Monet’s Gift Is Now the l’Orangerie + Matisse, Hockney & Modigliani

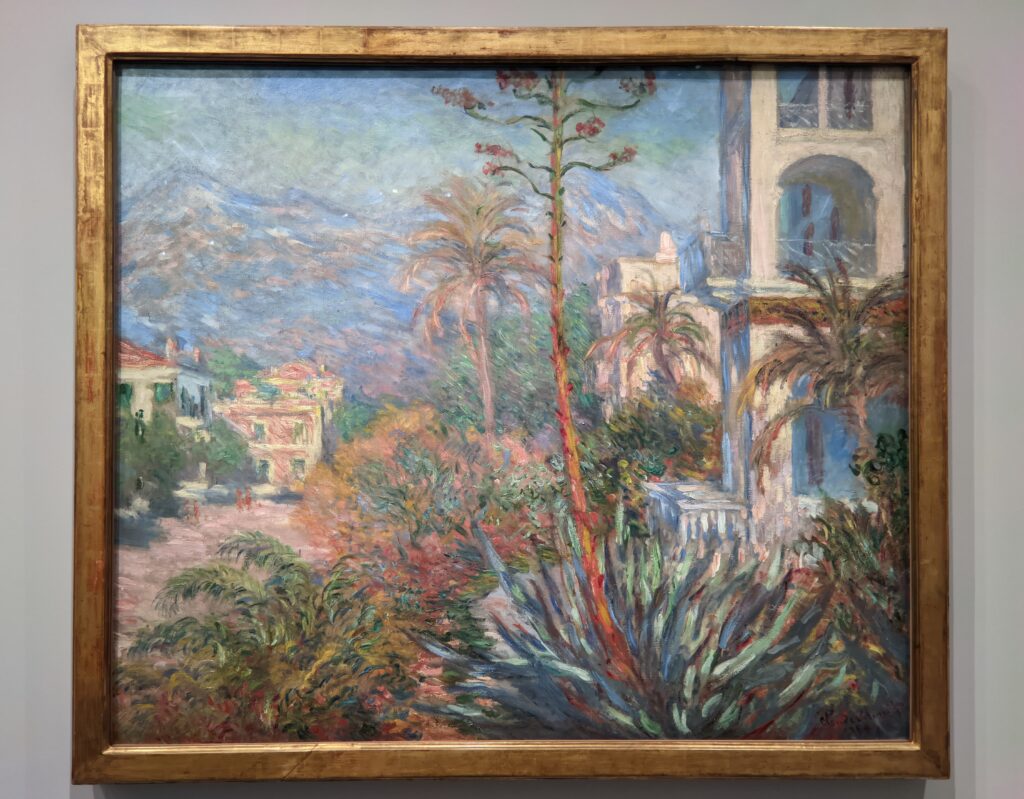

The Musée National de l’Orangerie des Tuileries in Paris is housed in a relatively small building, and yet it is brimming with joie de vivre — an exuberant enjoyment and celebration of life! Originally constructed to house citrus trees during the cold winter of 1852, the l’Orangerie truly blossomed in the 1920s when the French State and Claude Monet transformed the structure into a center for displaying fine art. For such a modest museum, the l’Orangerie offers a good permanent collection with Renoirs and Picassos, a dedicated exhibition space for temporary shows of the highest quality, and two spectacular oval rooms offering a peaceful and meditative setting for Monet’s water lilies.

The l’Orangerie Museum is blessed with a perfect location: on the right bank of the River Seine in the west corner of the Tuileries Garden, next to the Place de la Concorde, and within a 10-minute walk to the two greatest Parisian museums — the Louvre and the d’Orsay. The Jardin des Tuileries was created by Catherine de’ Medici in 1564, then opened to the public in 1667.

The Tuileries Garden became a public park following the French Revolution and today it is both elegant and relaxing — a perfect space for strolling (or jogging) in the center of Paris.

