The Leopold Museum — 3rd Greatest Museum in Vienna

Vienna’s Leopold Museum is the best place to feel the dynamic power of modern Austrian art.

Housing around 6,000 works of art — including the world’s most comprehensive collection of the talented, enigmatic Egon Schiele — the Leopold Museum takes you on a journey from the 1860s to the Wiener Secession, through the stylish era of Jugendstil, and into Expressionism.

Like Tina Turner’s version of Proud Mary, a visit to the Leopold starts you off “nice and easy” … then undulates you across a kaleidoscopic wave of creative movements … and leaves you feeling “nice and rough.”

Portrait of a Changing Europe at the Leopold Museum

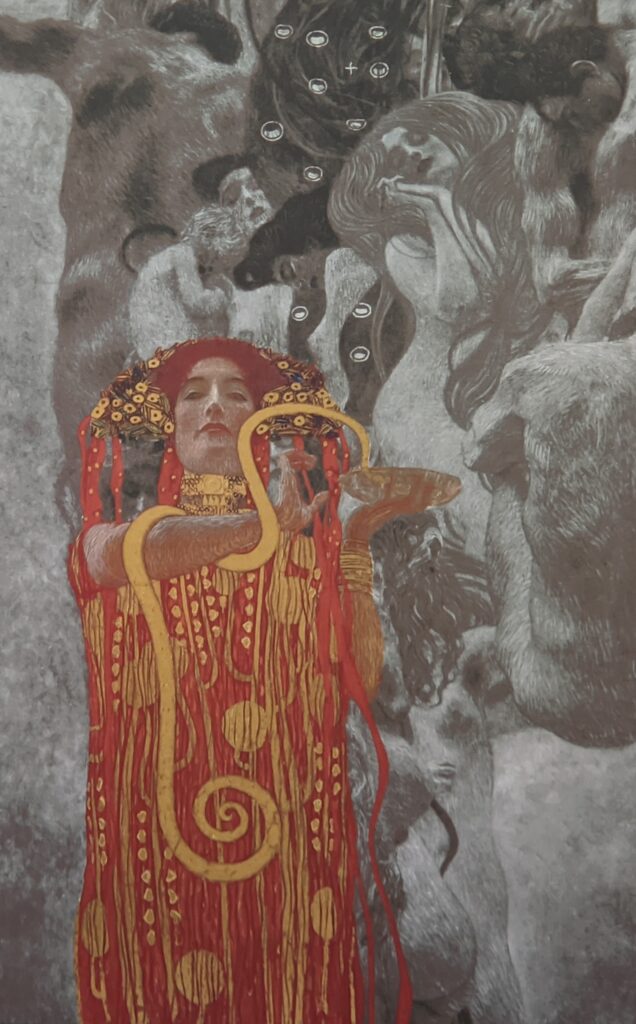

In mid-19th century Europe, would-be artists born in Austria and other centers of culture were trained under the strict influence of academies of art, where the subject matter they painted was simplified and idealized. Classical, mythological, historical and religious themes were encouraged and prized; whereas contemporary advances, trends and social concerns were ignored. In Vienna, Robert Russ depicted landscapes in a pure, classical style and Hans Makart began incorporating decoration into his canvases as he veered away from Academic art and toward Symbolism.

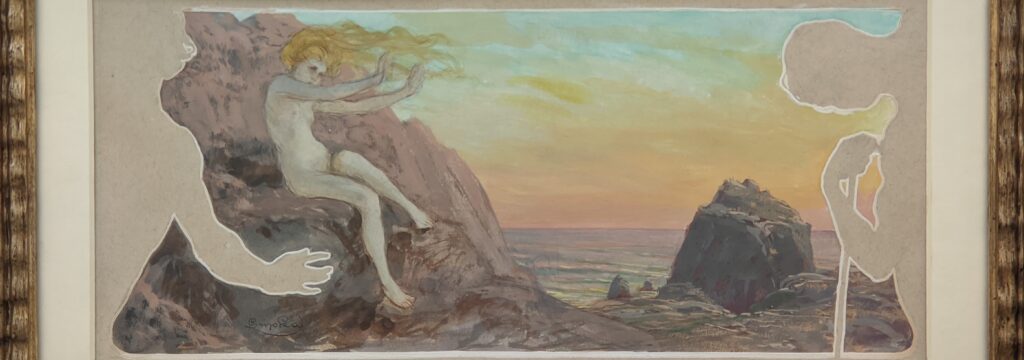

Paintings from the 19th century at the Leopold Museum include “Seated Young Girl,” 1894 (above left) by Gustav Klimt, “Dance of the Elves” from 1899 (above right) by Josef Maria Auchentaller and “Landscape with Waterfall,” 1866 (below) by Gustave Courbet. Auchentaller (1865 — 1949), an architect, created paintings in the style of Art Nouveau and Japonisme, popular movements during that time.

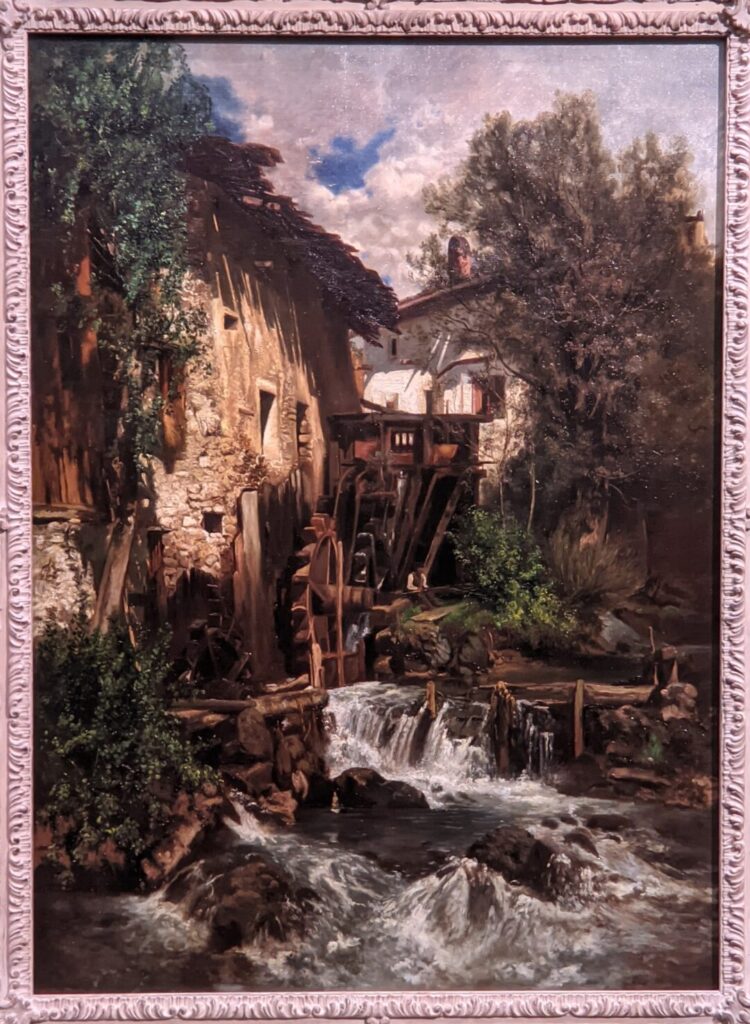

The major population centers in Continental Europe between 1850 and 1900 were Paris, Vienna, Berlin and Saint Petersburg. The French painter Gustave Courbet (1819 — 1877) rejected the Academic art and Romanticism of the previous generation of visual artists and became the leader of the Realism movement.

Courbet committed himself to painting only what he could see. By championing realistic depictions of ordinary life and immediacy, he paved the way to Impressionism and beyond. In the Leopold’s splendid “Landscape with Waterfall” (above) we see that Courbet used a spatula and palette knife to color treetops, rocks and the waterfall. This represented a considerable departure from Academic art, where all surfaces appeared smooth and slick.

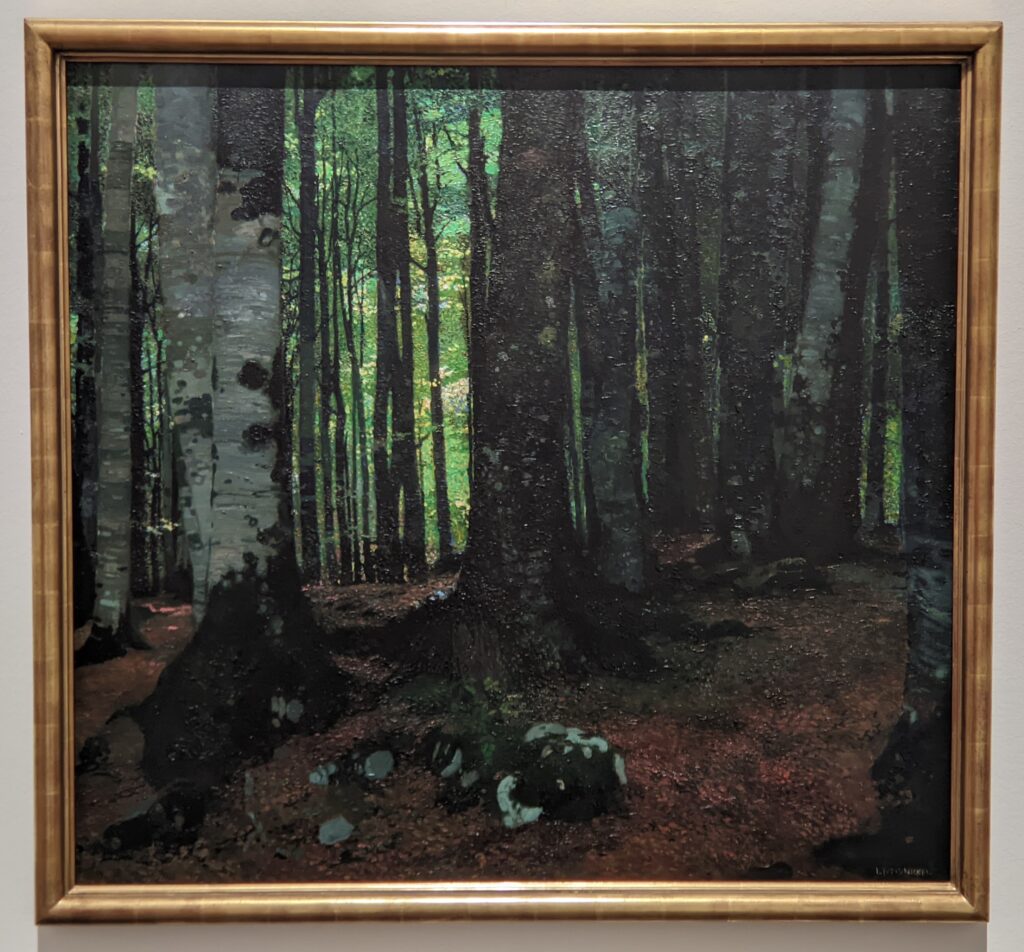

Carl Moll

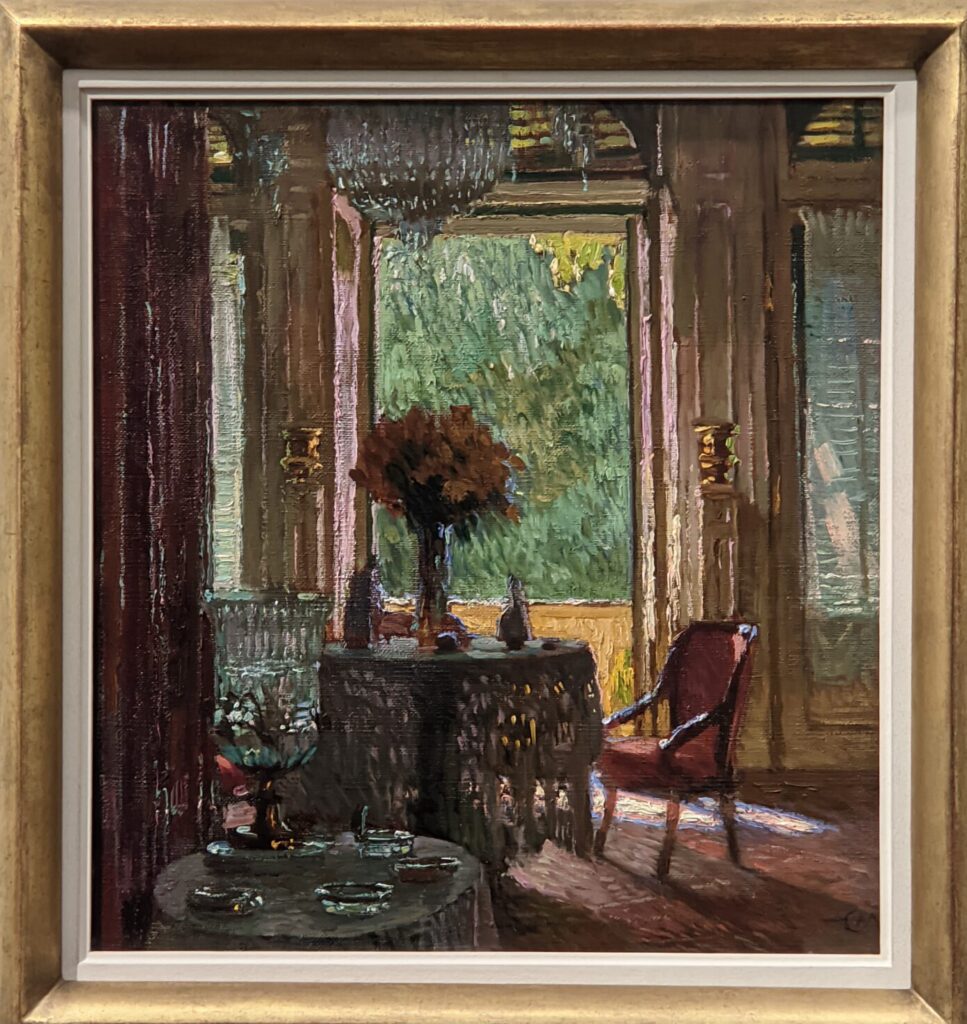

Adopting inspiration and techniques from Courbet and the French Impressionists, Carl Moll (1861 — 1945) became one of the most prominent Jugendstil {Art Nouveau} painters in Vienna at the start of the 20th century.

You will notice that the surface of Moll’s impressive canvases are textured.

Sophistication, Diversity & Cultural Blossoming in fin-de-siècle Vienna

In many ways, Vienna between 1890 and 1918 resembled modern Western cities of today. As the principal metropolis of the Austro-Hungarian empire and the center of its government and commerce, Vienna became one of the first multi-ethnic, modern cities. The elegant Ringstrasse in the center of Vienna was simultaneously the seat of rigid Conservatism, the aristocracy and liberal Intellectualism — surrounded by huge slums.

Situated at the nexus of Eastern European and Western European cultures, Vienna in 1900 was a magnet for migrants from present-day Poland, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Lithuania, and home to diverse ethnolinguistic groups of Hungarians, Slavs, Austro-Germans and others present in the vast Habsburg empire. This amazing diversity gave rise in Austria to modern architecture & art, the twelve-tone technique in music, psychoanalysis and major schools of thought in the realms of philosophy, law and economics. However, this cultural blossoming took place as the political power of the empire was waning and internal stability was jeopardized by rising ethnic conflicts, anti-Semitism and political tensions.

