The Most Magnificent European Display of Monet & Other Impressionists

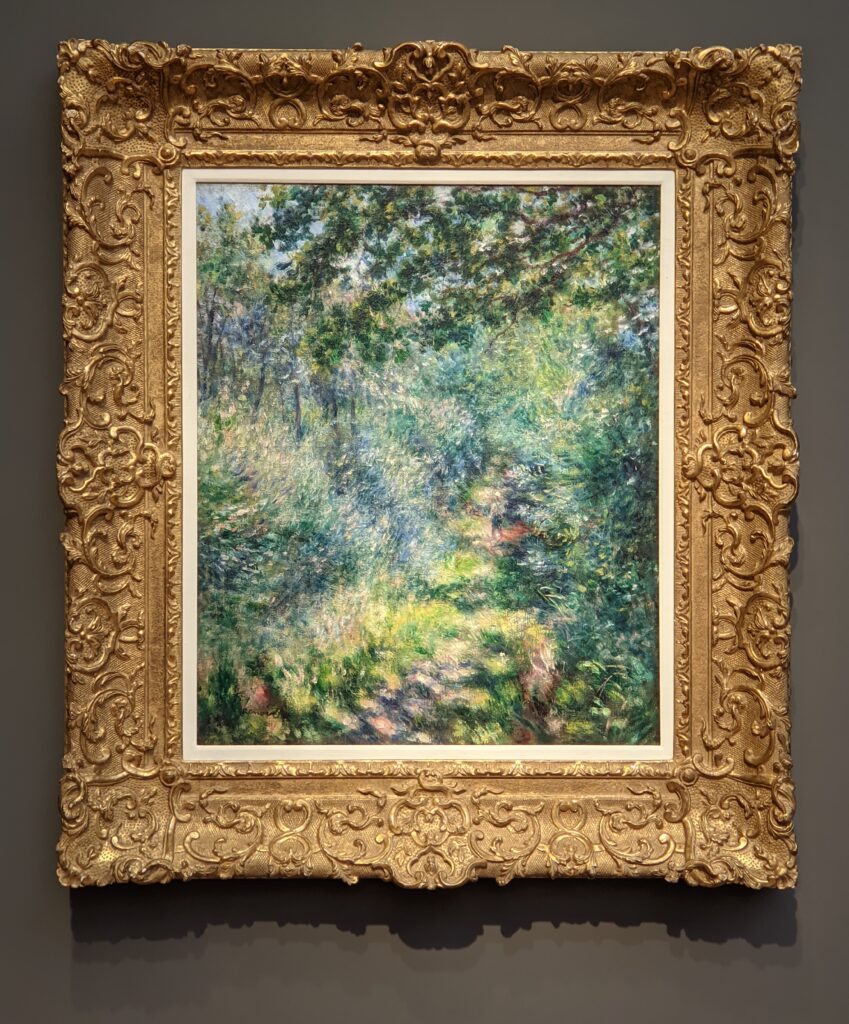

The ambition of Oscar-Claude Monet (1840 — 1926) to capture on canvas the passing of the seasons and the changing of daylight transformed how we perceive nature and led the way to 20th-century modernism. If you have the opportunity to view the Hasso Plattner Collection in Potsdam, Germany, you will be enchanted by Monet’s devotion to painting outdoors and his exploration of light on the lush vegetation surrounding his homes in Argenteuil, Vétheuil and Giverny. This amazing collection housed inside the Museum Barberini also visually articulates the major contributions made by other Impressionist painters, most notably Gustave Caillebotte and Alfred Sisley, as well as those who provided the embryonic inspiration for their movement.

Eugene Boudin, Berthe Morisot & Auguste Renoir

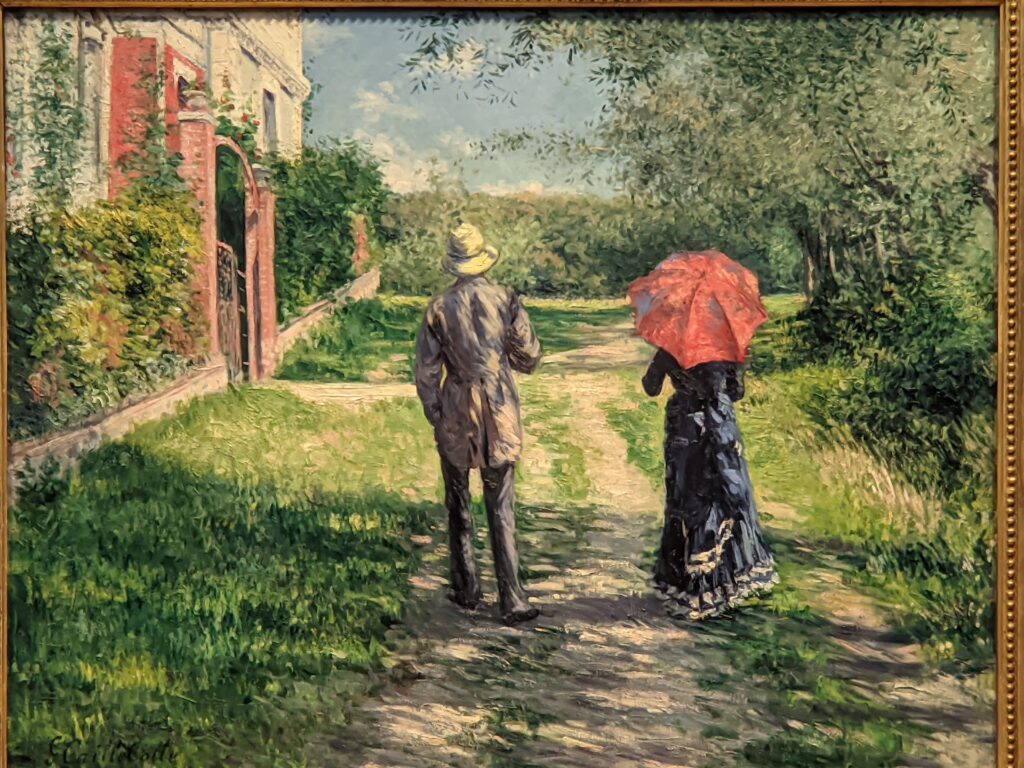

Gustave Caillebotte

Caillebotte was unique among the Impressionists in several respects. Many of his paintings employ an unusually high vantage point and are finished in a more realistic style with a less vibrant palette than his contemporaries.

During his lifetime, Gustave Caillebotte was better known as a patron of the arts. In fact, he was virtually forgotten as an influential artist until the 1950s when his descendants began to sell the large family collection of his art. After the Art Institute of Chicago acquired the masterpiece “Paris Street, Rainy Day” in 1964, Caillebotte’s body of work was critically reassessed and appreciated. The paintings by Caillebotte in the Hasso Plattner Collection (pictured below) demonstrate why such recognition is well-deserved.