Monet’s Gift

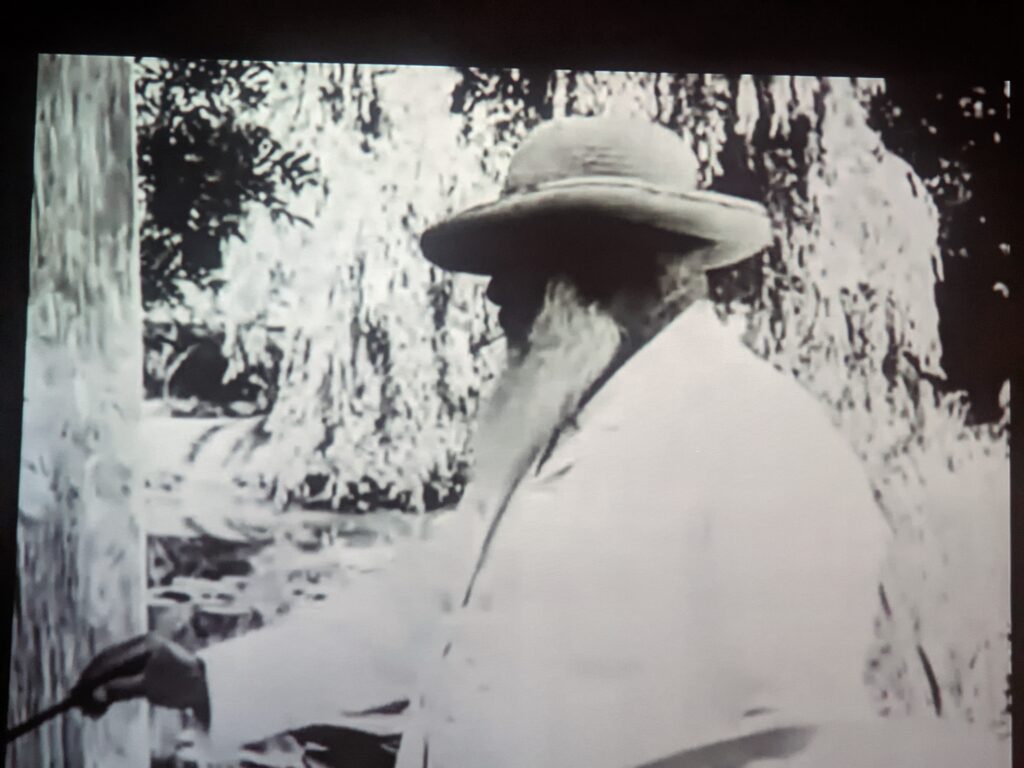

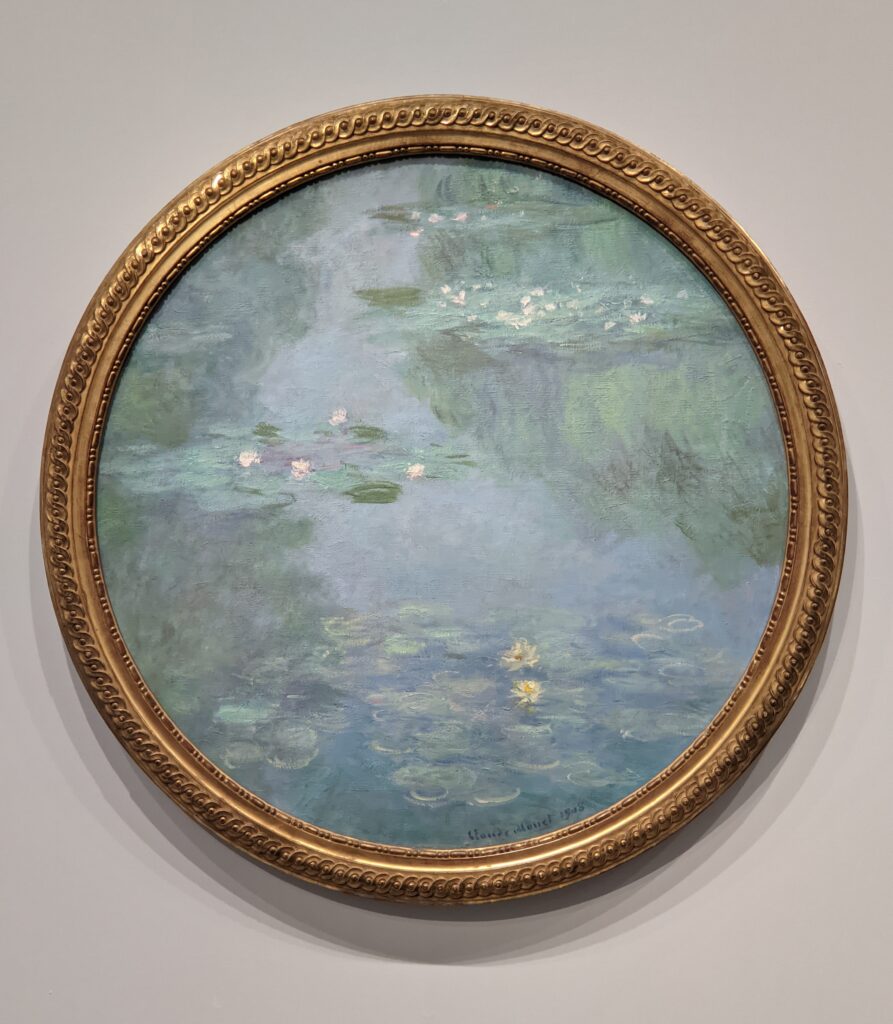

In 1921, Claude Monet was working on a series of water lily paintings entitled “Nymphéas” intended for the Rodin Museum. The plan was changed, the l’Orangerie was selected as the new destination, and Monet assisted in the design of these two rooms, lit by natural light.

“Nymphéas” became Claude Monet’s gift to the city of Paris: two oval rooms containing eight panels of water lilies measuring nearly 300 feet in length — 91 meters long — details of which are shown in these photos.