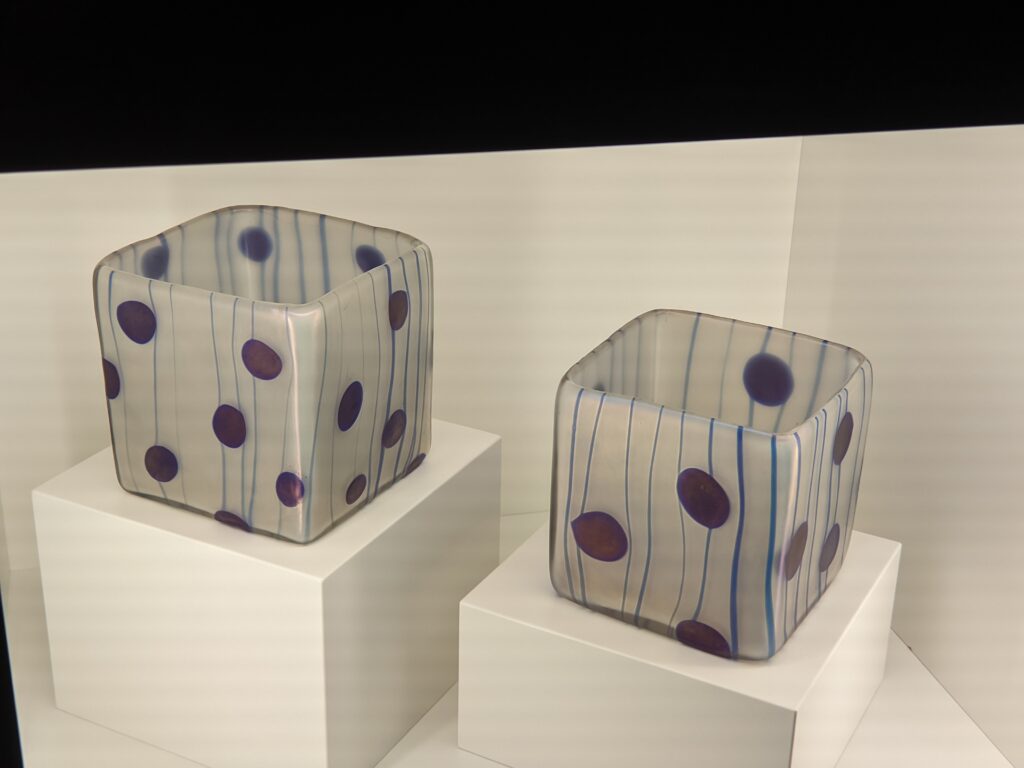

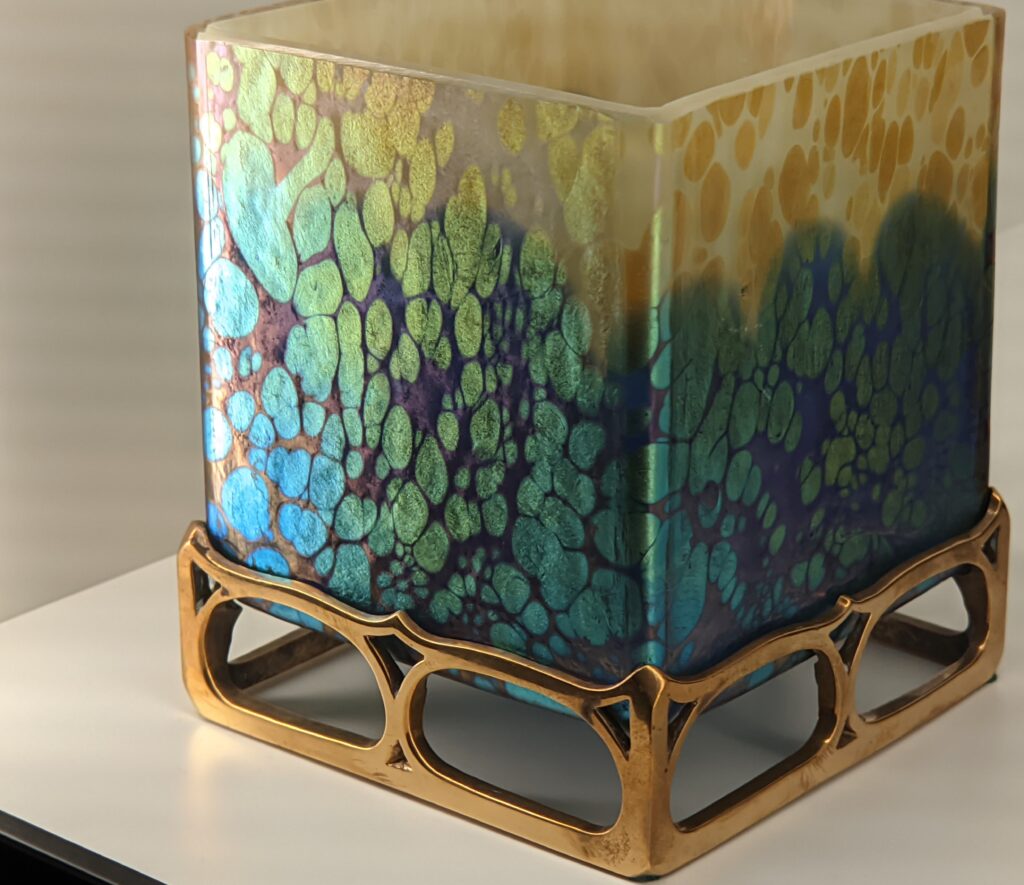

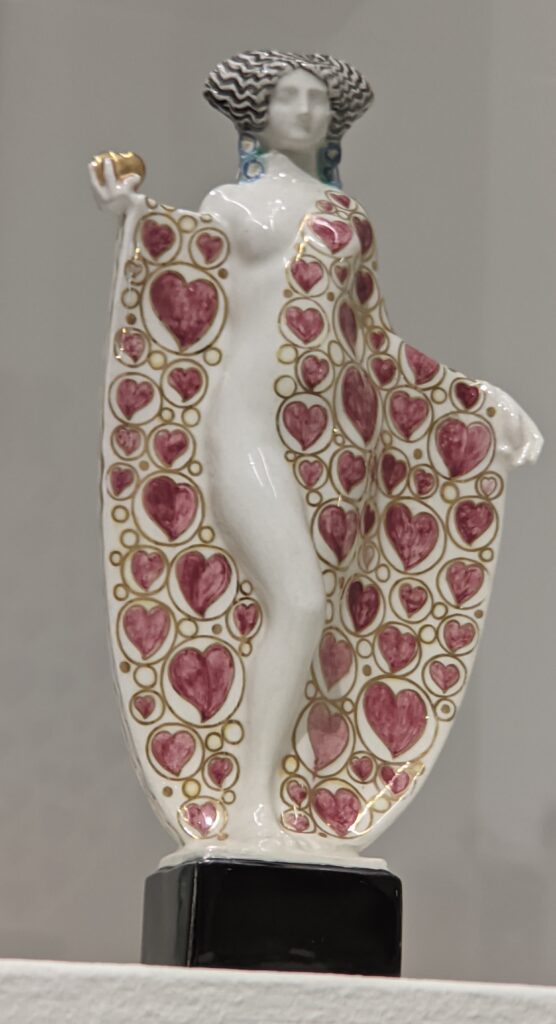

The Secession Elevated the Applied Arts to the Same Status as Painting

With the founding of the Vienna Secession in 1897, the goals and vision of Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser were made clear: to infuse art into every facet of human life, to initiate an exchange of ideas with artists outside of Austria, and to create a “total art” that unified all of the visual and creative arts. Thus, for the first time, applied and decorative arts were elevated to a new level equal to that of architecture and painting. Over time, a concept for the production of modern decorative art was developed, leading to the establishment in 1903 of the Wiener Werkstätte.

We have described the Leopold as one of the greatest museums in Vienna today because the curatorial staff does an excellent job of integrating the glassware, fabrics, jewelry, photographs, leather goods, ceramics, furniture, metalwork, antiques, graphic art and decorative objects from the permanent collection (and loans from private collections) with the most comprehensive and important assemblage of modern Austrian paintings acquired over five decades by Elisabeth and Rudolf Leopold. The Leopold Museum opened in 2001.

Josef Hoffmann

Well-known internationally as an architect and designer, Josef Hoffmann (1870 — 1956) was one of the founders of the Vienna Secession, and he co-founded the Wiener Werkstätte with Koloman Moser.

In the Hohe Warte district in Vienna, Hoffmann built a duplex house on a hill overlooking the city for the families of Carl Moll and Koloman Moser.

Koloman Moser

Koloman Moser (1868 — 1918) was an influential figure in the development of twentieth-century graphic art, furniture design, fabrics and painting. He reacted to the Baroque decadence of turn-of-the-century Vienna by drawing inspiration from the classical lines found in ancient art and architecture from Greece and Rome.

In addition to being a first-rate painter, Moser was perhaps the most multitalented artist of his era, designing books, porcelains, stained-glass, jewelry, furniture, fashion, ceramics, tableware, and Austria’s leading art journal Ver Sacrum.

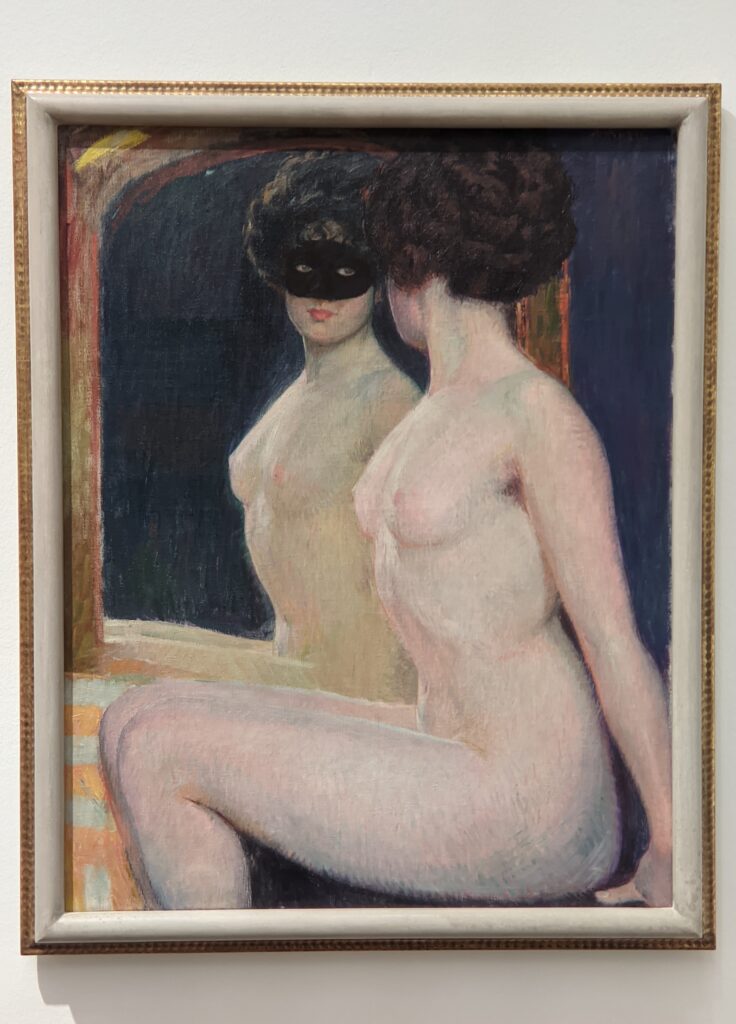

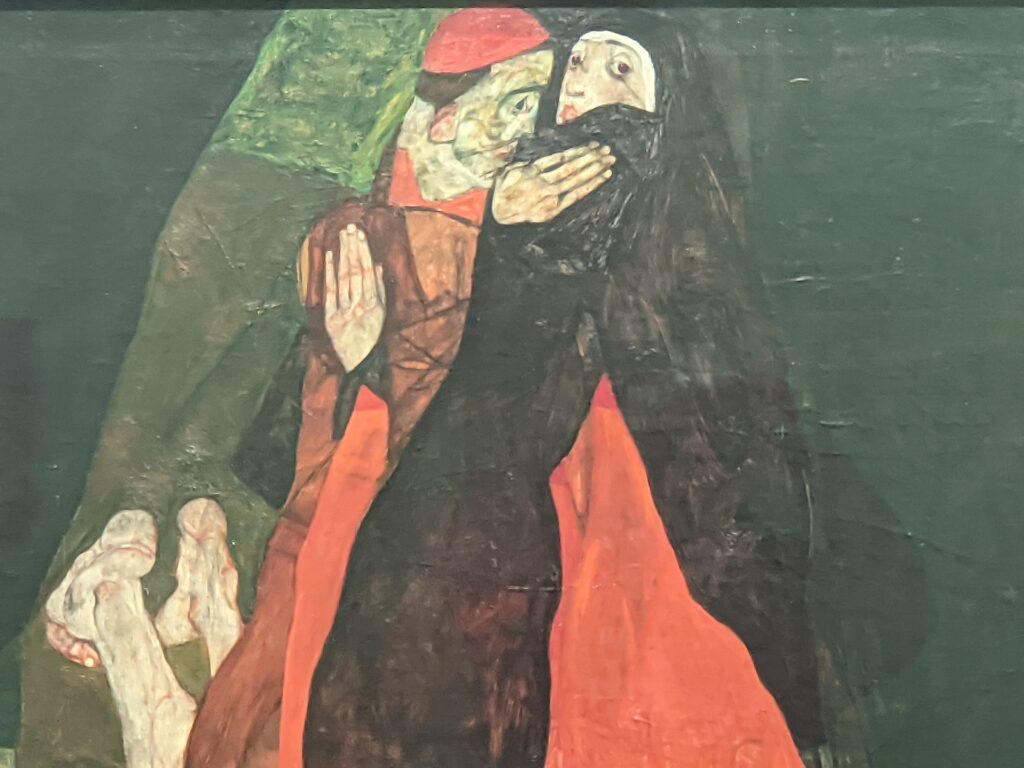

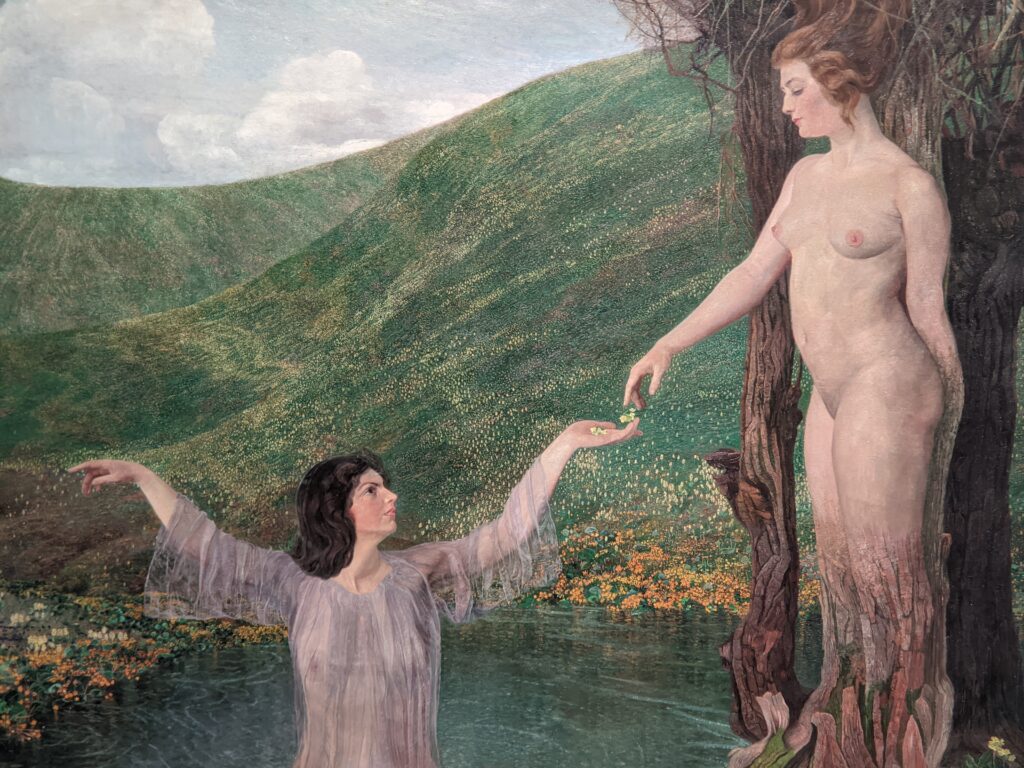

Exploring Human Complexity in a More Secular Society

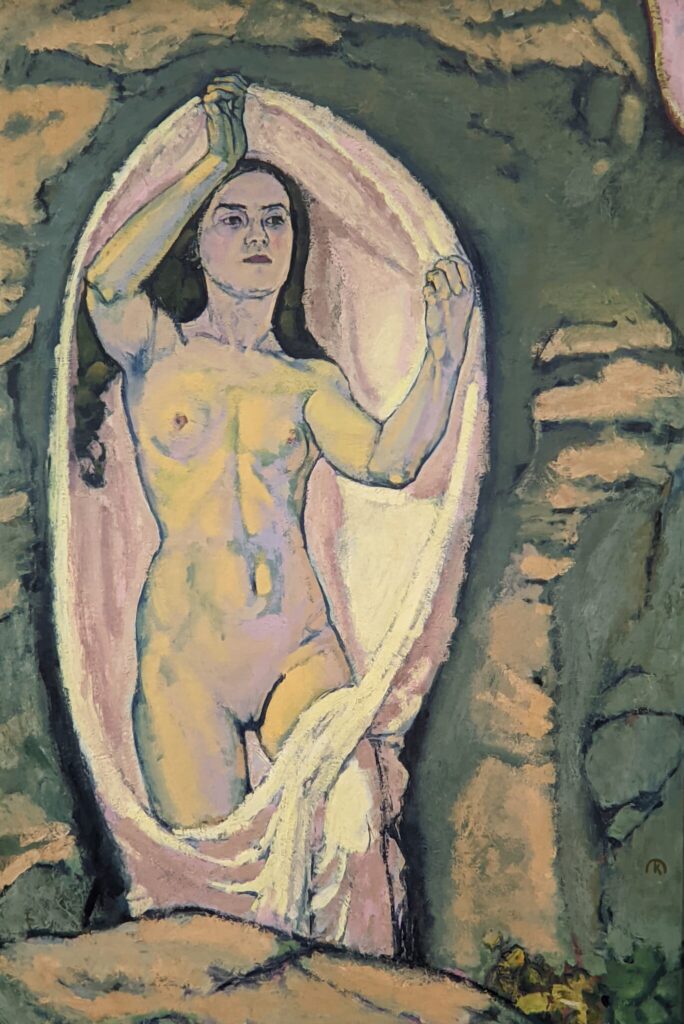

The Vienna Secession contributed to a growth in Liberalism — which moderated religious dictates and led to a reexamination of human sexuality — allowing Viennese artists to engender paintings with erotic themes like never before in the history of art.

This frank and unabashed exploration of the power of sexuality by Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele and the Secessionists also informed the tenets of Sigmund Freud, whose theories on human behavior (motivated by instinctual drives, including libido and sex) created a revolution in thought regarding the nature of the human psyche. Freud was born in the Habsburg empire; he lived and worked in Vienna.

By 1900, Vienna rivaled Paris to become an intellectual and cultural center of the Western World, bursting with energy, challenging traditional norms, embracing new fashions and ideas.

After becoming a member of the Vienna Secession in 1899, Emil Orlik broke new ground for the Secessionists by leaving his native Prague in 1900 (at the age of 29) and traveling to Kyoto and Tokyo. His interest in learning the technical aspects of creating ukiyo-e {Japanese woodblock color prints} later served as the basis for the paintings and printed graphics Orlik created when he moved his studio to Vienna in 1904. “Capriccio with Gilded Fan” (above), to quote the words of the Leopold’s curators, “combines Japanese and Secessionist elements in a sublime way by uniting the flatness of the stylized floral ornament with the off-center, foreground figure in a square picture format.”