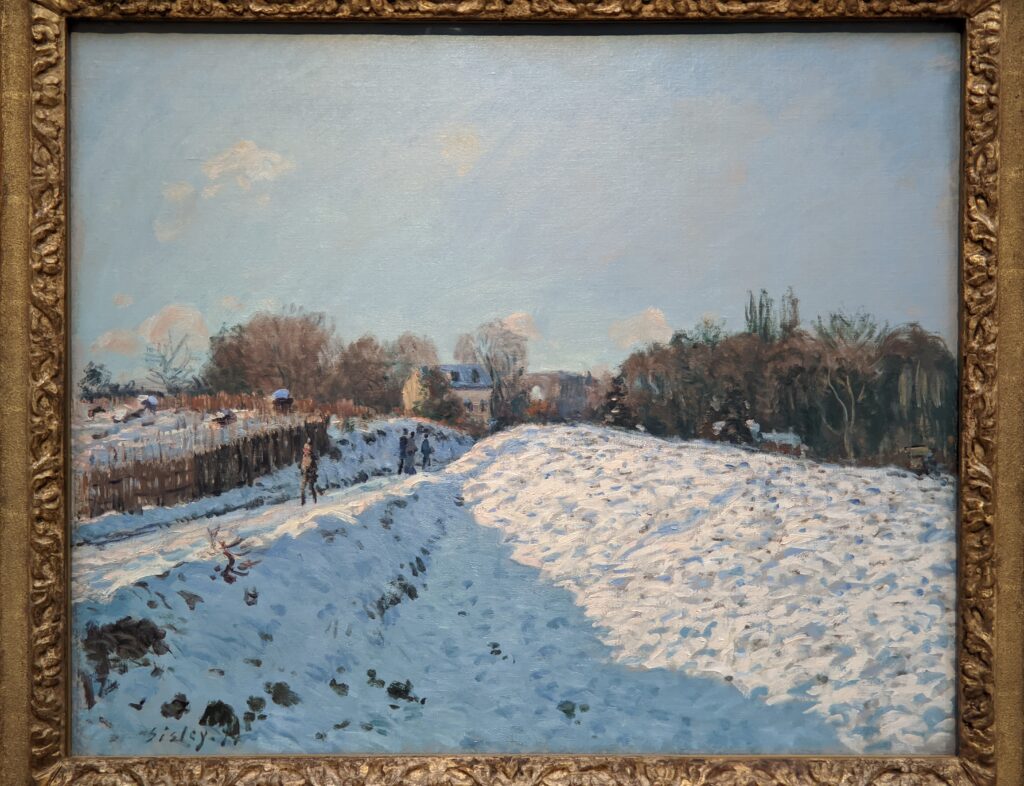

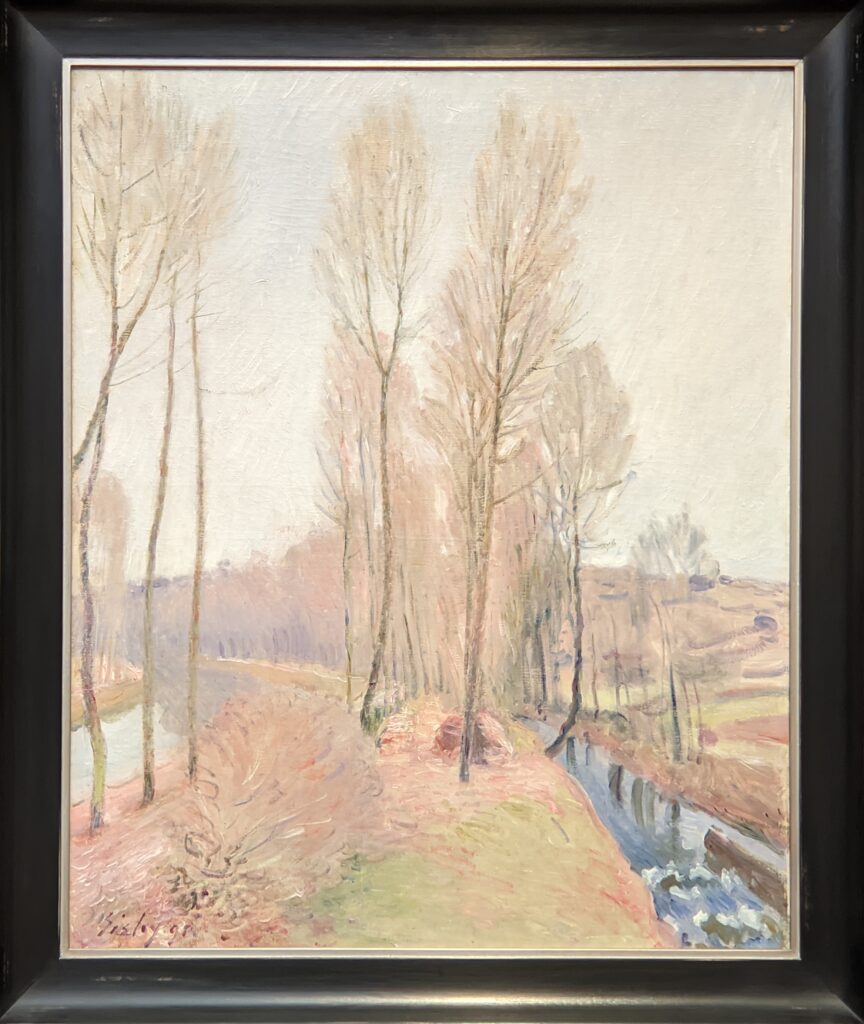

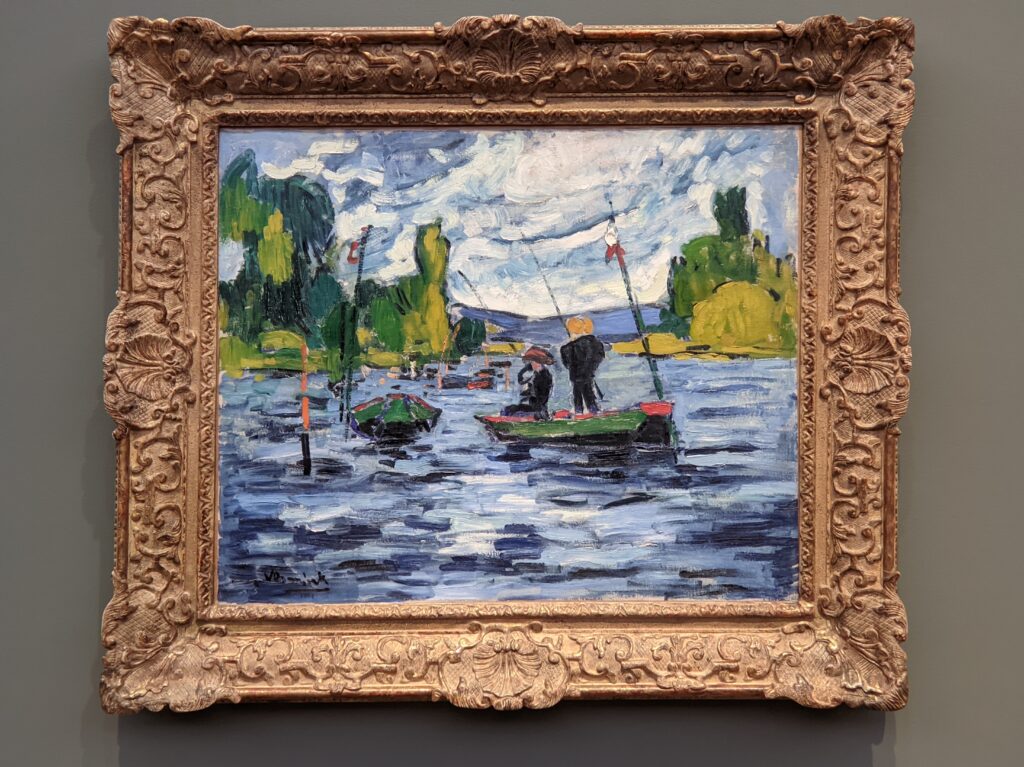

Alfred Sisley

Among the core Impressionists, Sisley was the most consistent and pure in his dedication to painting landscapes en plein air. In marked contrast with Monet (whose work his resembles in subject matter and style), Sisley never sought the brilliantly colored scenery of the South of France and Venice, or the drama of roaring ocean currents along the coastline. With a subdued palette, Sisley focused on landscape painting more consistently than any other Impressionist. Unlike Renoir, Pissarro, Cézanne and Gauguin, Alfred Sisley found that Impressionism alone fulfilled his artistic needs. His oeuvre powerfully invokes atmosphere and epitomizes Classic Impressionism.

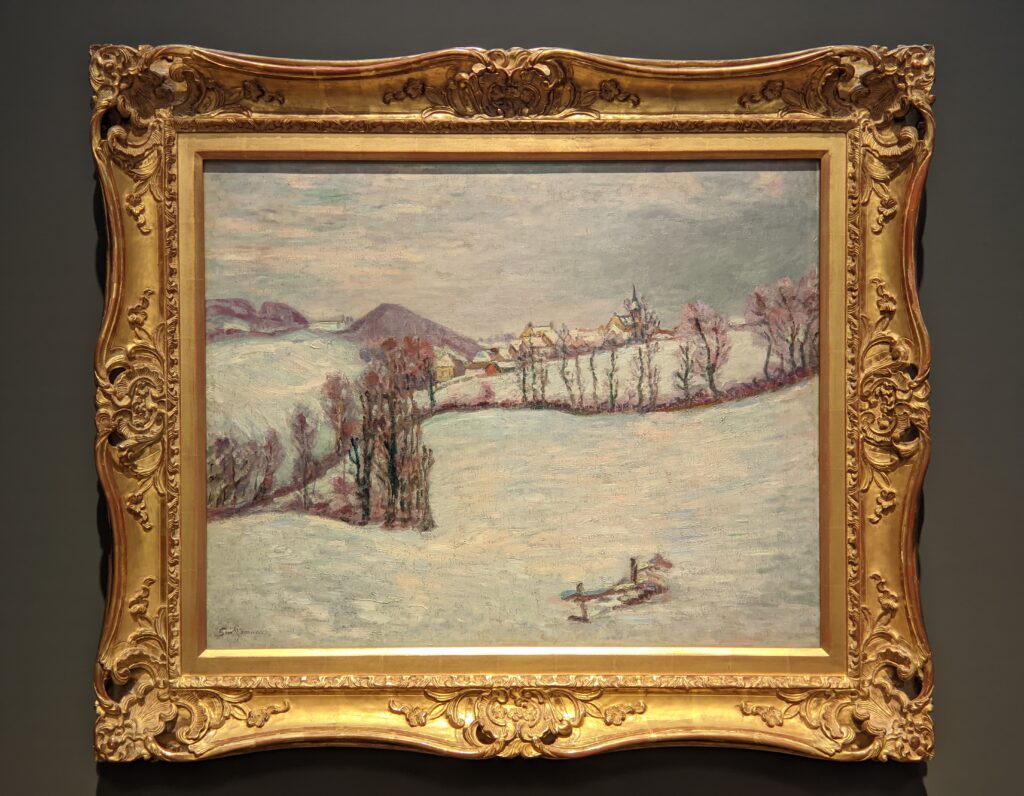

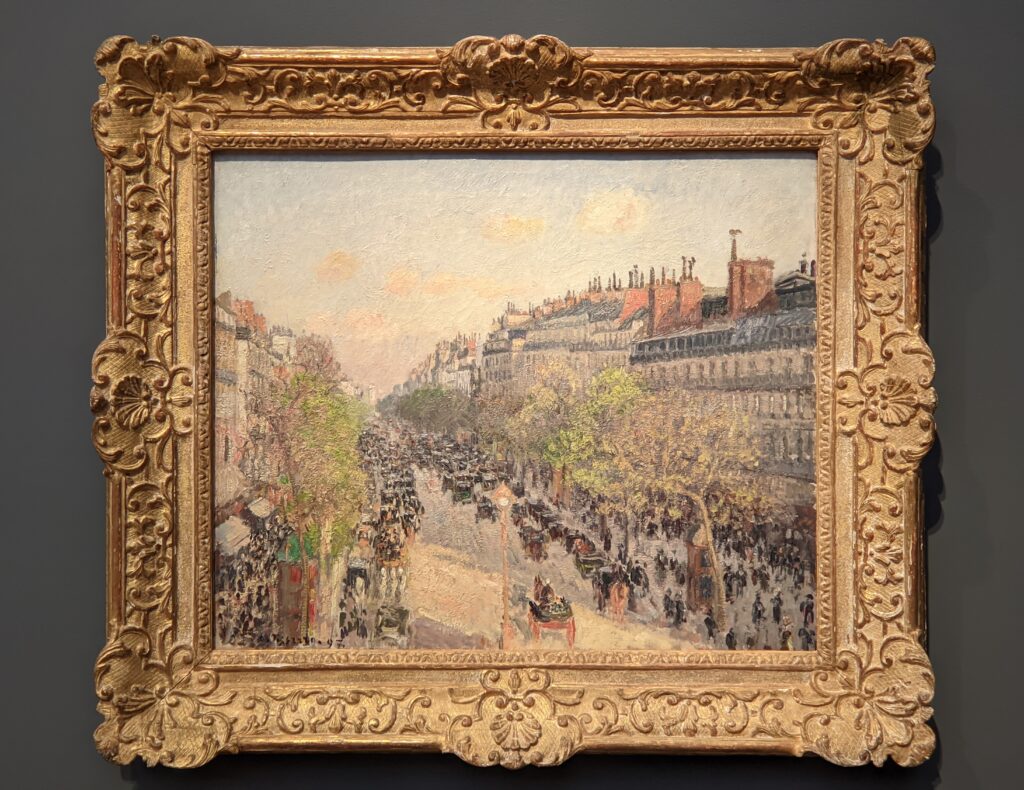

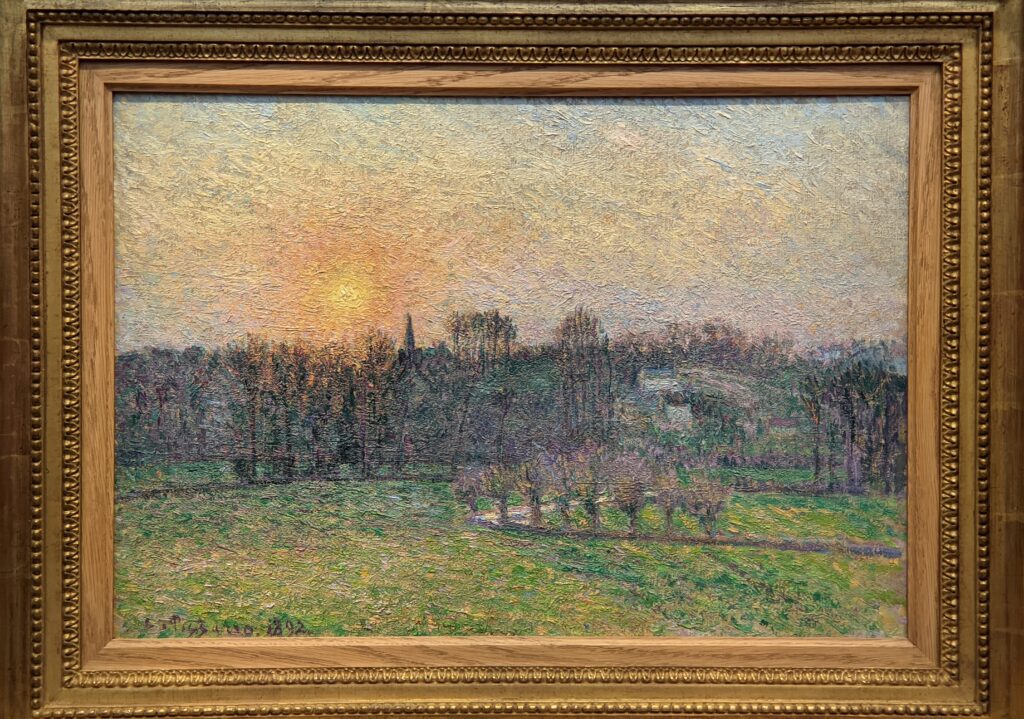

Camille Pissarro, Armand Guillaumin, Henri Le Sidaner & Gustave Loiseau

Pissarro admired the work of Charles-François Daubigny and was tutored by the equally great Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and we feel obliged to point out that during the period between 1860 and 1885 the mercurial Camille Pissarro went on to surpass both of these magnificent landscape painters. History credits Pissarro with making groundbreaking contributions to both the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements, and as the only artist to have shown his art in all eight of the independent Impressionist Exhibitions, held in Paris between 1874 and 1886. Pissarro acted as a father figure not only to all of his colleagues within Impressionism, but to all five of the major Post-Impressionists — Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Pissarro met Seurat and Signac in 1885 and for four years practiced their more scientific theory of Neo-Impressionist painting, which Pissarro abandoned by 1990. He continued to paint until his death in 1903 at the age of 73.

The Eighth and final Impressionist Exhibition signaled the end of Classic Impressionism. By 1886 Pissarro had left the movement, though he did participate in the Eighth Exhibition (along with Georges Seurat and Paul Signac) by presenting Pointillist compositions. Monet, Renoir, Sisley and Caillebotte did not participate, and the only Impressionist works displayed were by Morisot, Gauguin and Guillaumin. Over time, even Guillaumin distanced himself from the thin brush strokes, sense of movement, changing light and open composition which once defined Impressionism {see Winter in Moret by Sisley, above}.

