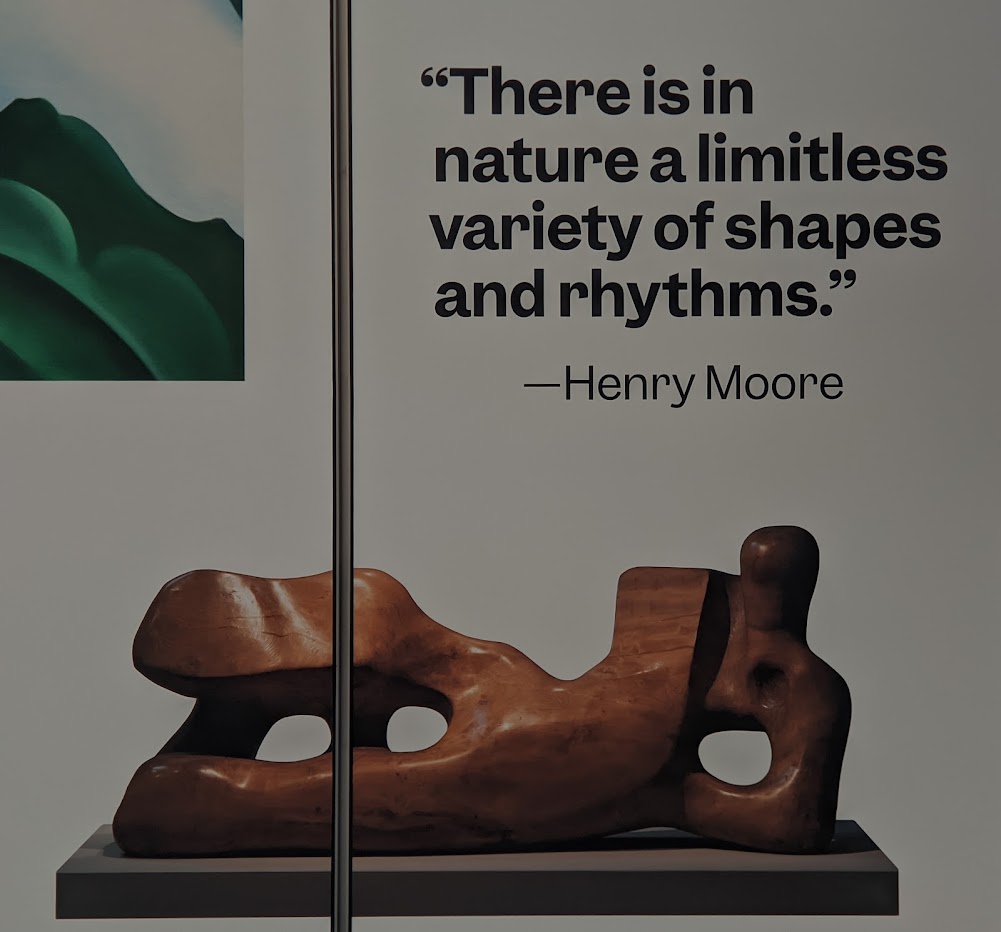

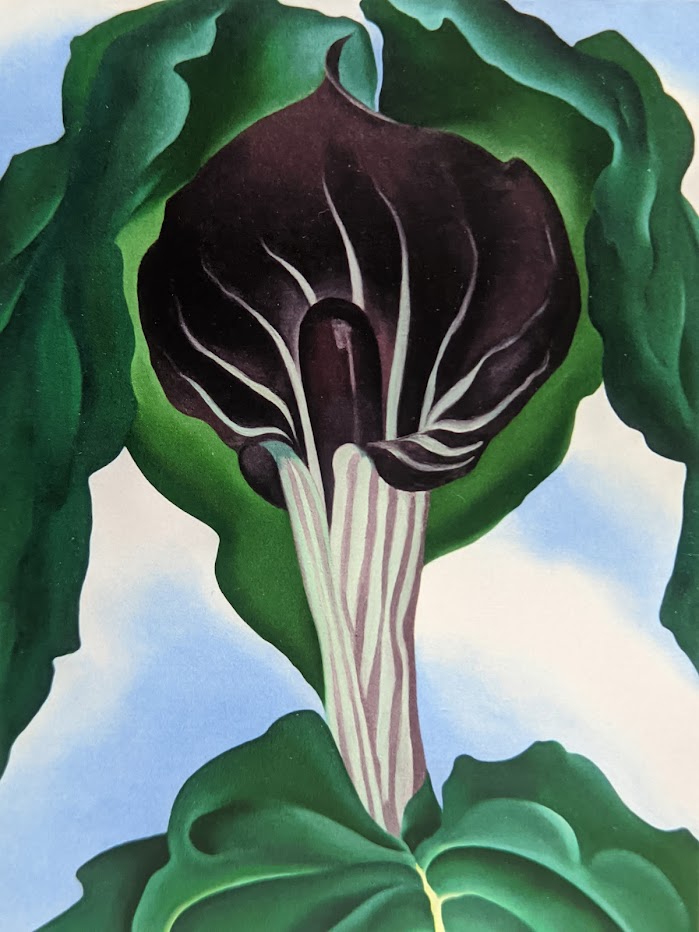

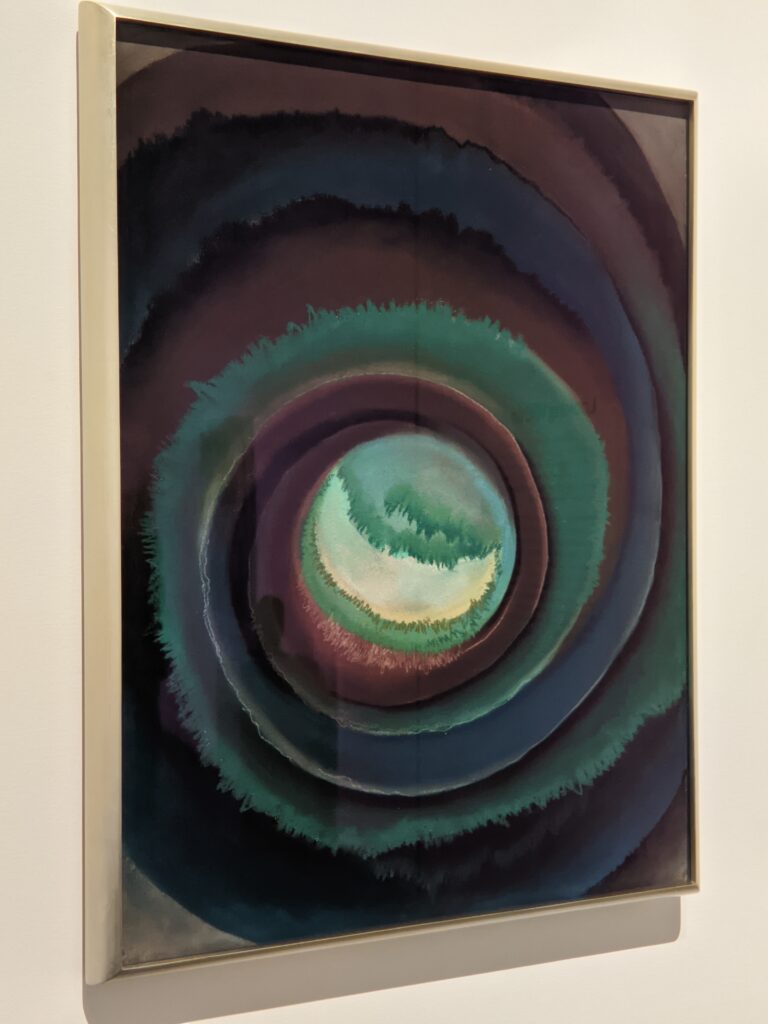

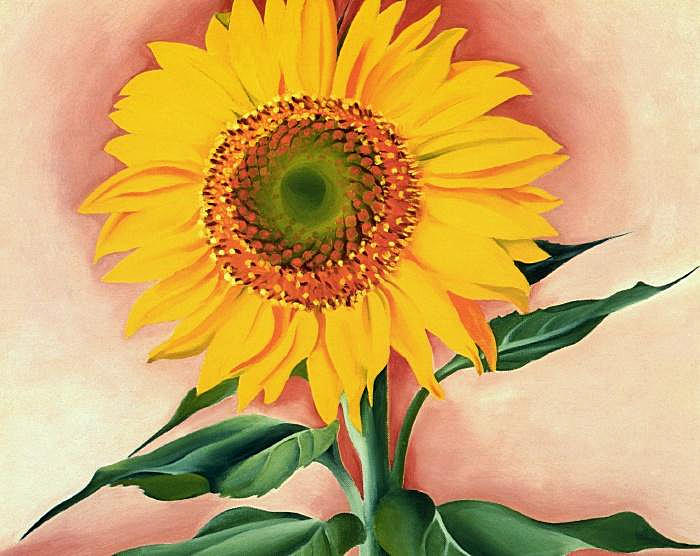

O’Keeffe and Moore turned nature into art. How they re-imagined natural forms into modern art was the subject of an exhibit which opened in 2024 and closed in 2025 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. More than 50 images from this unique pairing of these two giants of abstract modernism appear later on in this article.

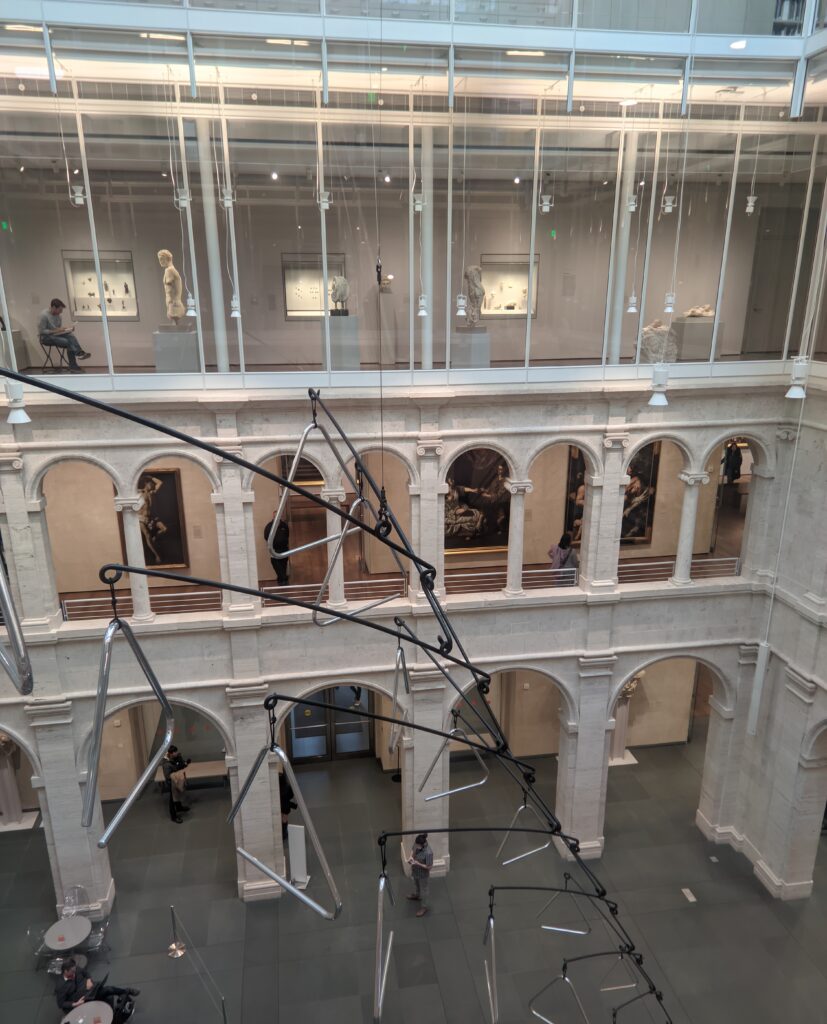

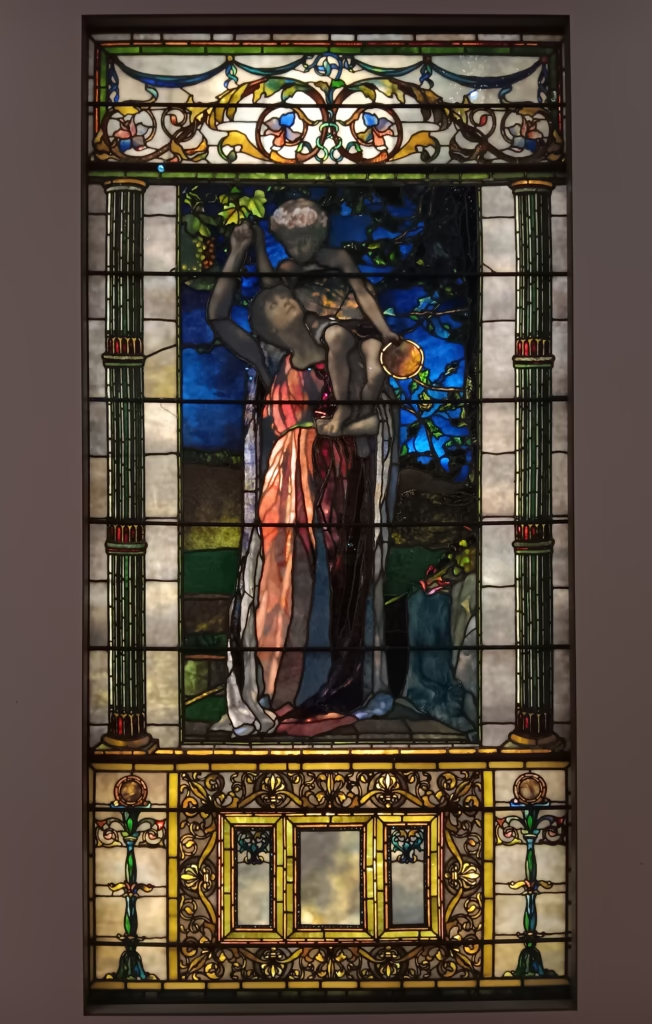

Founded in 1870, the Museum of Fine Arts moved in 1909 to its present location near the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum — a fine example of Venetian Gothic Revival architecture with an enchanting glass-covered garden courtyard (pictured below), the first of its kind in the United States.

Boston

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

In the 1890s, Isabella and John Gardner realized that their home on Beacon Street in Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood was too small to house their growing collection of art, which included Fra Angelico’s “Assumption and Dormition of the Virgin” (below left), paintings by Botticelli, Titian, Velázquez and Sargent, and a drawing by Michelangelo. Following John’s death in 1898, Isabella purchased land in the marshy Fenway area to realize the couple’s shared dream of building a museum to house their art treasures. The museum (below right) was completed in 1901 in the style of a 15th-century Venetian palace and opened to the public two years later. 13 artworks (including Vermeer’s “The Concert” and Rembrandt’s only known seascape, “The Storm on the Sea of Galilee”) were stolen from the Gardner Museum in 1990. A $10 million reward remains in place for information leading to the recovery of the art, as this crime remains unsolved.

“Isabella Stewart Gardner constructed her art museum to center horticulture as a ‘living art,’ placing the blooming Courtyard at the heart of her galleries and cultivating numerous species of plants to establish a living collection that still exists today,” according to the Gardner’s website.

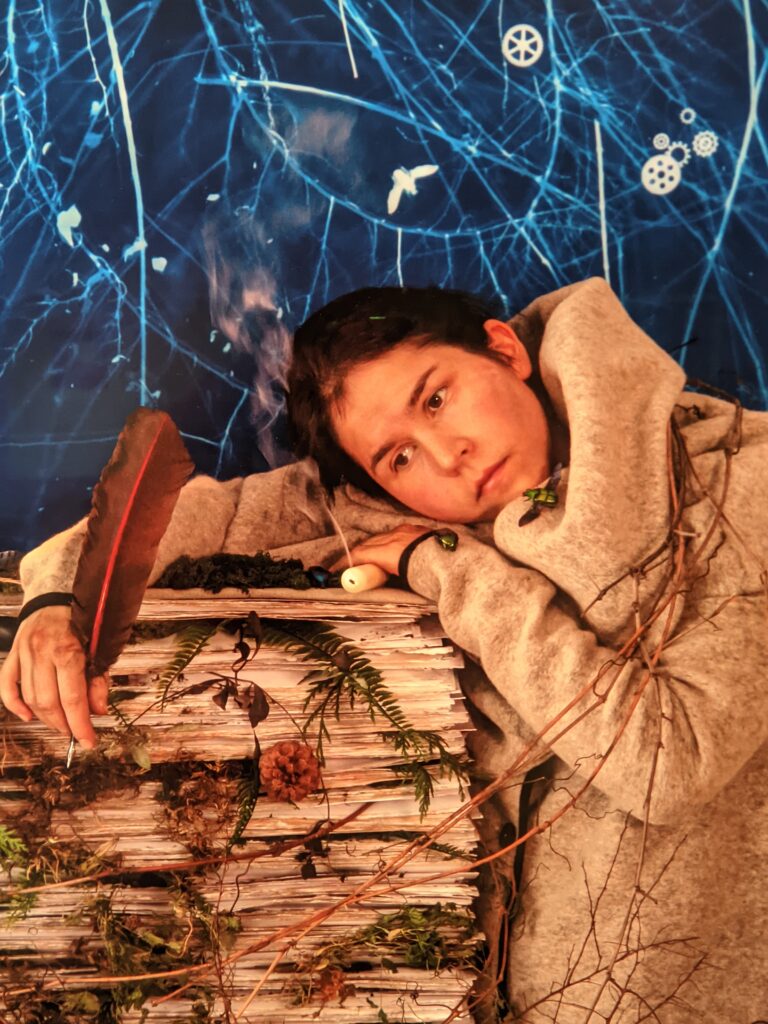

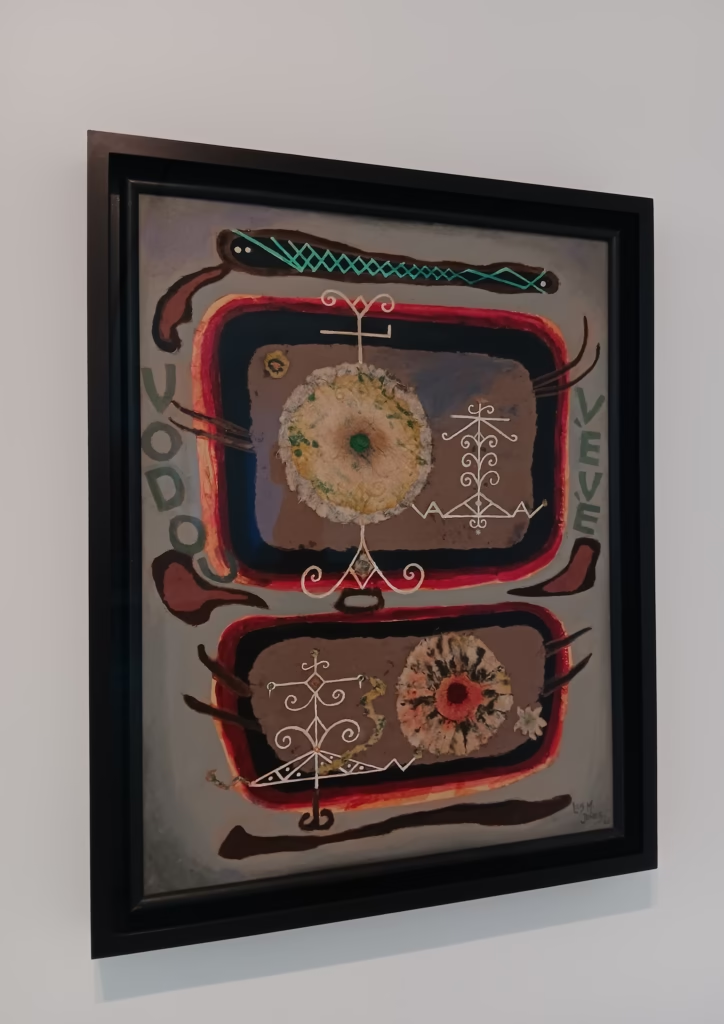

The Gardner also hosts small, temporary exhibitions. If you missed “Waters of the Abyss” by the Haitian artist Fabiola Jean-Louis or “Manet: A Model Family” (image above), which closed in 2025, you should definitely check the Gardner’s website for information regarding current and upcoming shows, plus free entry to the museum from 3:00 until 9:00 p.m. on the First Thursday of each month.

Boston Public Library

The Public Library opened in 1854, and the Central Library’s McKim Building (an architectural masterpiece in Copley Square opposite Trinity Church) was completed in 1895. Art lovers are drawn to this Back Bay neighborhood to see murals created by the American Edwin Austin Abbey and the Frenchman Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. John Singer Sargent, born in Italy to an American family, felt close ties to Boston and spent 29 years painting mural panels that adorn the Sargent Gallery inside the Boston Public Library. While Sargent considered this commission an opportunity to create a masterwork, the final central panel along the East Wall (intended to illustrate the Sermon on the Mount) was never completed and remains blank to this day.