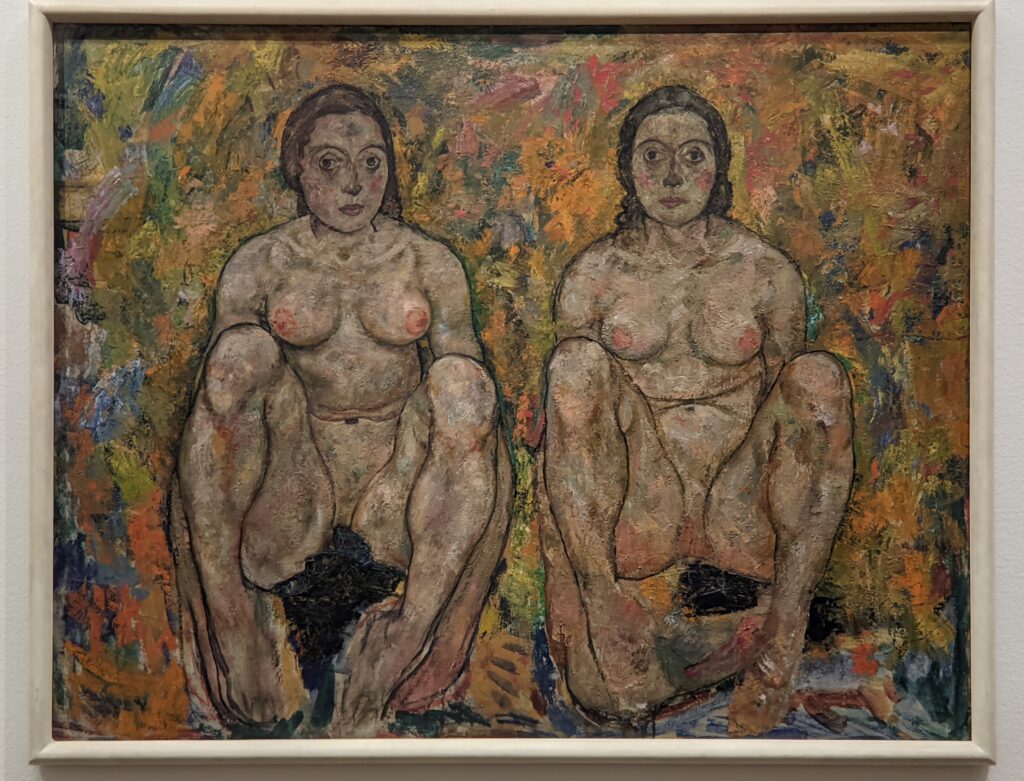

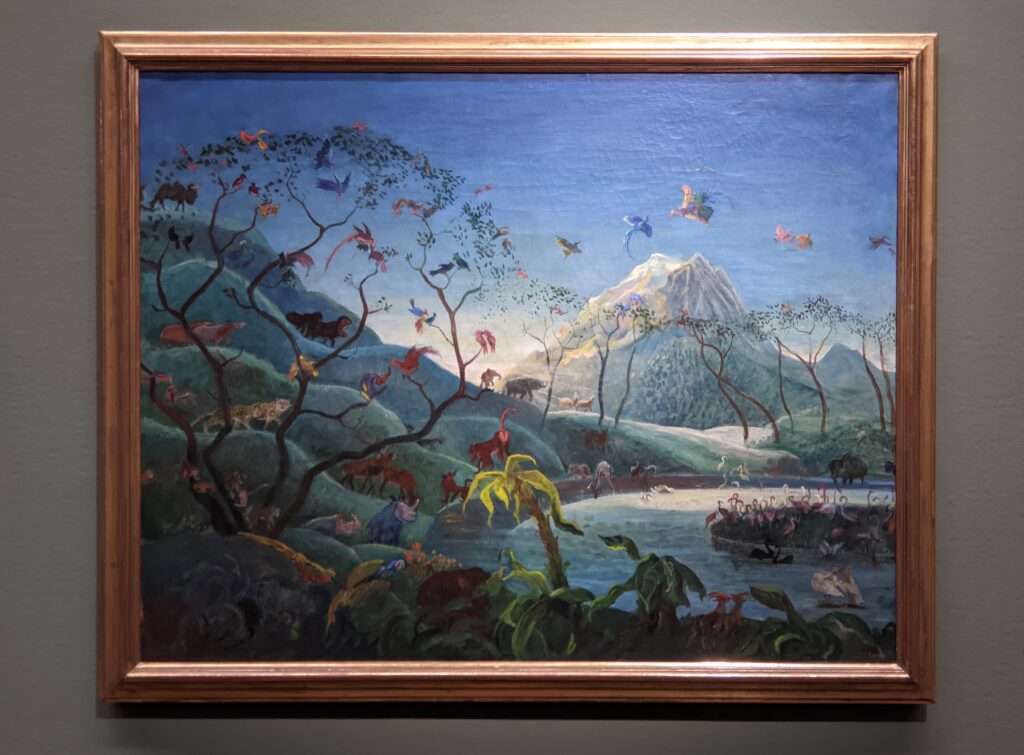

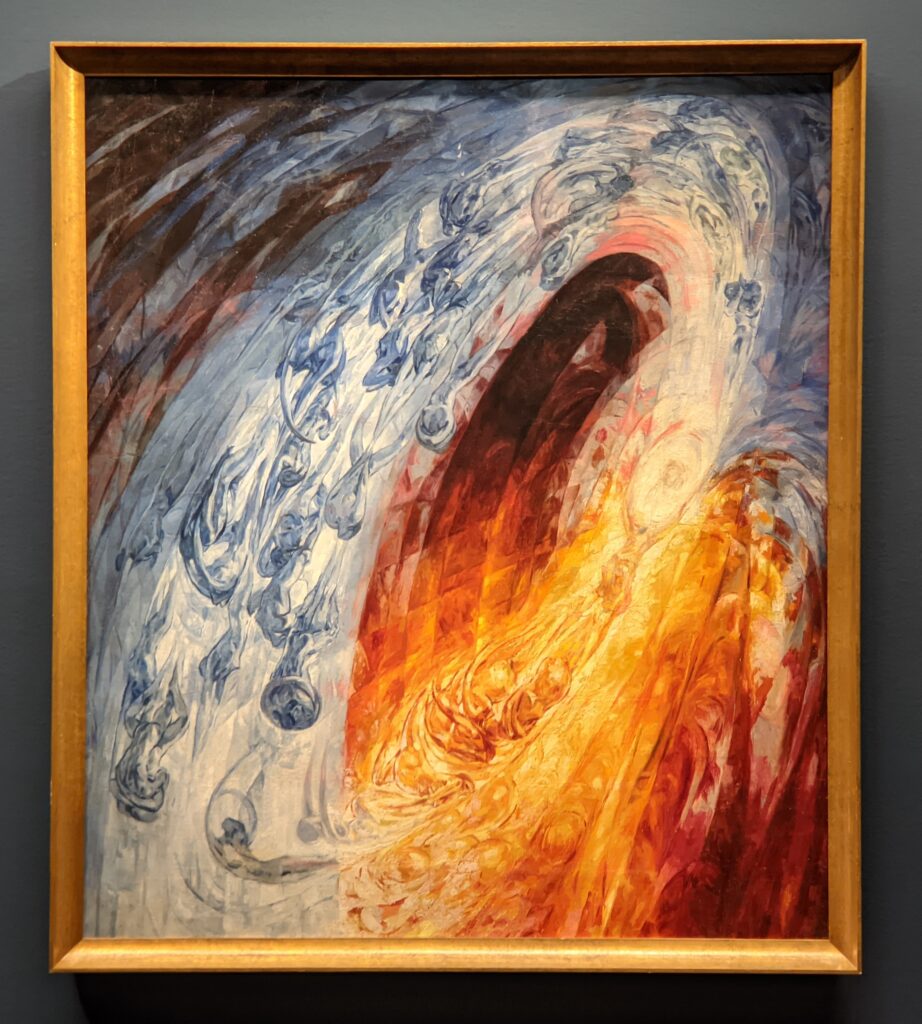

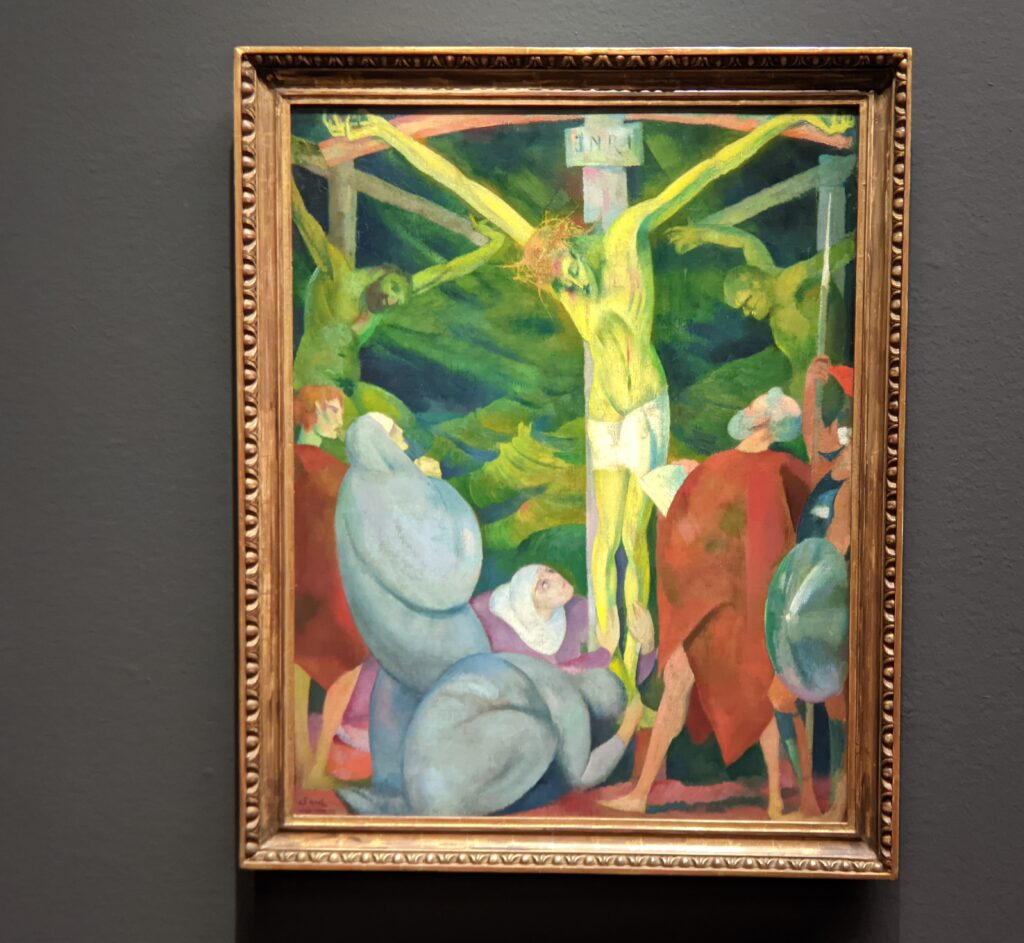

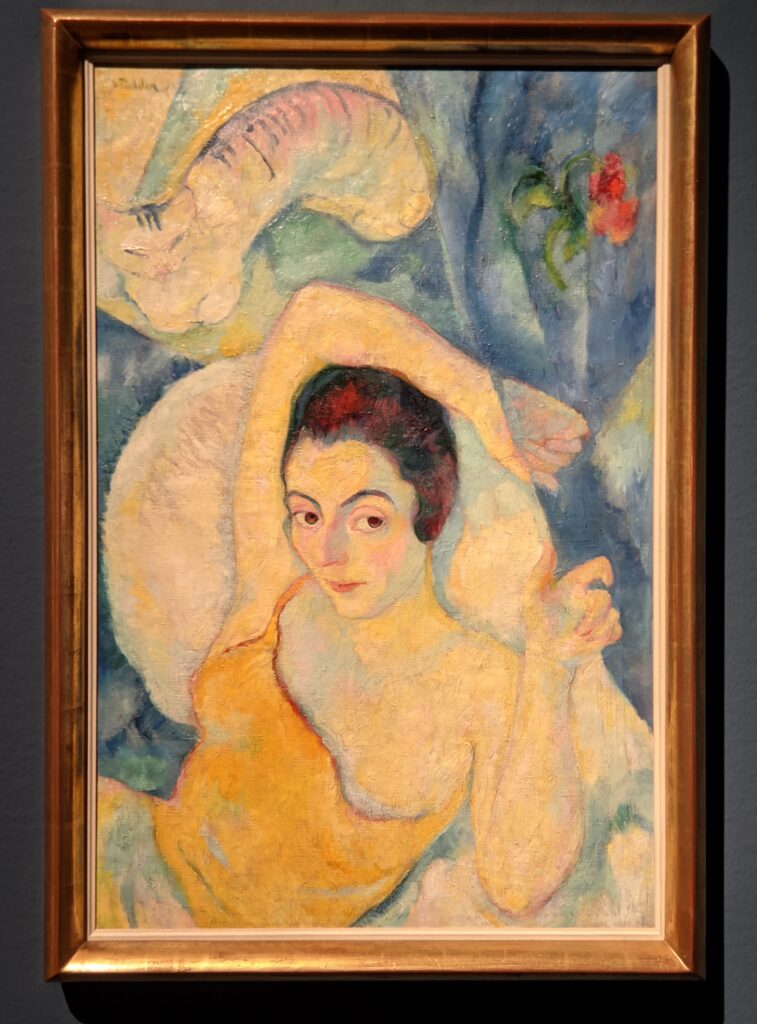

Paintings by Blau, Kolig, Kokoschka, Gerstl & List at the Leopold Museum

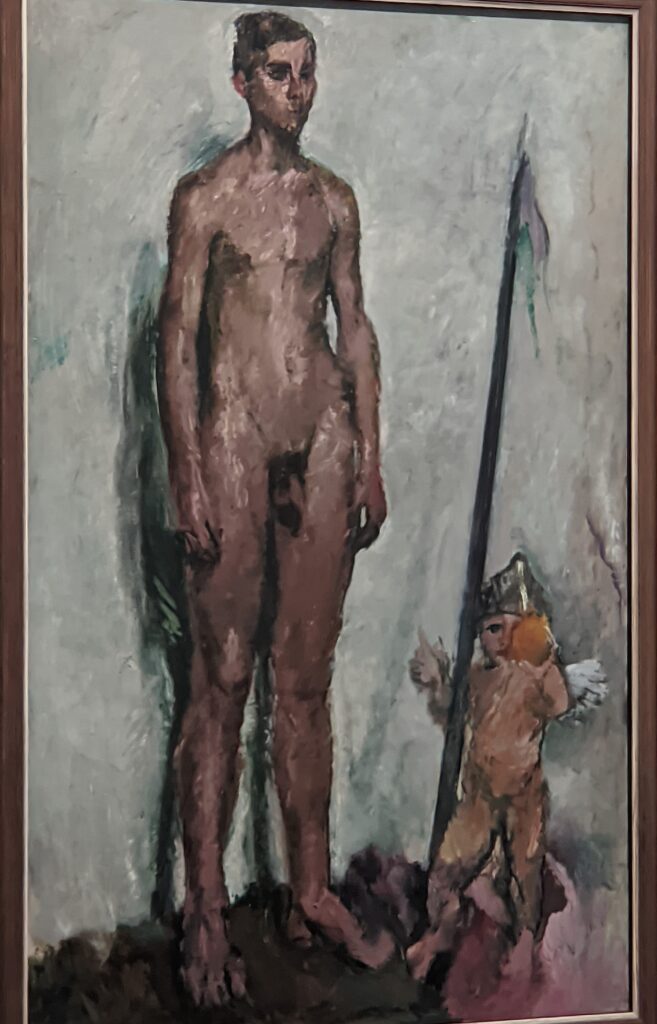

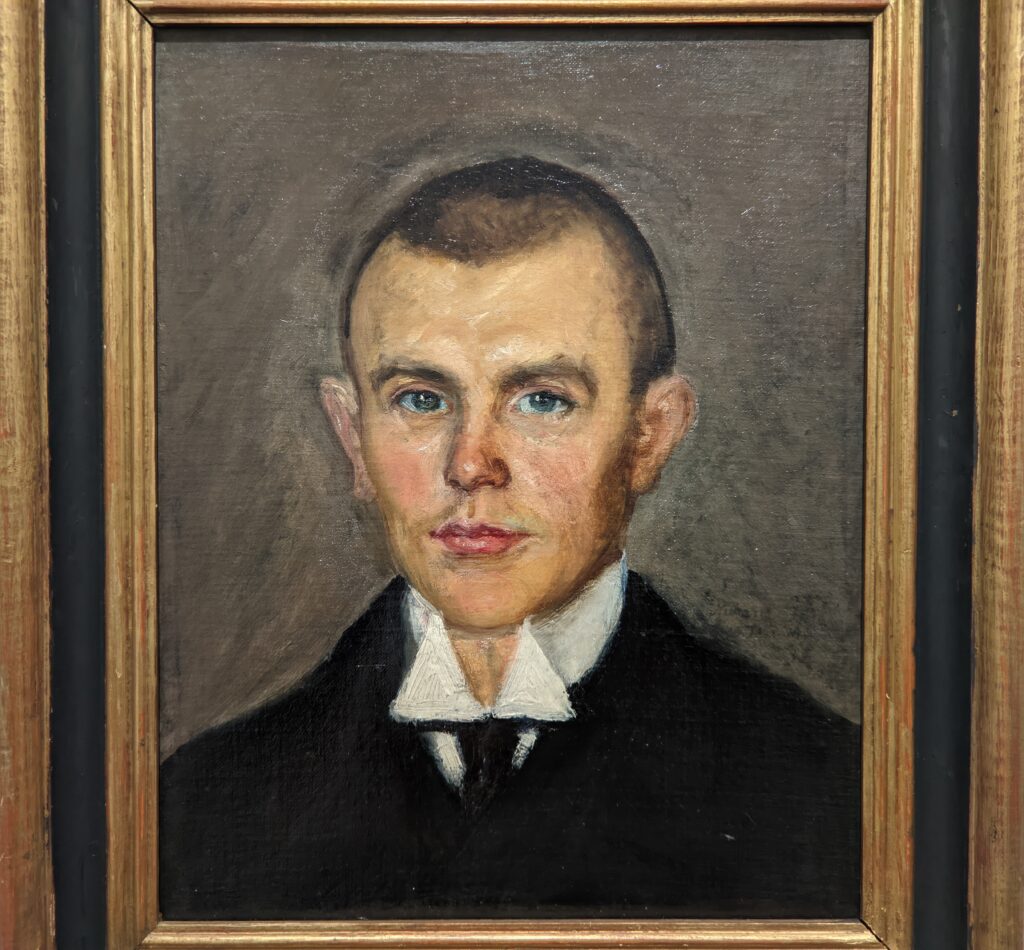

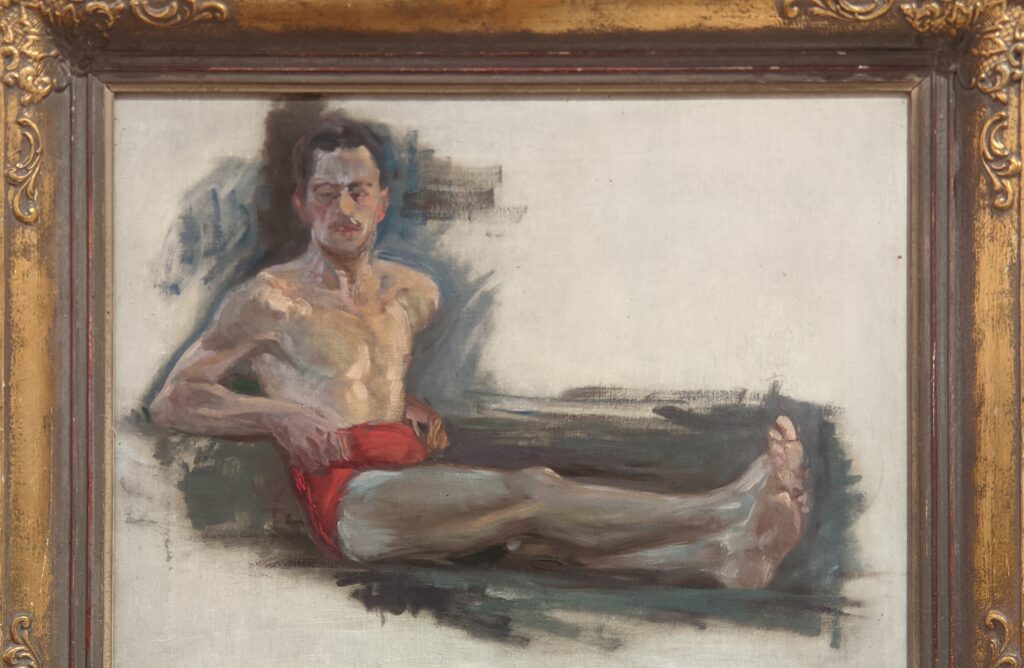

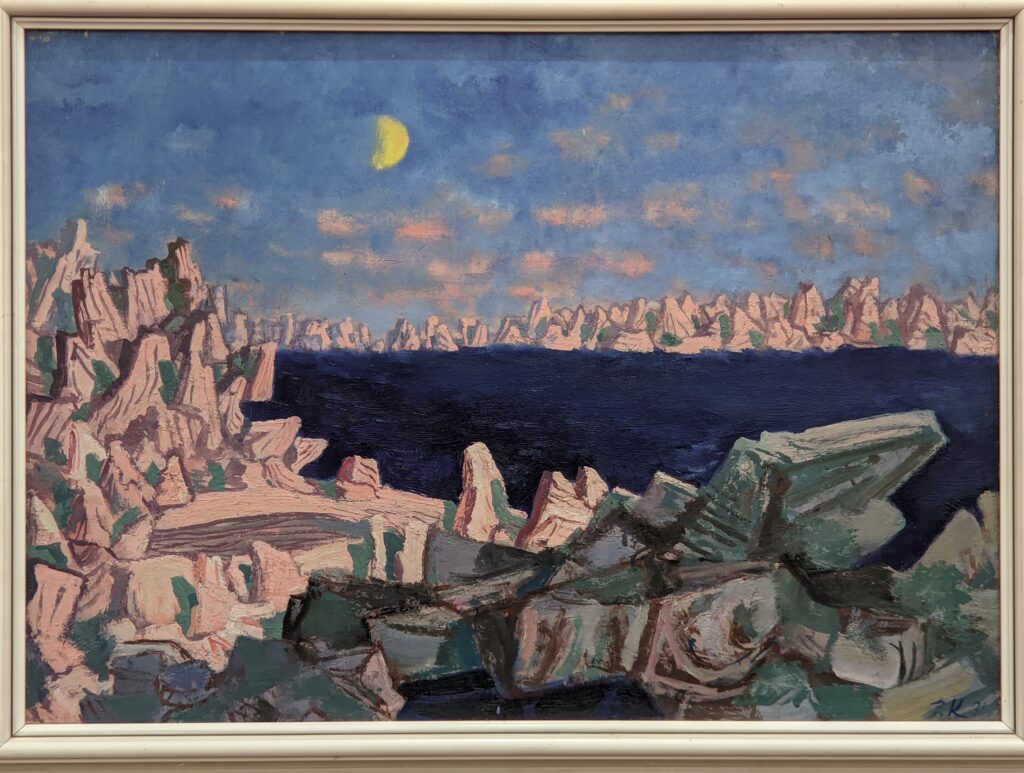

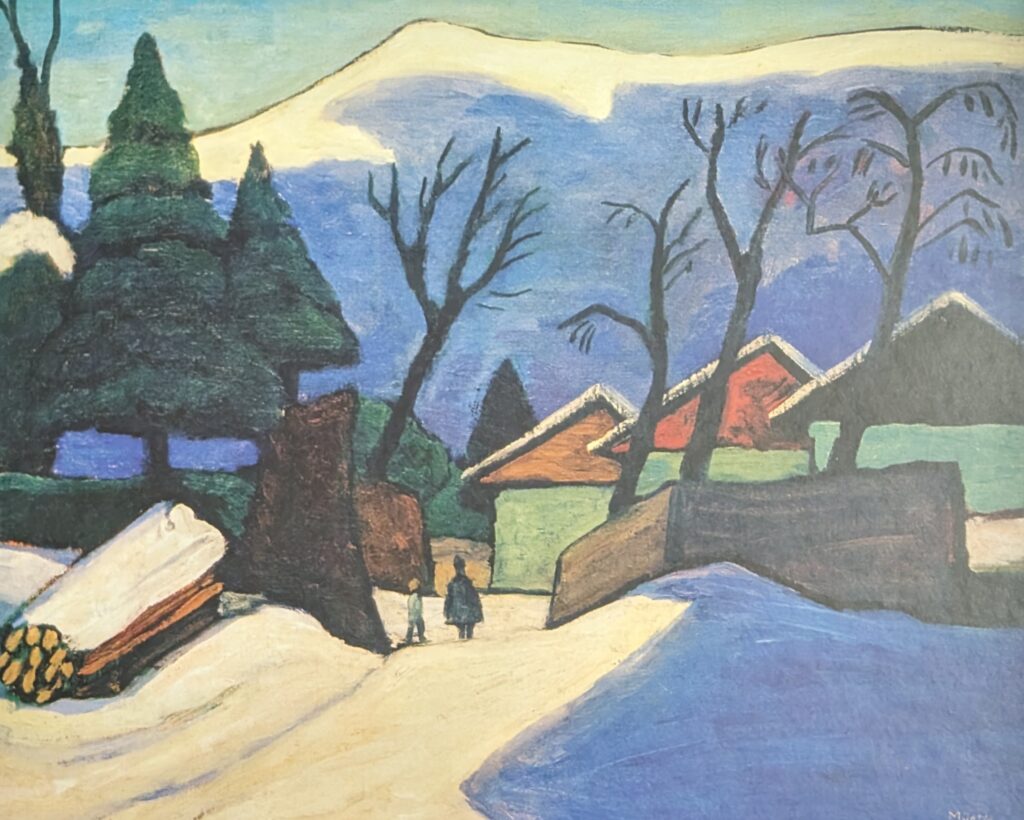

Other notable works of art in the Leopold collection include paintings by the Expressionists Anton Kolig (above left) and Oskar Kokoschka (above right), Richard Gerstl (below left) and the landscape artist Tina Blau (below right).

Gustav Klimt

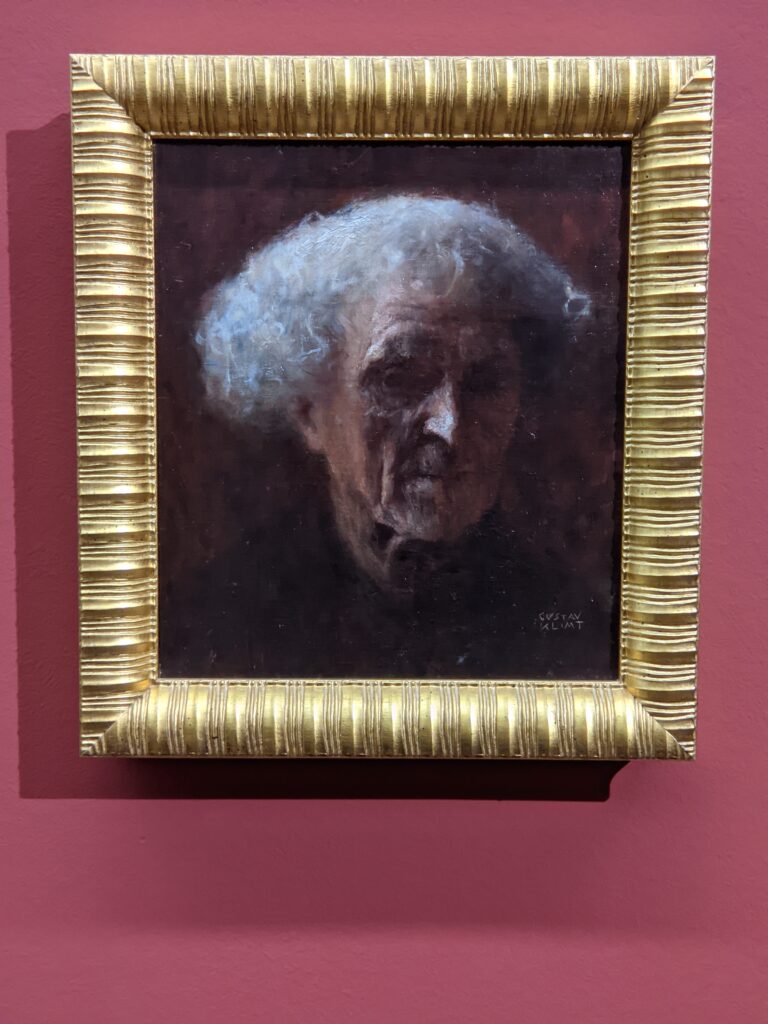

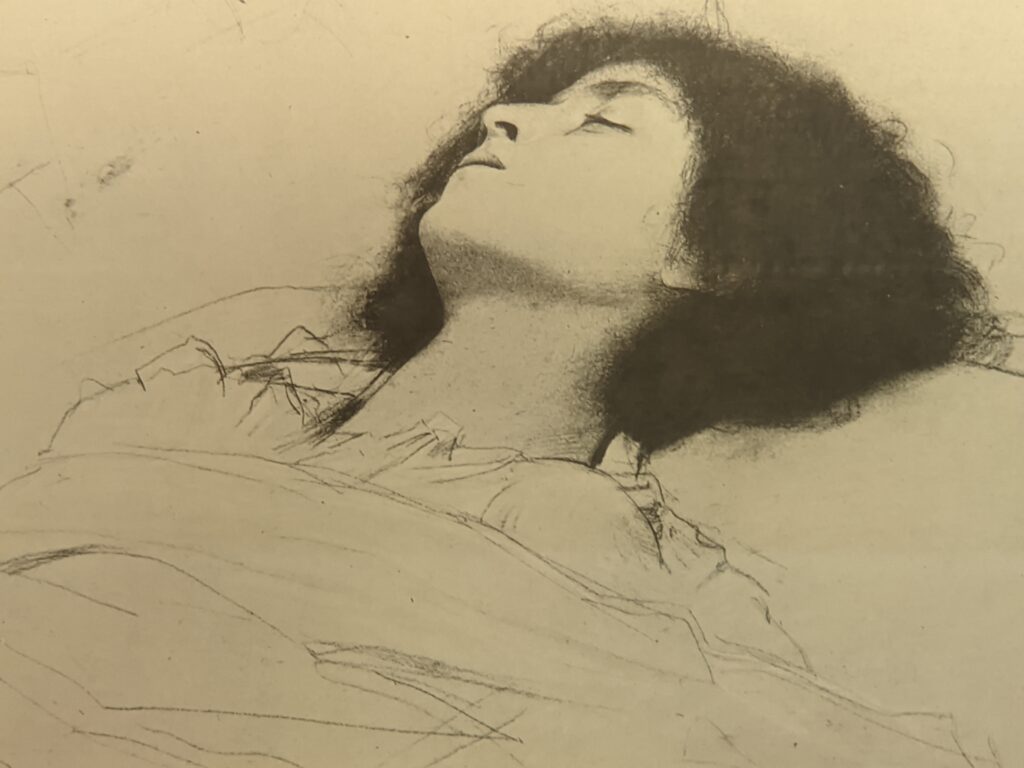

While the Belvedere Museum owns the world’s largest and most impressive collection of paintings (24 in all) by Gustav Klimt (1862 — 1918), the Leopold possesses numerous gems created by Klimt, including “The Blind Man” from 1896 (above left), “Lady with a Lilac Scarf” painted between 1880 and 1882 (above right), and a drawing from 1886 entitled Study for Juliet (below) for the ceiling painting “Theater of Shakespeare” in the Burgtheater.

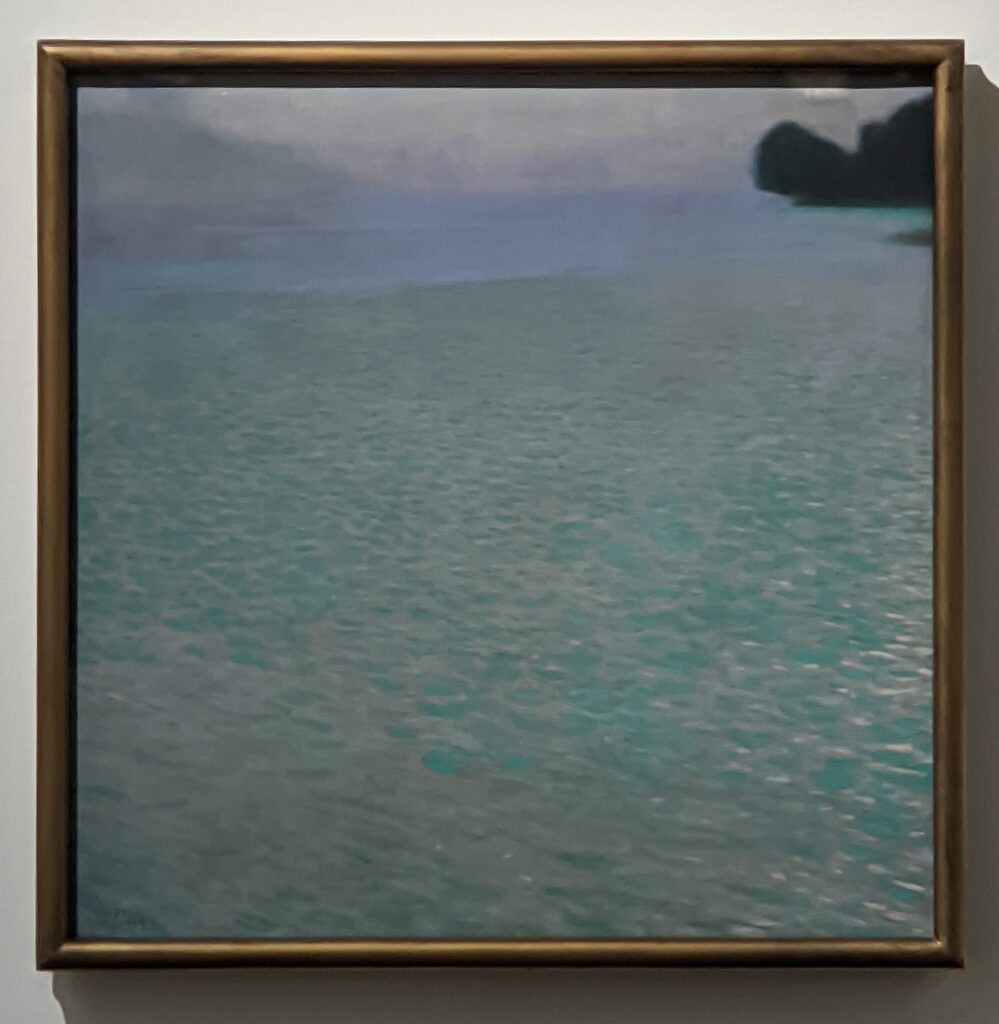

A Masterpiece by Klimt at the Leopold