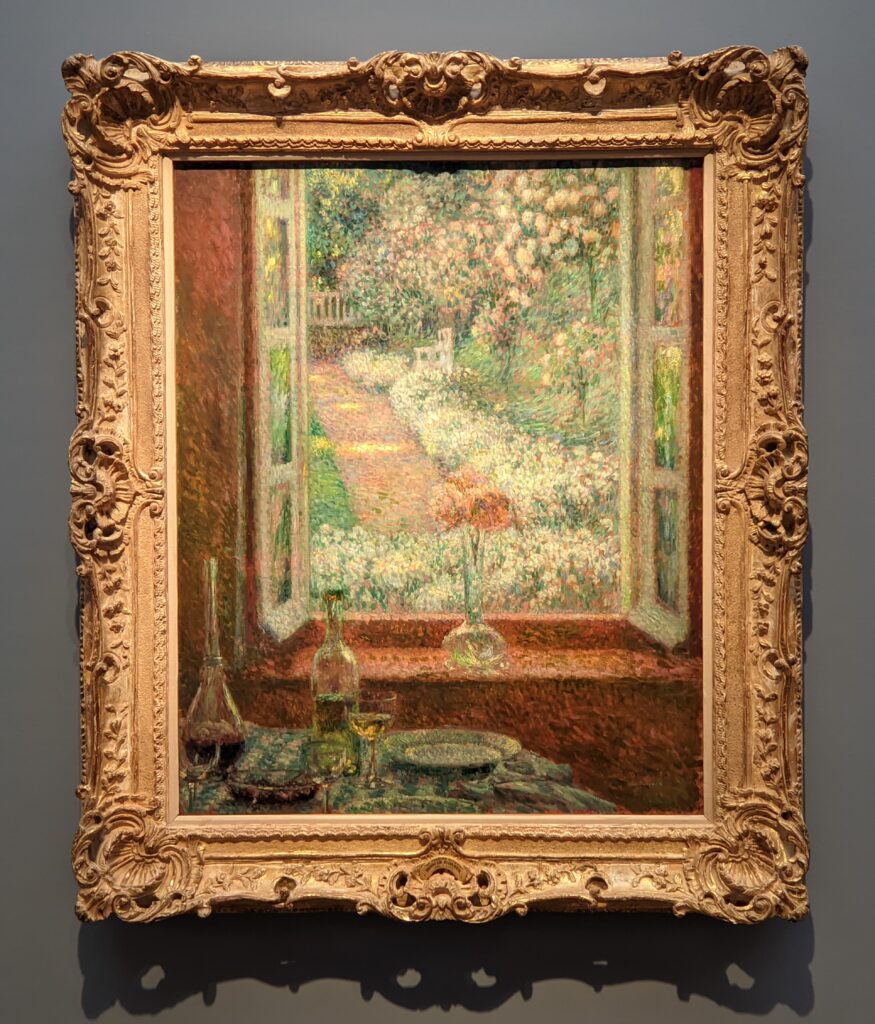

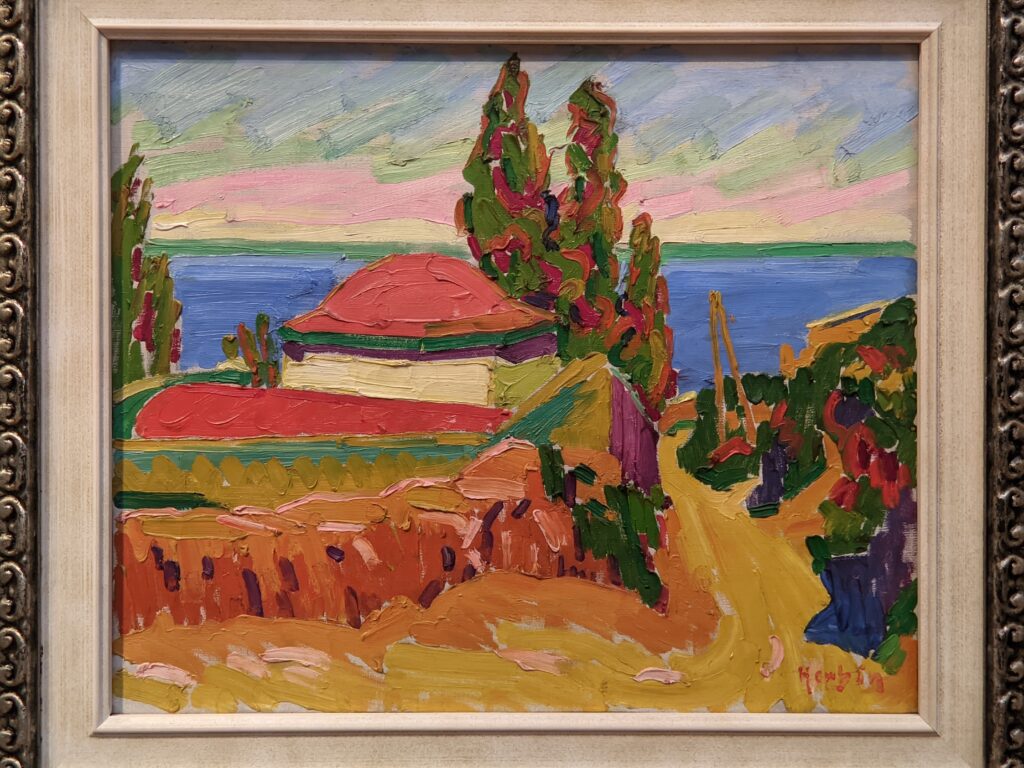

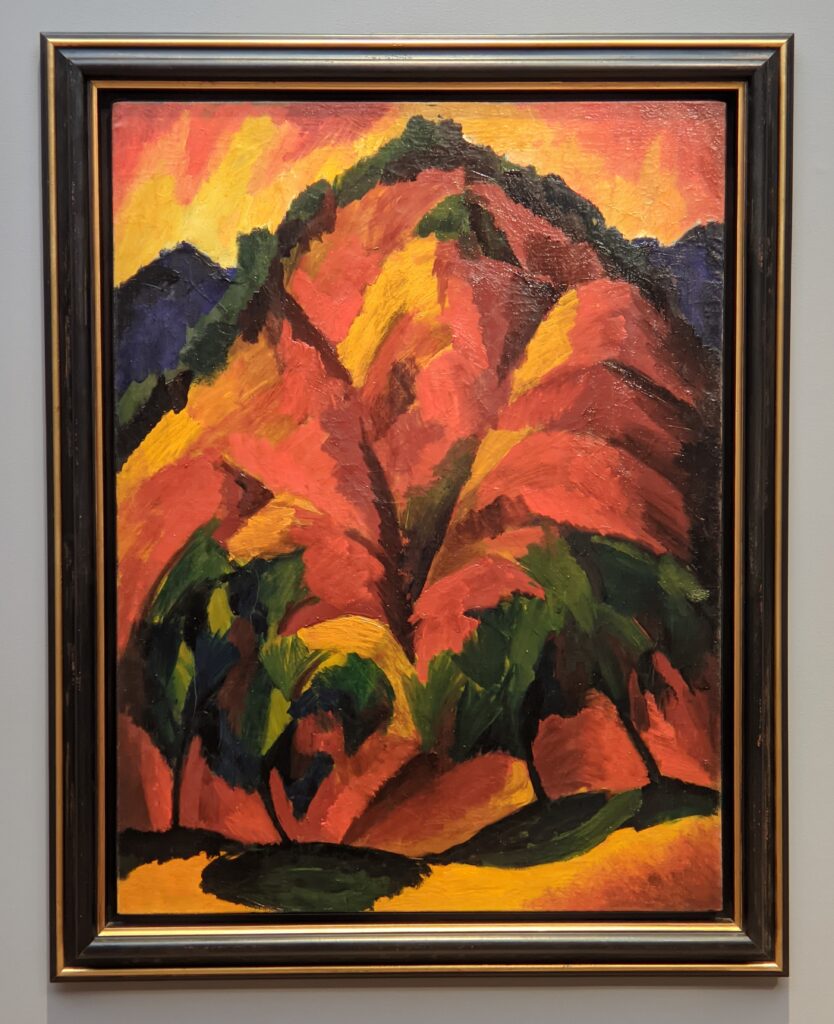

Guillaumin’s strong color combinations, static subject matter, and emphasis on mood and contours — as seen in View of Puy de Dôme, below — are signs of movements to come over the next two decades. The style of Henri Le Sidaner and Gustave Loiseau contained elements of both Impressionism and Pointillism.

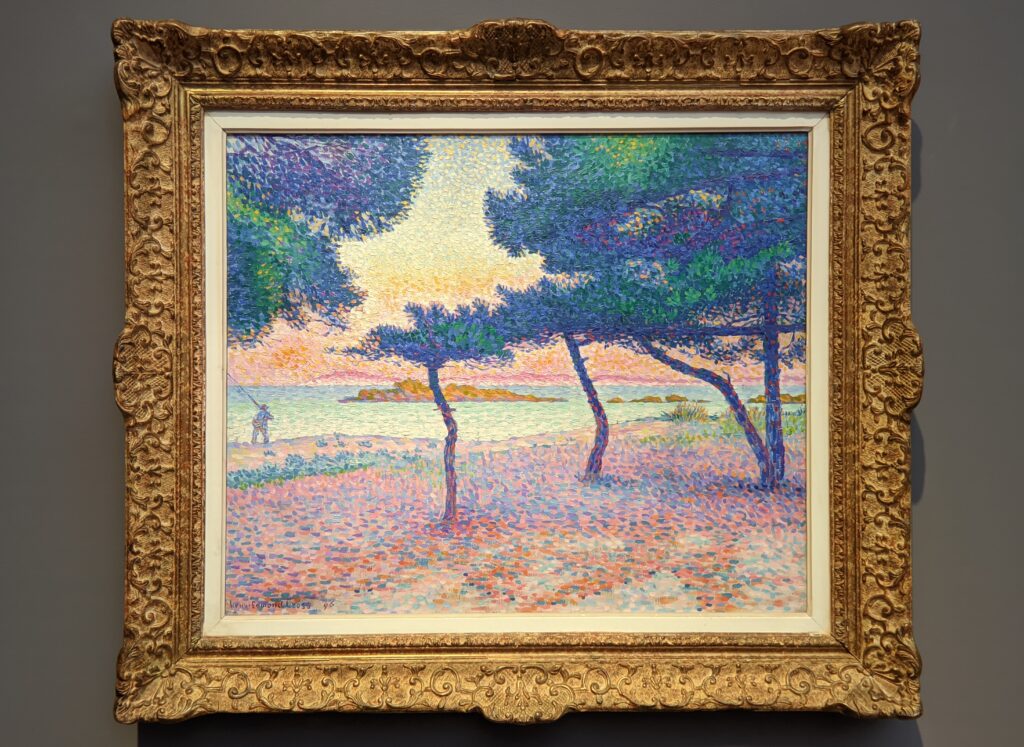

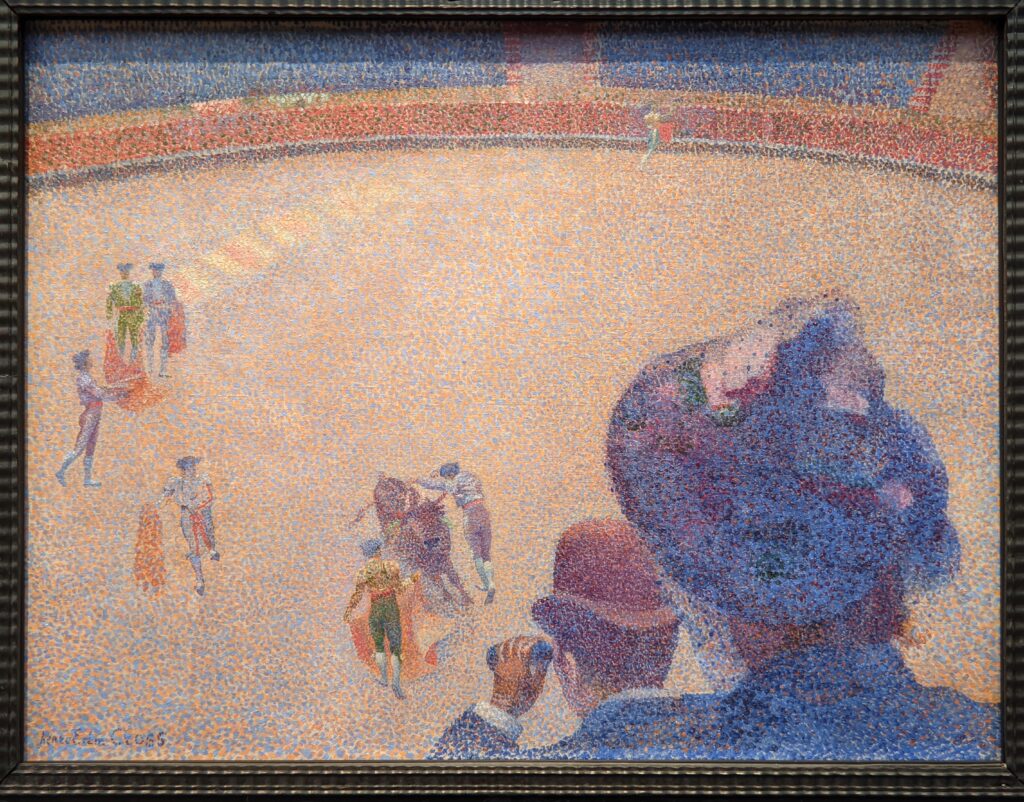

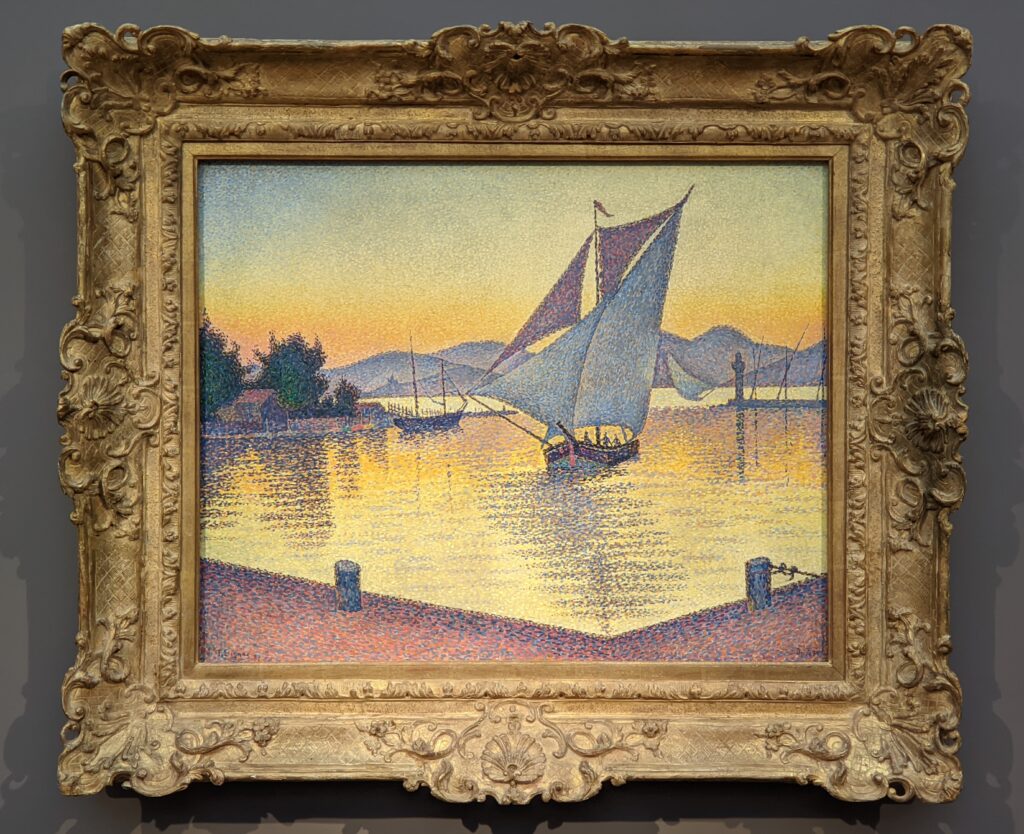

Signac & Pointillism

Paul Signac was studying architecture when he decided to become an artist after attending an exhibition of paintings by Monet. He met Monet and Georges Seurat in 1884, and was impressed by Seurat’s theory of colors and scientific working method in which brushstrokes were replaced with small dots of pure color intended to blend not on the canvas but in the eye of the viewer.