Cambridge Lies Across the River from Boston

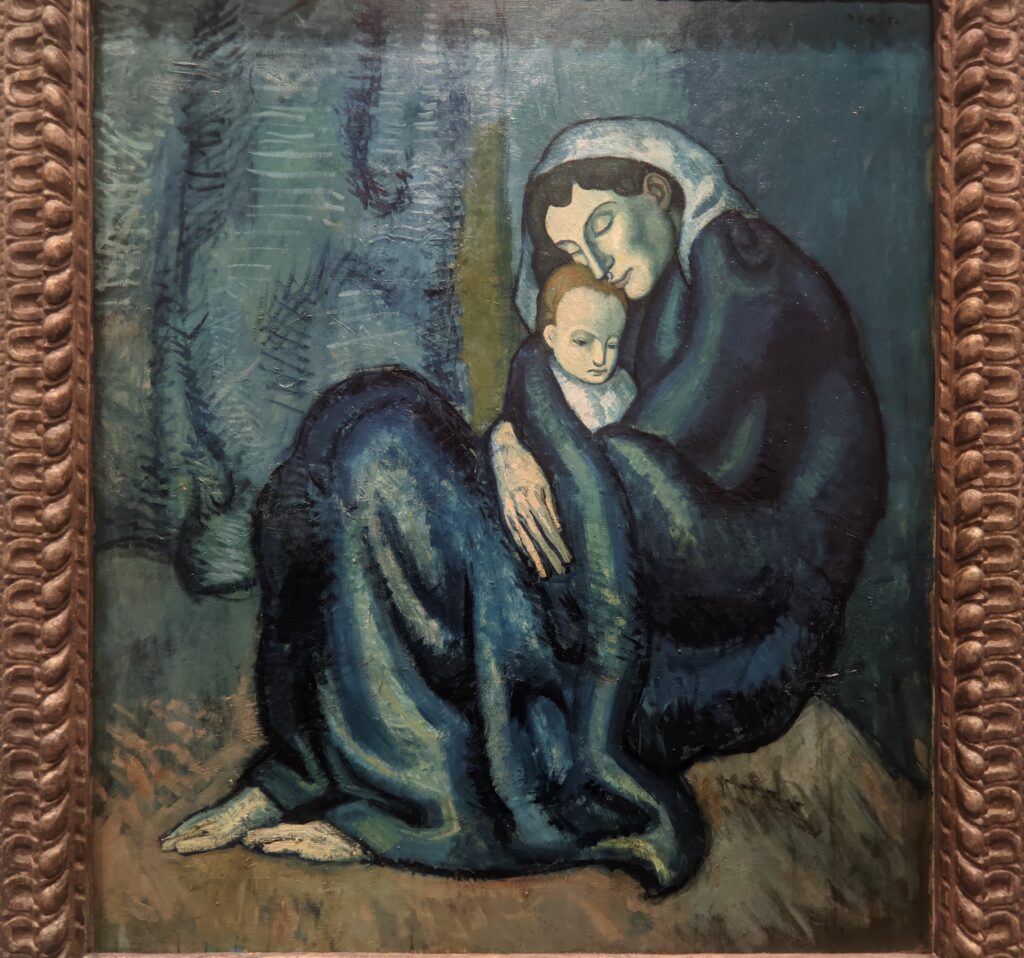

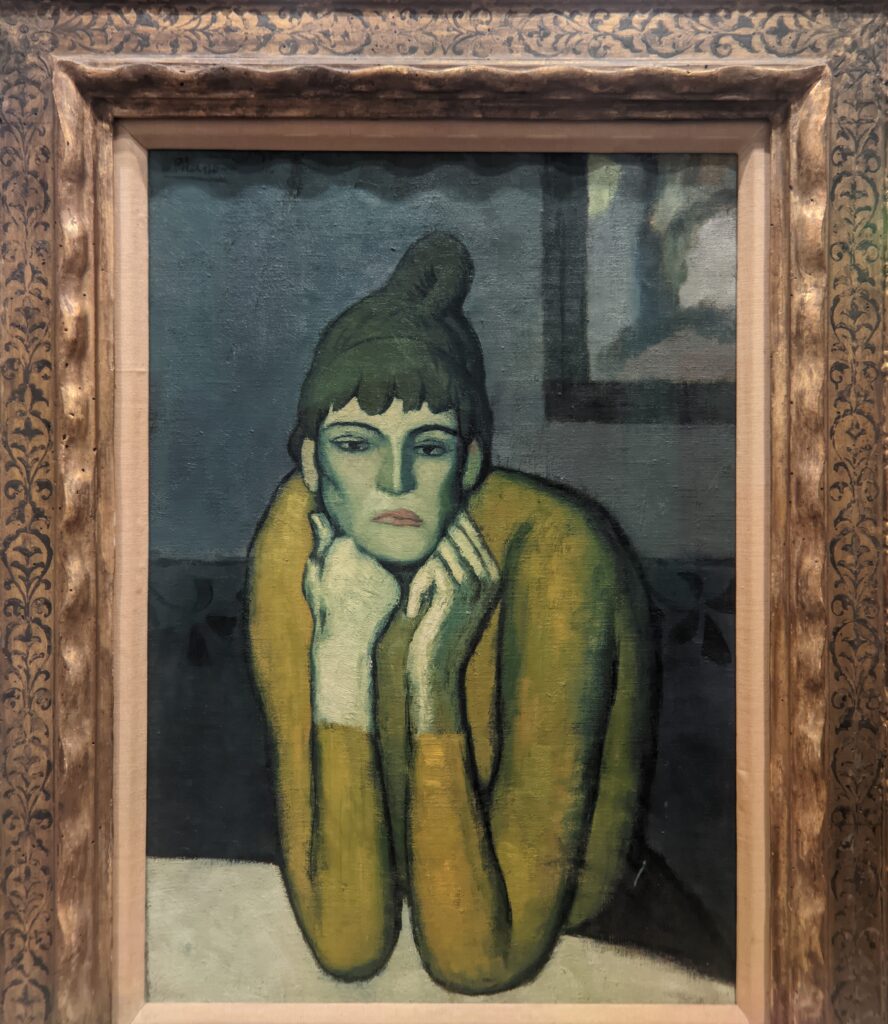

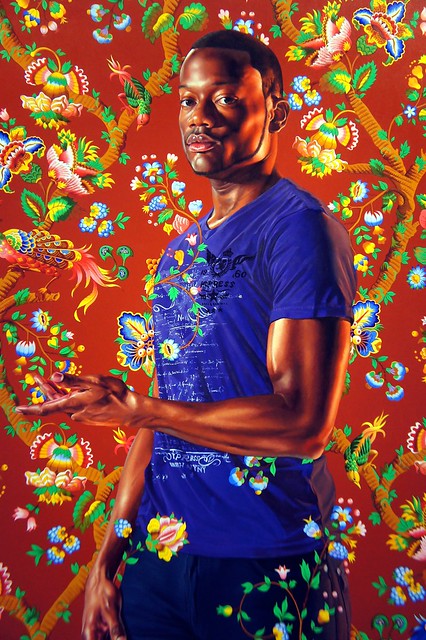

Cambridge, on the other side of the Charles River from Boston, offers amazing portraits by the greatest painters from the 17th- through the 20th-century, including Van Gogh and Picasso (above), inside the Harvard Art Museums.

Harvard Art Museums

The Harvard Art Museums Are Now Free for All Visitors

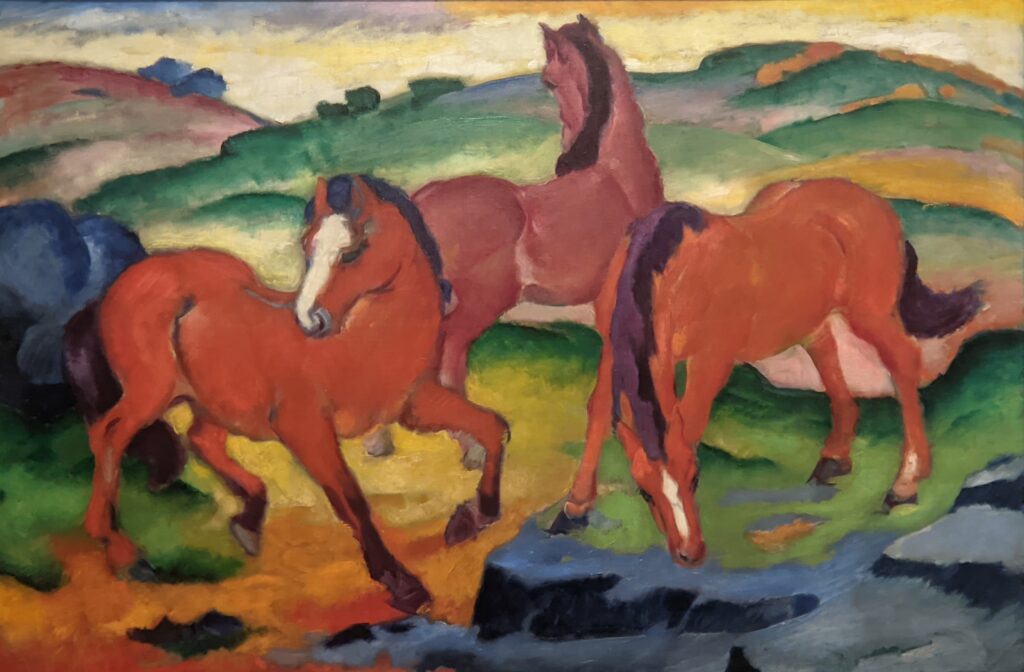

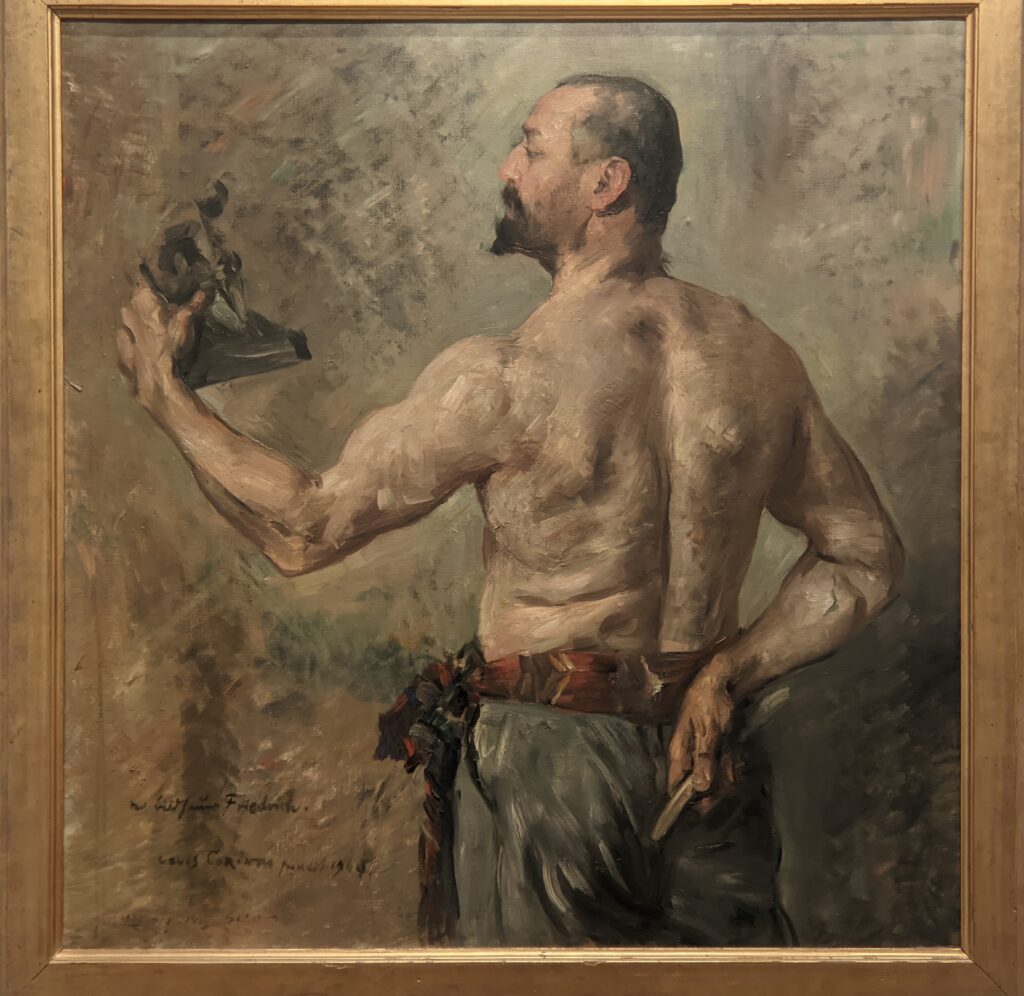

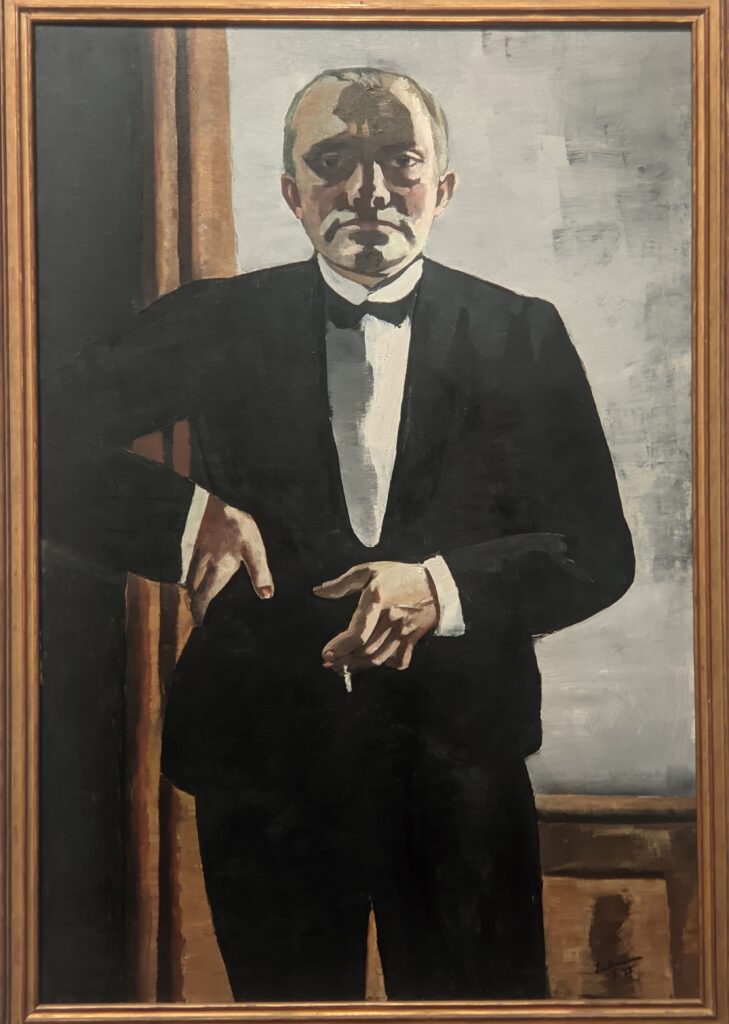

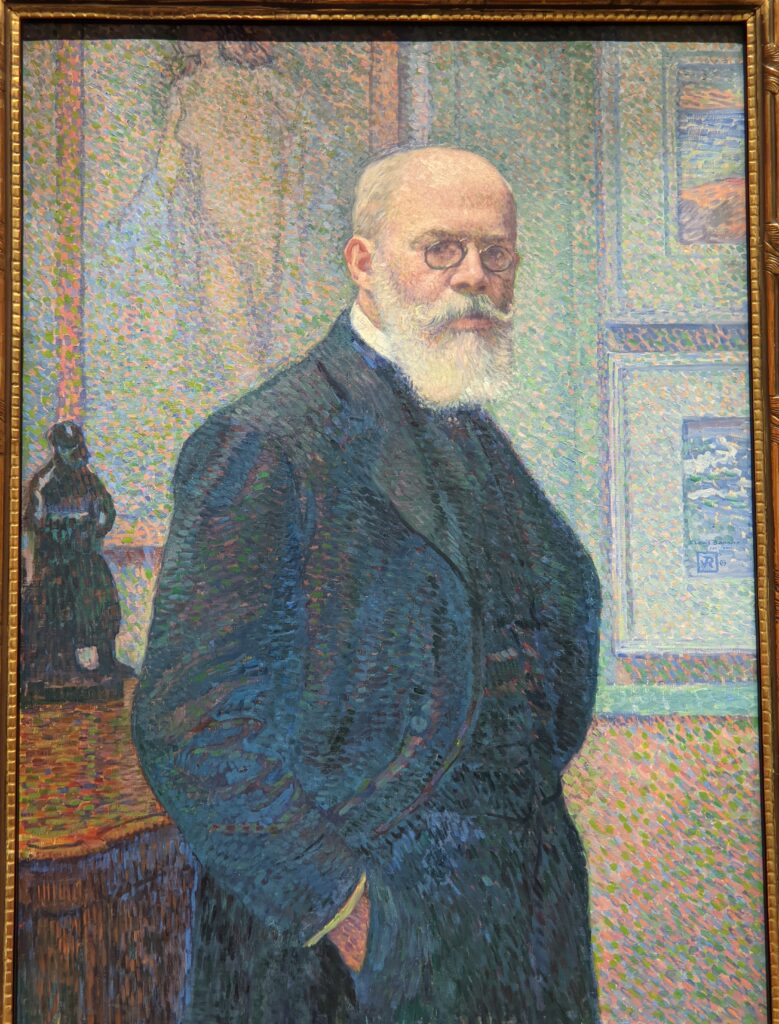

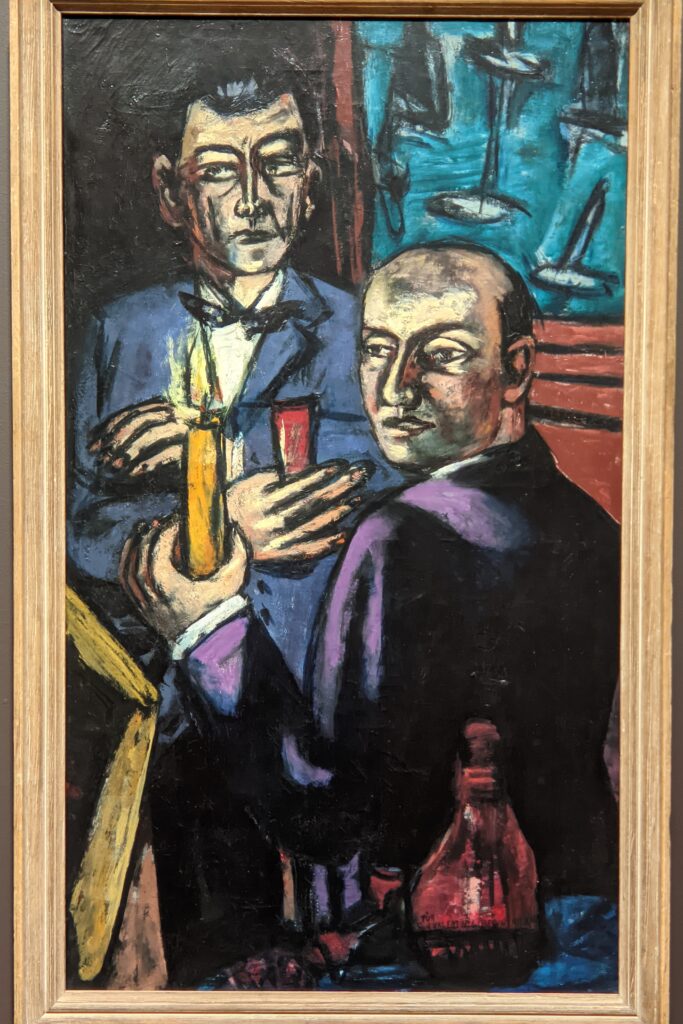

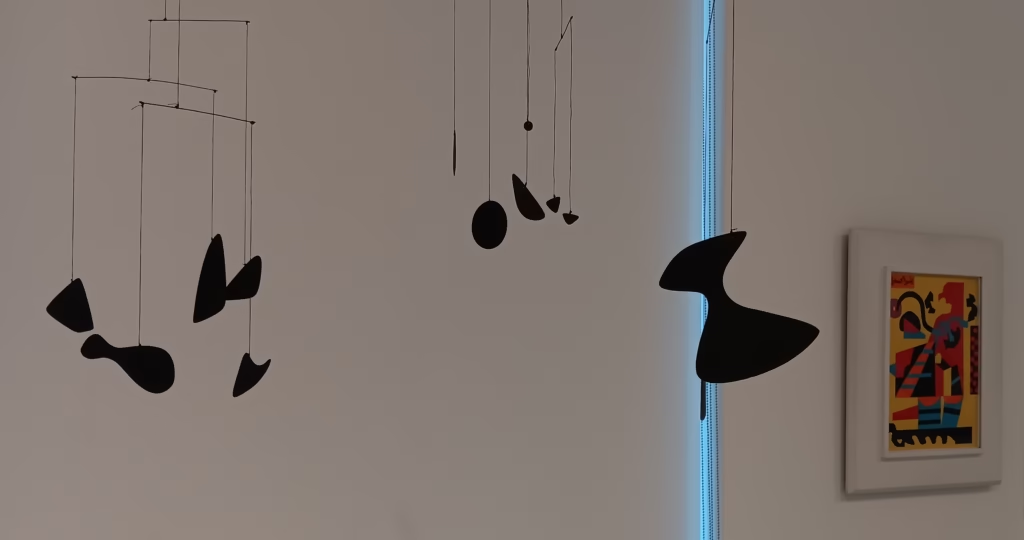

The Fogg Art Museum, opened in 1896, is the oldest component of the Harvard Art Museums (part of Harvard University) which includes two additional museums and four research centers. The three museums were integrated into a single institution in the 1980s — with an amazingly strong collection of Italian Renaissance, Pre-Raphaelite, 19th-century French and 20th-century Austrian/German Expressionist paintings — and, fortunately, united in the renovated building at 32 Quincy Street (opened in 2014) to allow greater access to the 250,000-piece collection, which also includes Chinese jades and bronzes, and works of art in all media from the ancient Mediterranean world.