Gustav Klimt’s masterpiece entitled “Death and Life” would certainly have been of interest to Sigmund Freud. On the right side of this colorful canvas, one finds the positive emotions associated with the Life Drive as described by Freud: love, procreation, affection, harmonious social cooperation — all of which are essential for the continuation of the species. Freud famously declared “the aim of all life is death” and believed that humans have an unconscious desire to die; however, he concluded that instincts from the Life Drive temper most such wishes.

When the World’s Fair was held in Rome in 1911, Klimt’s “Death and Life” won first prize and traveled for exhibit in several European cities. In 1915, Klimt added new mosaics to this famous work and changed the gold-colored background to grey. Unlike Schiele’s portrayal of death, we feel Klimt infused a sense of hope into “Death and Life”: the contented human figures he painted appear to be disregarding the figure of death (on the left) rather than feeling threatened by it.

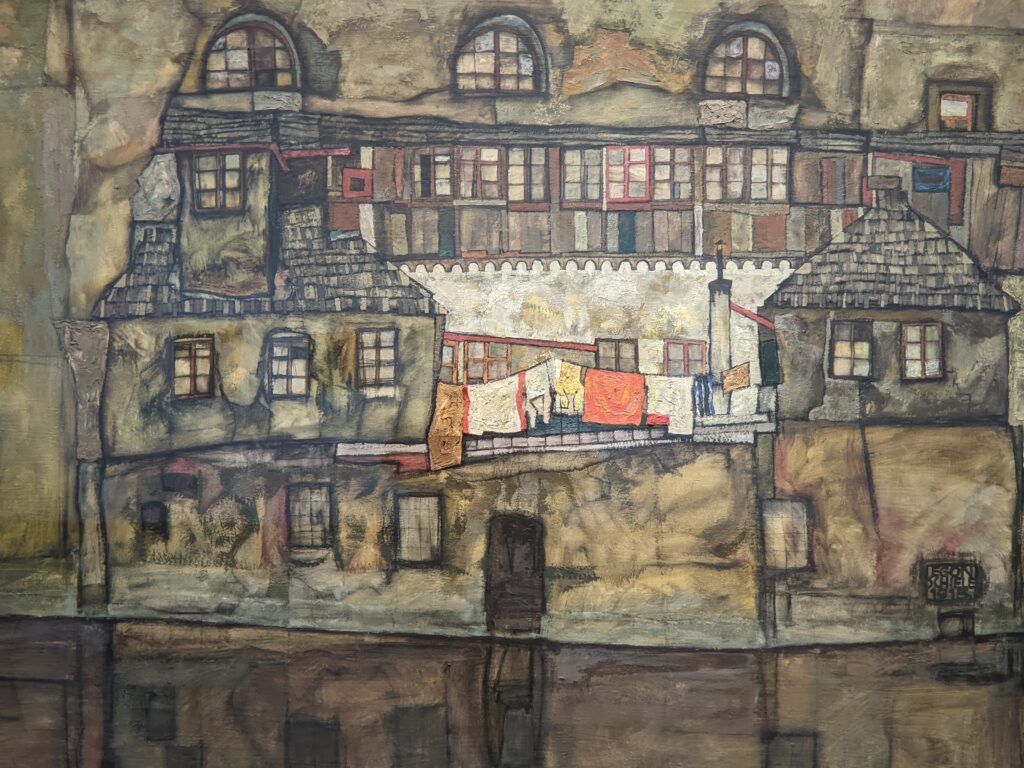

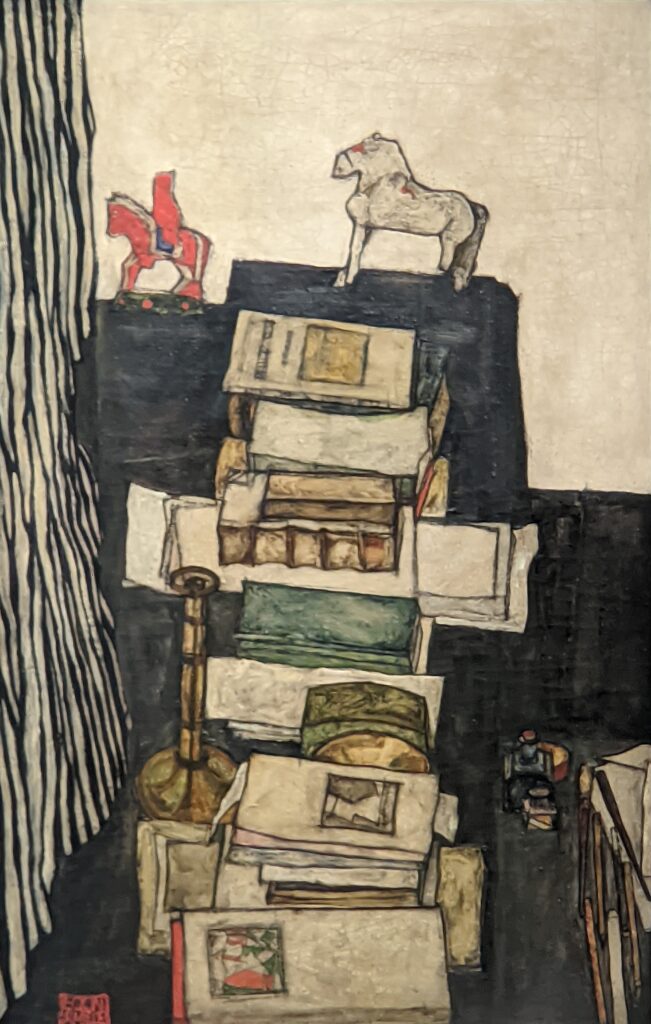

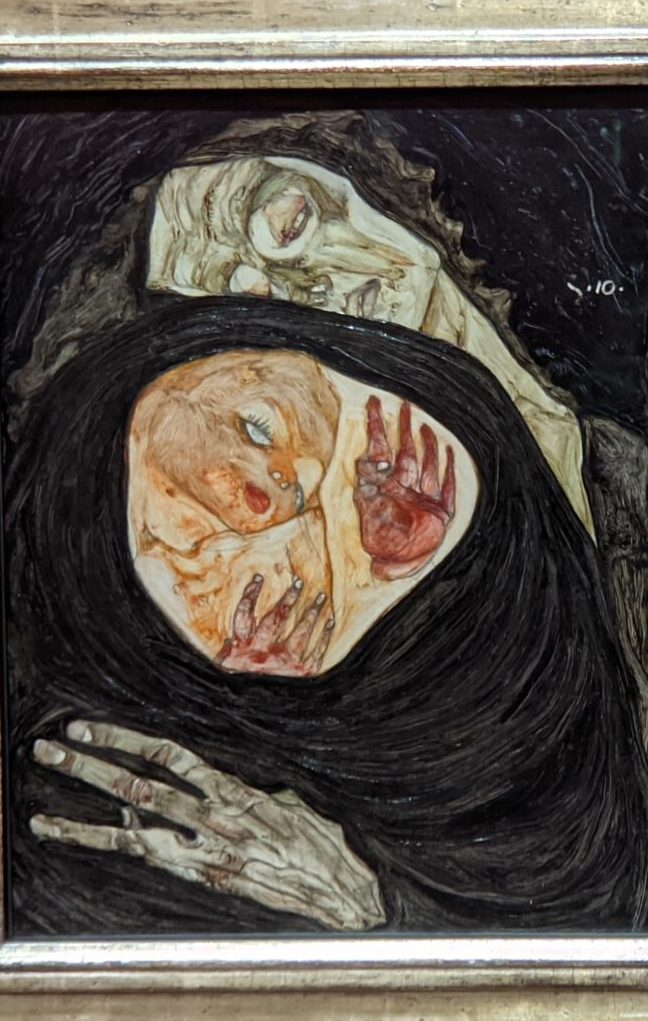

Egon Schiele

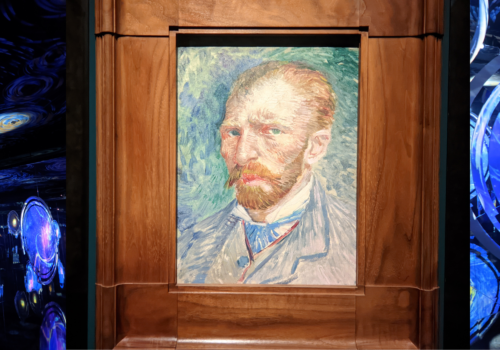

In 1906 (at the age of 16) Egon Schiele entered the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts and within a year met and befriended Gustav Klimt, who would become Schiele’s mentor. Schiele’s early works of art (1907-1909) show the influence of Kokoschka and Art Nouveau, and possess strong similarities with those of Klimt.