The Permanent Collection of the l’Orangerie

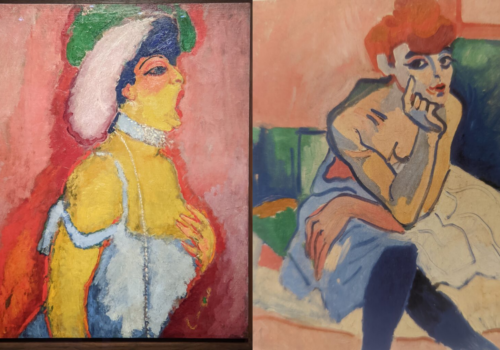

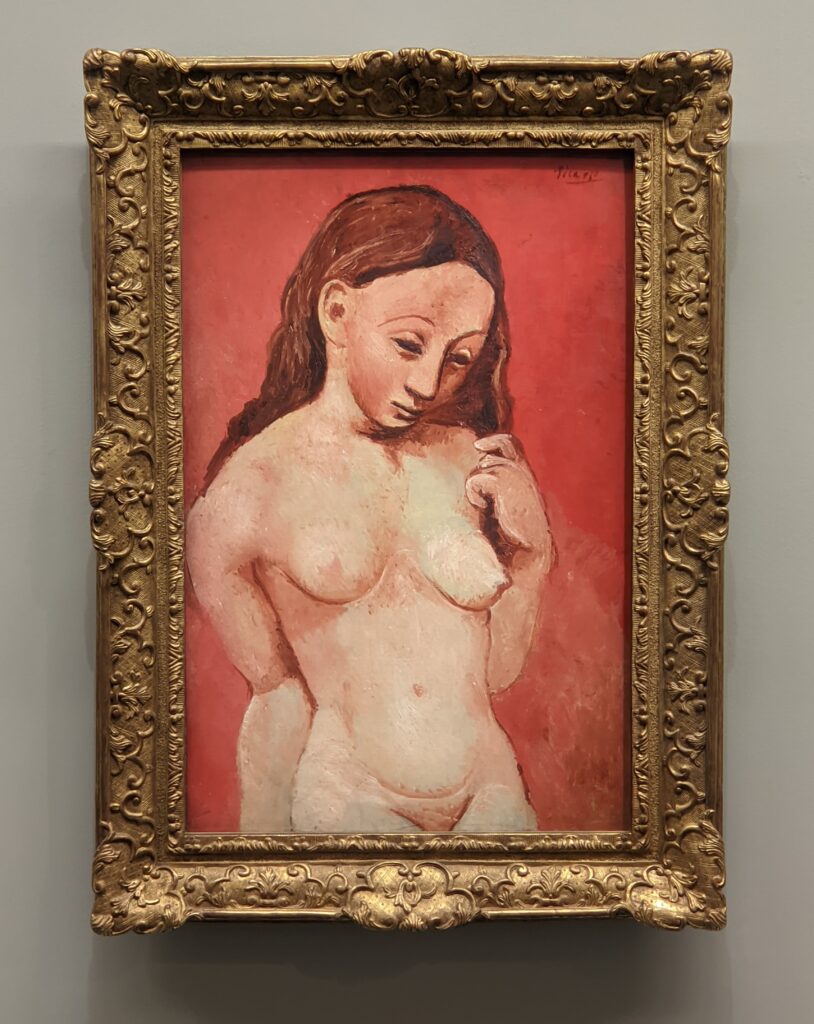

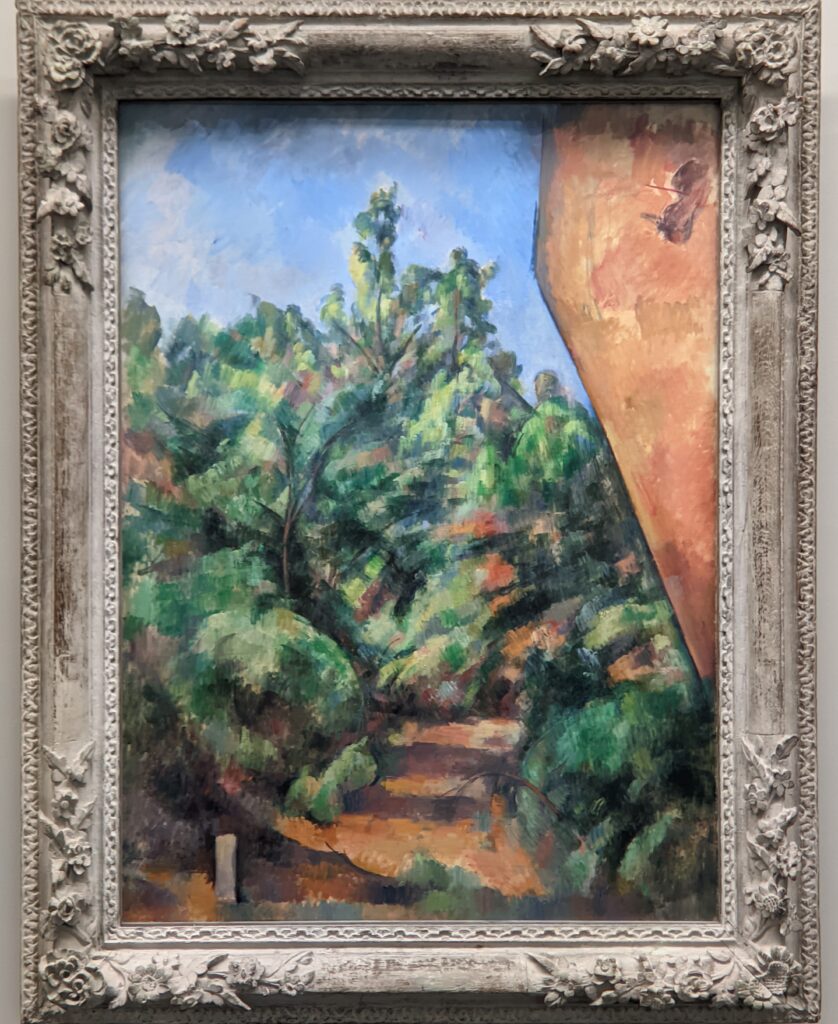

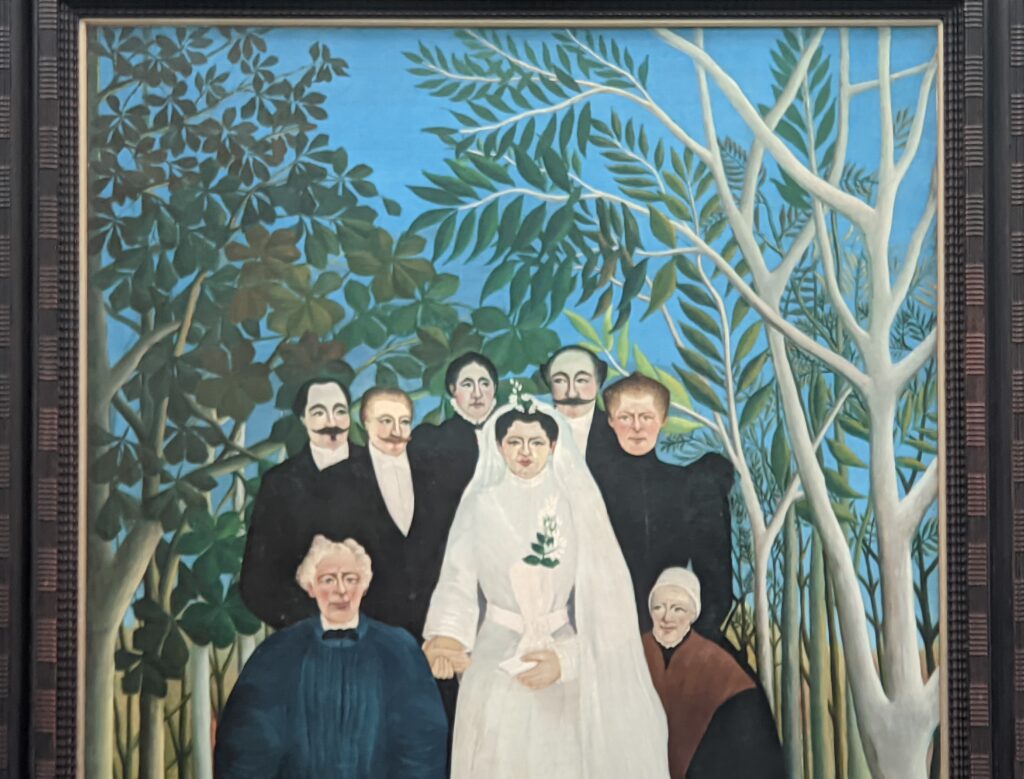

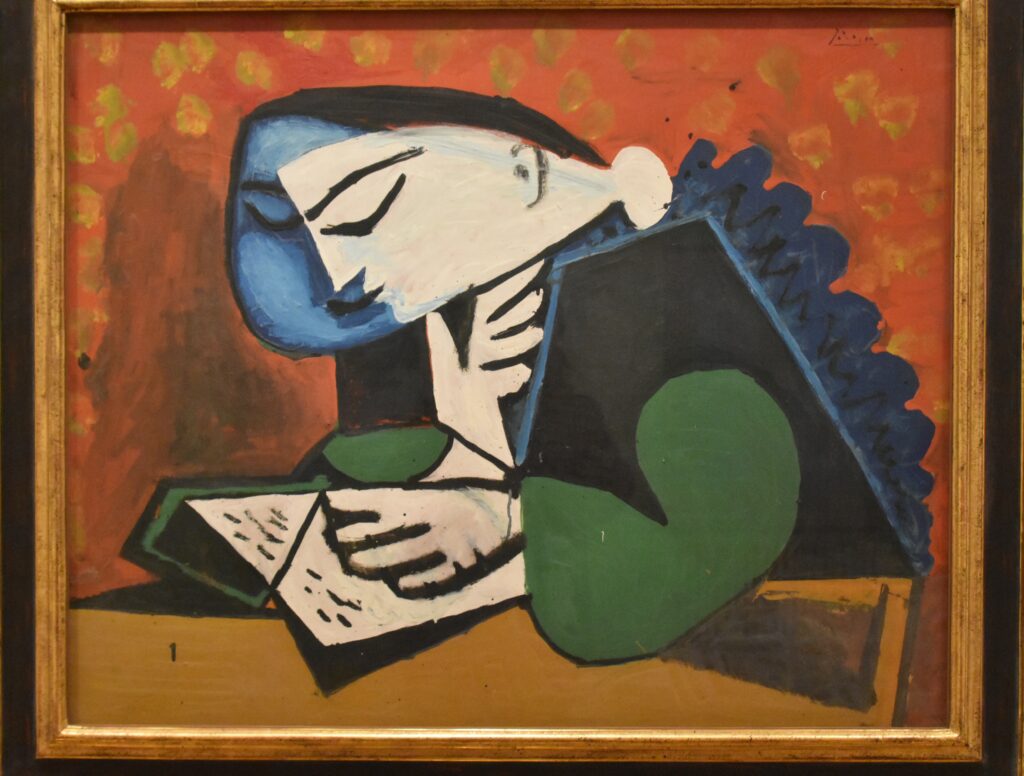