BELOW LEFT: Artur Niezgoda and Channing Page

Dedication

We wish to thank Channing Page for her assistance and all-important advice with regard to our selection of venues for art lovers in Cambridge and Boston. In addition to being a true friend and source of inspiration, Channing possesses a thirst for knowledge combined with an appreciation for all of the arts as an amelioration of the human condition, a source of healing and joy. Channing cherishes her family and friends, and is a devoted daughter.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Founded in the capital of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1870, the Museum of Fine Arts (abbreviated as the “MFA Boston”) is the 20th-largest art museum in the world (measured by public gallery area). More than 8,000 paintings are on display in the MFA Boston, which possesses one of the most encyclopedic collections in the United States consisting of 450,000 works of art.

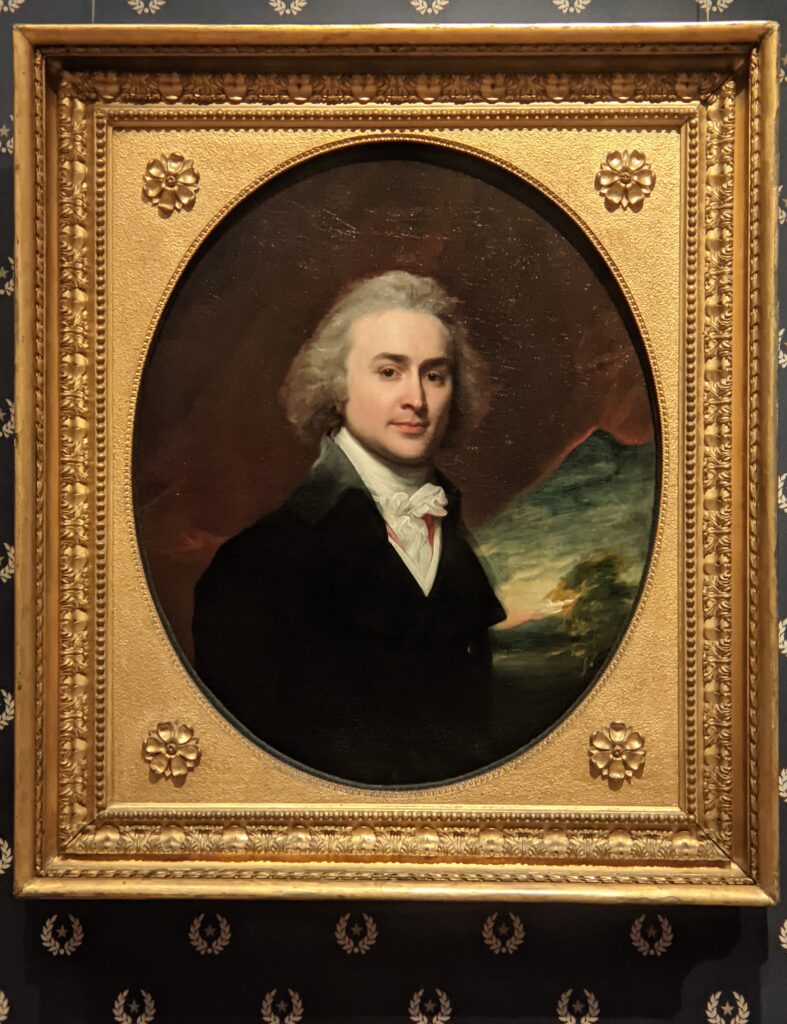

The “Portrait of Roswell Gleason” 1848 (above) by Edward Dalton Marchant is displayed in the museum’s rooms from the Roswell Gleason House — built circa 1840 in Dorchester, Massachusetts. The formal Dining Room (in the background) and a sitting room were purchased by the MFA Boston in 1976 from a descendant of Gleason, a prosperous pewter manufacturer. The acquisition of these two rooms represents a most auspicious use of the museum’s Period Room Restoration Fund — the Roswell Gleason House burned in 1982.

Previous Exhibitions at the MFA Boston

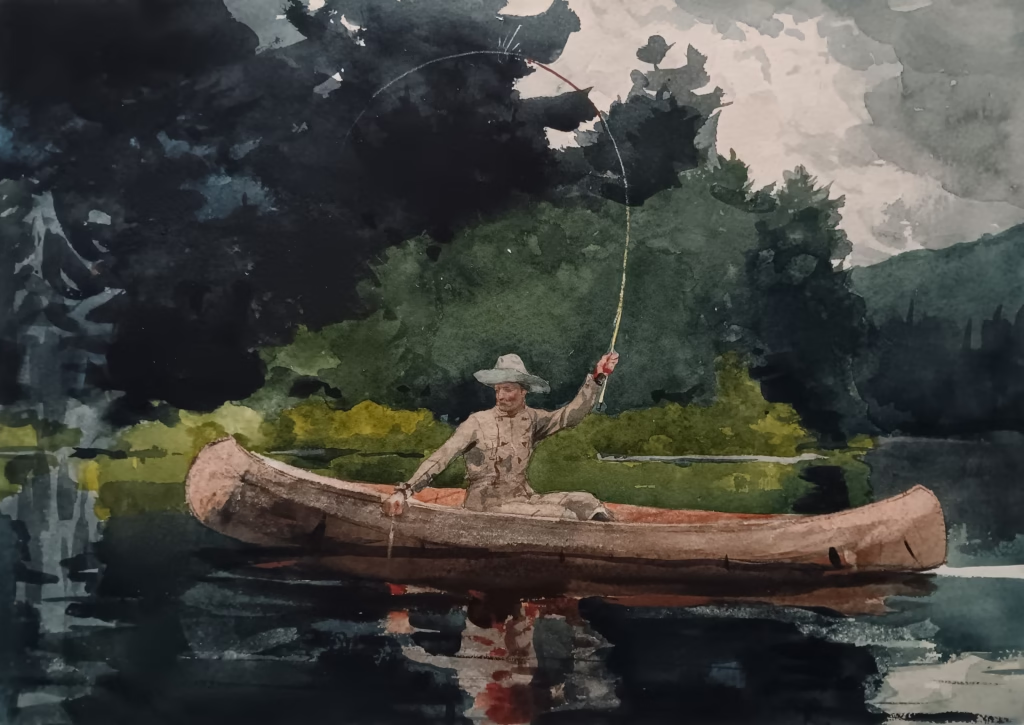

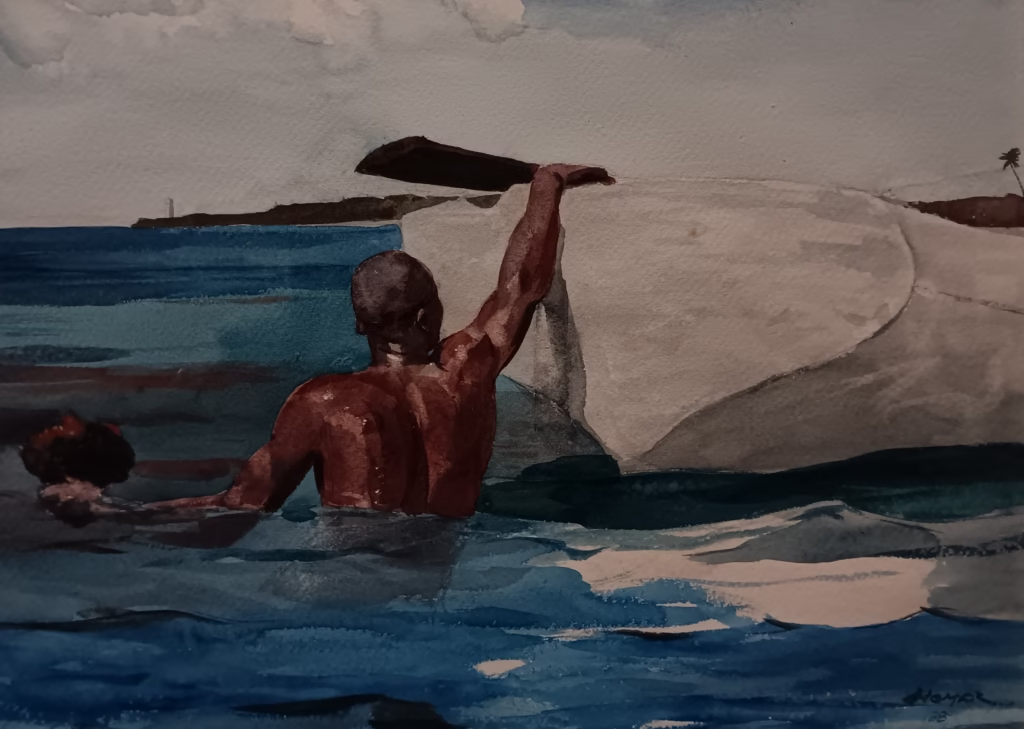

The MFA Boston houses the world’s largest collection of Winslow Homer’s watercolors (almost 50), plus 11 oil paintings. Due to the works’ sensitivity to light, these amazing and fragile watercolors on paper have not been displayed together in nearly half a century.

Born in Boston, Winslow Homer (1836–1910) had a close relationship with New England and with the MFA Boston, which acquired its first painting by the artist, Fog Warning (above), in 1894. The first watercolor, Leaping Trout (below), came into the collection soon after, and over the 20th century the Museum amassed a large collection of Homer’s work across a variety of media.

With his versatile and experimental approach to painting, Winslow Homer transformed the medium of watercolor, and this exhibit would have been stronger if the Museum’s curators had excluded his oil paintings and drawings, and focused exclusively on watercolors created by Homer and other artists. Nevertheless, Homer’s luminous perspectives transport viewers from the rugged Maine coast to rocky Gloucester in Massachusetts, through the Adirondack Mountains to sun-drenched Caribbean waters, and then beyond to seaside England.

The Winslow Homer Exhibit Closed in January 2026

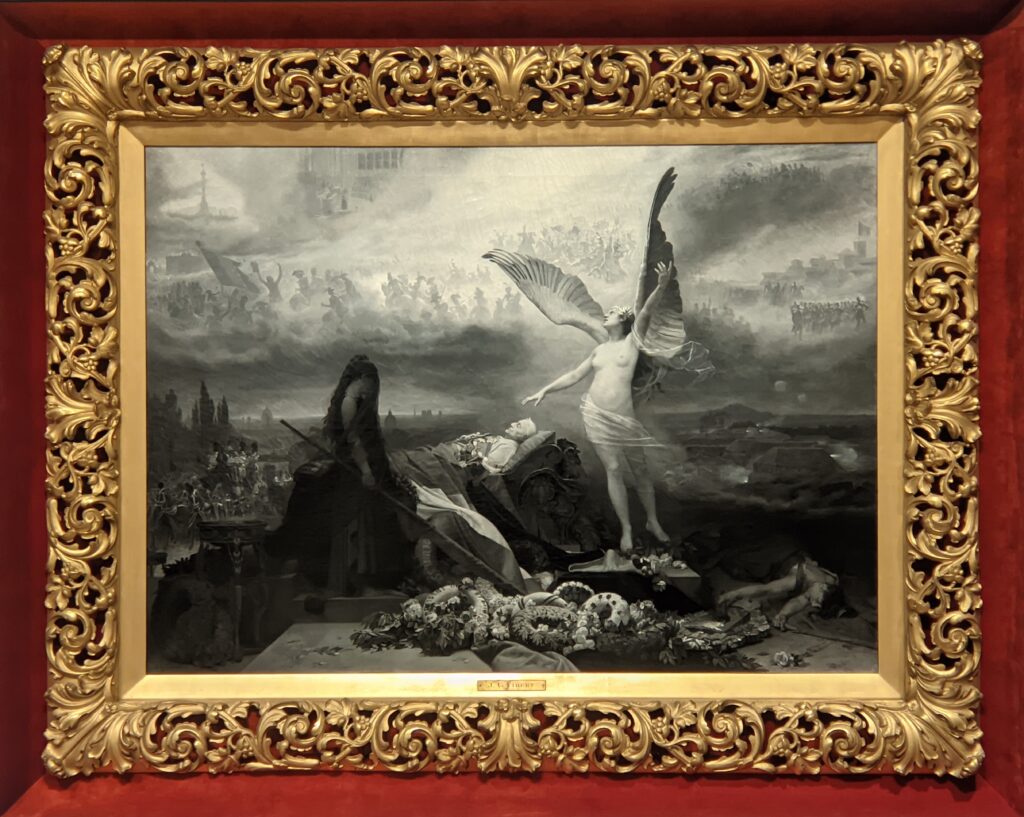

RACHEL RUYSCH

The still life paintings of Dutch artist Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750) are primarily floral bouquets, rich and alive with movement. Her petals and stems droop and rise, as lizards crawl across her colorful canvases (replete with birds’ nests and luscious fruit) to capture butterflies. These astonishing displays, rendered with a skill that eclipsed many of her male contemporaries, earned Ruysch fame across Europe in her lifetime — an era when few women attained her level of artistic prominence. This exhibit closed in December 2025.

The Roulin Family Portraits

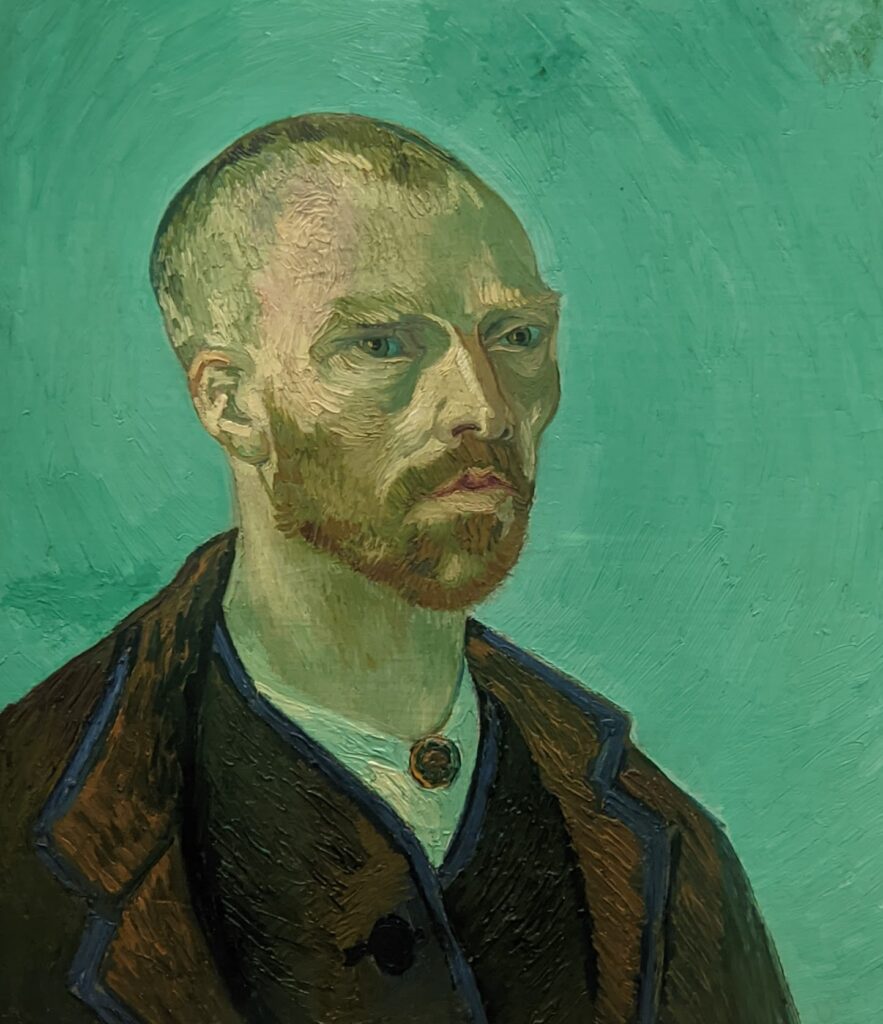

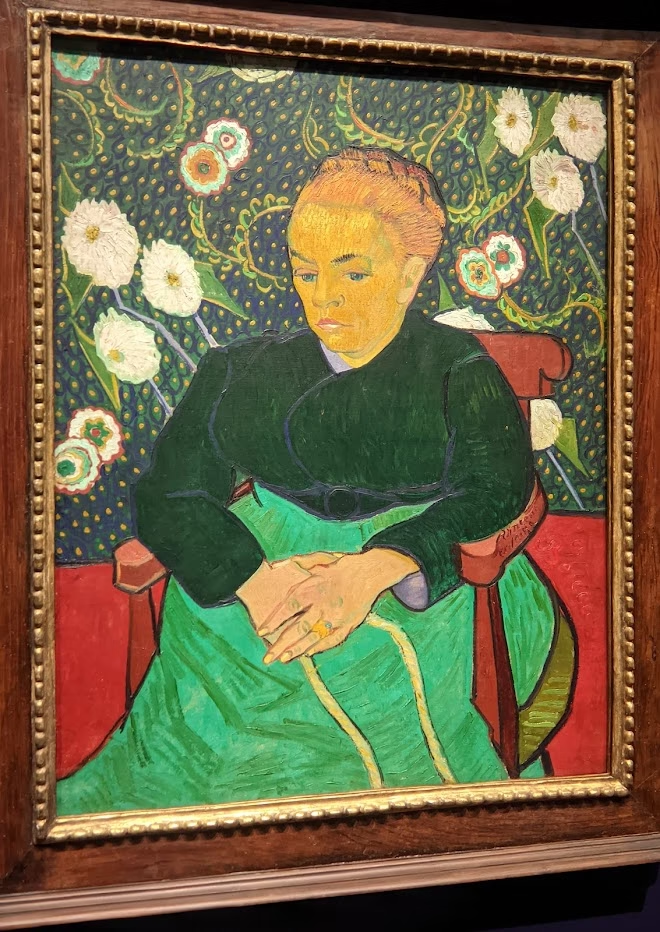

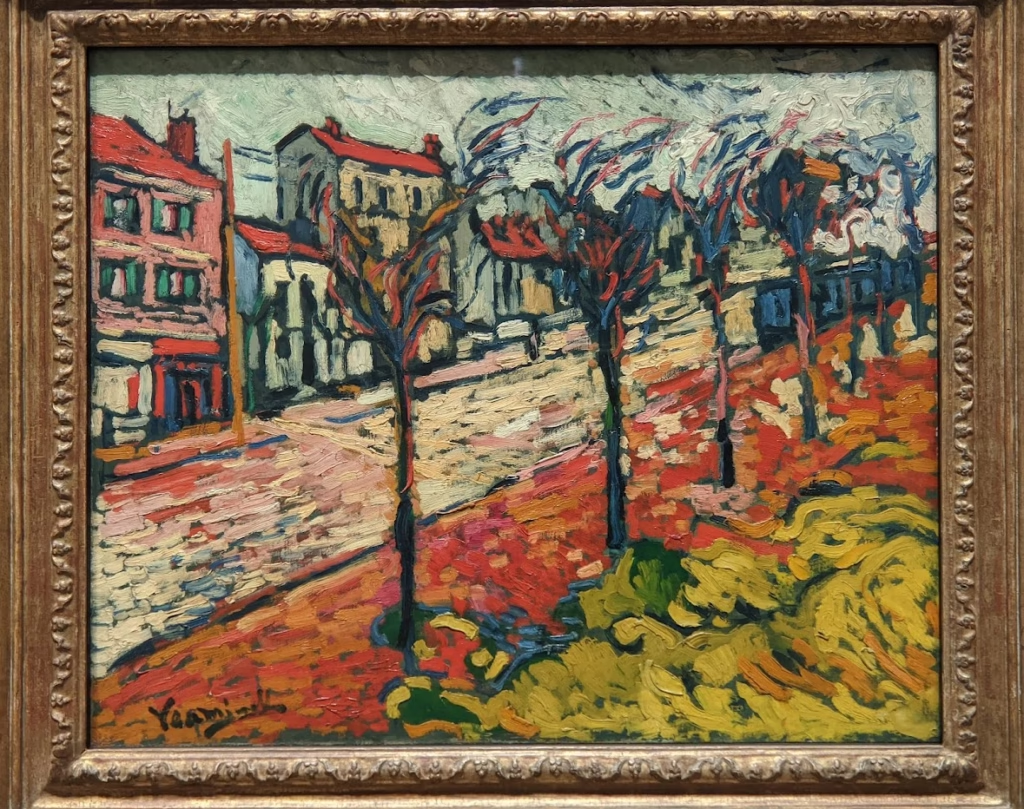

Throughout the summer months of 2025, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston presented “Van Gogh: The Roulin Family Portraits,” a collaboration with the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

March — September 2025

During the artist’s stay in Arles (1888-89), in the South of France, Van Gogh created a number of portraits of the family of his friend, the postman Joseph Roulin, including the Postman’s wife, Augustine, and their three children, Armand, Camille, and Marcelle.