Klimt was known for generously guiding the careers of younger artists, and he took a particular interest in the talented and highly promising Schiele (who was 28 years his junior). In 1909, Schiele left the Vienna Academy and (at Klimt’s invitation) exhibited his art at the Vienna Kunstschau, where Schiele experienced his first encounter with paintings by Vincent van Gogh (to whom Schiele painted tributes) and Edvard Munch. In the following year, Schiele would altogether abandon the Jugendstil style of the Secession.

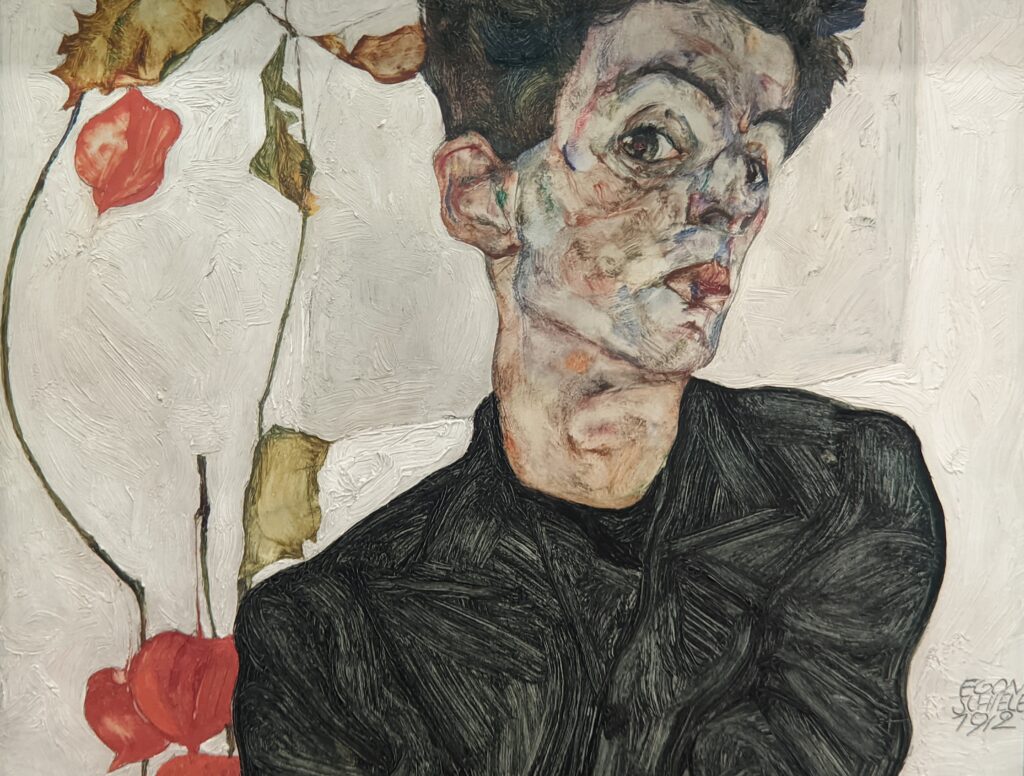

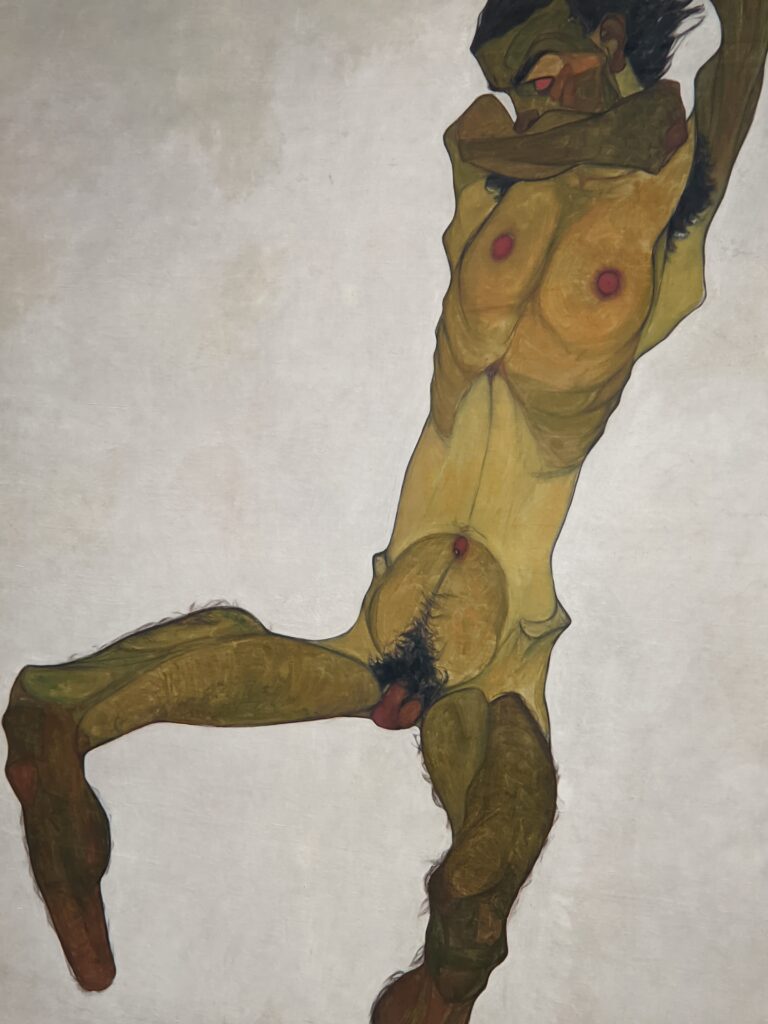

1910-1912: Marked Success for Schiele, a Radical Turn to Expressionism & Scandal

Free from the constraints of the Academy, Schiele began painting nudes and within a year developed his own unique and definitive style featuring figurative distortions of the human body and unprecedented sexual openness. Though his previous art was considered daring, by 1910 Schiele took even bolder steps forward, creating naked figures with bodies that appeared deformed with emaciated, discolored and elongated limbs and fingers. At this time, he also began drawing and painting children.

In 1911, Schiele and Walburga Neuzil (his 17-year-old model, muse and lover) left Vienna and settled in a small town in Bohemia, where residents strongly disapproved of his employment of teenage girls as models and soon drove the couple out of town. Meanwhile, in Vienna, the first one-man show of Schiele’s art took place at a prestigious gallery. Schiele set up an inexpensive studio in another small municipality 35 km west of Vienna and was subsequently arrested on charges of abusing a girl under the age of consent, and he spent 24 days in prison. From Schiele’s studio, the authorities seized more than 100 drawings (deemed pornographic) and at trial the judge burned one of the drawings over a candle flame in the courtroom. Even though Schiele was acquitted of the charges relating to seduction and abduction of a 13-year-old, he was found guilty of exhibiting erotic drawings in a place accessible to children, and this scandal was never completely forgotten.

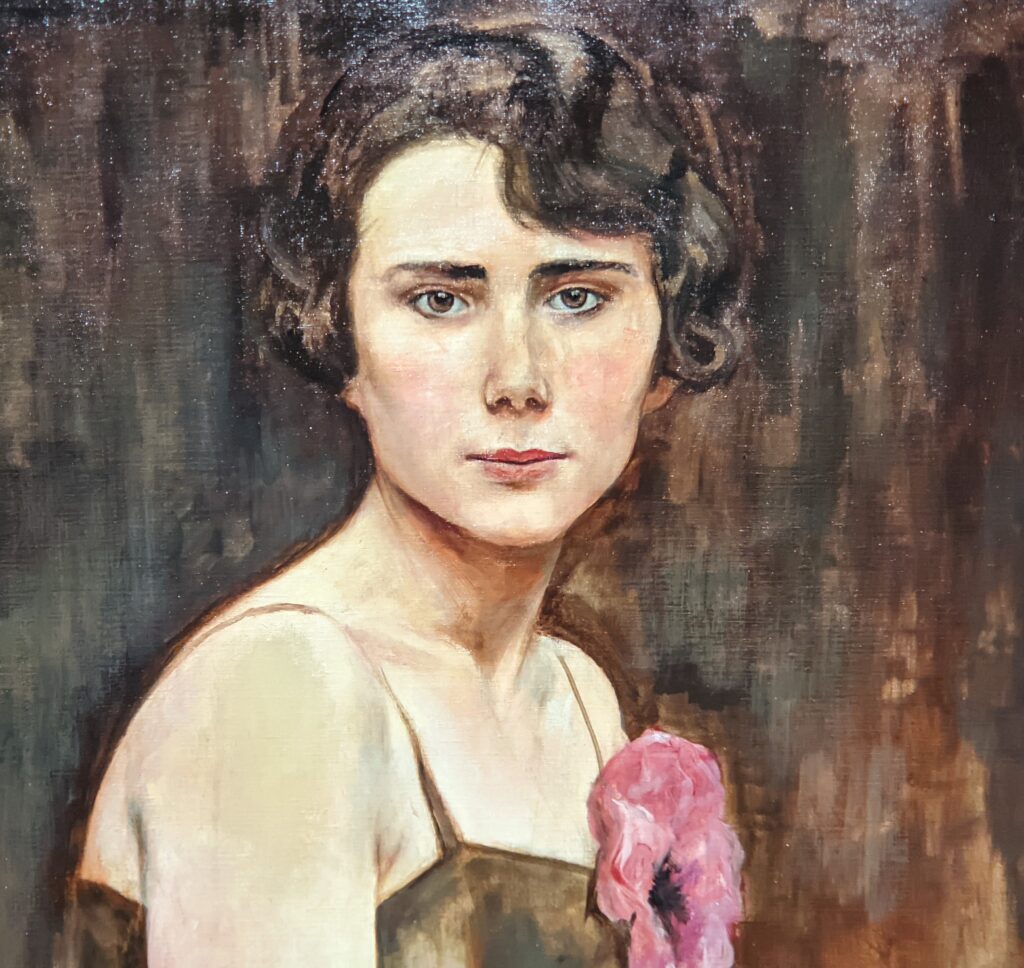

Walburga (Wally) and Egon were lovers from 1911 to 1915. The Leopold owns the best-known portrait of Wally Neuzil (above) created by Schiele in 1912 when he was nearing the height of his artistic prowess — even though Schiele was only 22-years-old. A gallery in Munich presented the first international solo exhibition of Schiele’s output in 1913, and another solo featuring his works of art was held the following year in Paris.

In 1914, Egon Schiele took notice of Edith Harms, who lived with her family across from Schiele’s art studio, and in 1915 they were married. When Schiele explained this romance to Wally Neuzil, Wally left him immediately. They never saw each other again.

Egon Schiele saw his wife Edith on occasion after he was conscripted into the military service in World War I. He continued to draw, paint and exhibit during the war and, in 1917, he returned to Vienna to focus on his career.

Leopold — The Best Place to Appreciate an Artist Who Was Ahead of His Time

Like Francisco Goya y Lucientes (1746 — 1828) before him, Egon Schiele was an exceptionally creative individual whose art may best be described as ahead of the time in which the artist lived. As an alternative to conventional ideas of beauty, Schiele often interpreted the human form by using figural distortion. Many people in 1912, including most scholars and even the most progressive thinkers, found the explicitness of such art works disturbing — and over 110 years later you may arrive at the same conclusion. Some of these paintings and drawings, at first glance, do appear deeply disturbing. The point is that Egon Schiele’s art remains fresh, powerful and relevant despite the passage of time. After substantial consideration and reevaluation, we prefer to consider Goya and Schiele as visionaries.

Triumph & Tragedy

Schiele’s creative output from 1917 to 1918 was prolific, and his new paintings reflected the maturity of an artist in full control of his talents. In 1918, 50 works of art by Schiele were displayed in the 49th Exhibition of the Vienna Secession. This exhibit marked another triumph for Schiele: many of his paintings sold, prices increased for his drawings, and he received many commissions for portraits.

Edith Schiele was six months pregnant in the autumn of 1918, but she died during that year’s influenza pandemic which took more than 20,000,000 lives in Europe. Egon Schiele at age 28 succumbed to the same disease three days later.

Schiele: An Excellent Candidate for Analysis

During his short lifespan, Schiele created almost 300 self-portraits.

The art of Egon Schiele is more than simply provocative — it is thought-provoking, beautiful at times, extremely interesting, and certainly challenging. The same could be said for the art of Robert Mapplethorpe (1946 — 1989). The work of both artists featured an array of subjects: portraits and self-portraits, male and female nudes, and still-life images, flowers in particular. Both artists were gifted at illustration, and the art they created was deeply personal, introspective and, therefore, in our opinion honest. The technical skill of these men is undeniably flawless, to the point where the viewer’s attention immediately shifts to the subject matter. Thus, it is perhaps the subject matter chosen by Schiele and Mapplethorpe that arouses enormous public interest and curiosity, holds the attention of art lovers over time, and demands our analysis.

Is Egon Schiele a good candidate for analysis?

We assume Sigmund Freud would scream “Yes!”

In fact, for Freud this proposition might have represented a dream come true.

The Leopold Highlights Achievements by Female Artists

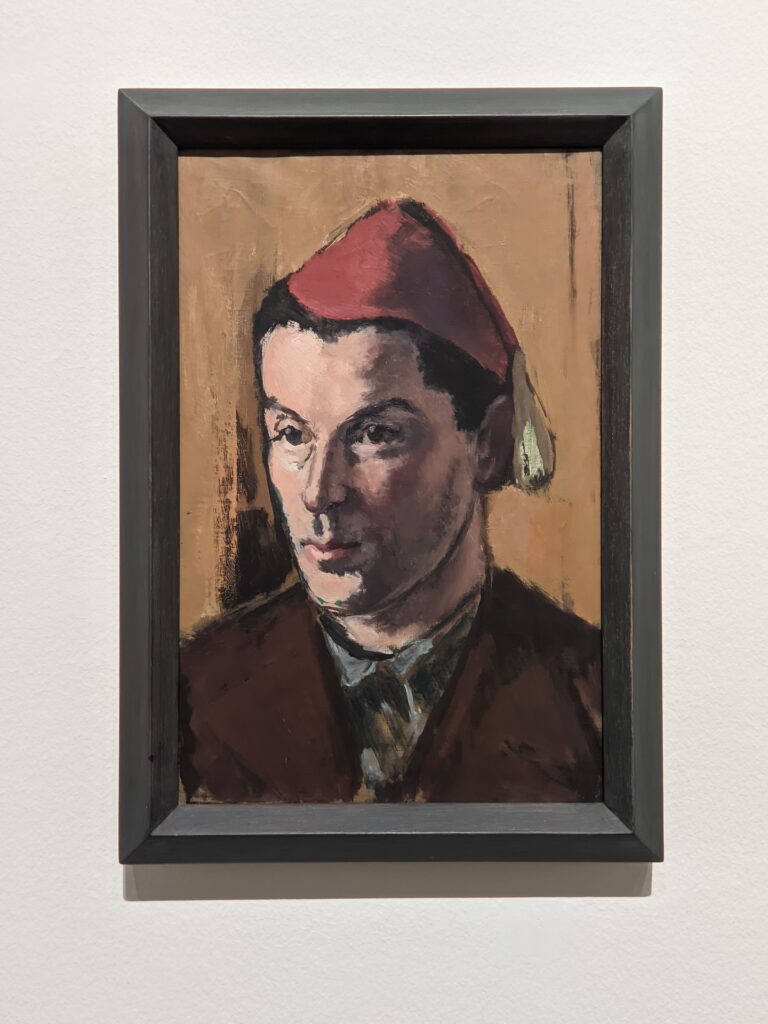

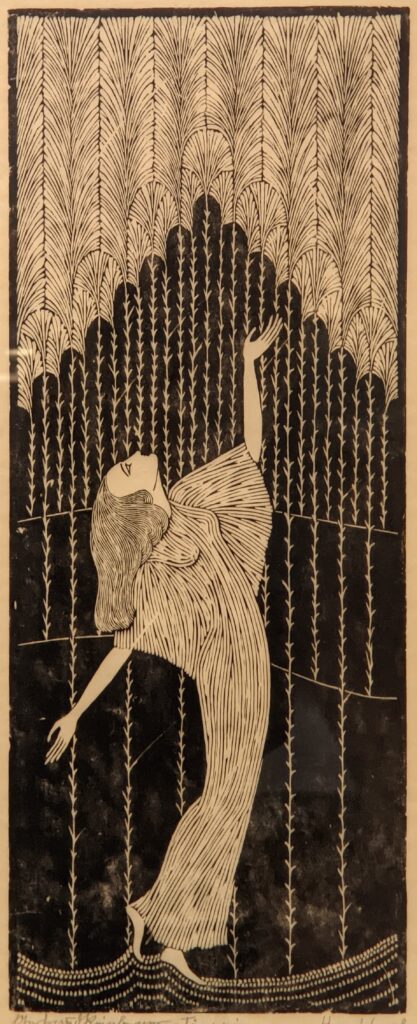

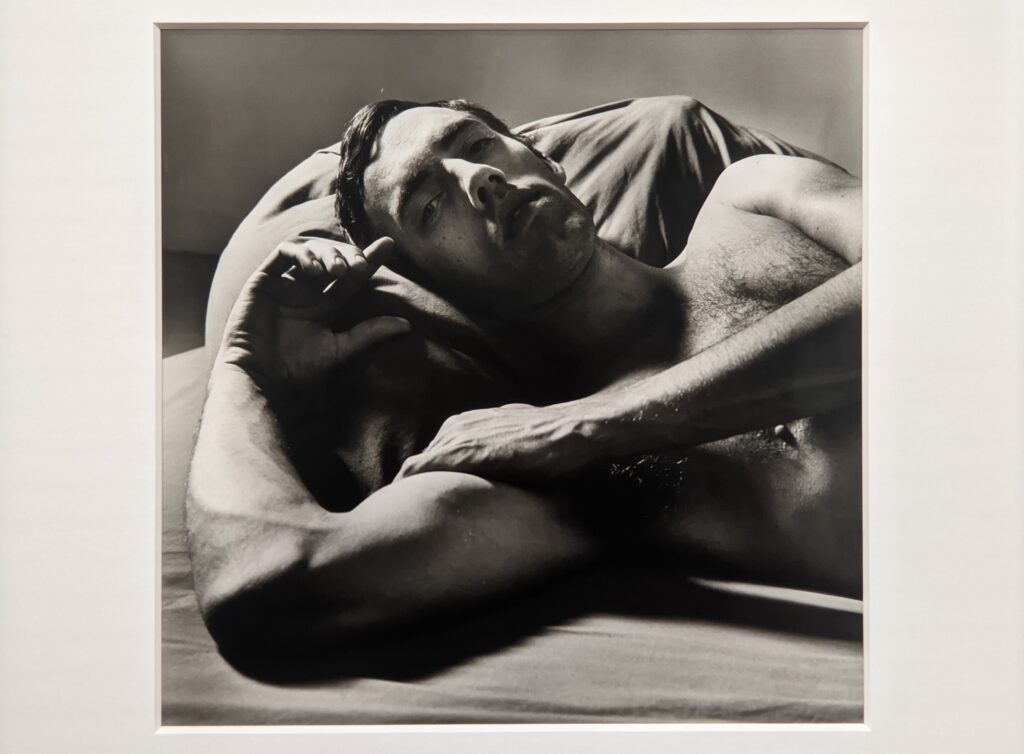

Many interesting works of art by gifted women have been displayed at the Leopold, including “Portrait of a Young Man in Red Cap” (above left) from 1928 by Marie-Louise Motesiczky”; “Young Woman in Front of a Bird Cage” (above right) from 1907 by Broncia Koller-Pinell”; “David Wojnarowicz at Home” from 1990 (below left) by Nan Goldin {cibachrome print}; and “Female Dancer” (below right) by Gertraud Reinberger-Brausewetter {woodcut on Japanese paper}.