The Impact of Fauvism

Raoul Dufy, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck & Auguste Herbin

Monet & Cézanne Revealed the Path Toward Modernism

Even Pablo Picasso embraced the path defined by Monet {see Boulevard de Clichy, below} when he arrived in Paris in the autumn of 1900. Monet ventured outside the academies and studios to paint nature as he perceived it. Paul Cézanne examined Impressionist forms of expression in order to derive a new pictorial language, and in the process abandoned perspective. Cézanne used planes of color and small, repetitive brushstrokes that build up on his canvases to form complex fields and images. Through Monet’s intensive examination of changes in light throughout the day (and during different seasons) combined with Cézanne’s new design method of deconstructing the Impressionist color modulation and space principles, these two men built a bridge between Impressionism and the 20th-century movements of Fauvism and Cubism.

Claude Monet — A Key Precursor to Modernism

Previous Exhibitions at the Museum Barberini

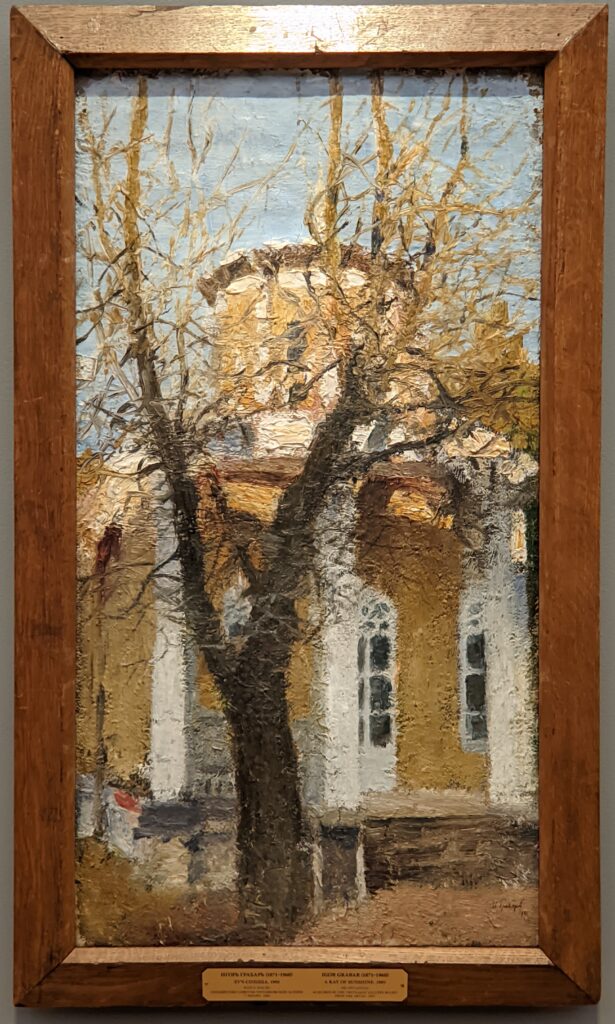

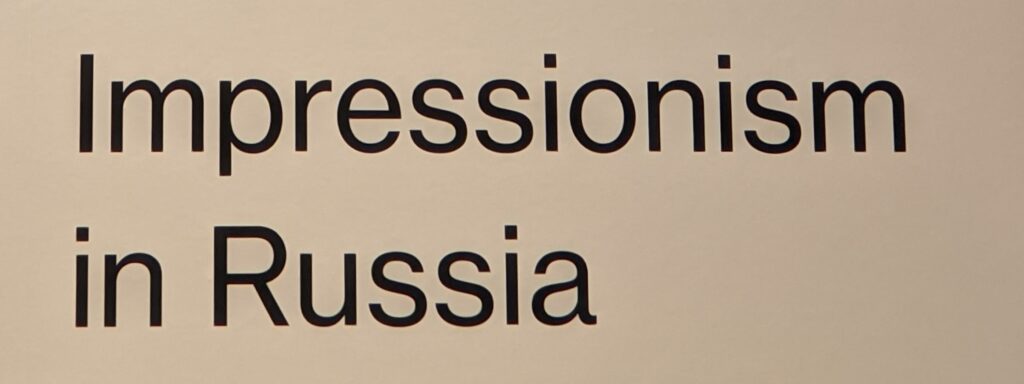

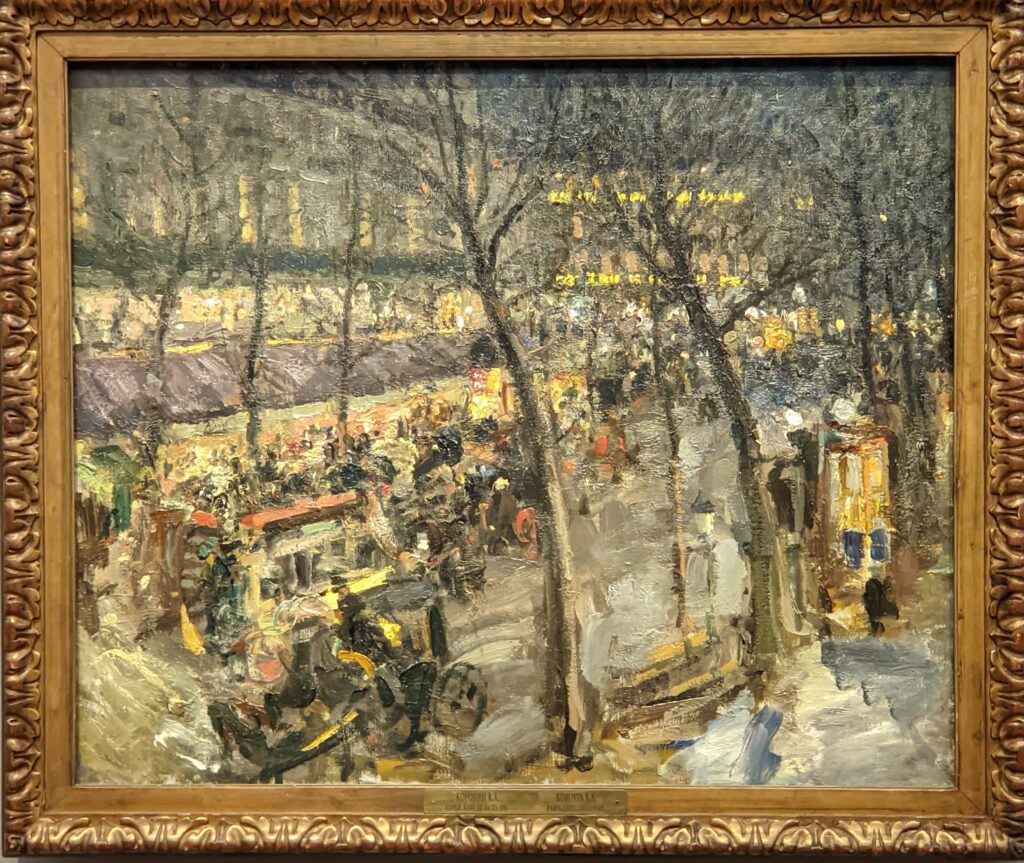

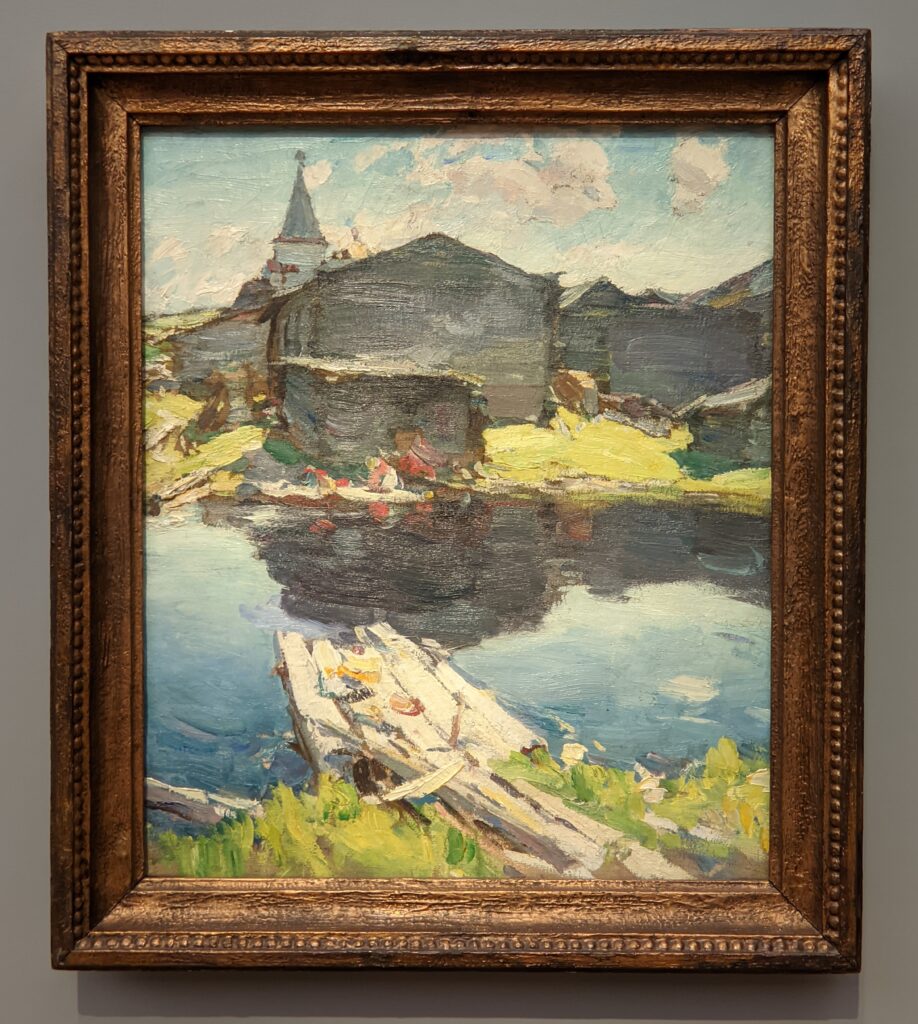

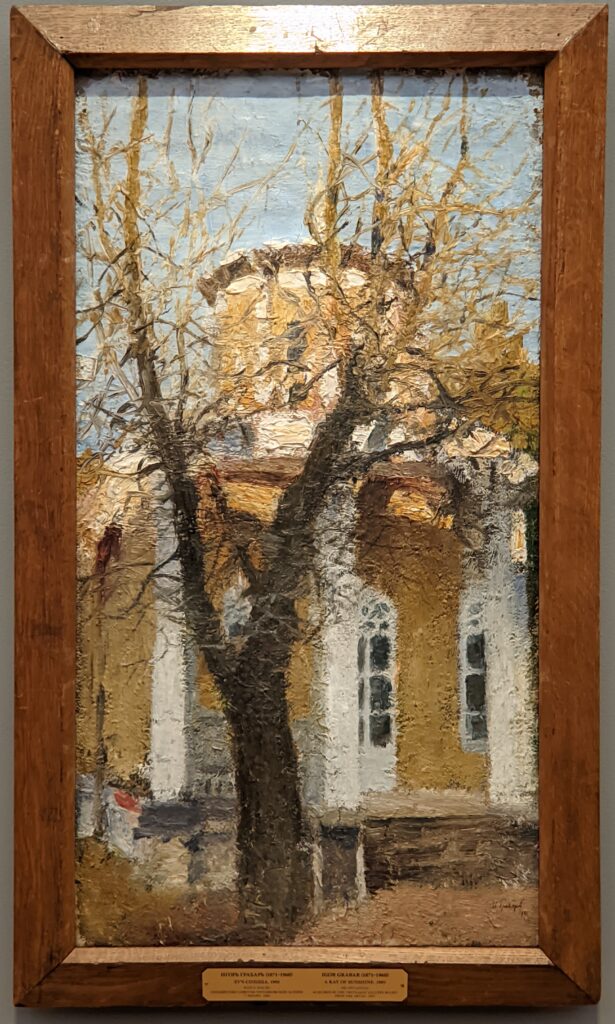

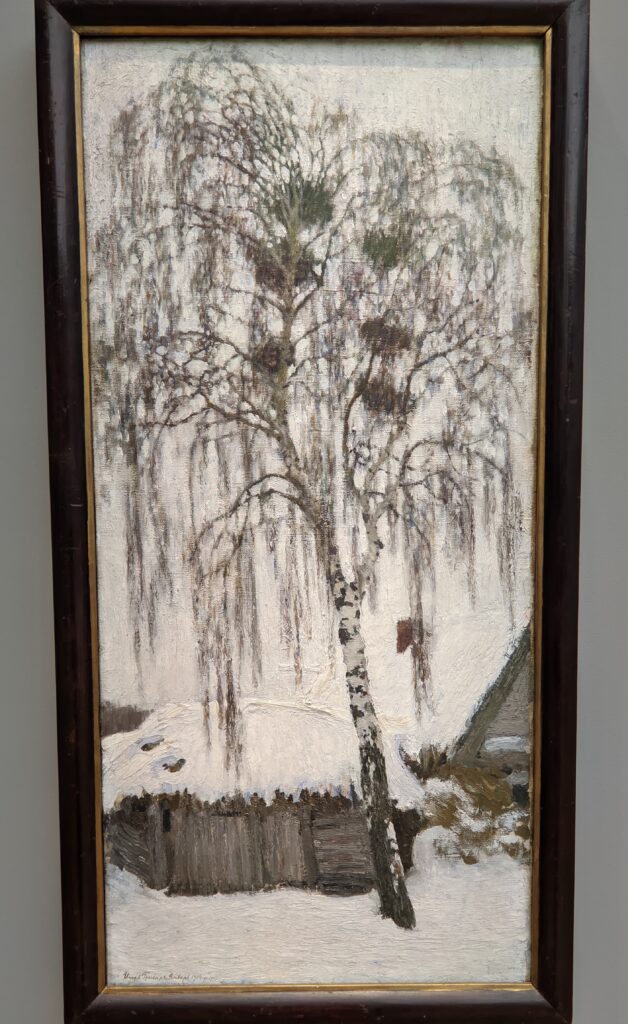

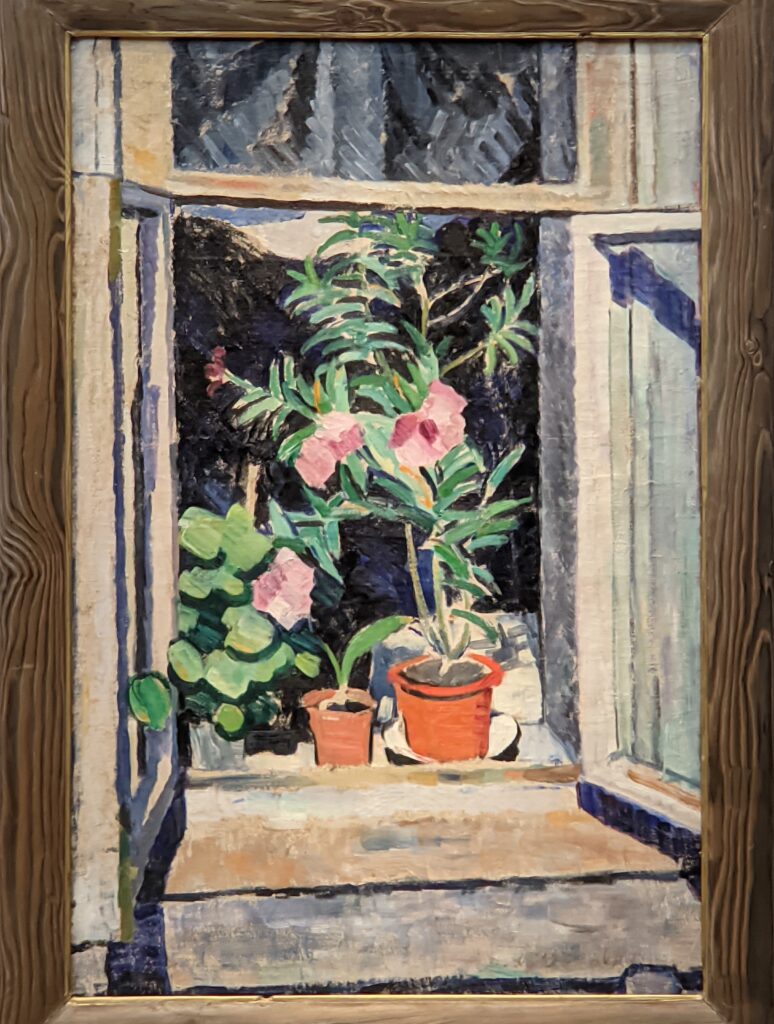

“Impressionism in Russia: Dawn of the Avant-Garde” held from August 2021 through January 2022 brought over 80 works of art to Potsdam from prestigious collections including The State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, considered the world’s foremost depository of Russian fine art. Beginning in the 1860s, the city of Paris attracted painters from the academies in St. Petersburg and Moscow. This eye-opening spectacle (organized by the Barberini in cooperation with the Tretyakov) showed how the Impressionists’ practice of painting outdoors made landscapes popular across Europe, leading to a new artistic freedom that transformed Russian art from Realism to Modernism.

Ilia Repin (1844-1930)

Konstantin Korovin (1861-1939)

Abram Arkhipov (1862-1930)

Valentin Serov (1865-1911)

Sergei Vinogradov (1869-1938)

Monet’s Inspiration was Felt in Russia

While many French Impressionists depicted contemporary life in Paris, exploring the visual connection between balconies and the architecture of grand modern boulevards, many Russian painters followed the lead of Claude Monet by venturing into the countryside to capture nature and leisurely activities in summer residences.

Stanislav Zhukovsky (1873-1944)

Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962)

“Monet: Places” — Where Monet Chose to Live and to Paint

Claude Monet’s painted canvases were the subject of the exhibition “Monet. Orte” in 2020 in Potsdam, Germany. Organized in cooperation with the Denver Art Museum (Colorado USA), the paintings diplayed inside Potsdam’s Museum Barberini followed Monet’s journeys from the forests near Paris to the seaside in London and Venice, and along the coastlines of France. To further study color, reflections on the water, and the varied effects of weather conditions on nature, Monet also traveled to the Netherlands and Norway. The German word “orte” refers to the “places” where Claude Monet chose to paint and to live.

Normandy & the Forest of Fontainebleau