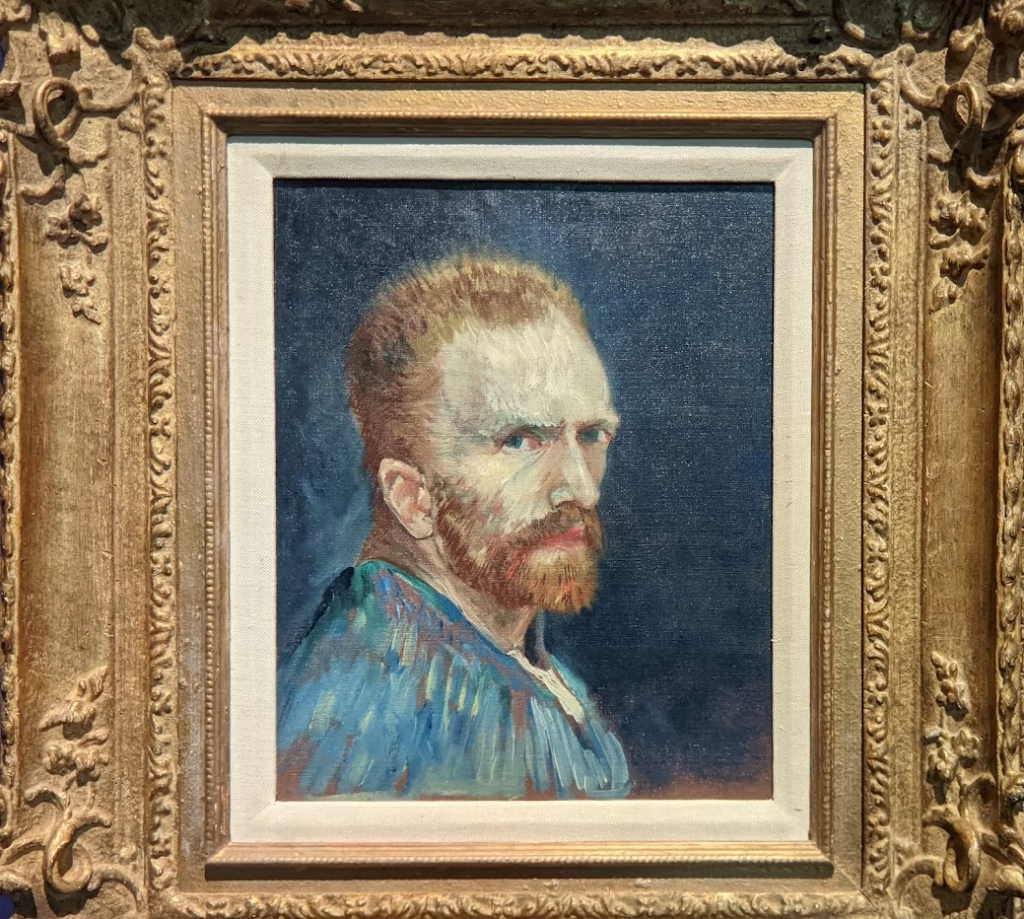

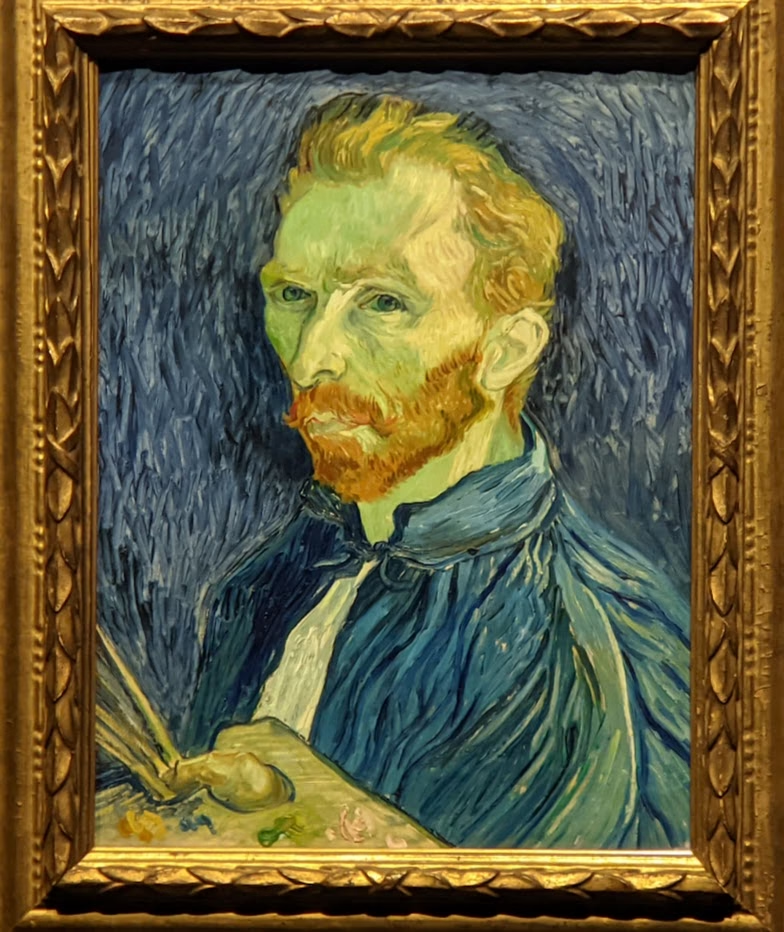

Van Gogh (1853 — 1890) once wrote, “What I’m most passionate about … is the portrait, the modern portrait.”

While Vincent’s tender relationship with the postman and his family formed the centerpiece of this exhibition, which featured 23 works of art by Van Gogh, the show also included Japanese woodblock prints, Netherlandish art which influenced the artist’s approach to portraiture, and paintings by Gauguin and Bernard that were familiar to Vincent.

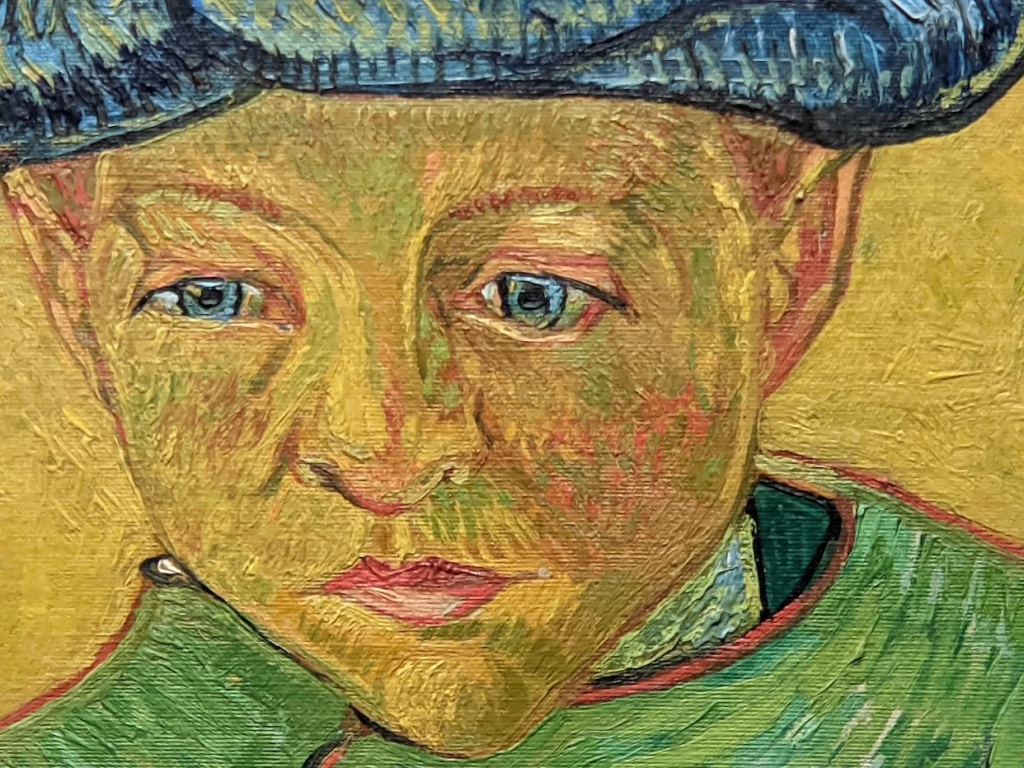

In 1888, 11-year-old Camille Roulin sat for his first portrait (above right) which Van Gogh gave to the Roulin family as a gift. Afterward, the artist made a copy (below) using the same composition, size and shape. The warm glow of the yellow background indicates that it was originally painted by gaslight in Vincent’s studio. In the case of portraiture, Van Gogh was able to create copies without the need for the sitter to pose a second time. Repetitions allowed the artist to make changes, stylistic variations, and adjustments to the composition, and this practice also increased his visibility. Van Gogh kept the second version in Arles for six months, and then sent it to his brother Theo in Paris, where it was seen by potential buyers, critics, and Vincent’s fellow artists.

“The Roulin Family Portraits” Closed in September 2025

The MFA, Boston’s presentation of its collection leads one through a fine visual journey of understanding, beginning with fine examples of French naturalist painting by Breton and Dagnan-Bouveret (pictured above), and continuing with Frits Thaulow, the Norwegian painter who combined the careful and detailed brushwork of Realism with Impressionism, especially in his treatment of the movement and flow of water (below).

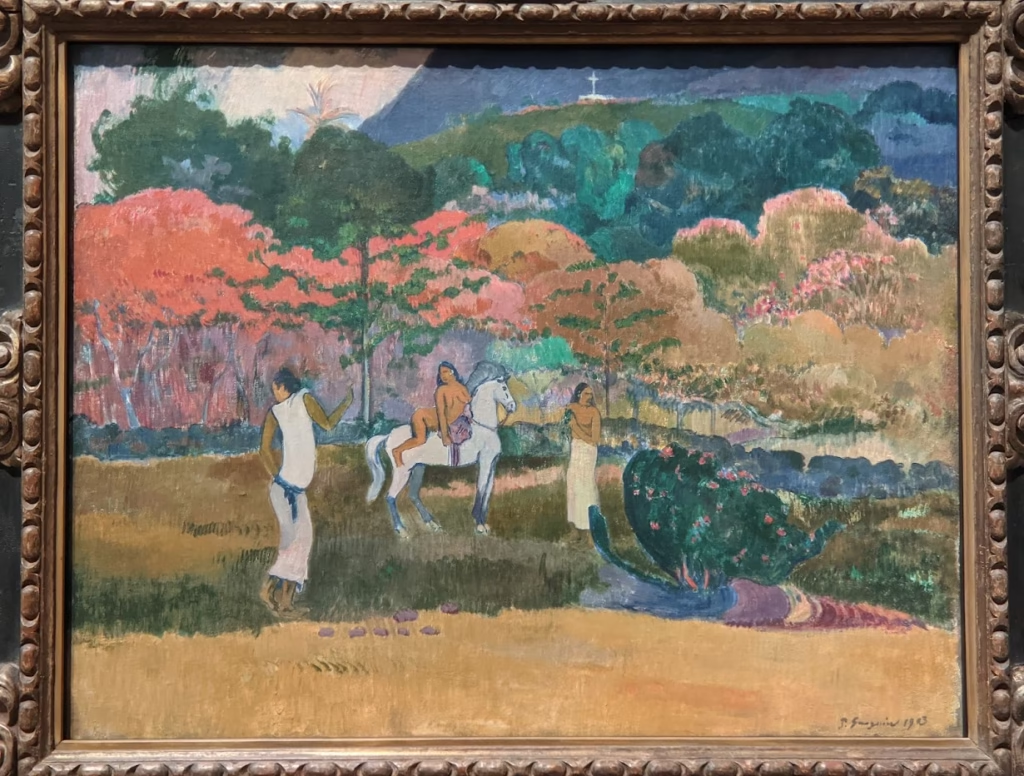

The expressive use of color by Van Gogh and Gauguin would profoundly influence the Nabis and Fauvist painters — including Vuillard, Bonnard, Matisse and Vlaminck — and the German Expressionists. After seeing Van Gogh paintings for the first time, Maurice de Vlaminck stated, “I loved” Vincent “more than my own father.”

The Special Exhibit “Georgia O’Keeffe & Henry Moore” Closed at the MFA, Boston in January 2025

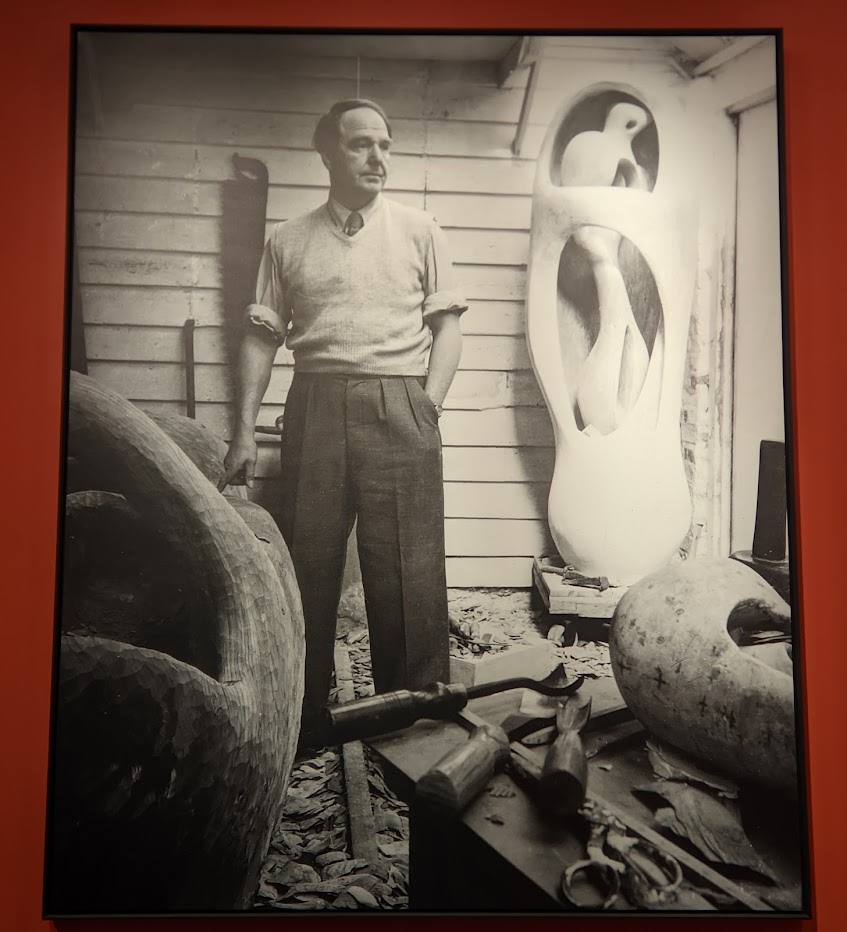

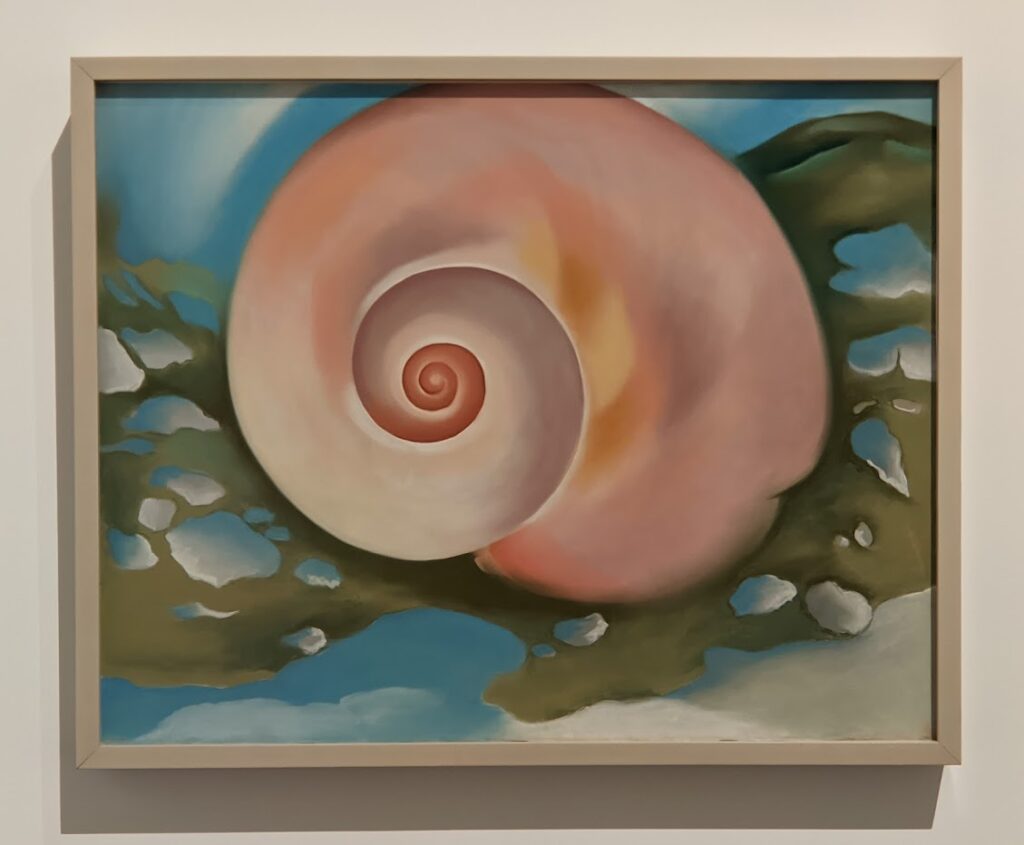

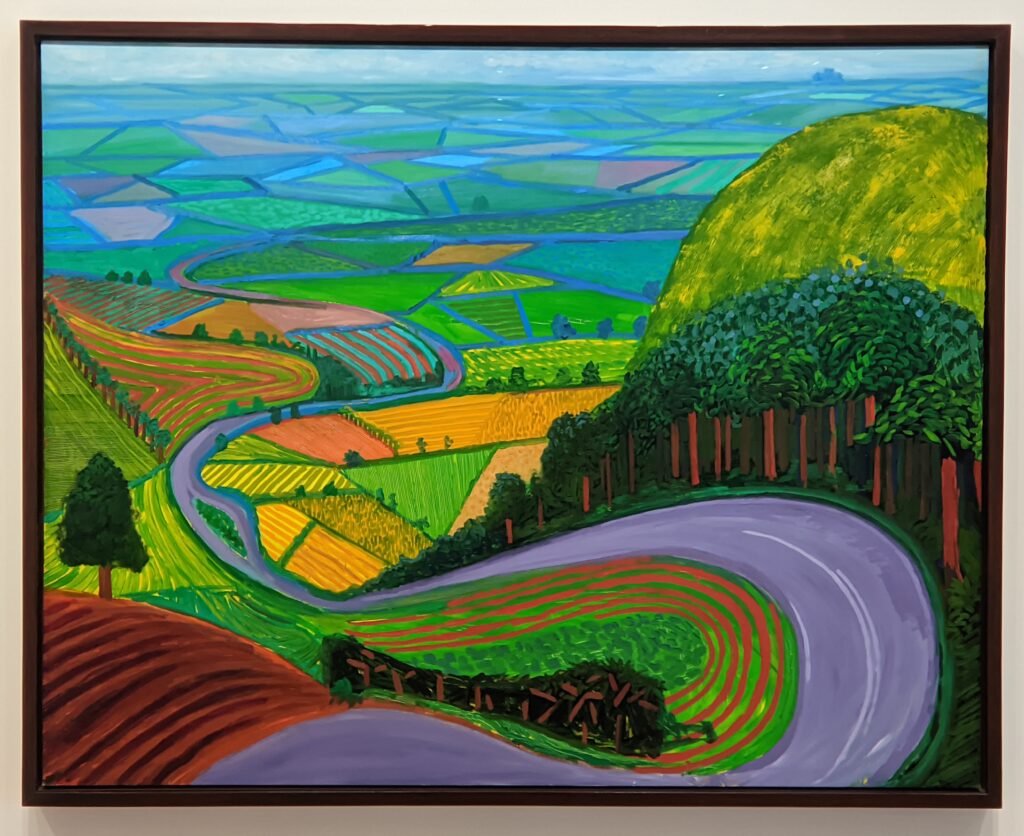

Famous for their distillations of natural forms into abstraction, American painter Georgia O’Keeffe (1887 — 1986) and British sculptor Henry Moore (1898 — 1986) were inspired by long walks and careful observation in the distinctive landscapes of their native countries. O’Keeffe and Moore turned nature into art.