Something for Everyone — Exhibits from Traditional to the Avant-garde at the Leopold Museum

The Leopold enhances its substantial holdings by presenting topical temporary exhibits exploring diverse mediums, including photography (above left & below).

Past Exhibitions in 2024 at the Leopold Museum

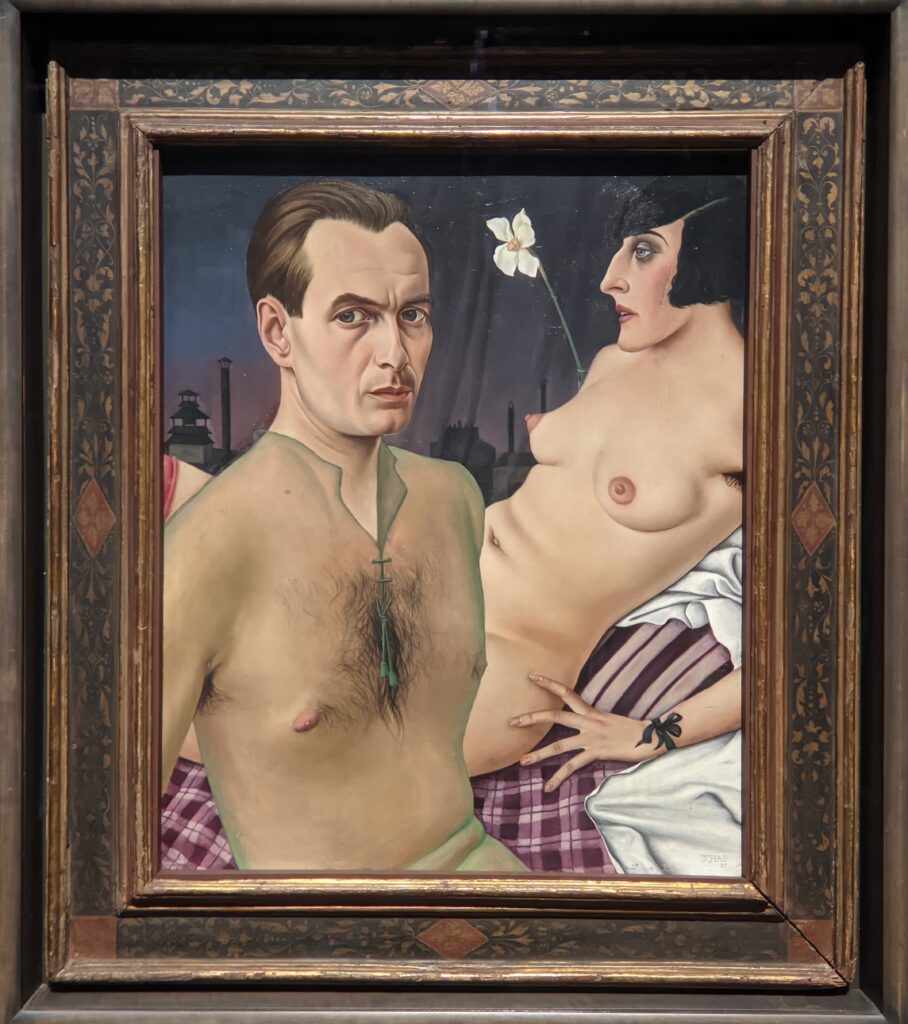

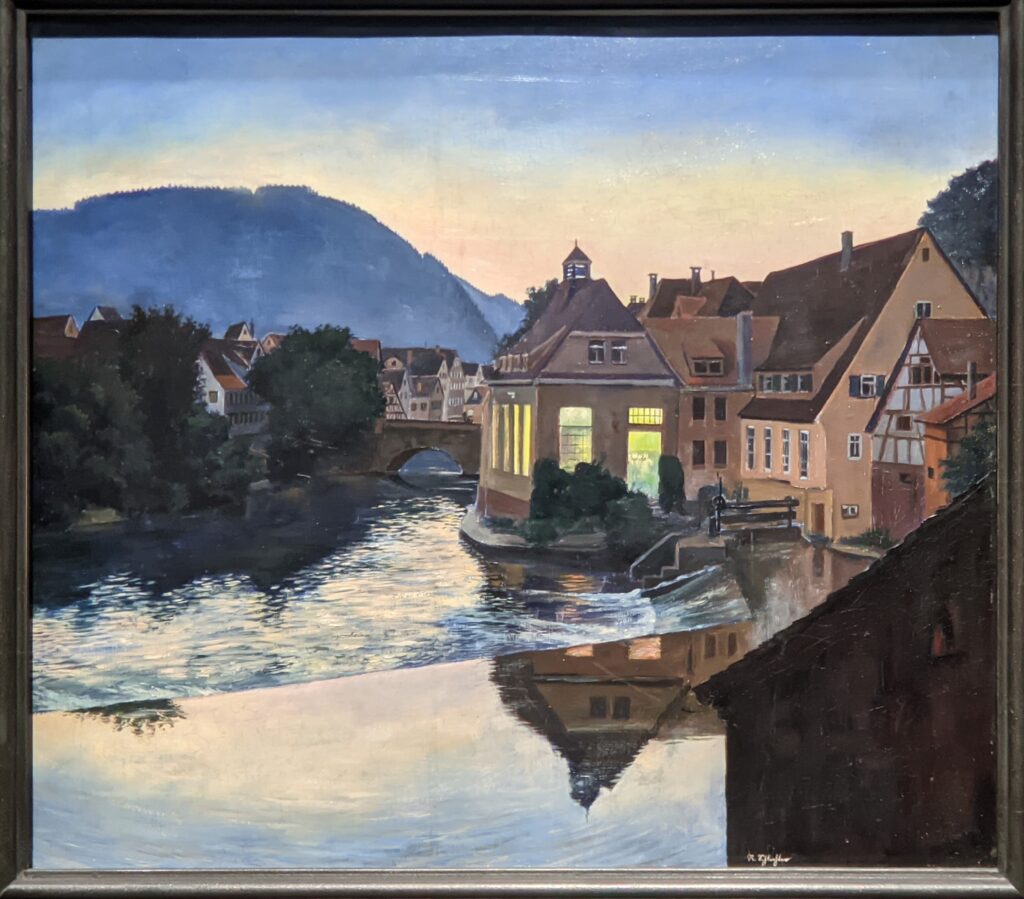

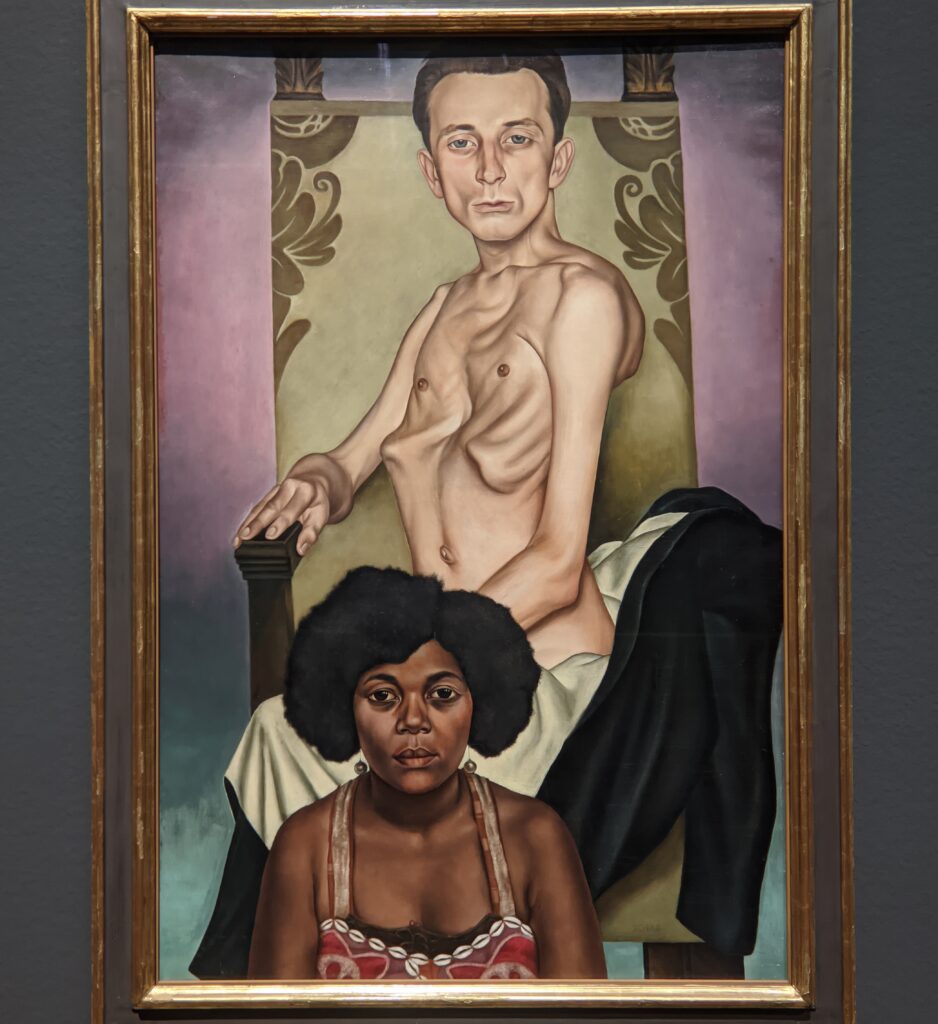

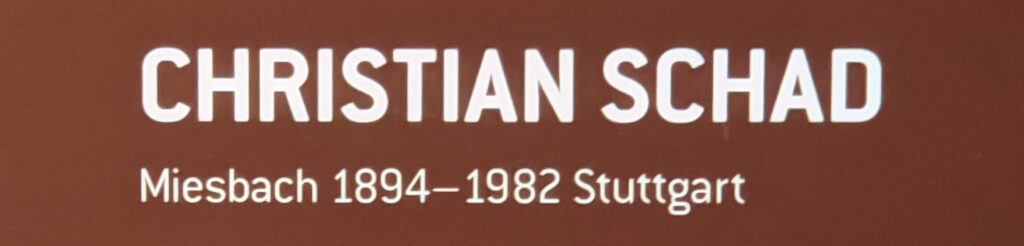

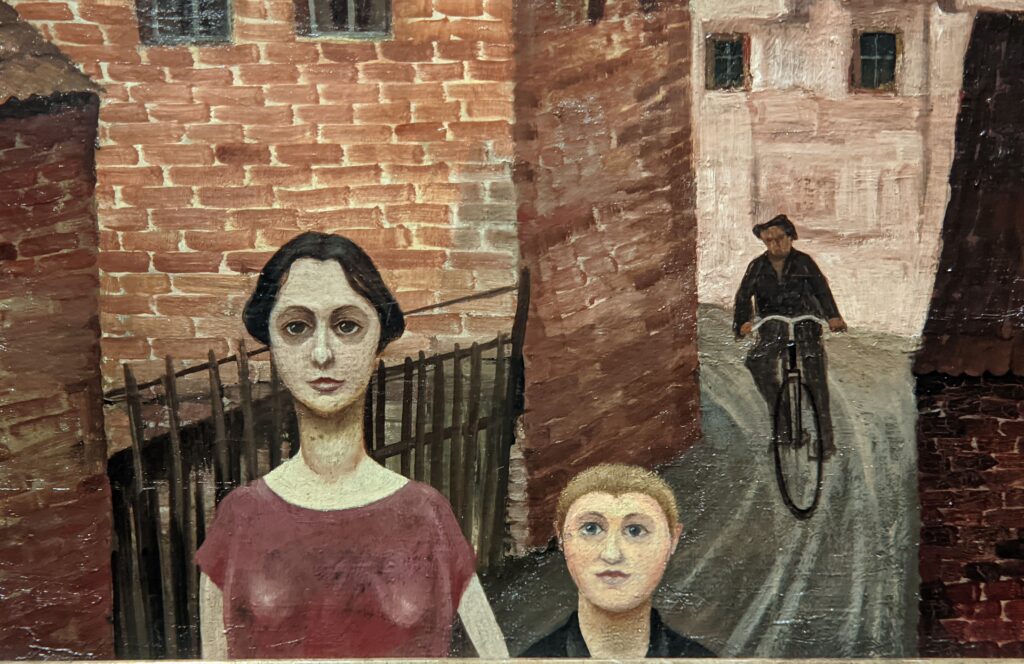

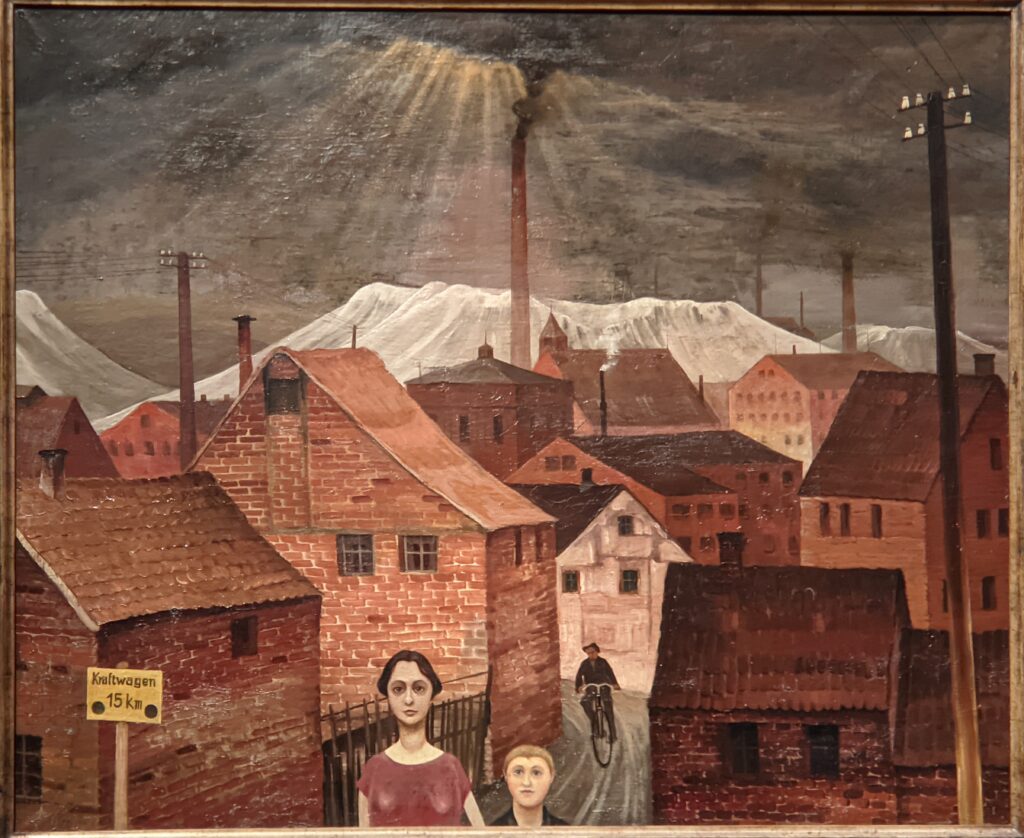

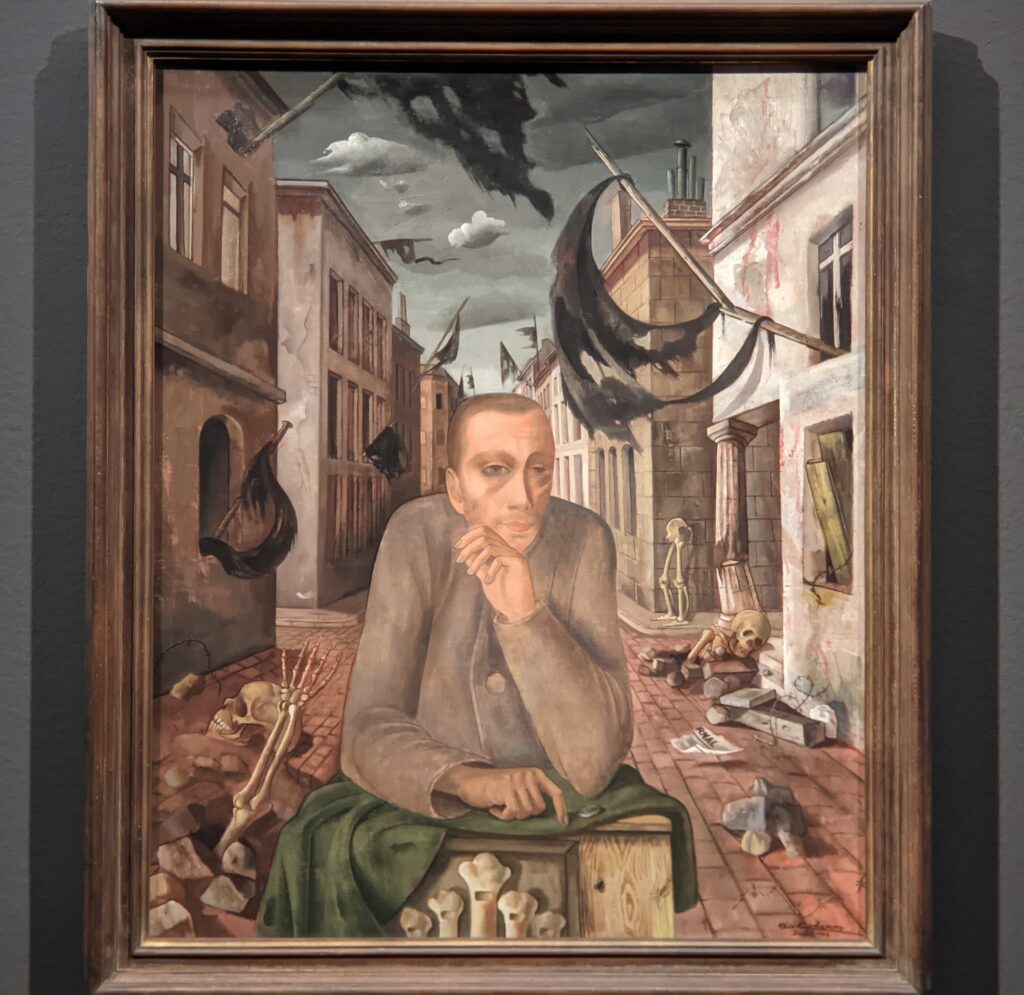

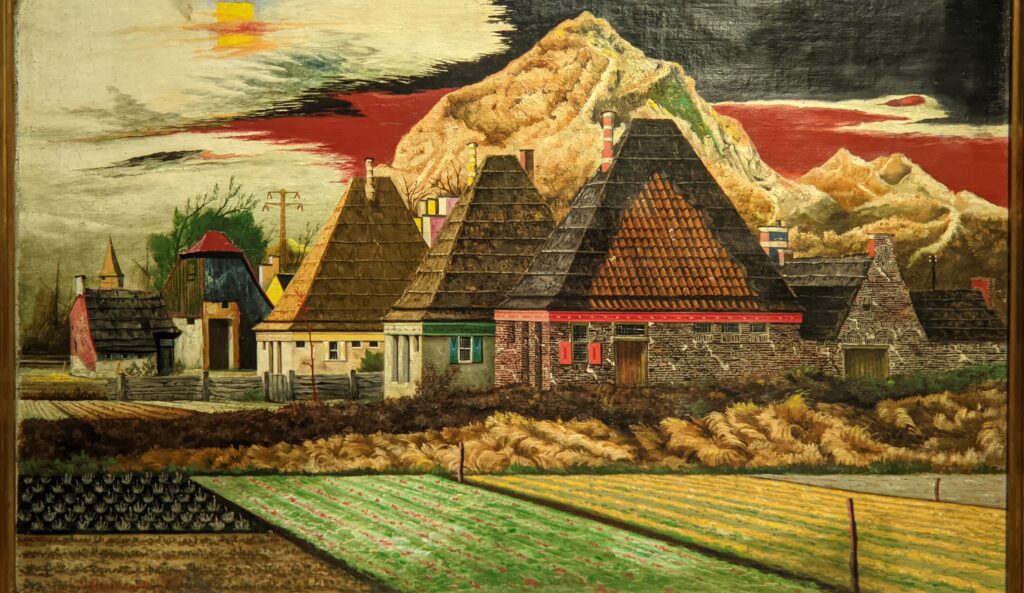

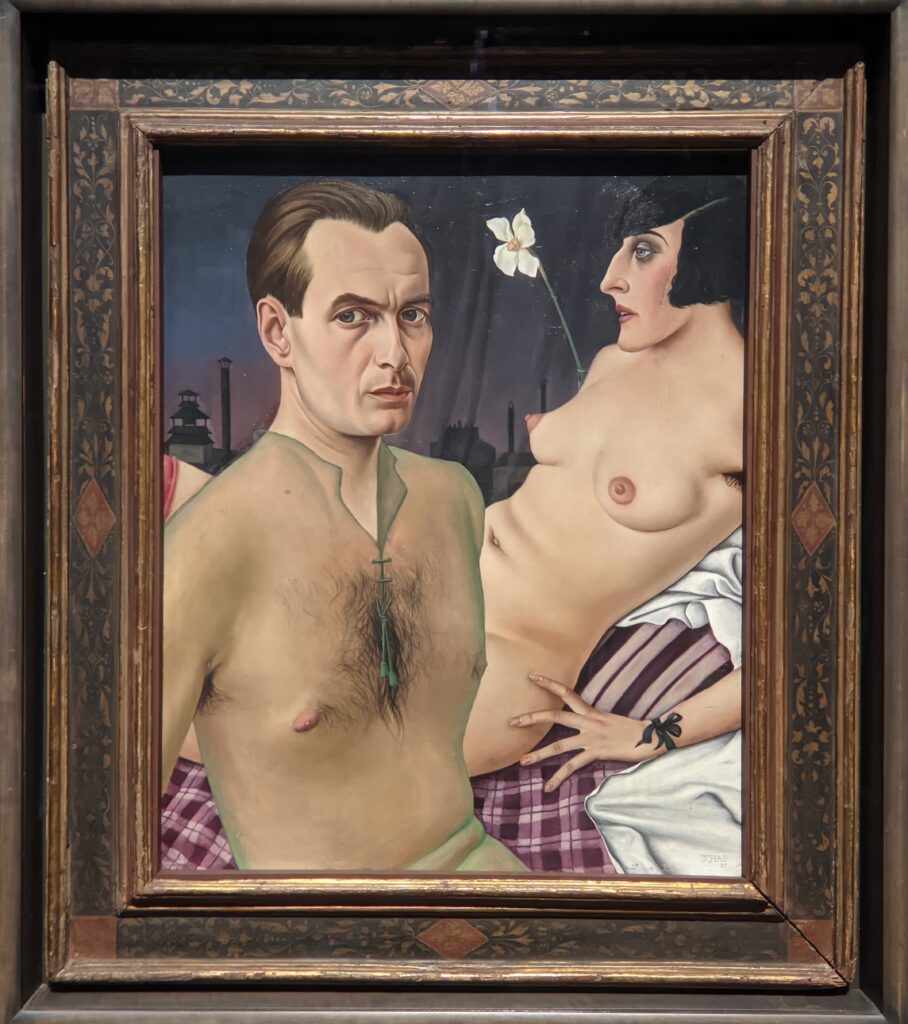

The exhibit “Splendor and Misery” offered a rare opportunity to appreciate Christian Schad, a uniquely gifted painter. The physical (as well as the psychological) devastation of World War I, claiming more than 9,000,000 lives and leaving 20,000,000+ wounded, beckoned visual artists to create a new depiction of reality. One response in the world of art was the “New Objectivity” movement in Germany, which adopted an unsentimental, concrete and sober expression of life during the 1920s — art both realistic and objective — and rejected the romantic idealism and expressionism that preceded it. Schad and the other artists (shown below) who joined “New Objectivity” depicted people and things in a distant and sharp manner, and chronicled the conditions in Germany during the Weimar Republic (1918 — 1933), especially the hardships, hope and developments of that era.