Although born in Paris, Monet grew up in Le Havre, a booming port city in the Normandy region of northern France that was the country’s second largest harbor at the time. After an early career as a caricaturist, he turned his attention to Normandy’s seacoast and lush countryside, accompanying established realist painters like Eugene Boudin, Johan Barthold Jongkind and, later, Charles-François Daubigny on painting excursions. These artists mentored the young Monet, encouraging him to paint outdoors — en plein air. The experience of direct contact with nature set Monet on the artistic path he would follow from then on.

Modern Life: Paris & Its Surroundings

For anyone wishing to become an artist in the second half of the 1800s, Paris was the place to be. The city bustled with energy and optimism, and opportunities to learn and exhibit one’s works were plentiful. The Impressionist movement, which rejected the rules of the Academy of Fine Arts about how and what to paint, started in Paris. Monet and like-minded artists began experimenting with loose brushwork and pure, unblended colors to capture the light and movement they observed directly in nature and in everyday life around the city. Short trips to the countryside for leisure activities also became easier, as a rapidly developing railway system now offered fast access to several flourishing resort towns.

Escaping to The Netherlands

After moving to London in 1870 to escape the Franco-Prussian War and the civil unrest that followed, Monet spent four months in Holland in 1871. This was the first of several trips to the Netherlands throughout his life. During his first visit he lived in the small town of Zaandam near Amsterdam. Zaandam’s network of crisscrossing canals, distinctive windmills, lively river life, and quaint, jumbled architecture offered a change in scenery that pleased and fascinated Monet.

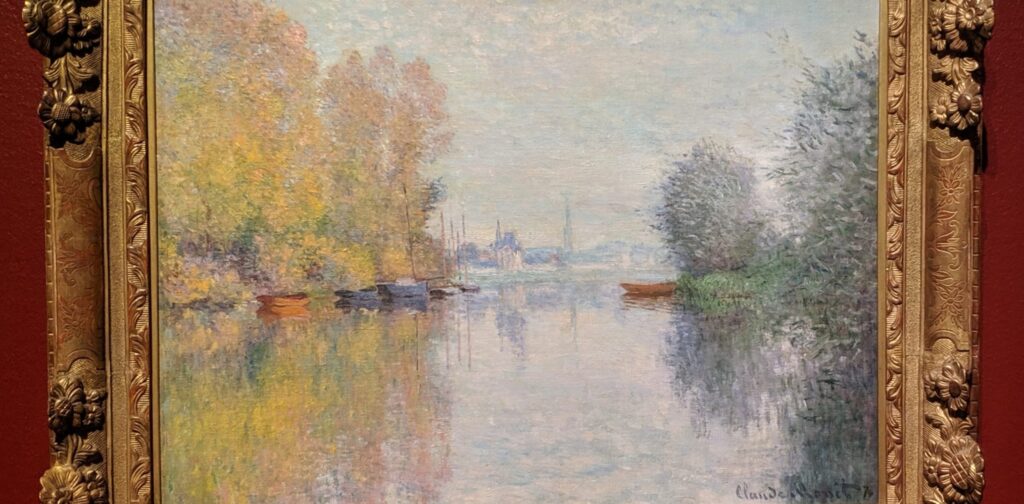

Settling in Argenteuil

In late 1871, Monet returned from the Netherlands and settled in Argenteuil, a fashionable escape for city dwellers only fifteen minutes by train from Paris. A haven for pleasure boating and weekend excursions, Argenteuil offered an appealing mix of modernity and pastoral serenity. Accompanied by his wife Camille and son Jean during his seven-year stay, he enjoyed domestic happiness and financial stability. His contentment is evident in these peaceful paintings. Argenteuil’s location by the Seine must have played a key role in his choice to settle here, as his subsequent moves to Vétheuil and Giverny followed the path of the Seine deeper into the French countryside.

Pure Landscapes — Vétheuil

In 1878 Monet moved to Vétheuil, leaving behind increasingly populated Argenteuil. Located on the banks of the river Seine about a three-hour train ride from Paris, Vétheuil was truly in the countryside — a sleepy, medieval village largely untouched by the industrialization that had changed the look of Argenteuil throughout the 1870s. Surrounded by this more isolated and rural environment, Monet chose to paint views that centered “on nature” rather than “on the people out in nature,” thus focusing on pure landscapes. His attention to seasonal changes introduced a sense of introspection and immersion in the natural world that would occupy him for the rest of his life.