“Tender Loving Care”(below) Was on View Through January 12, 2025

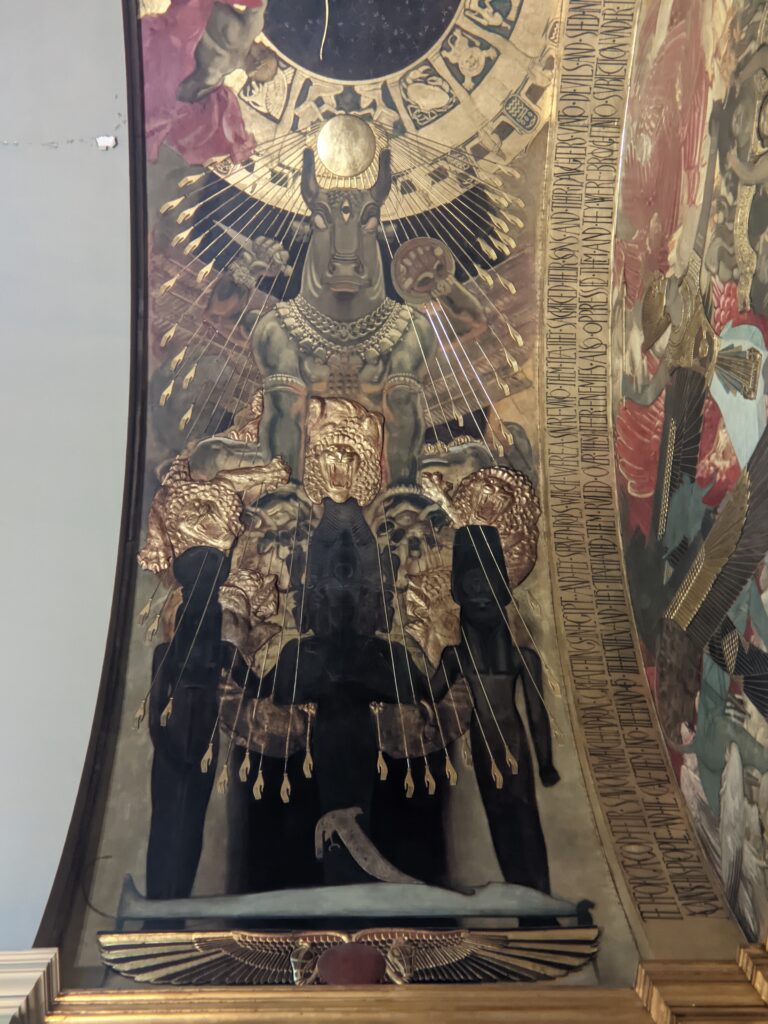

“Dalí: Disruption & Devotion” Closed on December 1, 2024

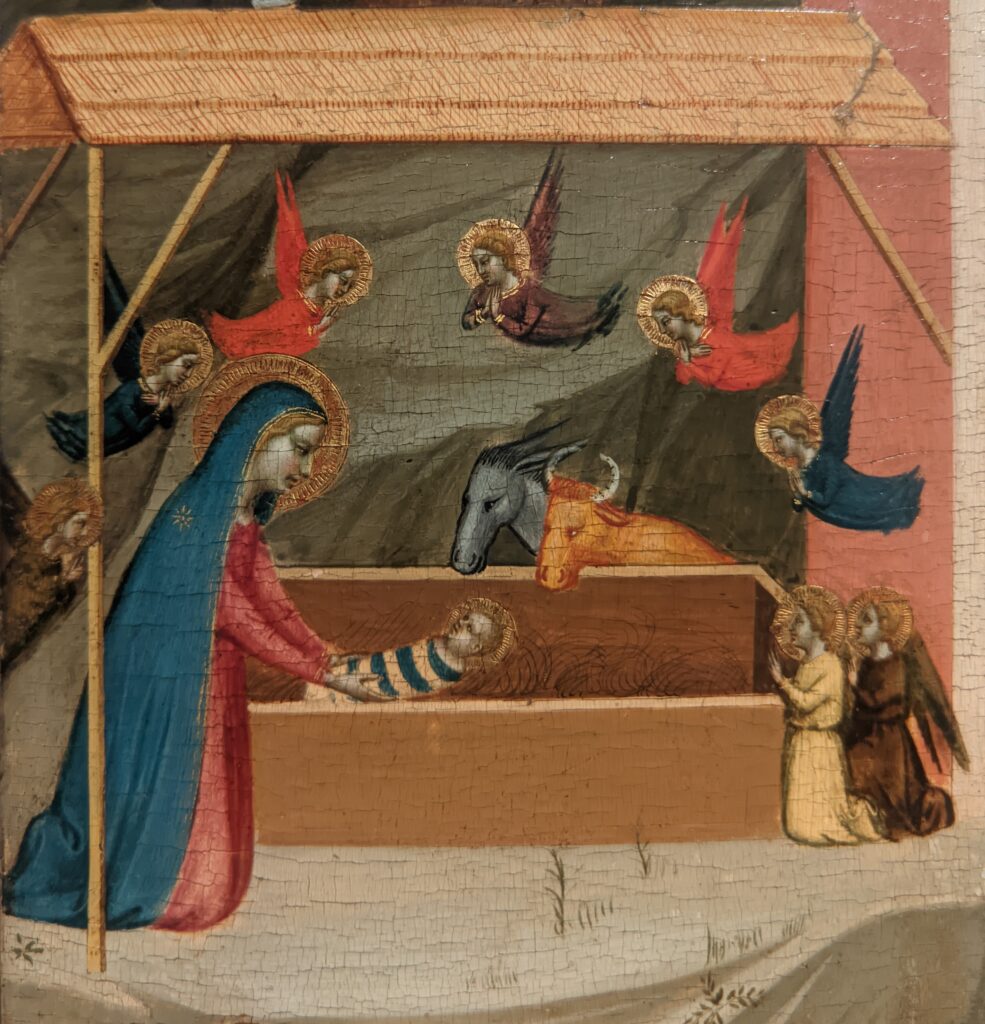

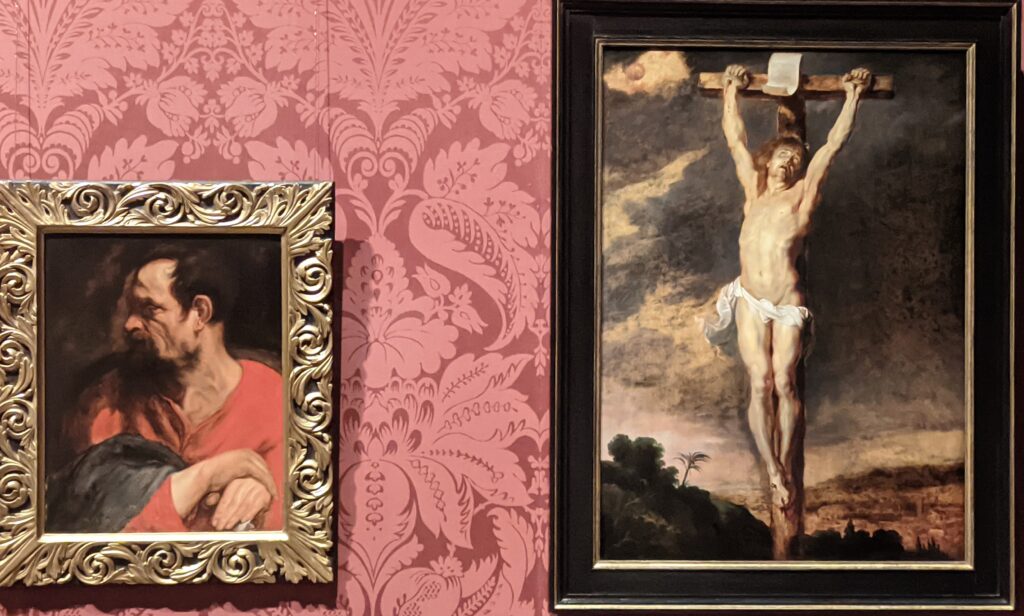

Visitors to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 2024 may have been surprised to learn that Salvador Dalí was an artist deeply committed to the past. The Museum’s first-ever exhibition of work by Dalí revealed his devotion to European art and artists from the 15th through 18th centuries. This exhibition explored Dalí’s religious embrace of Catholicism in the 1950s, which led him to focus on sacred imagery.

Dalí saw himself as a master of the modern age, an admirer of his predecessors who had defined their eras — artists such as Albrecht Dürer, El Greco, Diego Velázquez, Francisco Goya, and others whose works are also represented in this exhibit.

Dalí’s other classical influences included Raphael, Bronzino, Zurbarán and Vermeer. Dalí mined the past, yet expressed himself through the ideas of the 20th century, from the irrational creations of the subconscious inspired by the theories of Sigmund Freud to the discoveries of nuclear physics. Dalí disrupted the old to make it new again.

Gala, Dalí’s wife and muse, modeled in many guises for the artist. She represented Saint Helena (above), the mother of 3rd-century Roman emperor Constantine the Great. The cross, an emblem of Saint Helena, is held in one hand while her other holds the Gospels. Special loans from the Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida and works on paper from a private collection are shown alongside this Boston Museum’s European paintings made by the artists whose works most inspired Dalí.

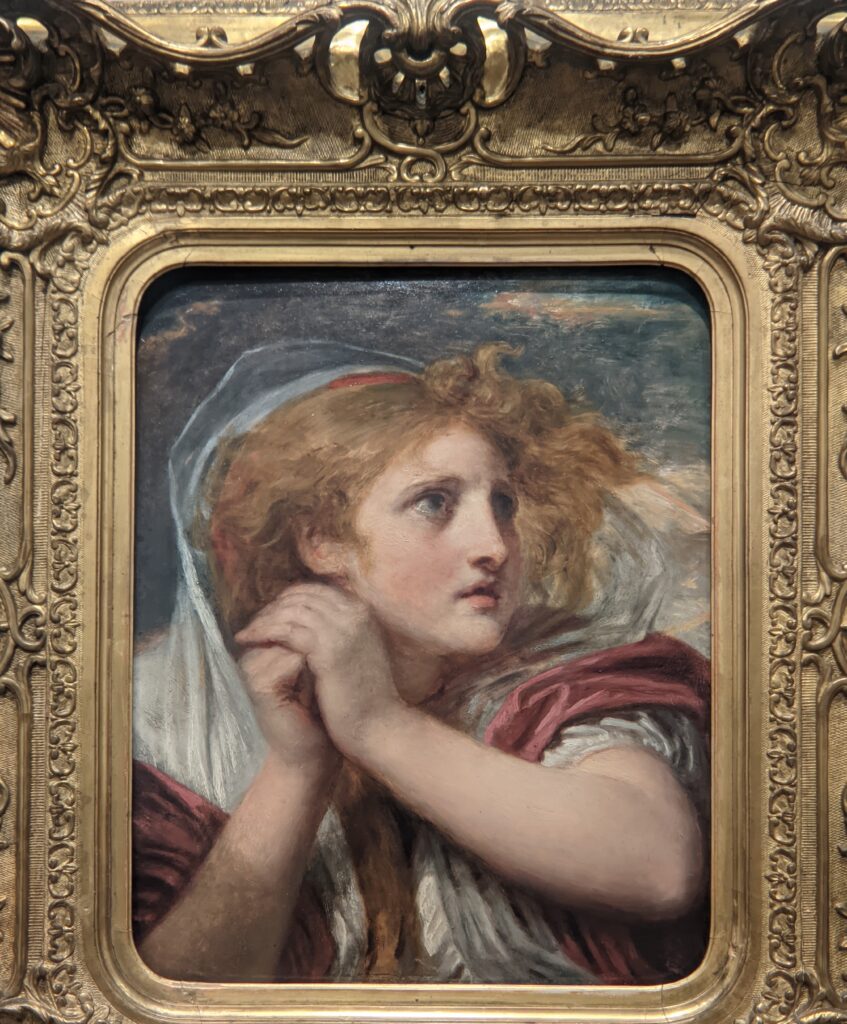

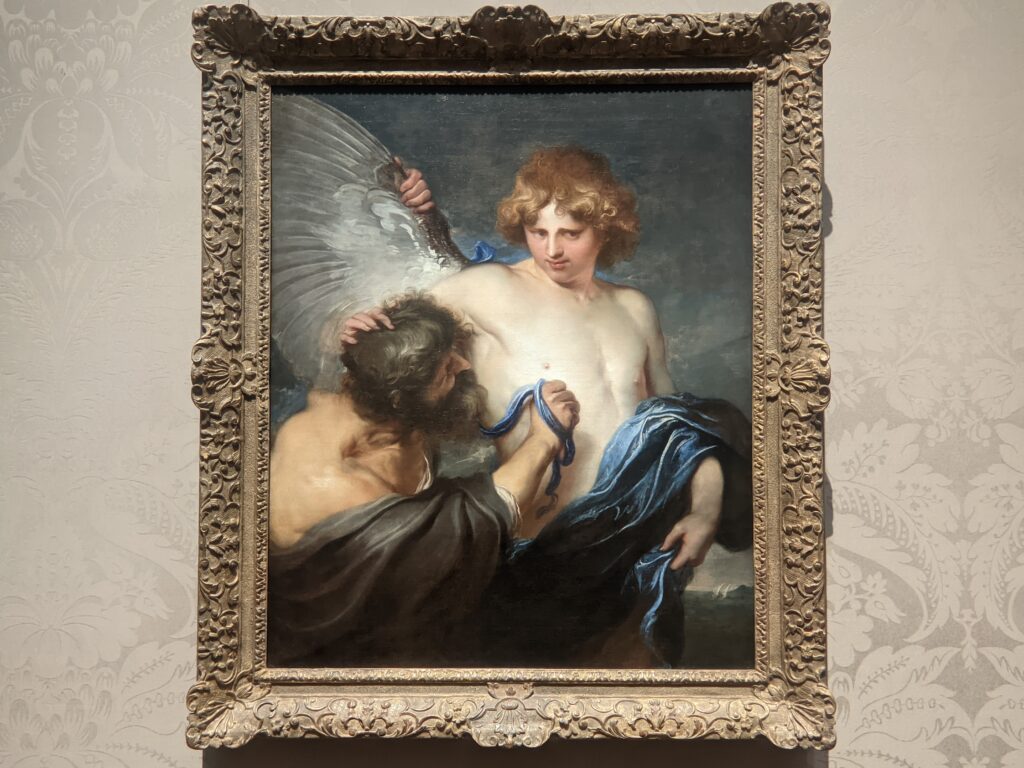

In European art across the centuries, angels and light serve as messengers between the spiritual and human realms. In Goya’s “Annunciation” the beam of light indicates the moment Mary learns from the angel Gabriel that she is carrying the son of God. This study for a large altarpiece in a monastic chapel in Madrid gives us a glimpse into Goya’s creative process, his fluid brushstrokes demonstrating the technique he used for a preliminary design.

Like the heavenly illumination in Goya’s “Annunciation” (above), shafts of light pierce through the silvery tones of the coastal view (below left) in “The Angel of Port Lligat,” bestowing a mystical feeling. This isolated coastline appears frequently in Dalí’s oeuvre.

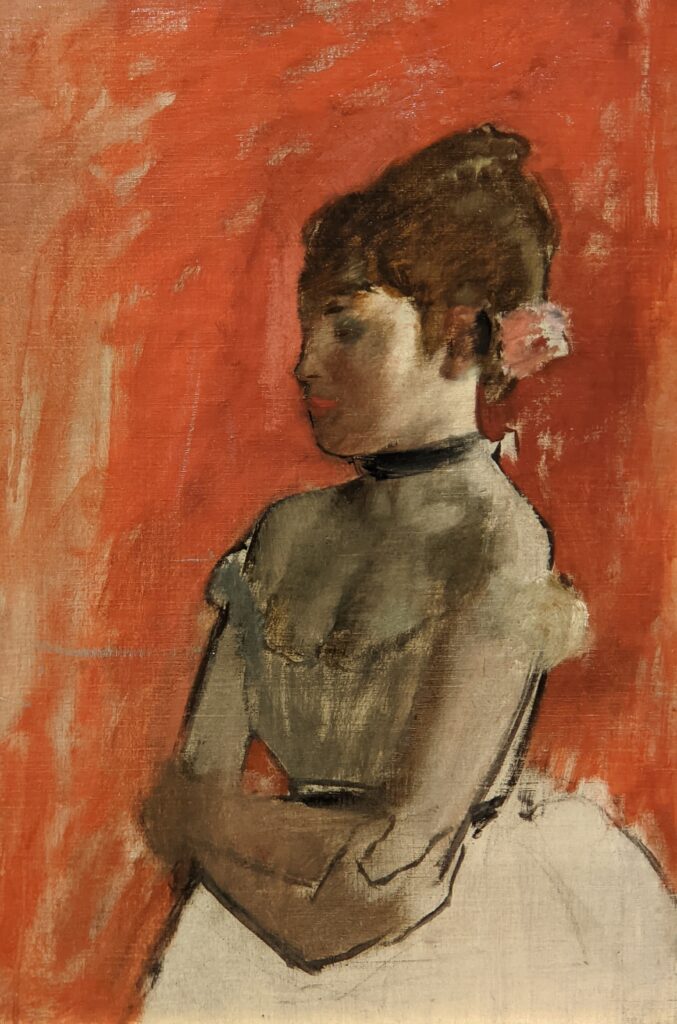

Dalí is one of many artists to admire El Greco. The Impressionist Edgar Degas owned this very painting of Saint Dominic (above). Dalí’s representation of saints and angels often share a sense of spiritual isolation in the similarly subdued grays, blues and browns as El Greco’s pious saint.

El Greco’s distinctive elongated forms, distilled composition, and restrained palette convey that spiritual intensity so admired by Dalí.

Dalí particularly revered El Greco for his visions of holiness, and he once wrote that El Greco’s “brilliant paintings” offer “a feeling and spirituality so great that it transfers our imagination beyond that which surrounds us ….” In El Greco’s painting, Saint Dominic — founder of the Dominican order — kneels in solemn devotion before a crucifix, just as Gala is seen kneeling in many of Dalí’s works of art.

As Dalí focused on religious themes, he often posed Gala in the role of the Madonna or other saints.

Dalí was born in Figueres (Catalunya, Spain) in 1904; he lived in France during the Spanish Civil War (1936 — 39), then he and he his wife Gala moved to the United States for eight years before returning to Port Lligat in Catalonia in 1948. Spending the wartime years in the United States enabled Dalí to establish his international reputation, fame. He exhibited his art in New York and elsewhere, raised his profile through frequent interviews and public appearances, and crafted his celebrity through provocative statements and theatrical behavior, including appearances with his pet anteater.

He returned to Europe at the height of his career, one of the most recognizable people in the world. Despite his fame, however, Dalí continued to acknowledge the artists of past centuries who had inspired him since his first days as a student.

A bountiful spread of cheeses, vegetables, meats and breads reflected both the ingredients of a hearty meal and abundance for 17th- and 18th-century audiences. In “Eggs on the Plate Without the Plate” (below left) Dalí opposes this typically European vision of plenty with a meager display: exquisitely painted fried eggs against a barren landscape. He presents a typical still life subject (food) quite differently from the customary enticing arrangement. One egg hangs from a string, two are on a plate, and a pocket watch dangles at left. Window panes, unseen in the composition, are reflected in the yolks. Dalí claimed to have been inspired by his “intra-uterine” memories (recollections from inside his mother’s womb), in which his most “splendid vision” was that of “a pair of eggs fried in a pan without a pan.”