The New Objectivity movement ended in 1933 with the rise of the Nazi dictatorship and its enforcement of a new policy concerning art, i.e., artists who were politically suspect endured raids on their studios / homes, exclusions from associations and institutions, as well as bans from exhibitions and employment. Artists were murdered, forced into self-censorship or exile, or capitulated to the art policy of the Nazi regime.

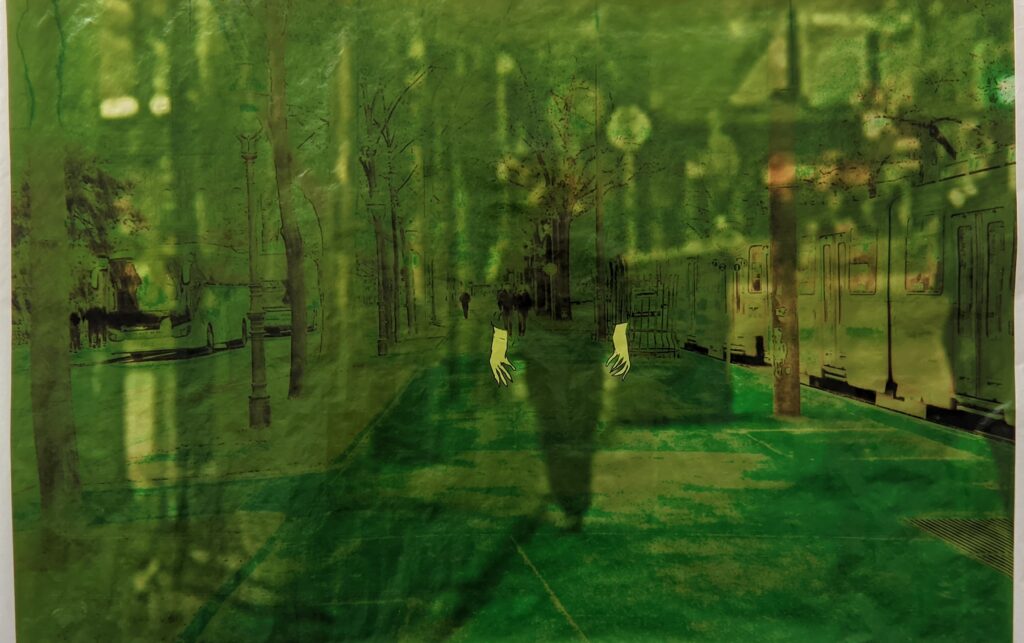

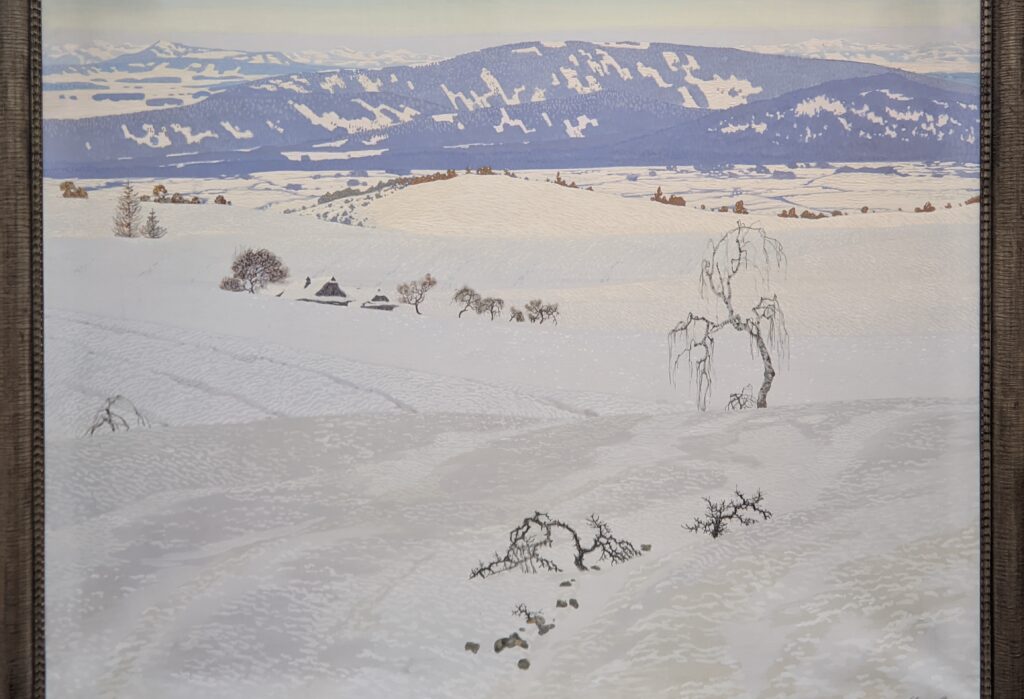

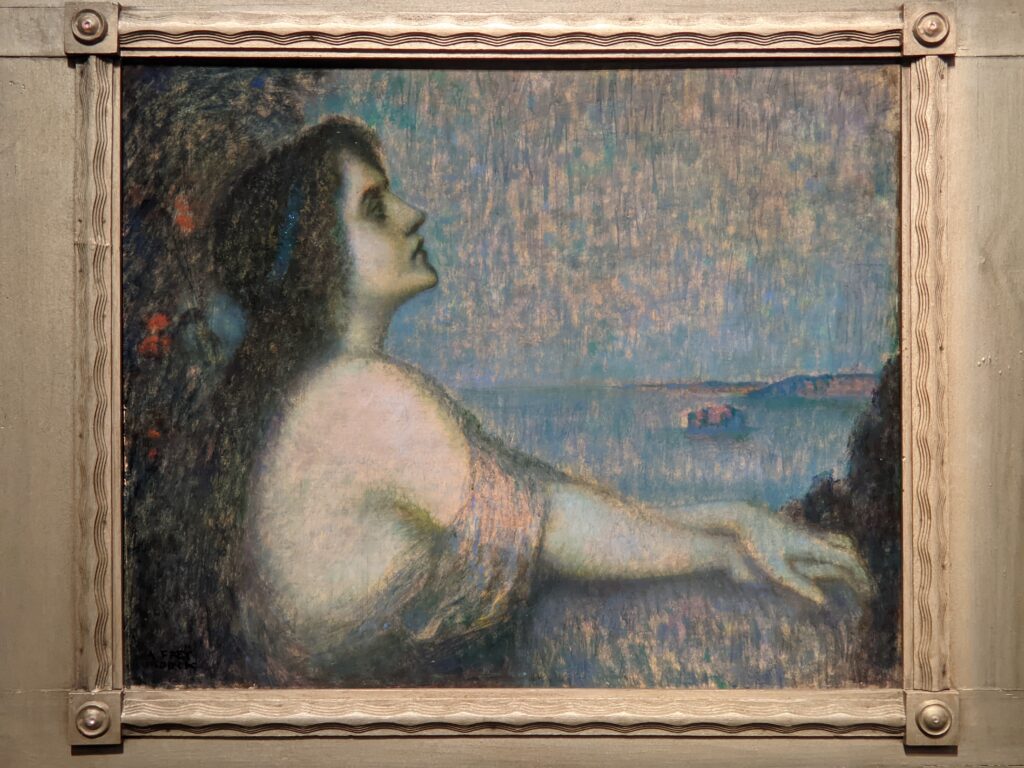

The exhibition entitled “Unknown Familiars” (from May through October 2024) brought together over 200 works of art encompassing various genres from different periods. The show united artistic highlights — including Milos Jiranek’s 1900 Study of a Swimmer, below — from 6 corporate collections within the Vienna Insurance Group.

Retrospectives at the Leopold Museum: Gabriele Münter, Max Oppenheimer, Hagenbund & Wittgenstein

More than 100 works of art, including graphic pieces, photographs and oil paintings, by Gabriele Münter were shown at the Leopold in 2024 as part the first comprehensive retrospective in Austria of her career.

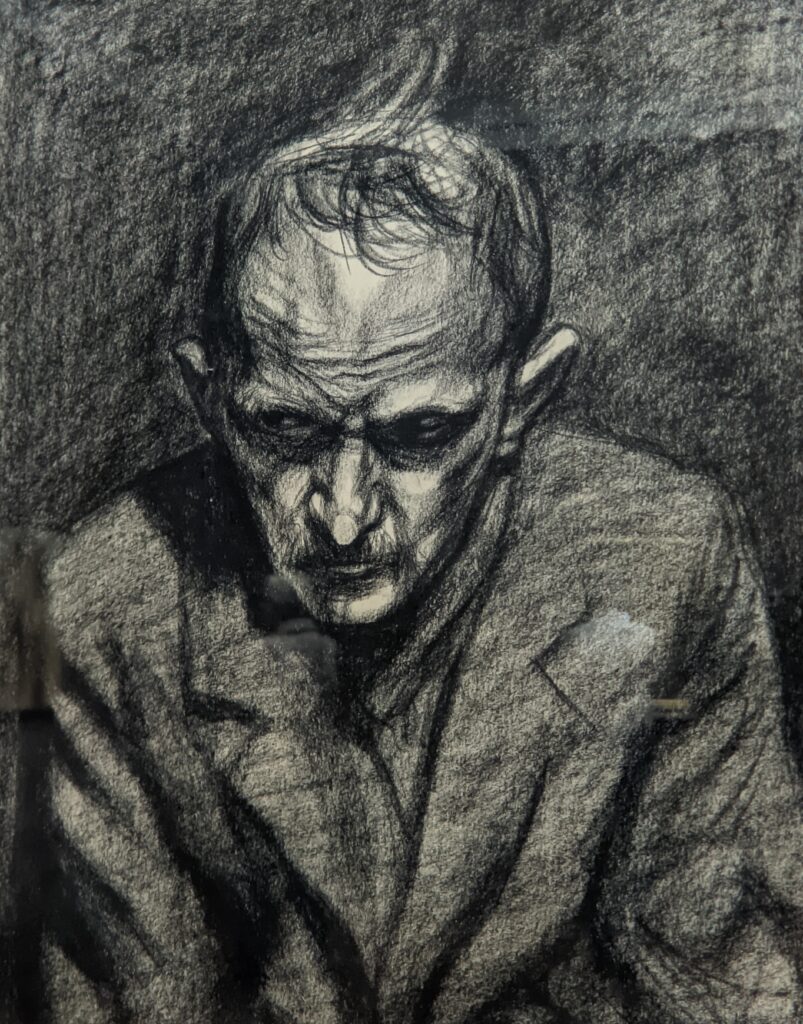

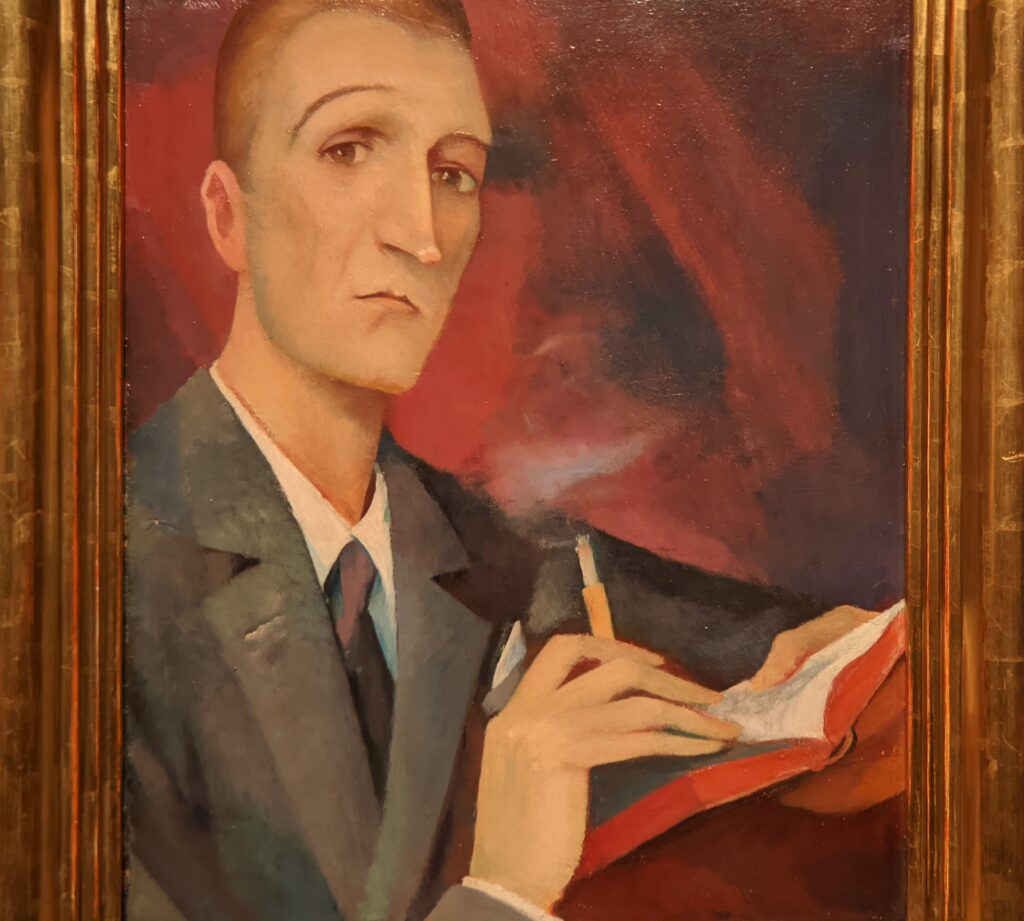

Max Oppenheimer

The Leopold Museum presented “Max Oppenheimer — Expressionist Pioneer” until February 2024. Born in 1885 in Vienna, Oppenheimer was forced to flee Austria in 1938 when German troops invaded the country. From Switzerland he emigrated to the United States, where he died penniless in 1954.