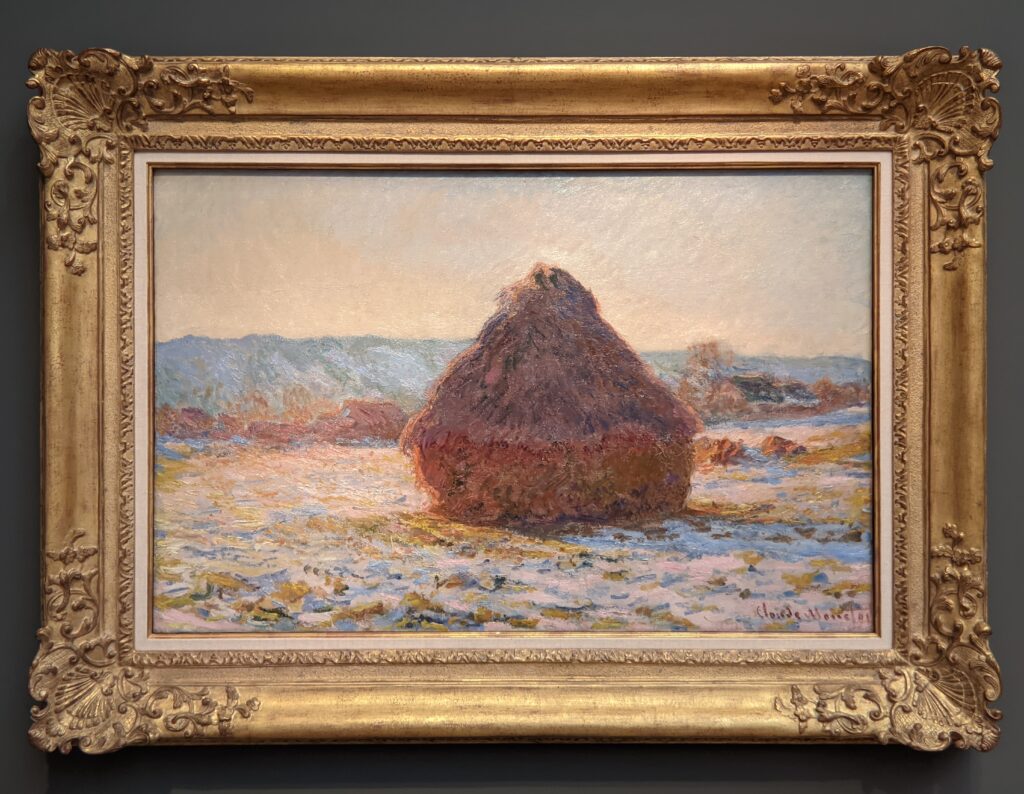

In Winter: France and Norway

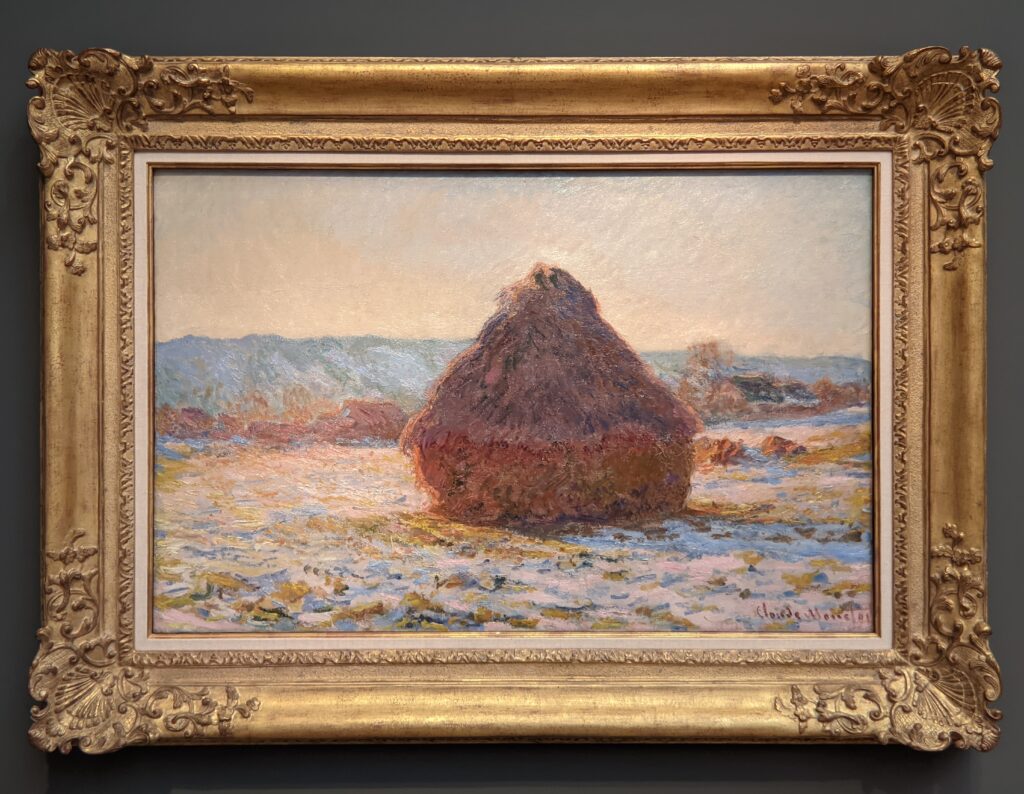

In the winter of 1879-80, it was so cold that the Seine froze. When it thawed, the blocks of ice flowing on the river offered a landscape unified by a palette dominated by white and fractured by fragments of frozen snow moving on the surface. Winter scenes from various locales recur in Monet’s work. Monet returned to the subject of an iced-over Seine during the harsh winter of 1892-93 while he was living in Giverny, and he traveled to Norway in 1895 to capture the snow-blanketed views of its countryside. With the subtle nuances of his color palette, Monet reminds us that white can indeed be the most complex of all colors.

Monet and Color

Monet caught the subtle nuances of color even within such a seemingly monochromatic scene as a snow-laden landscape. But he was often frustrated by color’s fleeting nature. Monet said, “I’m chasing the merest sliver of color…. I want to grasp the intangible…. Color, any color, lasts a second, sometimes three or four minutes at most. What to do, what to paint in three or four minutes? They’re gone, you have to stop. Ah, how painting makes me suffer!”

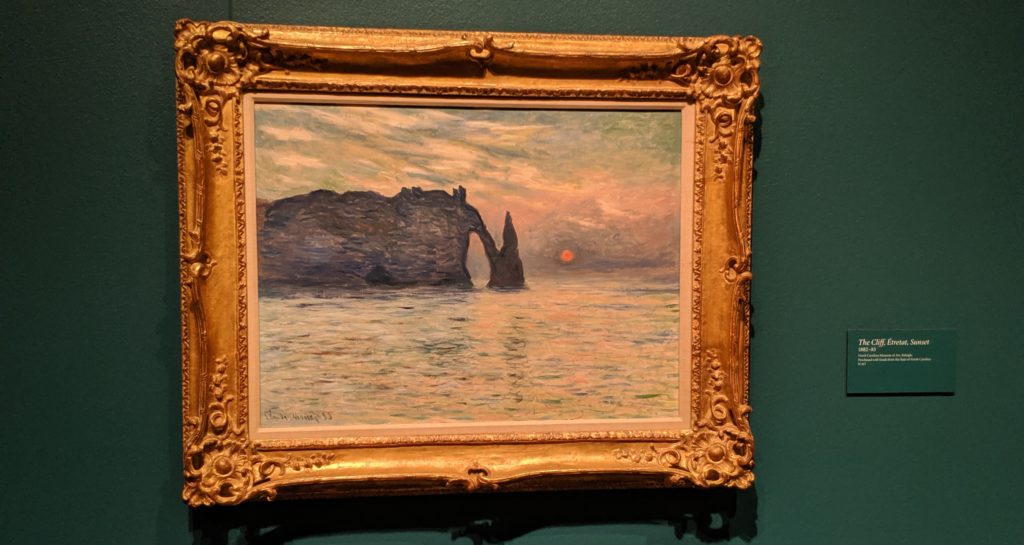

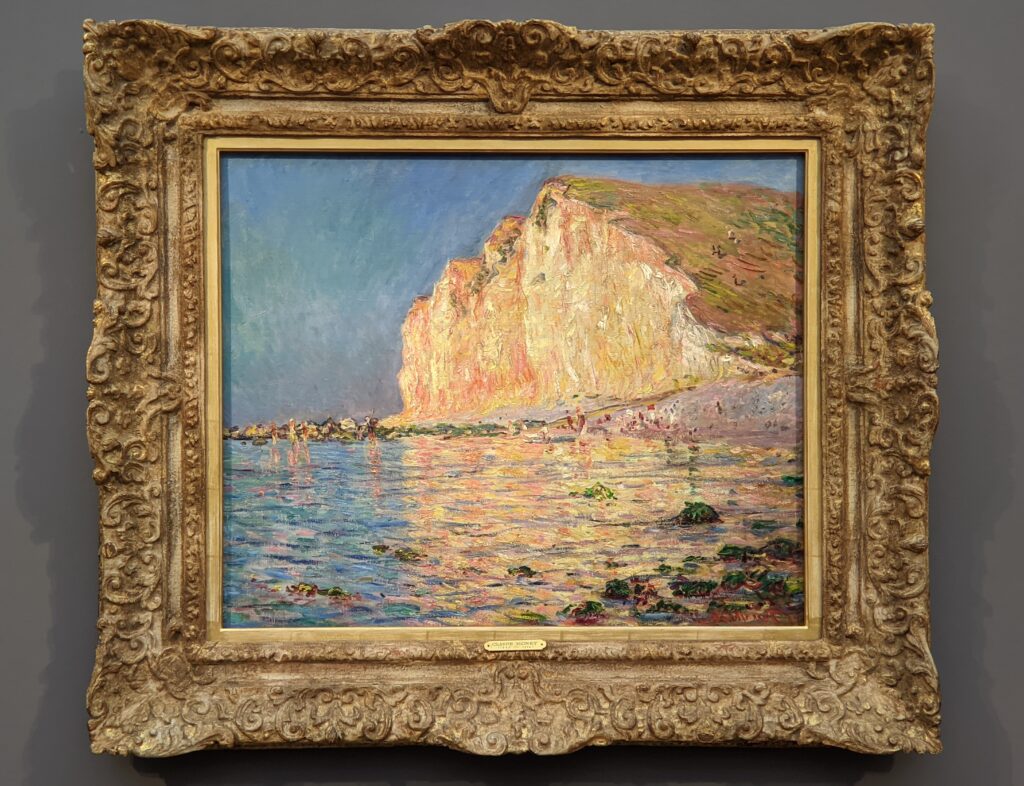

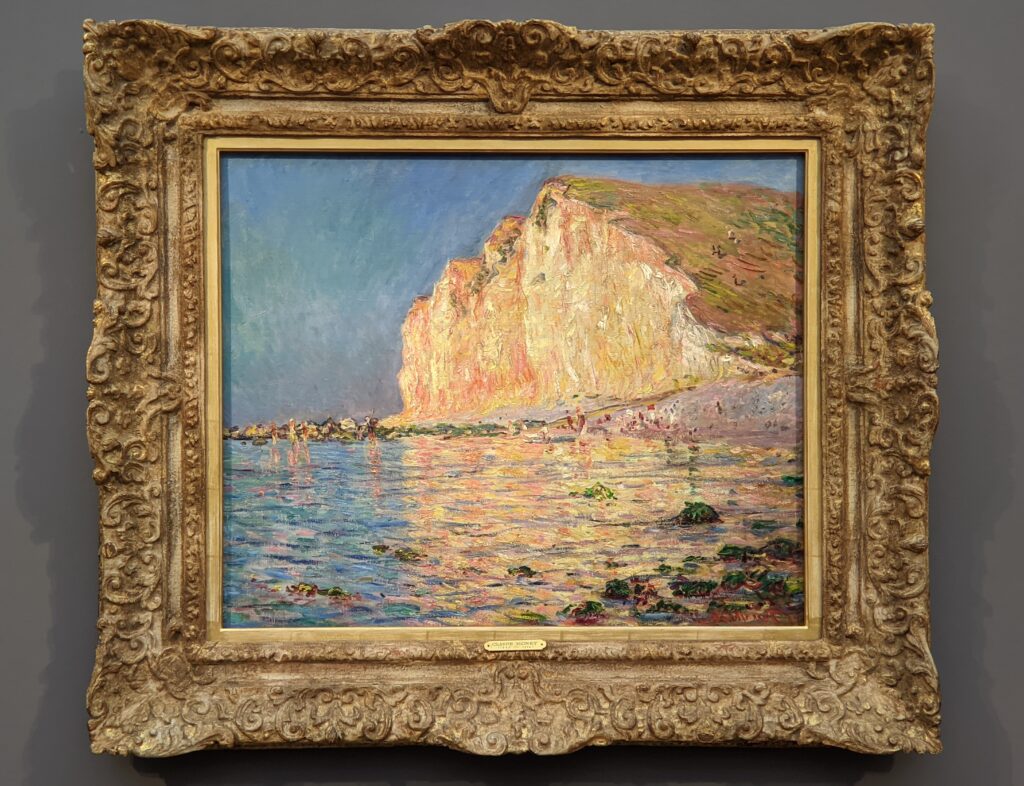

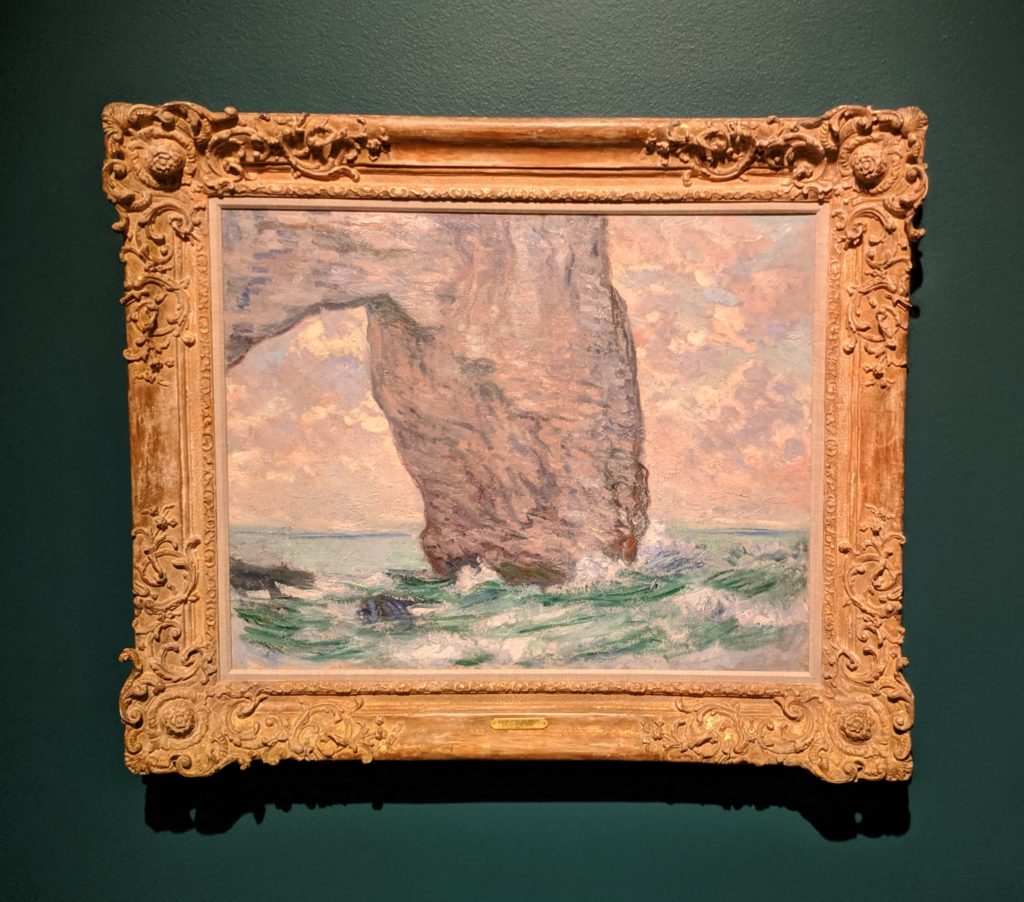

Rocks, Sea, and Sky — Northern Coasts

Monet was fascinated by the meeting of rocks, sea, and sky on the coasts of Normandy and Brittany in northern France and returned repeatedly throughout his life to paint their towns and villages. In his depictions of the windswept cliffs and white-capped water, Monet evoked a sense of nature’s power that was altogether different from the peaceful images he created of the Seine valley. By intentionally choosing a high vantage point, Monet maximized the dramatic encounter of natural elements.