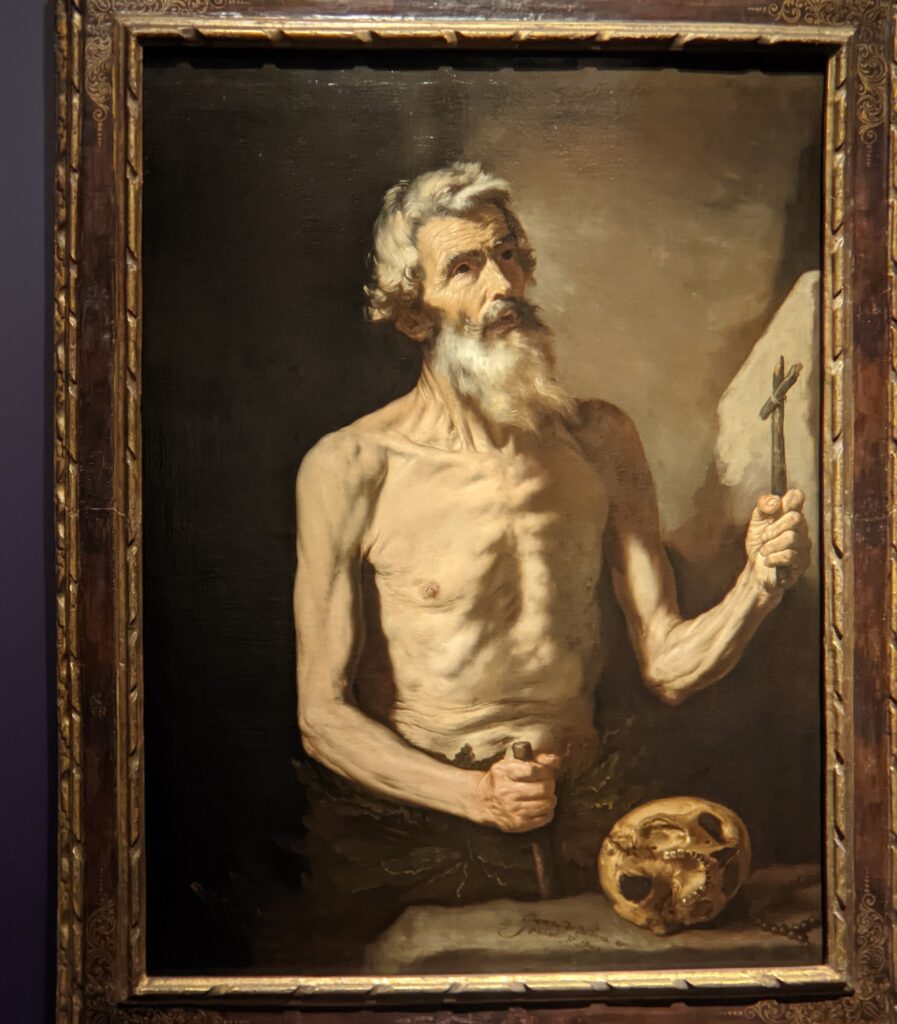

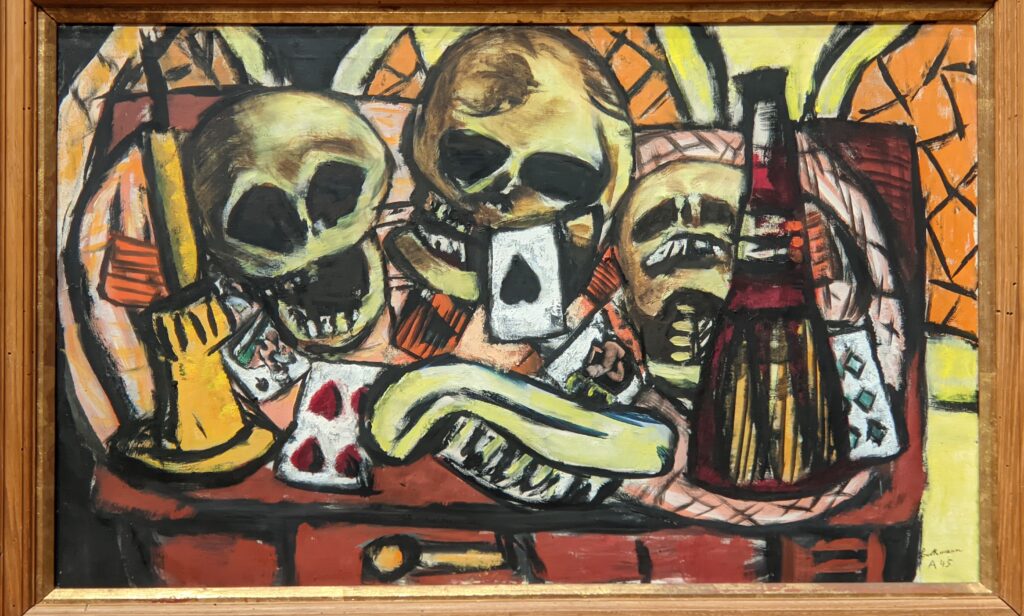

For centuries, artists have used skulls as symbolic reminders of human mortality, often referred to as memento mori (Latin for “remember that you have to die”). José de Ribera utilized the skull to make an explicit connection between aging, death, and the necessity of religious faith in his depiction of Saint Onophrius (above right). Ribera painted with great realism the hermit’s dirty fingernails, hollowed cheeks, and flesh sagging from his emaciated frame.

Dalí repurposed the skull motif frequently in his work in the 1930s and beyond. In nearly photographic renderings, he aimed to “materialize the images of concrete irrationality with the most imperialist fury of precision.” Dalí’s skulls defy logic and reality, becoming animate, malleable objects often with sexualized overtones.

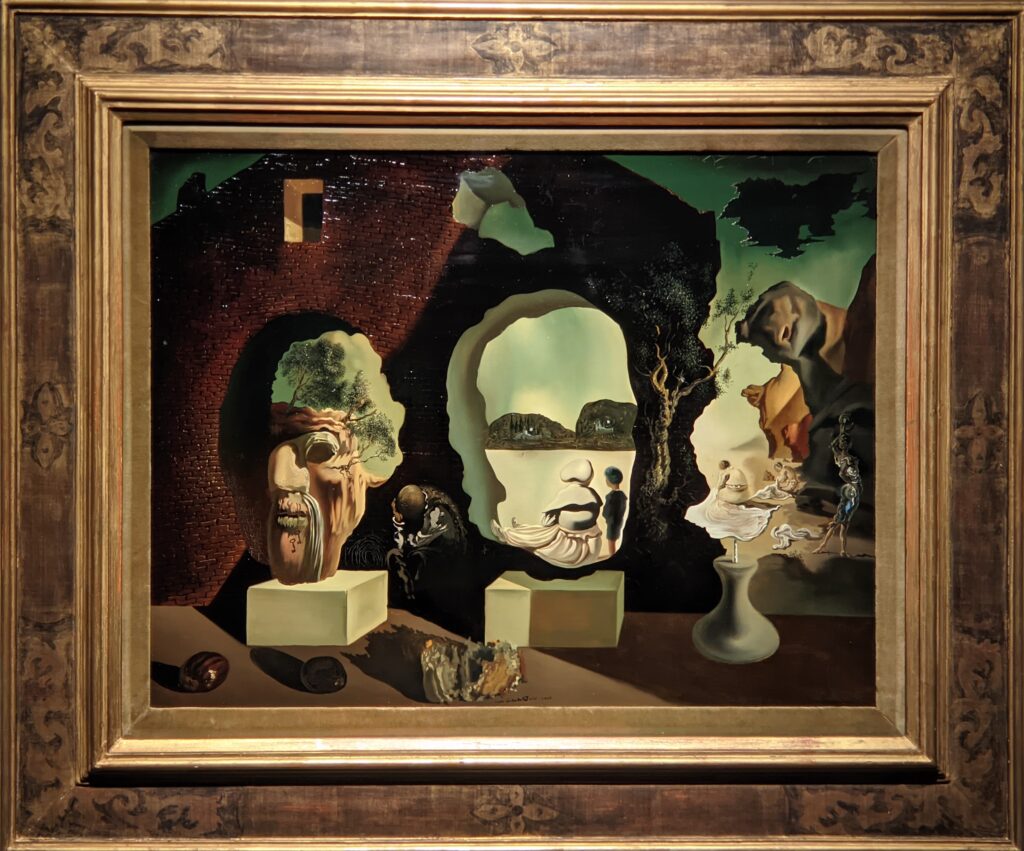

What do you see in the center of this picture — two women in 17th-century dress with wide collars, or an older man’s face? This “double-image” (which Dalí called a paranoiac-critical image) presents two different compositional ideas co-existing within a single painting. Based on a famous bust of the 18th-century French Enlightenment philosopher Voltaire by the sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon, the distinctive face emerges as an optical illusion within the forms of many figures at center.

Surrealists were deeply at odds with Voltaire’s belief in reason and rationalism. As Dalí wrote, “Voltaire possessed a peculiar kind of thought that was the most refined, most rational, most sterile, and misguided not only in France but in the entire world.” The title Slave Market refers to this divide, as Dalí and the Surrealists considered Voltaire’s philosophy to be ideological slavery.

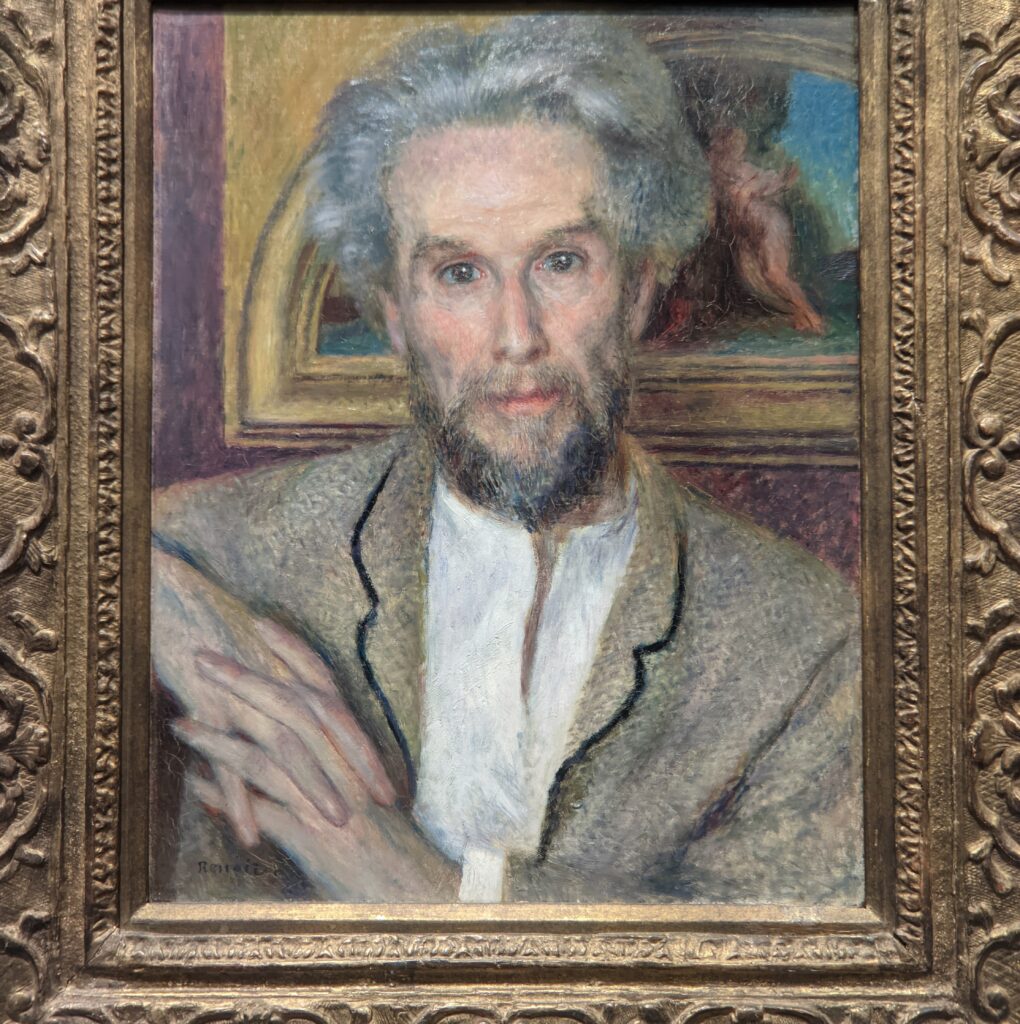

At the age of 16, in 1921, Dalí’s mother died from cancer. His mother’s death, he said later, “was the greatest blow I had experienced in my life. I worshiped her.” In 1922, Dalí moved to Madrid to study art and where he began what would become a lifelong relationship with the Prado Museum, which he believed was “incontestably the best museum of old paintings in the world.” Dalí had a sister, Ana María, three years his younger, whom he painted 12 times between 1923 and 1926. Ana María served as the model for “Girl’s Back” (above right), which is beautifully displayed in Boston between canvases by Salomon de Bray (above left) and Diego Velázquez. De Bray’s attention to the textures of fur, fabric, and delicate curls of hair reveals a remarkably lifelike quality that would have appealed to Dalí, given his realist tendencies. Known as tronies, works like this one by De Bray are head studies after live models rather than commissioned portraits.

Dalí was actively thinking about Dutch painting at the time he painted “Girl’s Back” — in fact, he wrote to his friend Federico García Lorca in 1926: “I dream of going to Brussels to copy Dutch painting in the museum. You have no idea how much of myself I have put into my painting, how much affection I feel as I paint my windows open to the rocky sea, my baskets of bread, my girls sewing, my fish, my skies resembling sculptures.” Dalí held his first solo exhibition in Barcelona in November 1925, five months before he made his initial trip to Paris, where he met Pablo Picasso (whom he revered) and gained his earliest introduction to many Surrealists through his fellow Catalan Joan Miró.

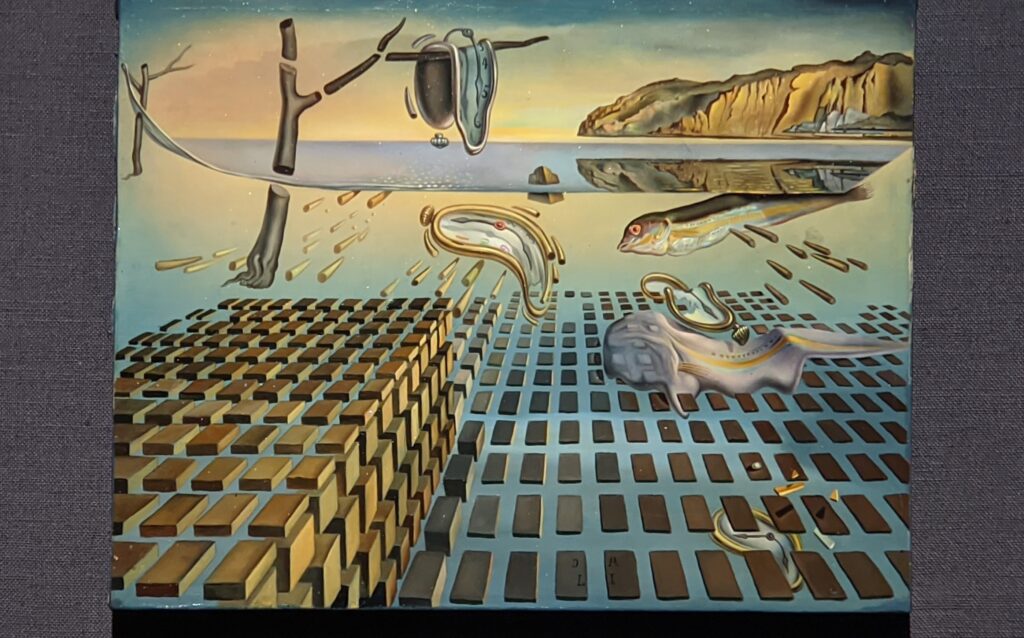

“The First Days of Spring” (above) is one of Dalí’s earliest Surrealist paintings. The receding view and long shadows make us perceive these images as tangible forms in space, while our logical brain knows that there is no basis in reality for such dream-like figures. Dalí employed vanishing point perspective, a technique developed by Renaissance painters that uses receding parallel lines to create the illusion of depth, at a time when many of his contemporaries preferred flat, abstract compositions.

“Dalí — Disruption and Devotion”

Velázquez’s portrait of Góngora (above right) is among his most incisive psychological studies and a key early work. His subject, Luis de Góngora, a poet known for his unique style, had become embittered during his years at the Spanish court. Velázquez shapes Góngora’s formidable head, with his down-turned mouth and guarded gaze, with smoothly blended brushstrokes that define the topography of his features. Painted during Velázquez’s first trip to court, it may have led to his appointment as an official painter to the king. In his early 20s, Dalí grew a neatly trimmed mustache. In later decades, he cultivated a more flamboyant mustache in the 17th-century manner of the master painter Diego Velázquez, and it was perhaps this look that became the most well known Dalí icon.

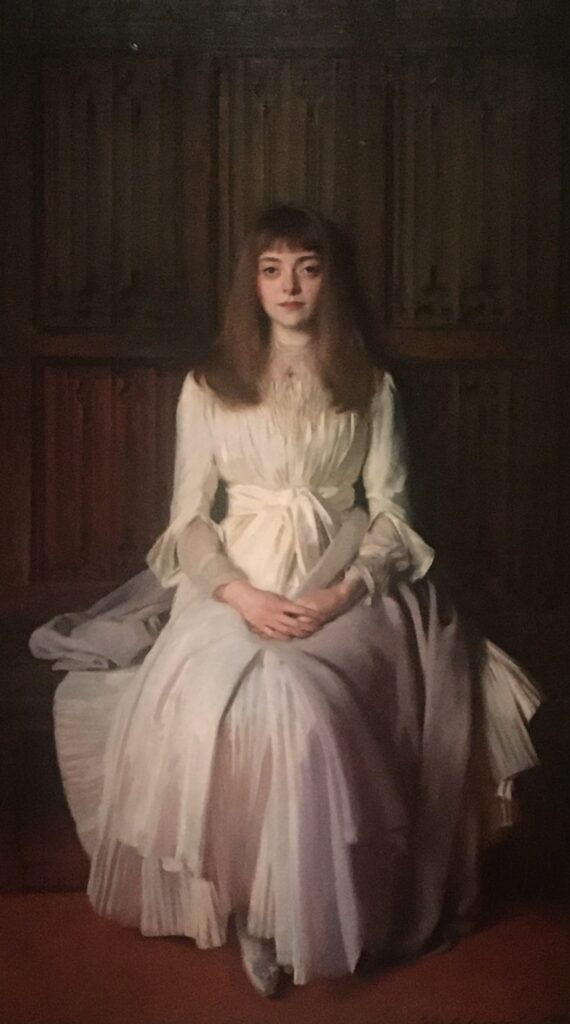

The Exhibit “Fashioned by Sargent” Was on Display in 2024

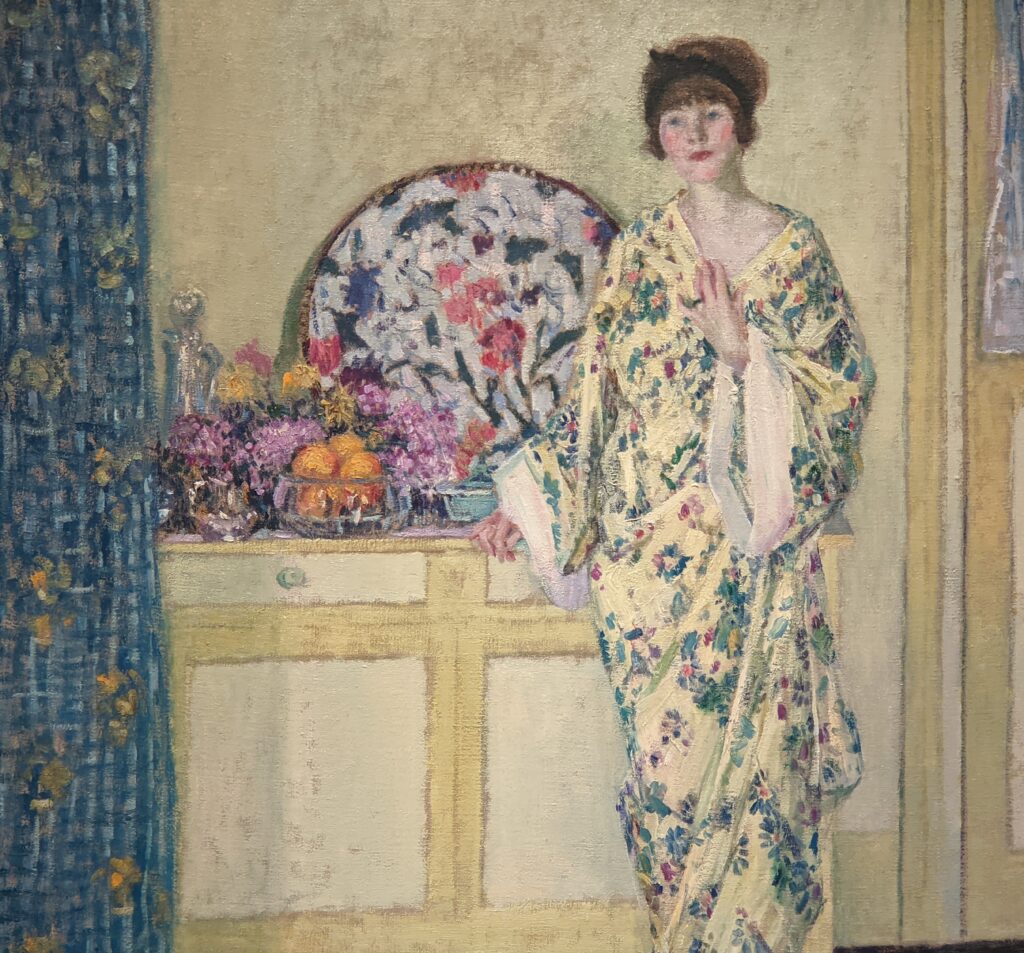

Organized with Tate Britain, the special exhibition entitled “Fashioned by Sargent” explored the painter’s complex relationships with his clients who commissioned portraits. John Singer Sargent often chose what his sitters wore, and he altered details of attire to express the social position, gender identity and distinctive personalities of the men and women he painted. Dozens of period garments, alongside 50 paintings by Sargent, were on display at the MFA Boston through January 15, 2024.