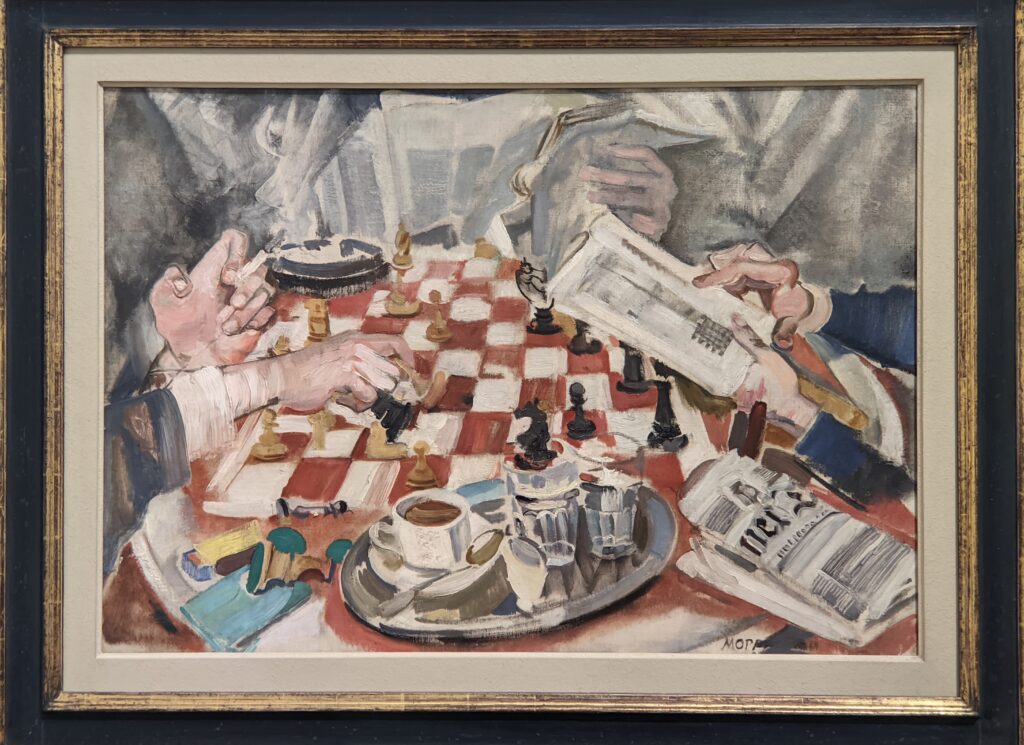

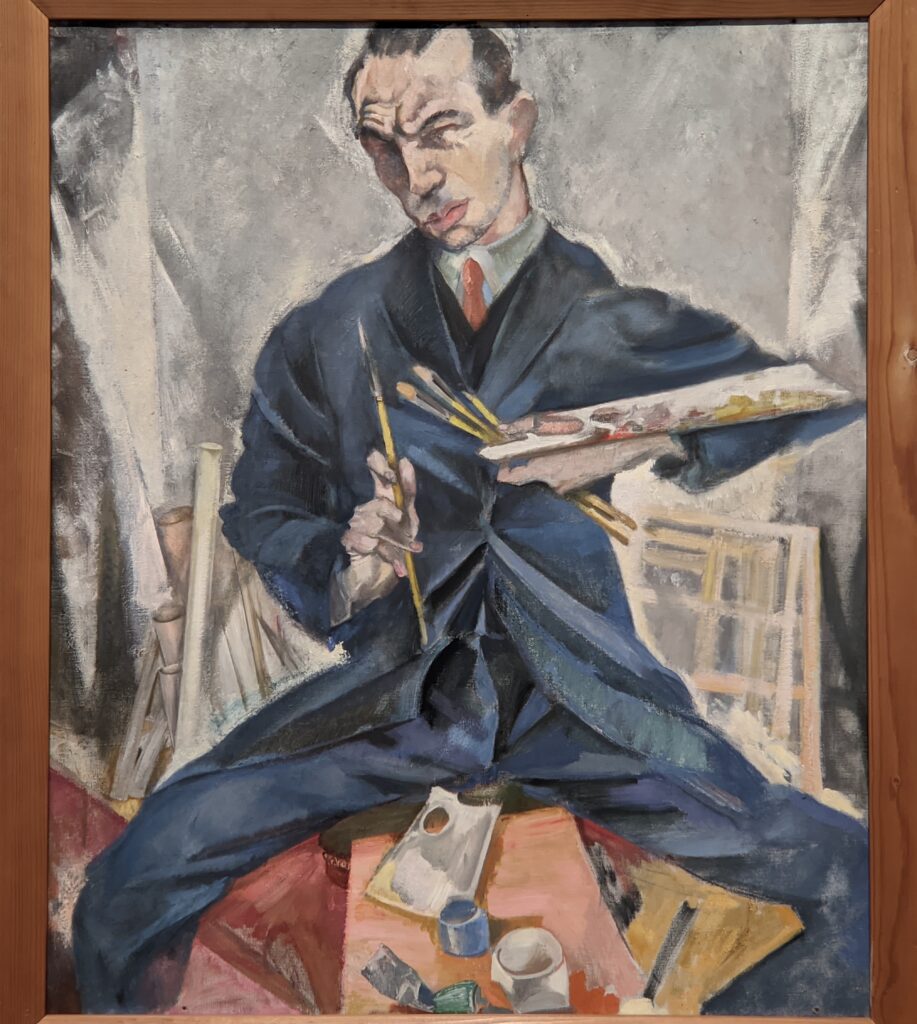

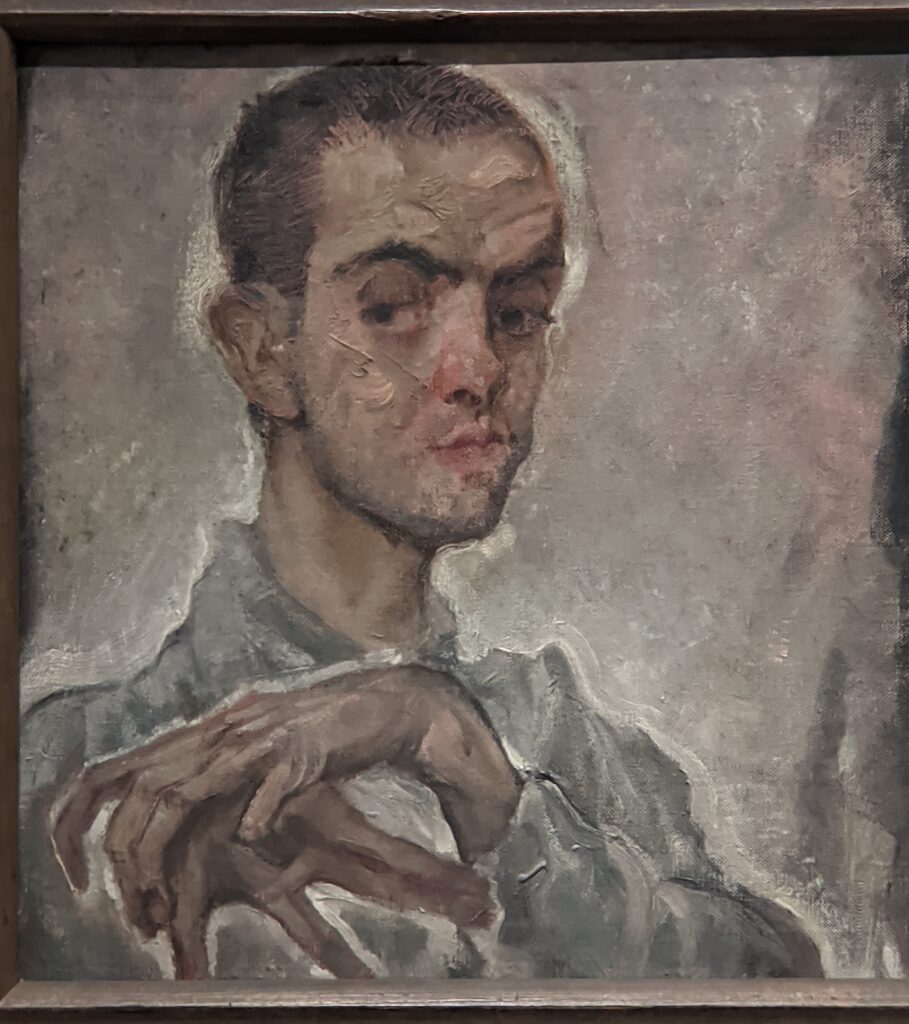

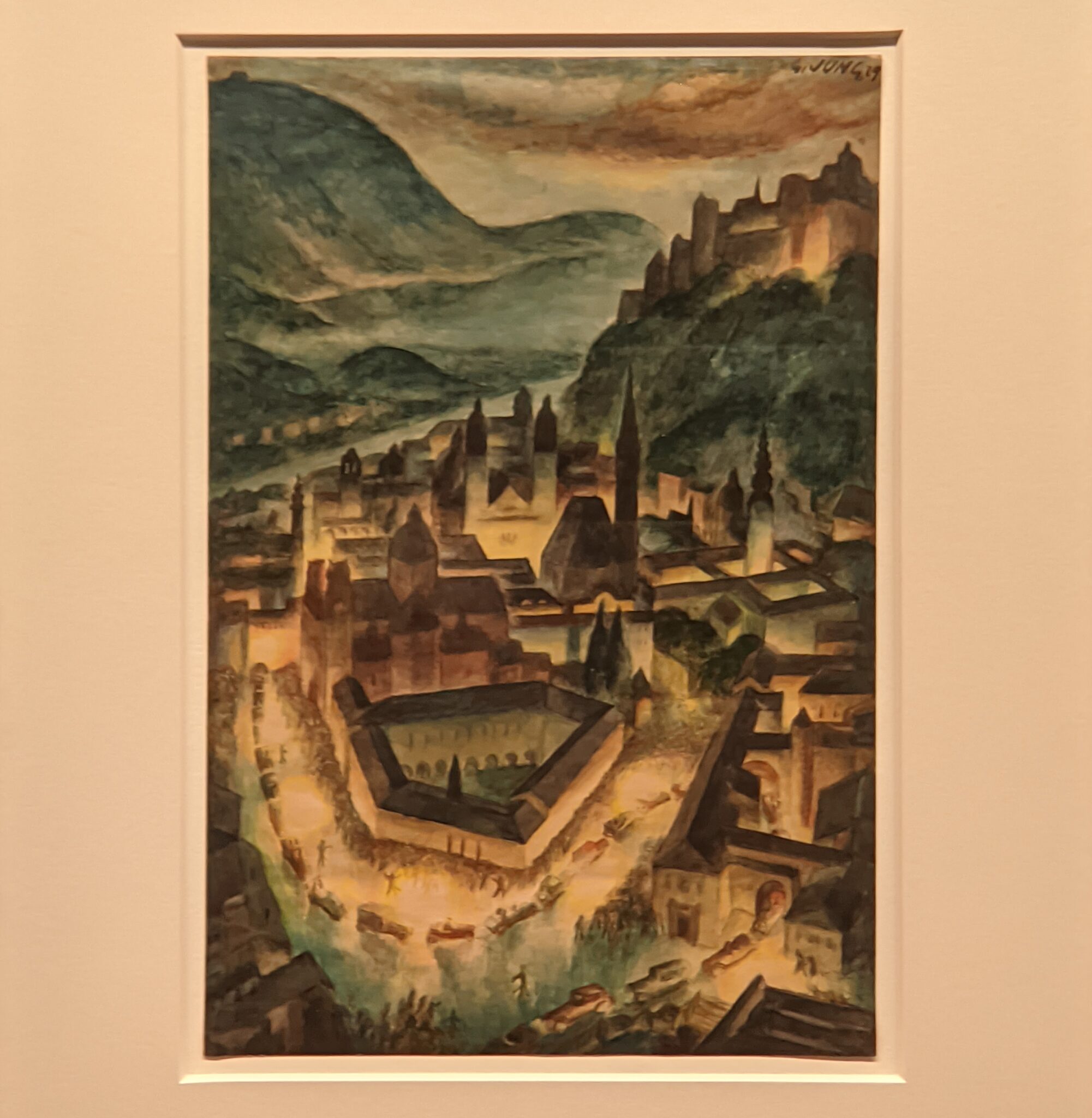

The exhibition “Hagenbund” closed at the Leopold in 2023.

The Hagenbund was an association of modernist artists active in Austria between 1900 and 1938. Beginning in 1902, these innovative painters found a home for exhibitions inside the Zedlitzhalle (photo above), a refurbished market hall in Vienna’s 1st district. The building’s 400 square meters of interior space allowed for the display of collective exhibitions in addition to shows of renowned international artists, such as Arnold Böcklin in 1903 — the same year Emperor Franz Joseph I came to see a Hagenbund presentation.

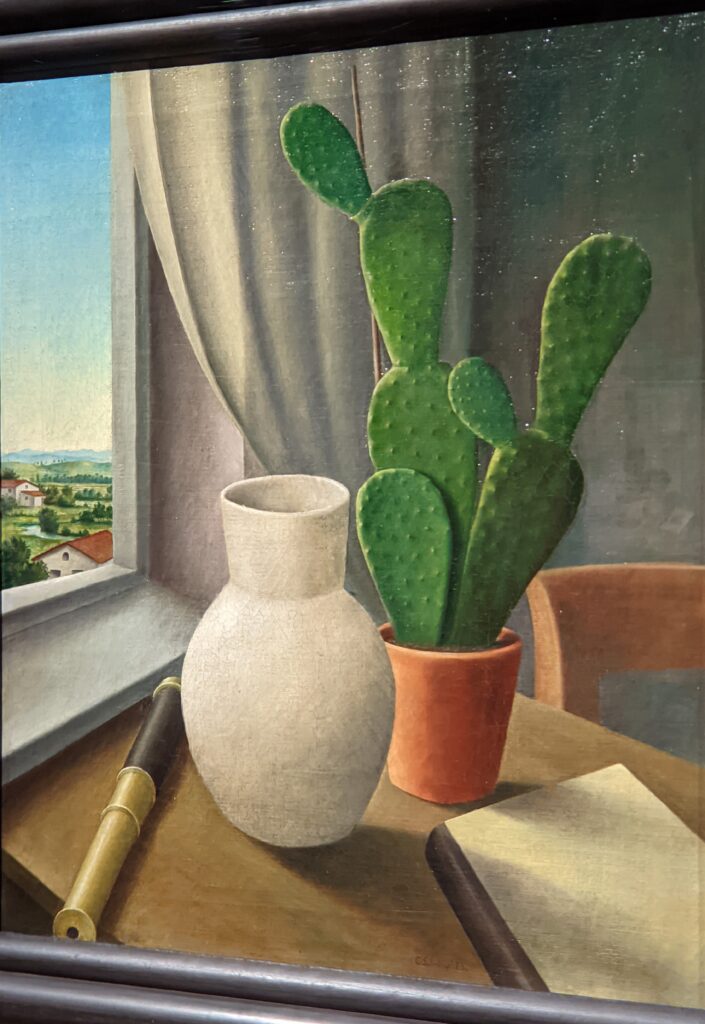

Anton Faistauer created “Still Life with Coffee Cups” (below) in 1912. The Hagenbund’s presentation of artwork by Faistauer, Oskar Kokoschka and Anton Kolig advanced its popularity and reputation.

By 1910, the Hagenbund had become the pre-eminent platform for contemporary art in Austria, but public outcry against the exhibition of radical art would ultimately result in the cancellation of their lease at the Zedlitzhalle. The last exhibition held there, in 1912, featured several major works by the 21-year-old Egon Schiele. The ecological downside of rapid industrialization and the social unrest that resulted from the nationalist tendencies prevalent in Europe on the eve of World War I influenced the dynamism of the Hagenbund, which returned to exhibiting at the Zedlitzhalle in 1920. Guest exhibitions by artists from Prague and Budapest made the Hagenbund the leading platform in Vienna for an international avant-garde, and graphic works by Matisse, Braque and Picasso were exhibited in 1927.

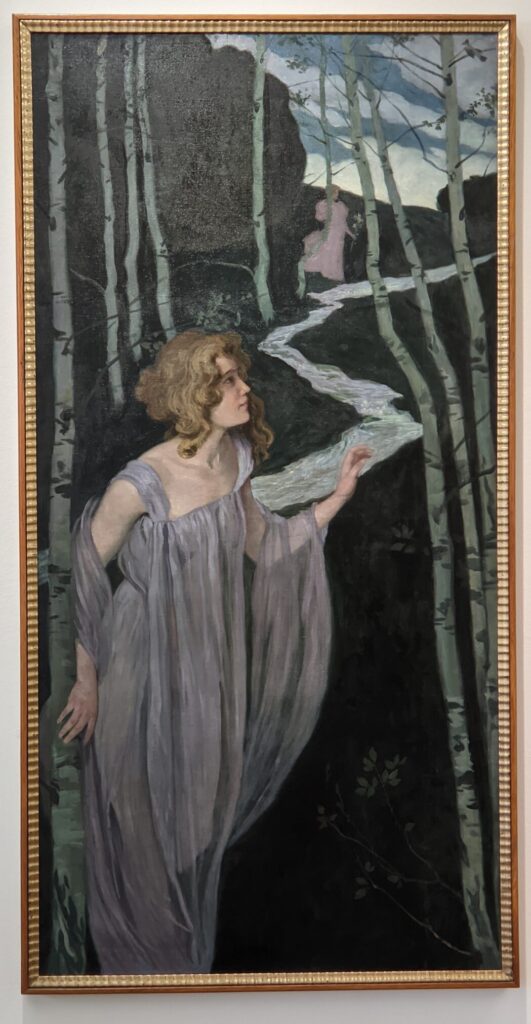

Members and supporters of the Hagenbund were not bound by a manifesto or limited to one style of art. While the founding Hagenbund artists were chiefly proponents of plein-air painting, Symbolism and Jugendstil, after World War I these painters, sculptors and ceramicists became increasingly progressive, espoused variants of New Objectivity and shared post-Expressionist tendencies with Fauvist and Cubist influences. The Hagenbund movement reached its heyday in the 1920s; however, the seizure of power by National Socialists led to the dissolution of Austria’s leading artists’ association in 1938.

Ludwig Wittgenstein at the Leopold Museum

Instead of exploring the ground-breaking philosophical ideas of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889 — 1951) or his Logical-Philosophical Treatise published in 1921, the Leopold focused on his photographic work, displaying the family portraits he collected of his siblings (Helene and Hermine, shown below, and Margaret) for the exhibition entitled “Ludwig Wittgenstein: Photography as Analytical Practice” which was presented from November 2021 through March 2022.

Karl Wittgenstein, steel industrialist & patron of the arts during the Vienna Secession, fathered nine children — including the pianist Paul, the philosopher Ludwig, and Margaret, Special Representative of the U.S. Relief Program for Austria following WWI. The family lived in the Palais Wittgenstein (above), a palace later occupied by Nazis. For her wedding in 1905, Margaret was the subject of a famous portrait (below right) by Gustav Klimt {now in Munich’s Neue Pinakothek}. While working as a psychotherapy adviser in juvenile prisons, Margaret met Sigmund Freud and (over two years) was analyzed by him; they remained in contact until Freud’s death.

Vienna’s Leopold Museum

If you are interested in discovering more about “the prince of painters” Gustav Klimt, his “gifted disciple” Egon Schiele, and other Austrian painters, you may decide to check out our article “Klimt + Gold = The Belvedere — 4th Greatest Museum in Vienna.” Thank you for visiting our website, and reading about the Leopold Museum.

2 Comments

Walt

Excellent, and purely fun article about the Leopold. Interspersing photos of paintings throughout the narrative is so smart – I felt like I was visiting the museum in the moment. I spent a lot of time on a bench examining the very large “Life and Death” when I was there. It’s an extraordinary work. But my favorite is Schiele – your descriptions of the artists and movements are interesting and informative. Very good article.

HUMBERTO O CHÁVEZ

Dear Steven and Arthur, and the IT team

Thank you for sharing this with me. it’s a very impressive article. The text and photograps from the Leopold Musuem are inspiring.

Good memories.

Humberto O. Chavez.