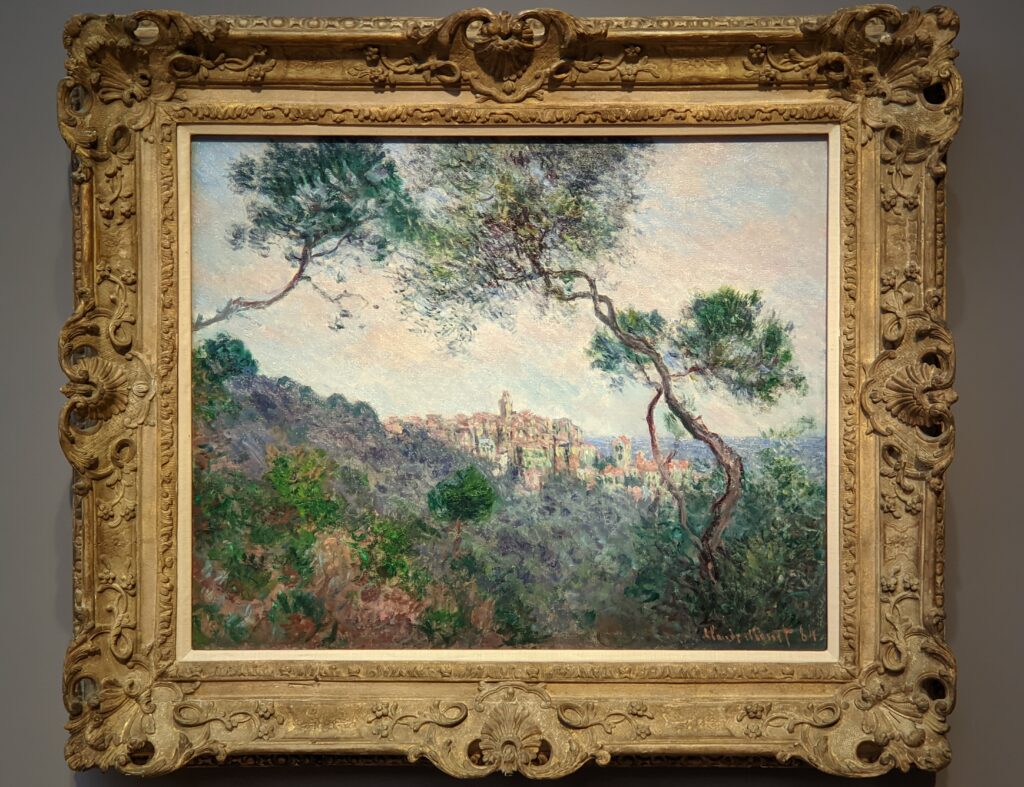

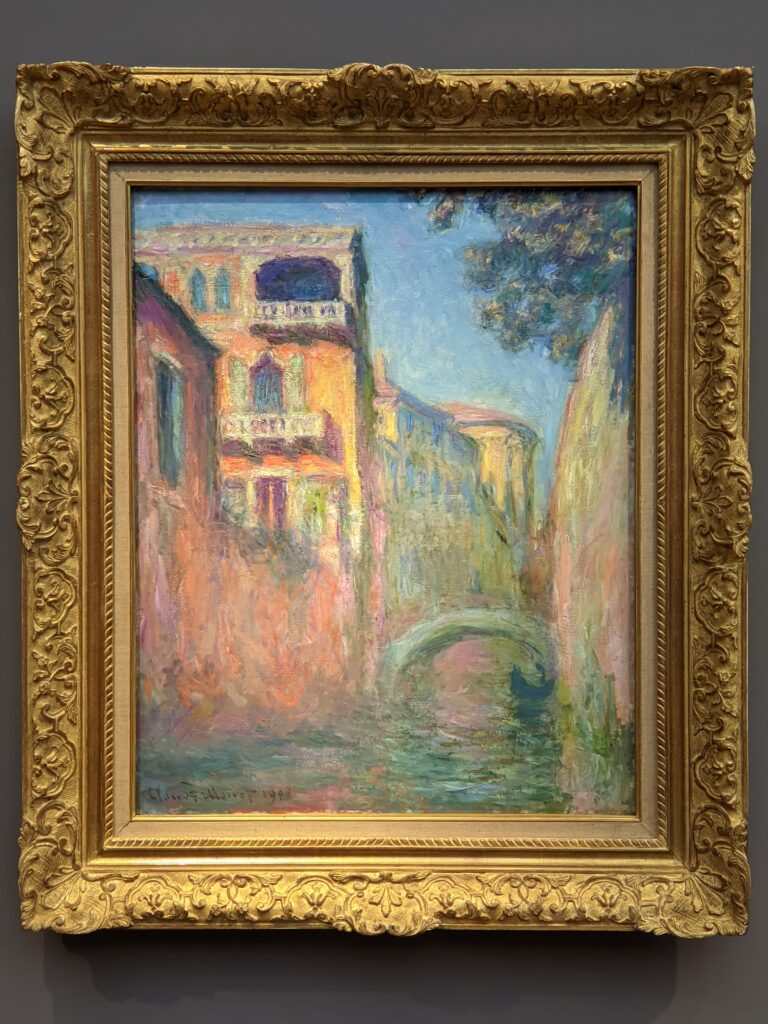

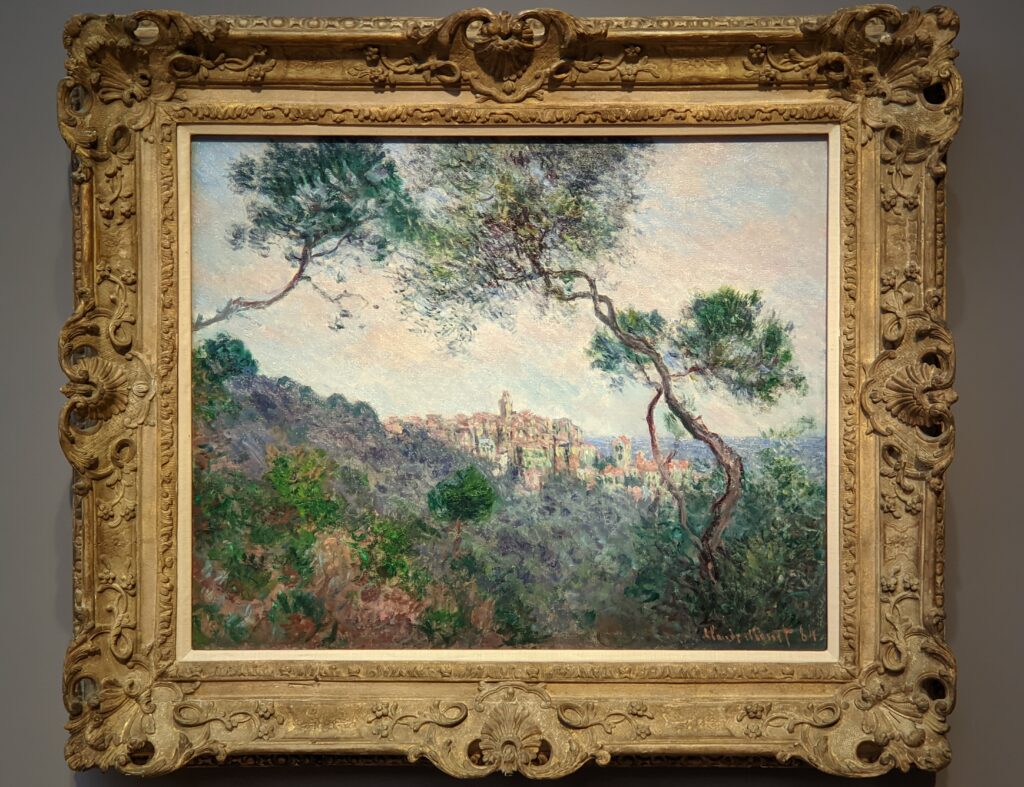

Southern Light: BORDIGHERA, ANTIBES, VENICE

Encountering the intense light and kaleidoscopic colors of the Italian and French Riviera in 1884 and 1888 was transformative for Monet. The enchanting light and exotic vegetation of the Mediterranean was unlike anything he had experienced before and inspired a number of bright landscape paintings. Monet felt he needed jewel-like colors to render accurately the buildings, palm trees, and azure water — “I’ve caught this magical landscape and it’s the enchantment of it that I’m so keen to render. Of course lots of people will protest that it’s quite unreal and that I’m out of my mind, but that’s just too bad,” Monet said. Likewise, when he visited Venice for the first time in 1908, Monet was again struck by the quality of light and the myriad reflections it offered.

The Colors of Fog: Le Havre to London

In the second half of the 1800s, London was the largest city in the world — a busy multicultural center of industry, banking, and trade. Monet traveled to London for the first time in 1870, and then made a string of visits around the turn of the century. Bridges, reflections of light, and shimmering veils of haze and mist over the river characterize Monet’s views of the English capital, often enveloped in a distinctive fog. He stated, “The fog in London assumes all sorts of colors; there are black, brown, yellow, green, purple fogs and the interest in painting is to get the objects as seen through all these fogs.”

Monet & the Seine at Giverny

The Seine, the long river that begins in the east of France, crosses through Paris, and ends in the English Channel, was a regular feature in Monet’s paintings throughout his career. For an artist enamored of water and attracted by the challenge of capturing its reflections, the Seine was an ideal choice. Monet’s search for direct contact with nature motivated him to follow the example of his friend and fellow painter Charles-François Daubigny and turn a boat into a floating studio, where, surrounded by water, he could paint his poetic and personal depictions of mornings on the Seine.