Art of the Americas Wing Inside the MFA Boston & the Museum’s Splendid Permanent Collection

“An Artist in His Studio” (above) is a reprise of the picture-within-the-picture theme Sargent introduced in 1885 when he created “Claude Monet Painting by the Edge of a Wood.” The subject of the artist at work appealed to Sargent, though he typically depicted his colleagues painting outdoors. This painting is exceptional, completed at a time when Sargent was showing a renewed interest in interior scenes. According to the MFA Boston, “Like other such images, Sargent crafted ‘An Artist in His Studio’ with large, vibrant brushstrokes, impasto, and brilliant light. The bravura brushwork belies the painting’s careful creation: Sargent worked tirelessly to compose and build his paintings, adding flashing strokes only at the very end of the process to give the impression of effortlessness and spontaneity.”

Martin Johnson Heade

Winslow Homer

Colonial America & the War for Independence

History buffs will find the finest collection of Colonial-era furniture and paintings at the MFA Boston. One of the turning points during the American Revolutionary War (1775 — 1783) came on the morning of December 26, 1776 after General George Washington led his troops across the frozen Delaware River at night to surprise the enemy’s forces at Trenton, as depicted by Thomas Sully in 1819 in “The Passage of the Delaware” (below). You will notice that Sully calls attention to people of color who participated in the American Revolution by including William Lee, an enslaved man, on horseback at right.

John Singleton Copley

More than 60 paintings by Copley (1738 — 1815) are normally on view at the MFA Boston, including the portrait of “Mrs. Richard Skinner” (below) from 1772.

William Merritt Chase

Mary Stevenson Cassatt

Childe Hassam

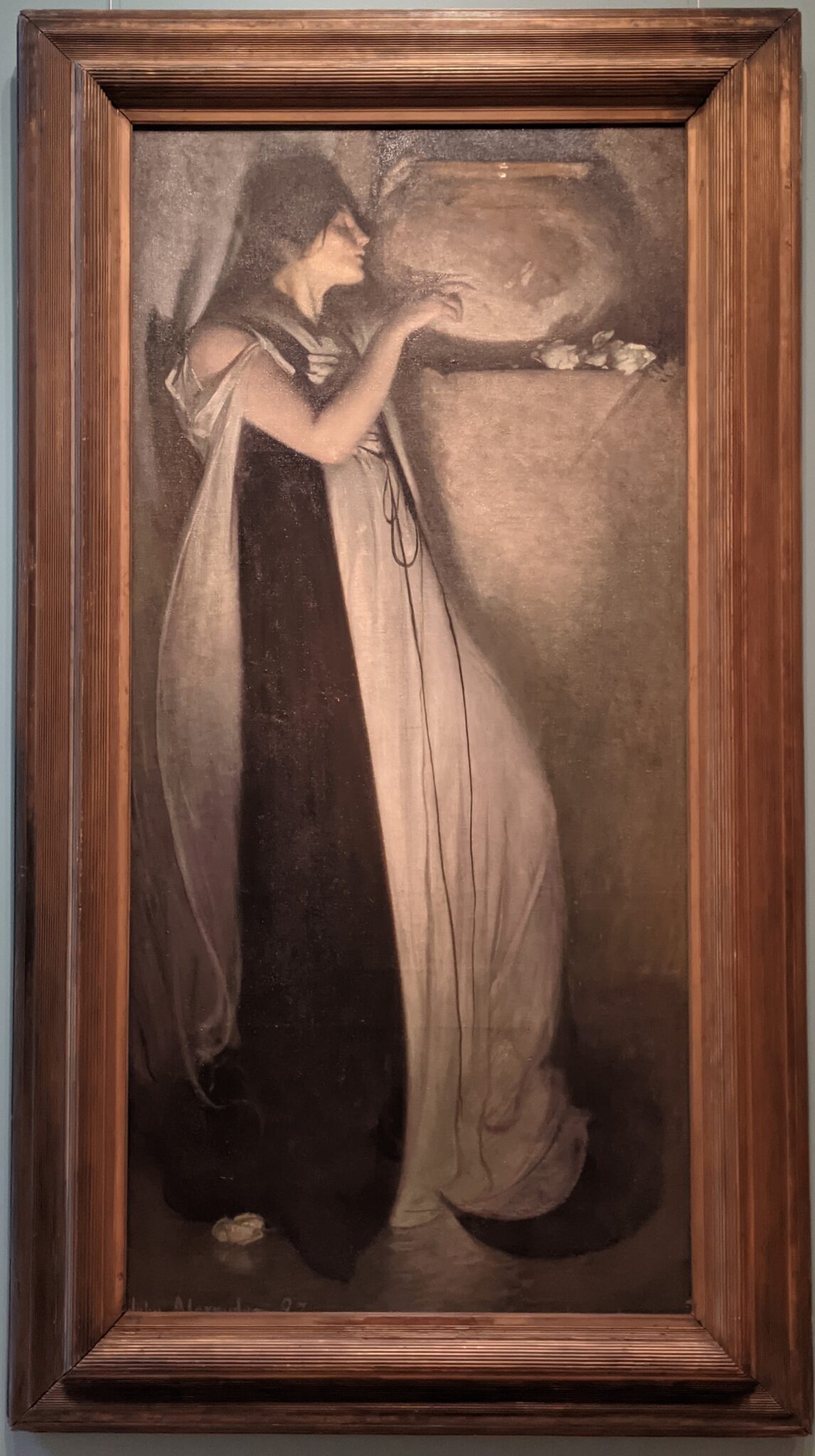

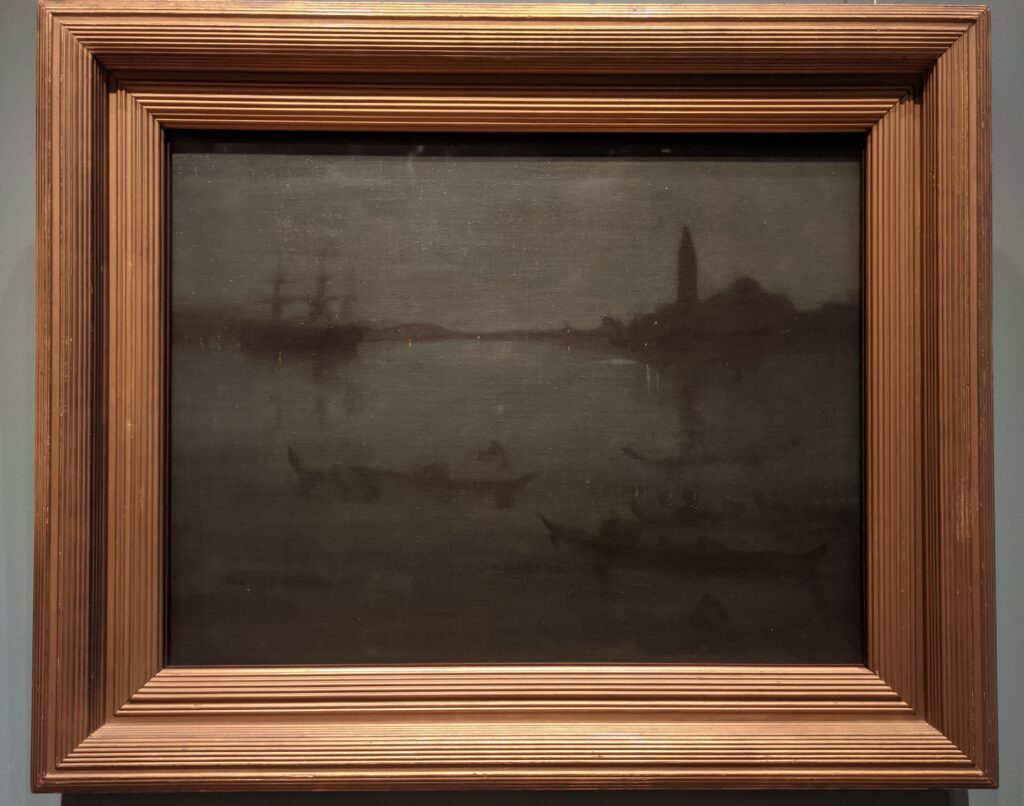

James McNeill Whistler

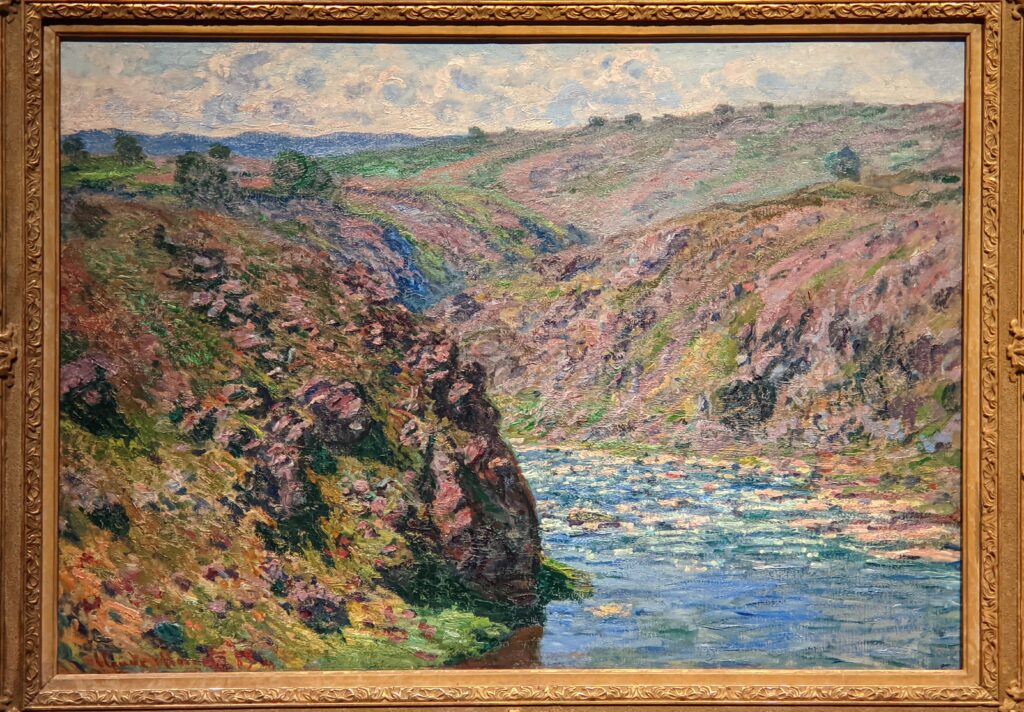

Philip Leslie Hale was among the first American artists to travel to Giverny, France, to work alongside Claude Monet. Beginning in 1888, Hale spent several summers in Giverny. He advised Monet to visit the USA to “try his hand” at painting the rapids at Niagara Falls.

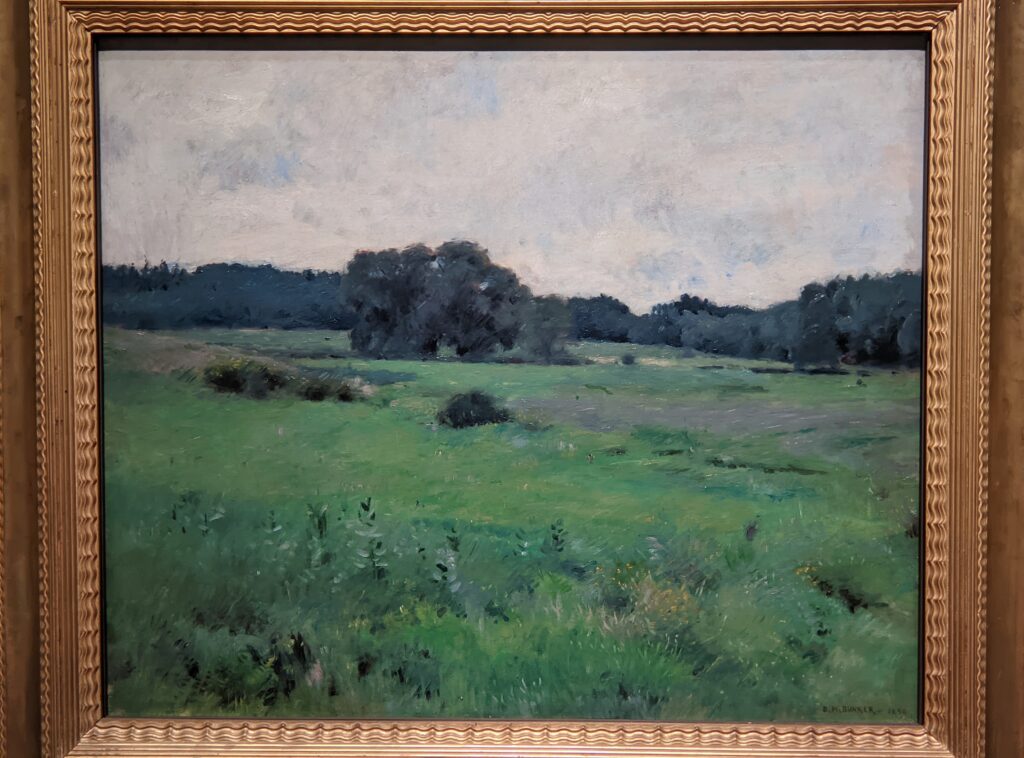

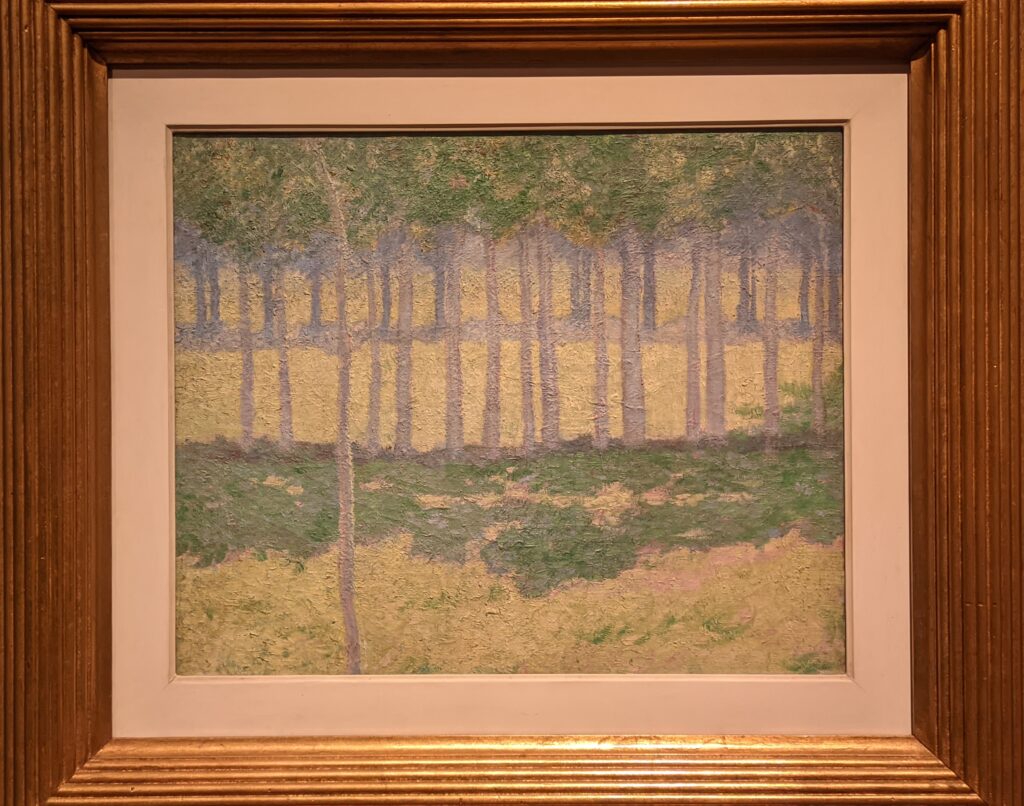

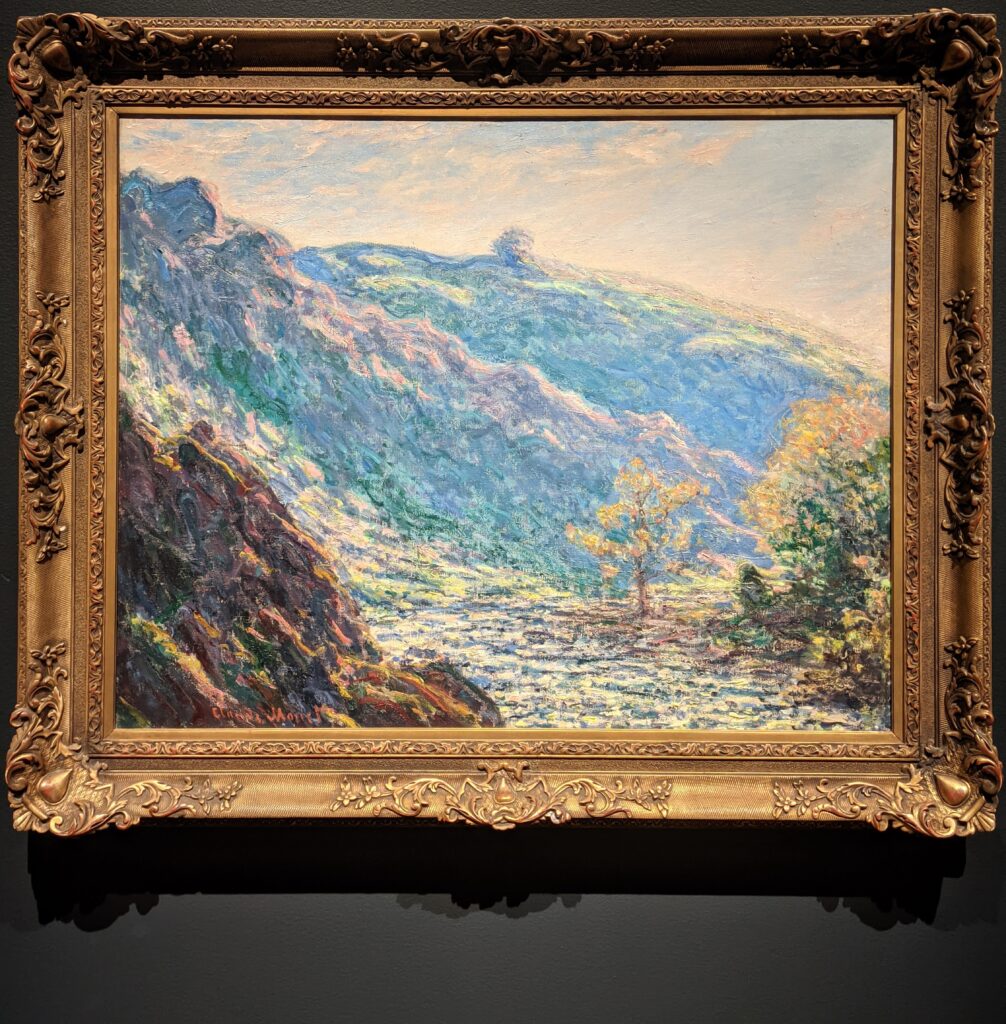

BELOW: Valley of the Creuse (Gray Day), 1889 by Claude Monet

A Superb Collection of Impressionism at the MFA Boston

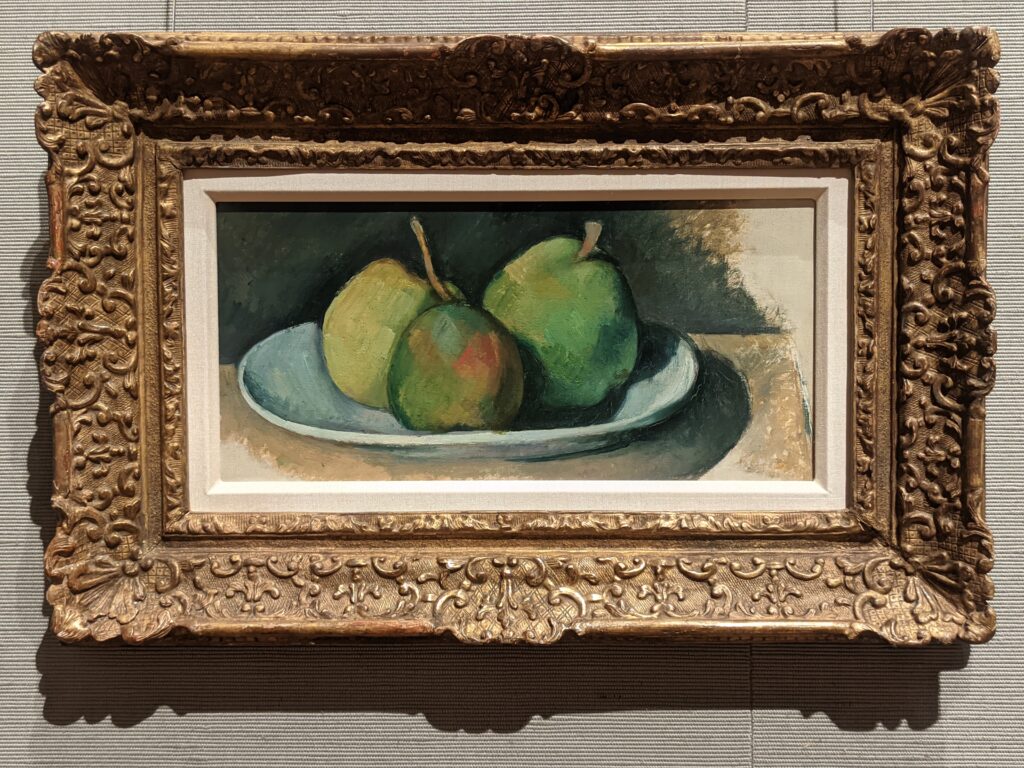

Paul Cézanne & His Influence on Post-Impressionism

Vincent van Gogh

European Art

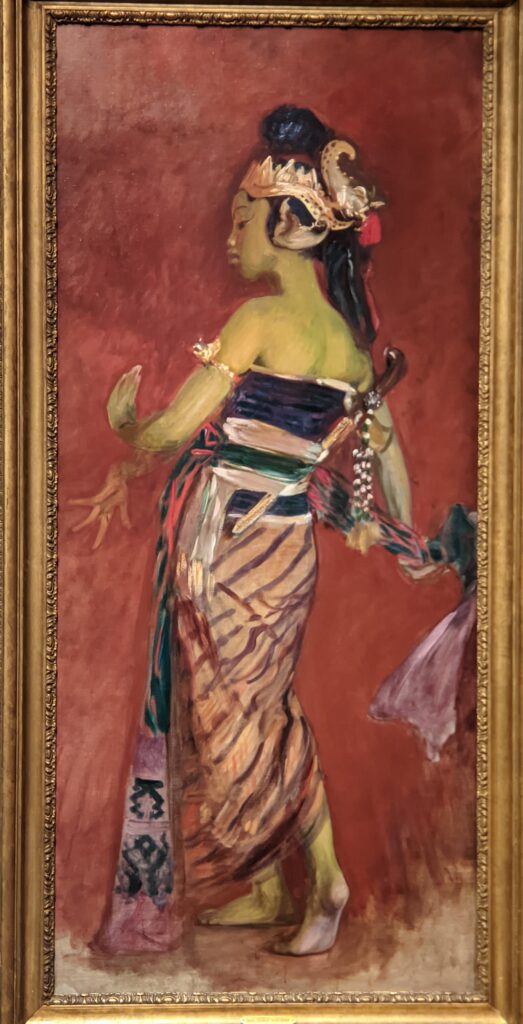

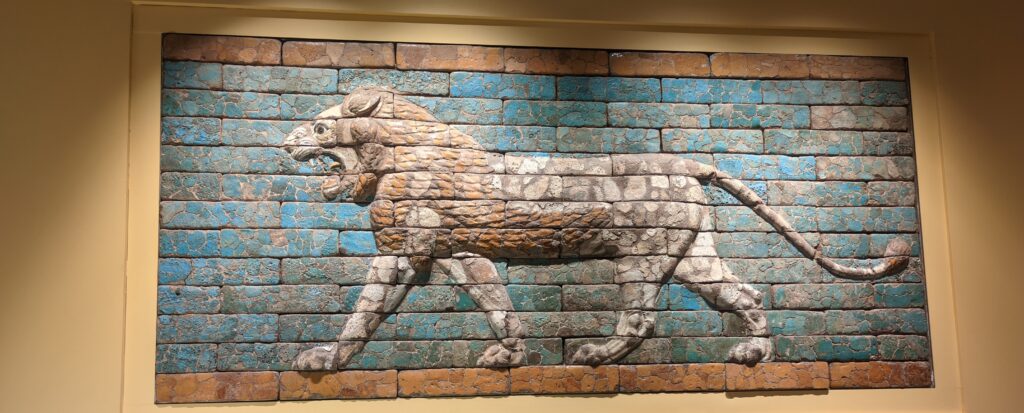

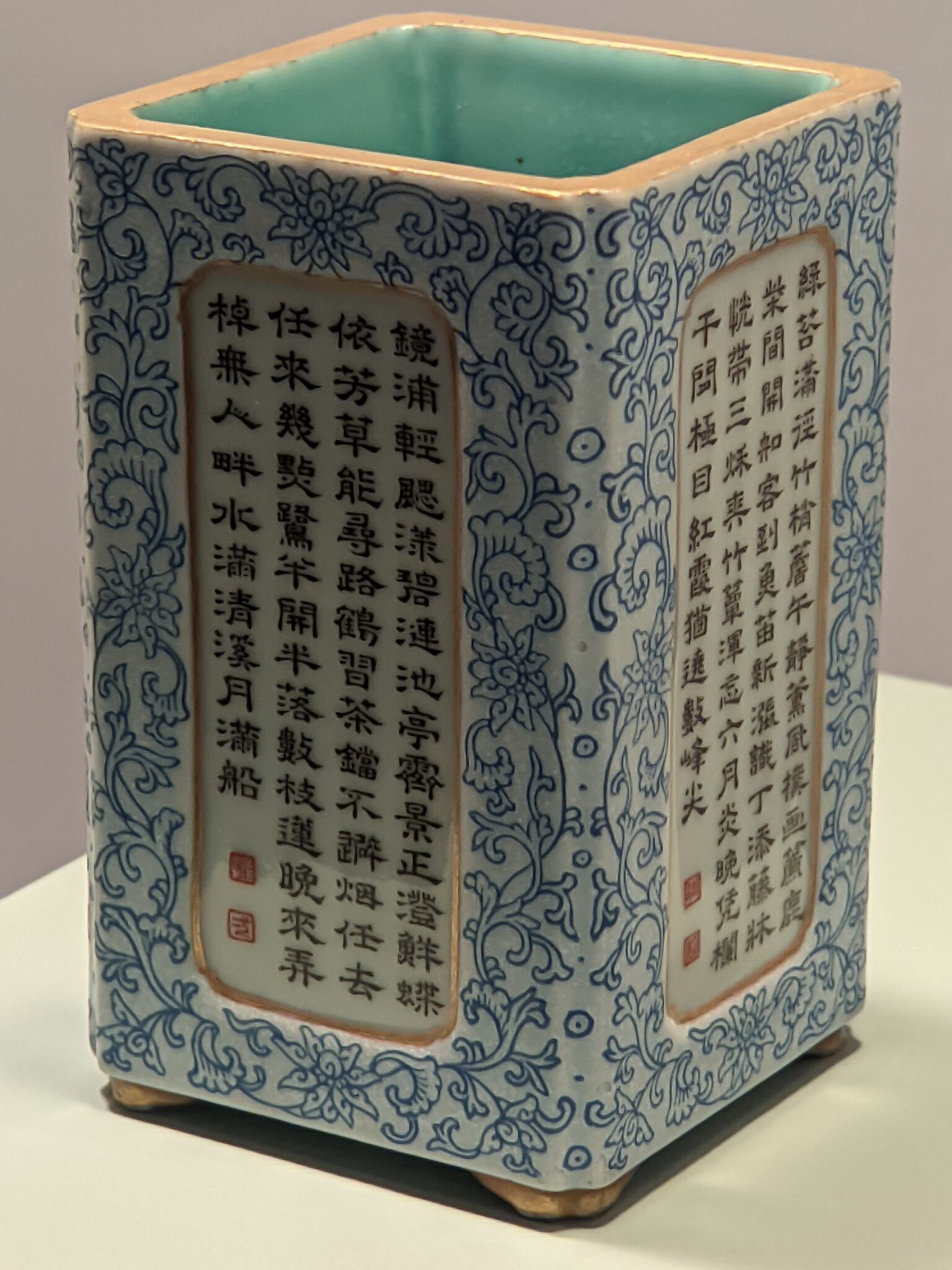

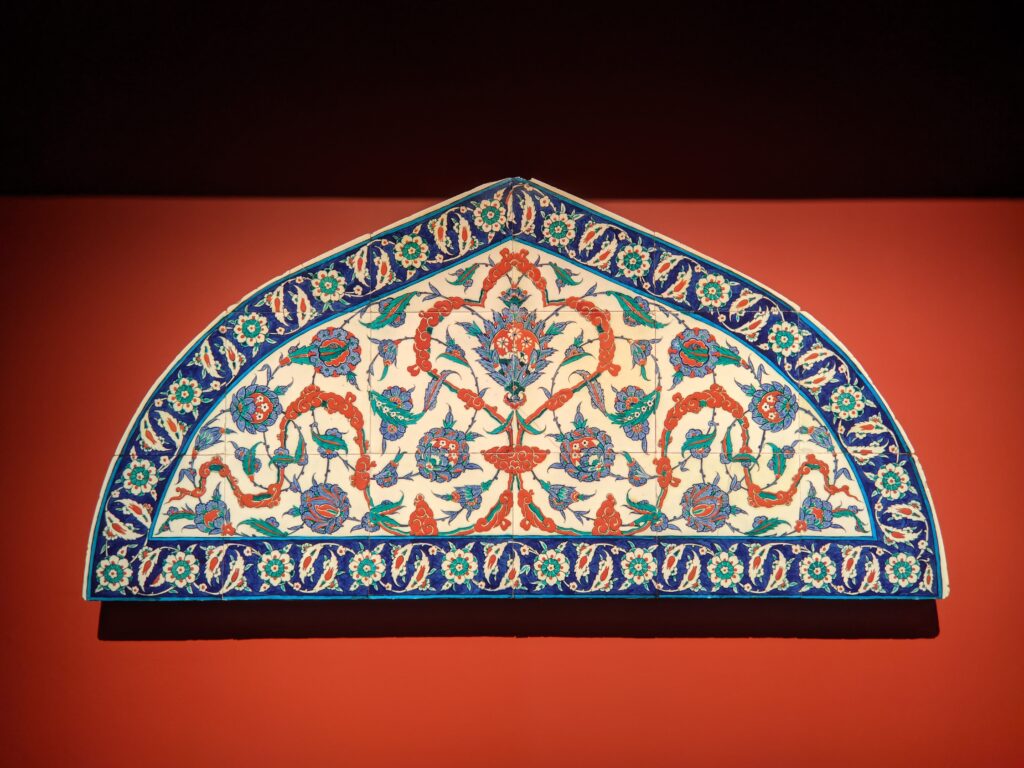

Antiquities, Asian & Islamic Art

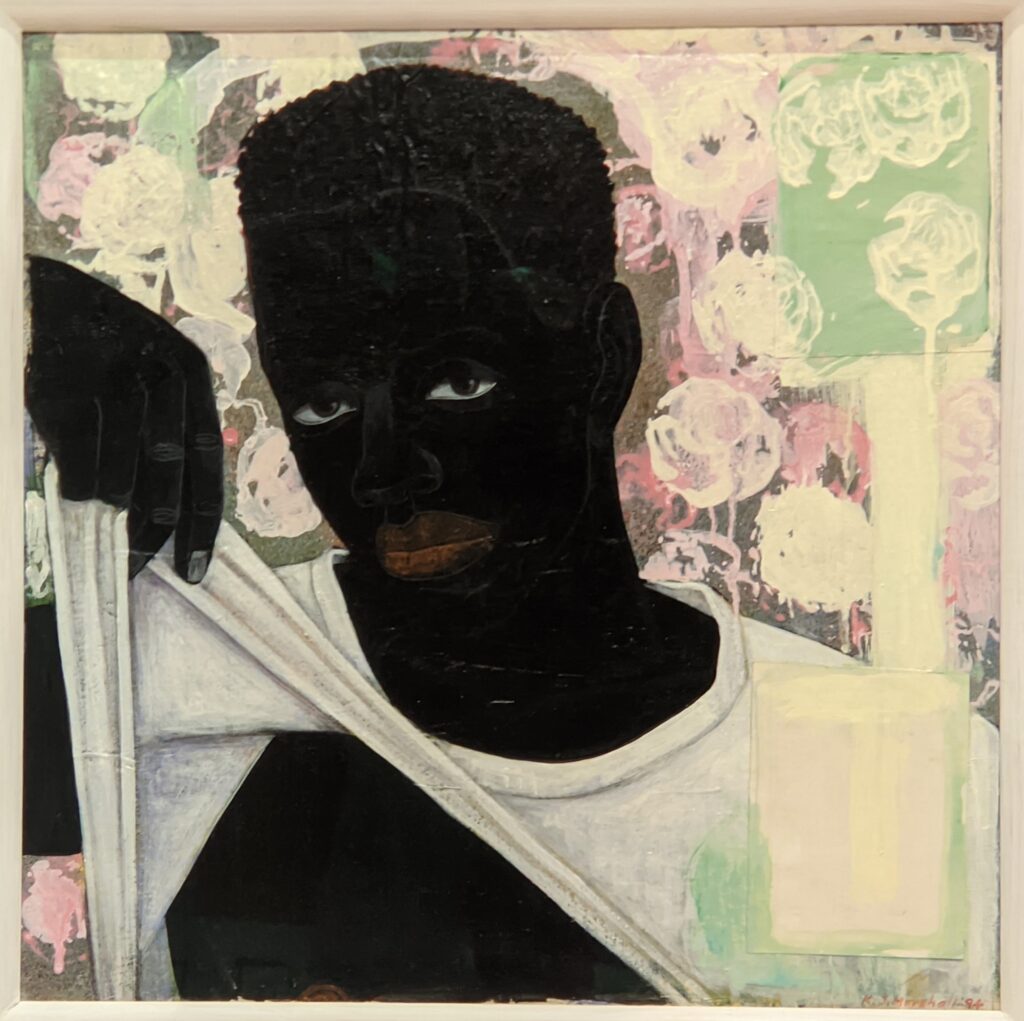

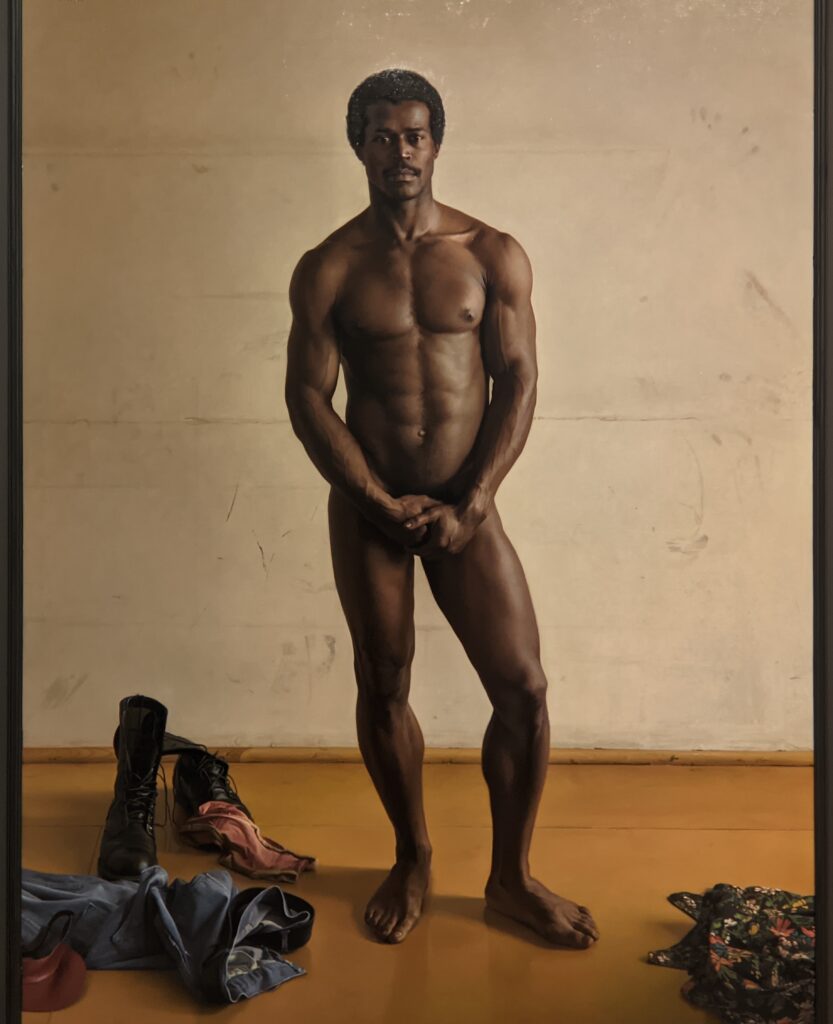

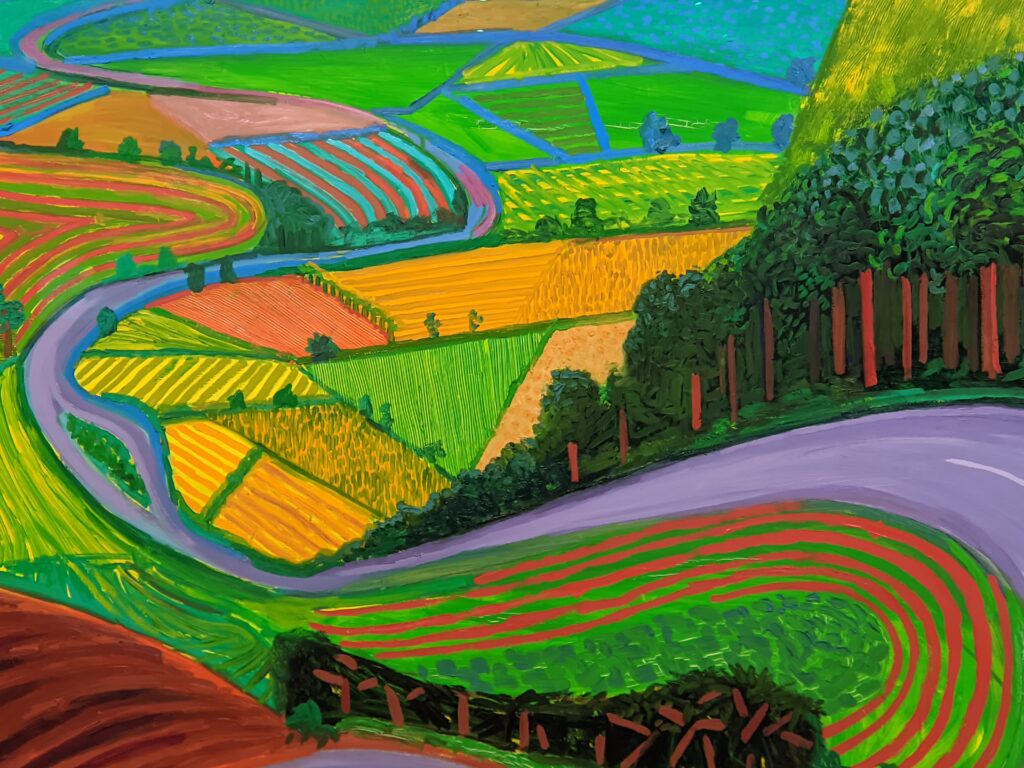

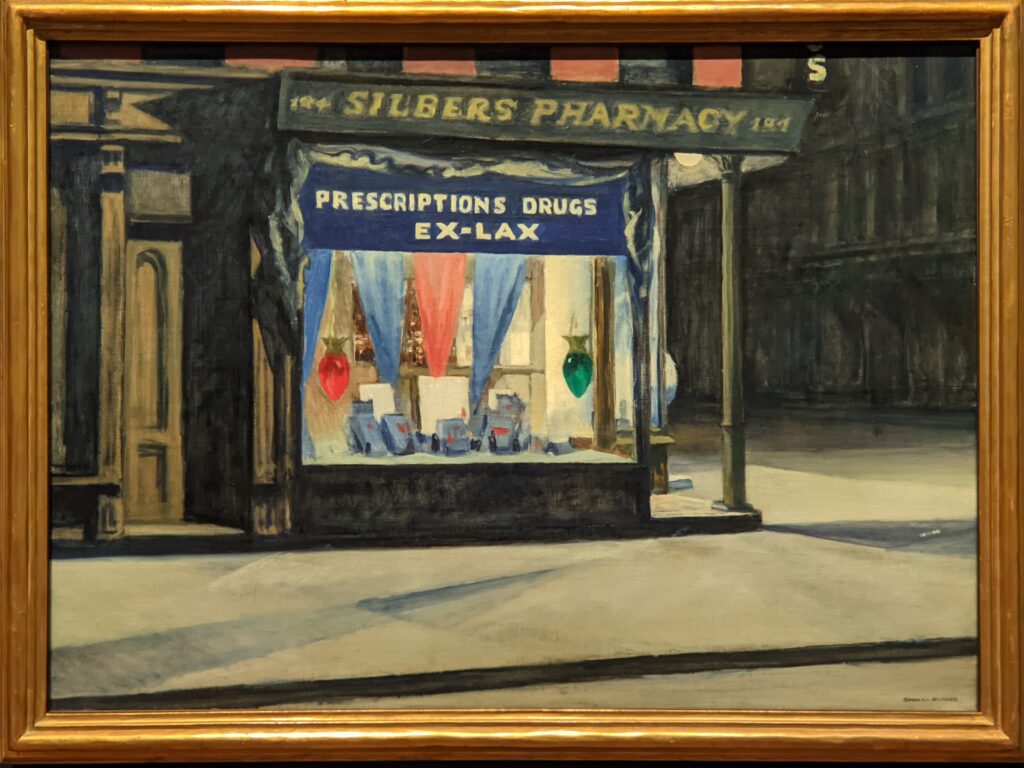

Modern Art at the MFA Boston

Enjoying the City of Boston