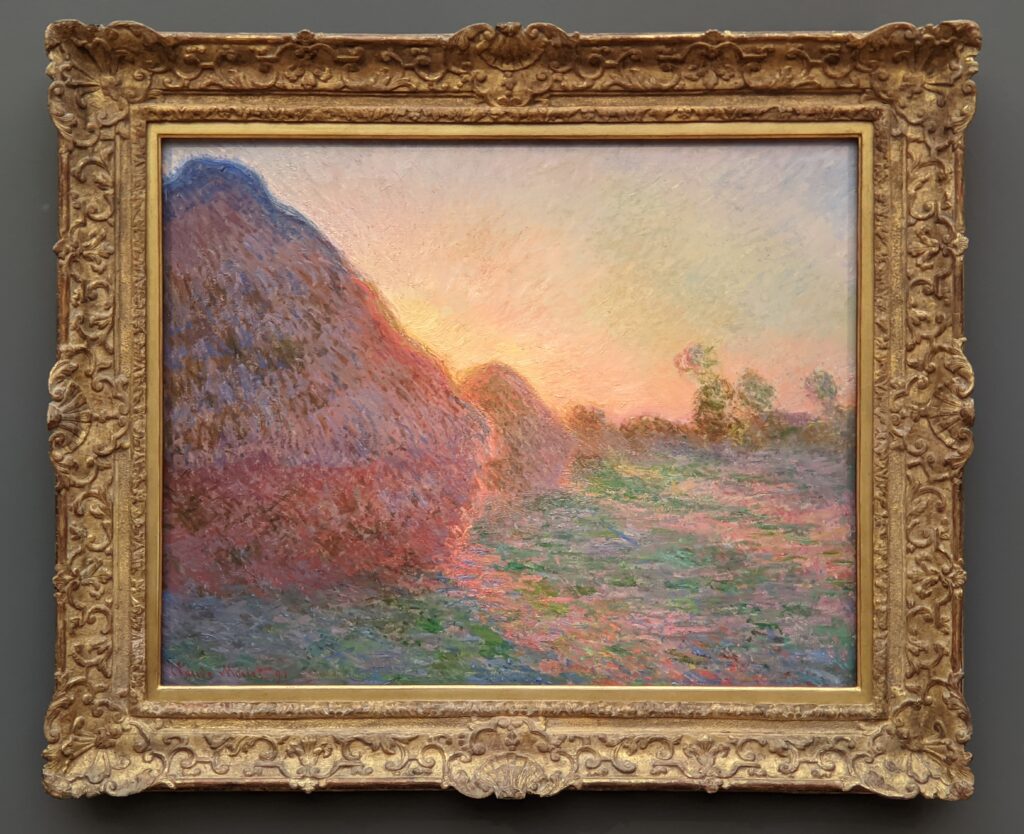

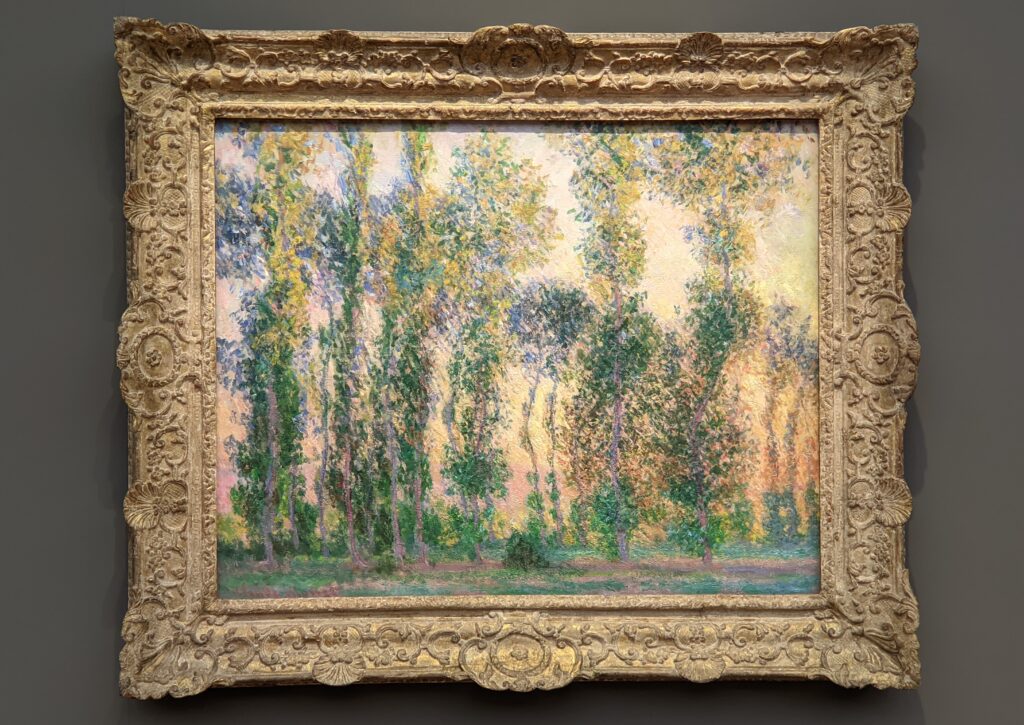

In 1883, Monet moved his family to Giverny, about ten miles further down the Seine from their previous residence in Vétheuil. Until his death in 1926, the small farming community remained his cherished home, which he recorded in countless landscape paintings. It was here that he designed his opulent gardens with the lavish waterlily pond that was to become the almost obsessive focus of his late work. But before that, his interests mainly lay in the agricultural and pastoral setting of Giverny, with its rows of towering poplar trees and fields of flowers, oats, and corn. He made multiple variations of grainstacks in the changing light of the seasons and times of day, resulting in his first comprehensive series devoted to one single motif.

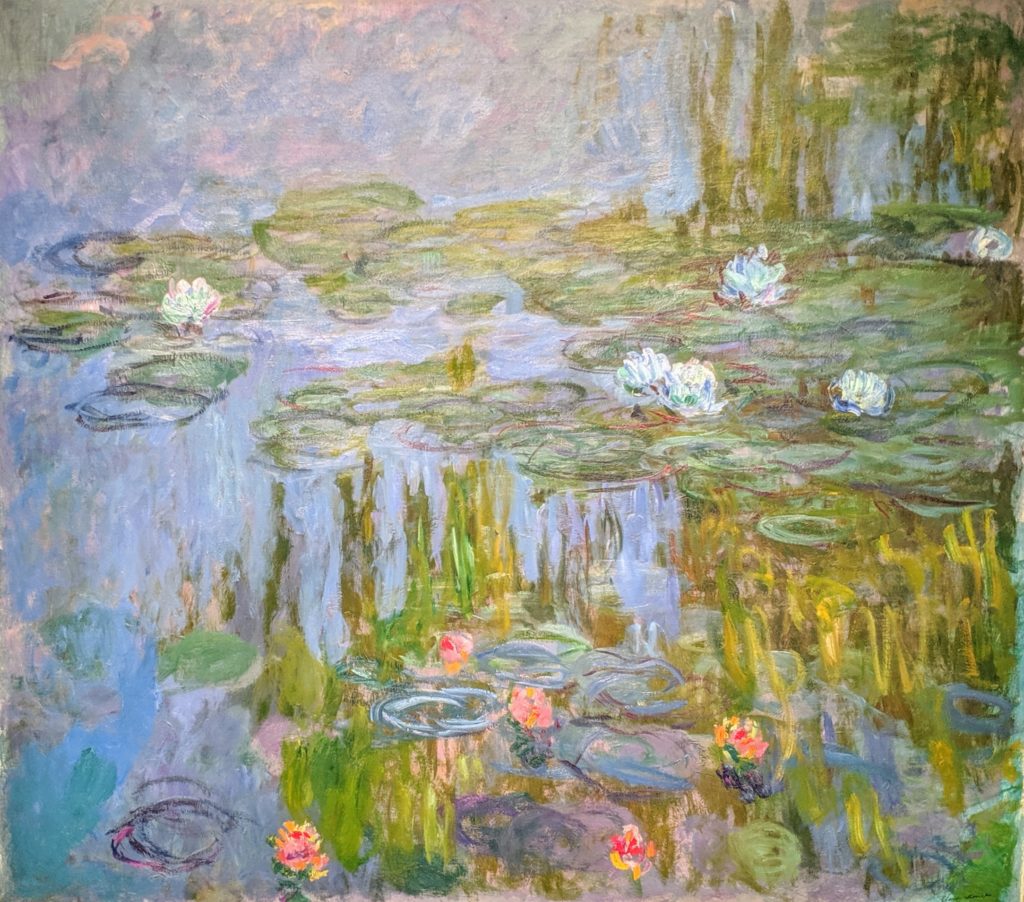

A Man-Made Paradise: Monet’s Water-Lily Pond

By purchasing an adjacent plot of land, diverting the flow of a nearby stream, and importing quantities of exotic plants, Monet created a magnificent water garden especially designed as a setting for plein-air painting. Modeled on Asian examples, it included a waterlily pond with a Japanese-style footbridge. The daily view of this man-made paradise and its constant changes with the hours of the day and the seasons inspired him to colorful depictions of nature, whose often radically free brushwork anticipated the abstract painting of the mid-20th Century.

All images of seascapes and landscapes shown above were taken by us in Potsdam, Germany and in Denver, Colorado, where this exhibition was shown in 2019-20 under the title Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature. Two photos taken from other sources are marked with an asterisk (*).

We owe special thanks to the Denver Art Museum for presenting the greatest display of Claude Monet paintings since the Art Institute of Chicago organized Monet: A Retrospective in 1995. We credit and thank the Denver Art Museum for some of the text which appears alongside our photographic images in this article.

The Largest Retrospective Devoted to Monet in a German Museum

We present this article for your pleasure, realizing that many of our readers and followers around the world were unable to view the exhibits “Monet: Places” — the largest retrospective ever devoted to Claude Monet by a museum in Germany — and “Impressionism in Russia” at the Museum Barberini.

The special exhibit at the Museum Barberini entitled “Surrealism & Magic: Enchanted Modernity” (which closed in 2023 in Germany) is reviewed herein in our article “The Best Surrealism in Venice and Potsdam“

“The Sun: Source of Light in Art” closed in Potsdam in 2023. If you wish to see some highlights from that exhibition, please read our article entitled “A Unique & Fabulous Pilgrimage to the Marmottan in Paris“

2025 Exhibition at the Barberini in Potsdam, Germany

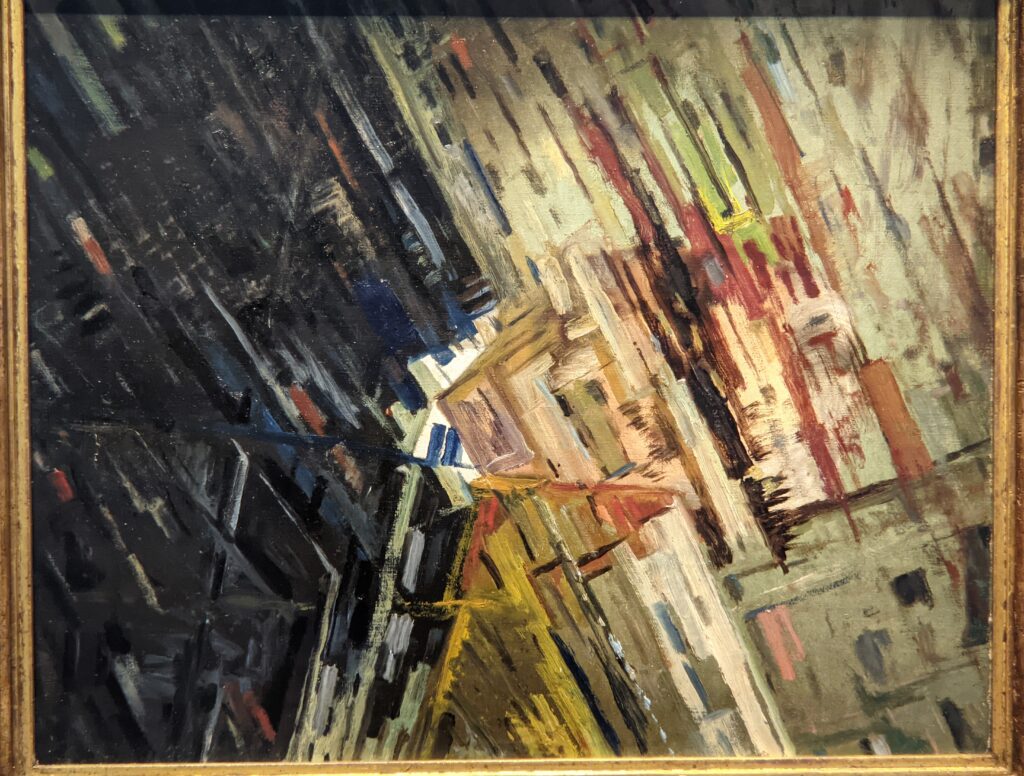

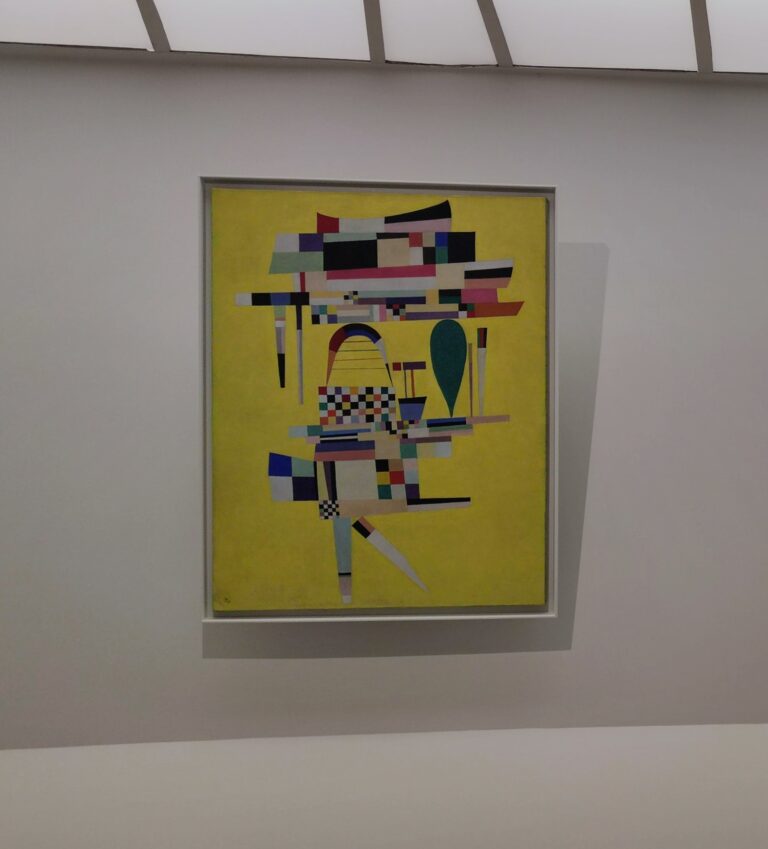

Kosmos Kandinsky — Geometric Abstraction in the 20th Century

February 15 – May 18, 2025

Painting underwent a profound transformation at the beginning of the 20th century. Artists no longer wanted to depict the visible; instead, they aspired to a new visual language that reduced artistic expression to an interplay of colors, lines, and shapes. The special exhibition Kandinsky’s Universe: Geometric Abstraction in the 20th Century at the Museum Barberini spans six decades and showcases how Geometric Abstraction found radical expression in all its variations in Europe and the USA.

Thank you for visiting. We encourage you to read our other articles, we appreciate your opinions, and we look forward to your comments regarding the greatest Impressionist Oscar-Claude Monet!