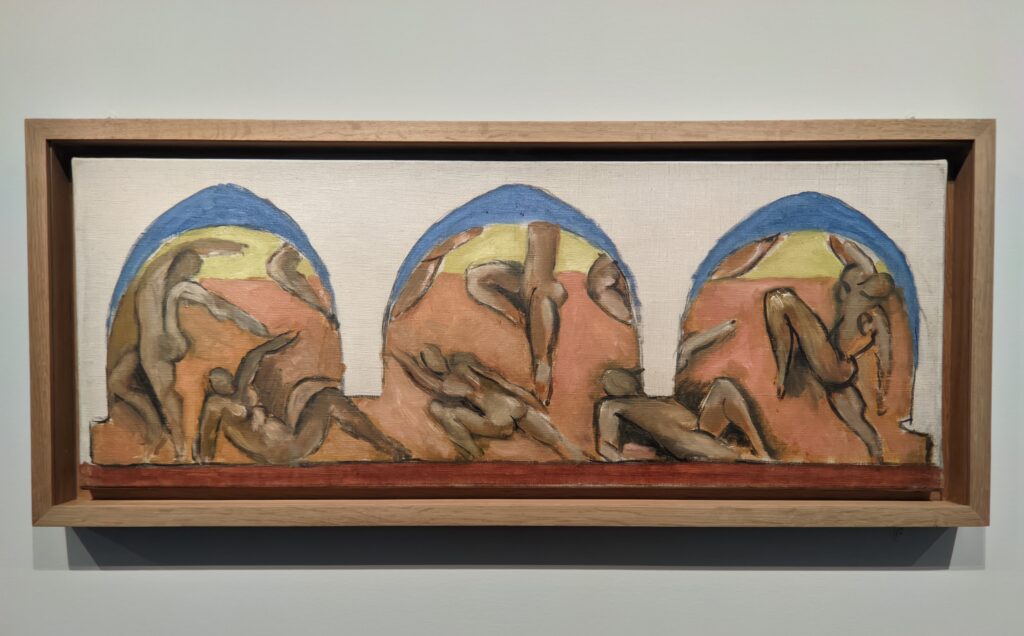

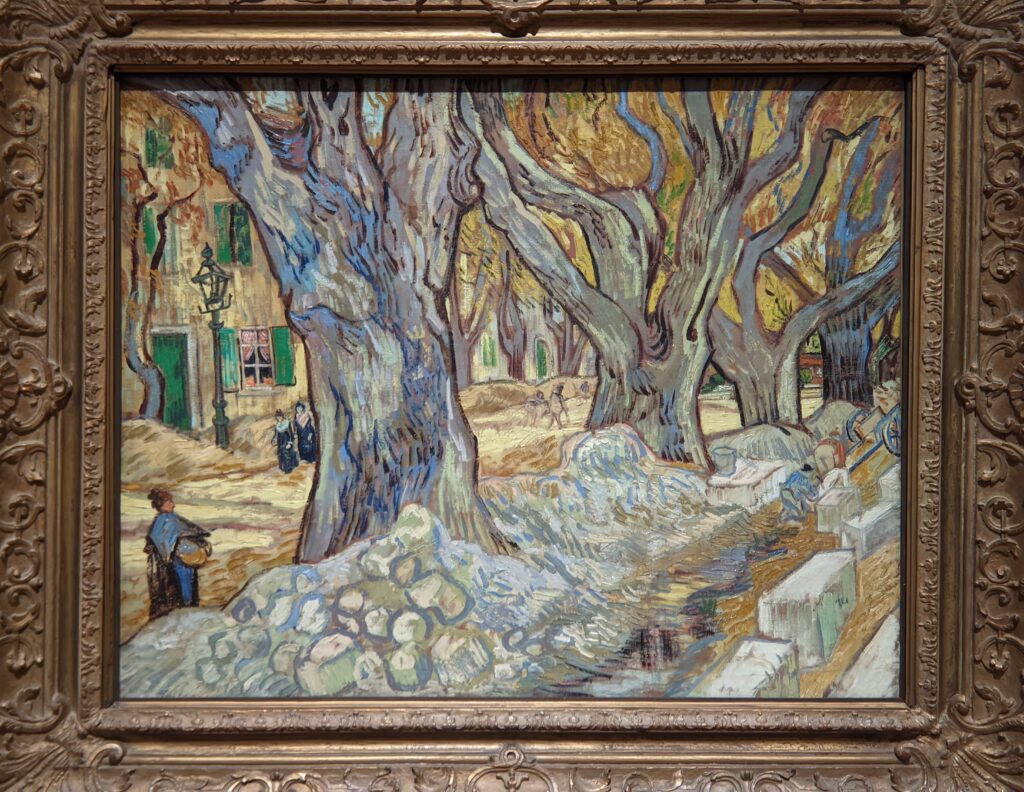

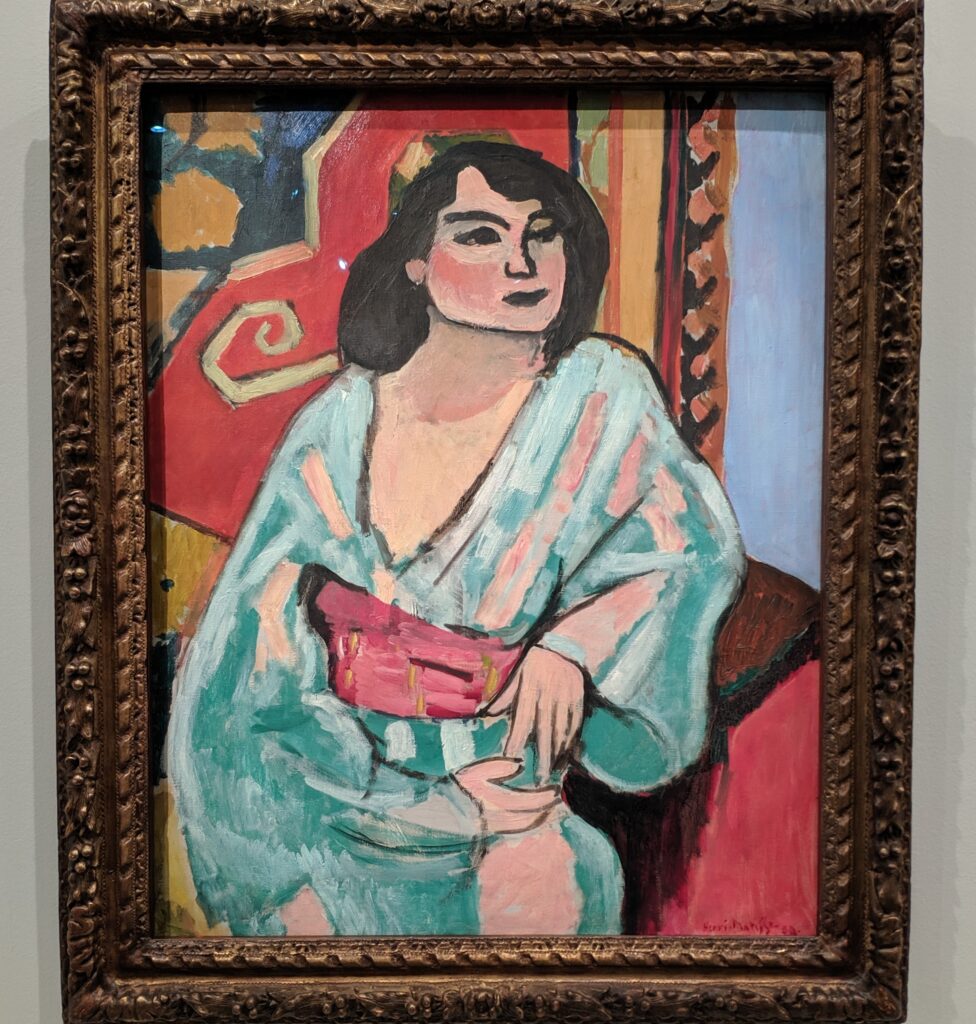

In addition to Picasso, Renoir and Cézanne, the following artists are well represented in the collection of the l’Orangerie: Laurencin, Rousseau, Soutine, Derain, Utrillo, Matisse and Modigliani.

Special Exhibits at the l’Orangerie

Through January 27, 2025, the l’Orangerie is presenting “Heinz Berggruen, a Dealer and His Collection,” featuring masterpieces by Klee, Giacometti, Matisse and Picasso. This special exhibition brings to Paris more than 100 paintings of exceptional quality from the Museum Berggruen/Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, and explores the personal taste and choices made by Heinz Berggruen, a major Parisian art dealer-turned-collector who favored the styles of Klee and Picasso.

Berggruen (born in a residential district of Berlin in 1914) fled from Germany to the USA in 1936, settled in Paris after World War II, and sold his collection to the German state in 2000, several years before his death in 2007.

Previous Exhibitions

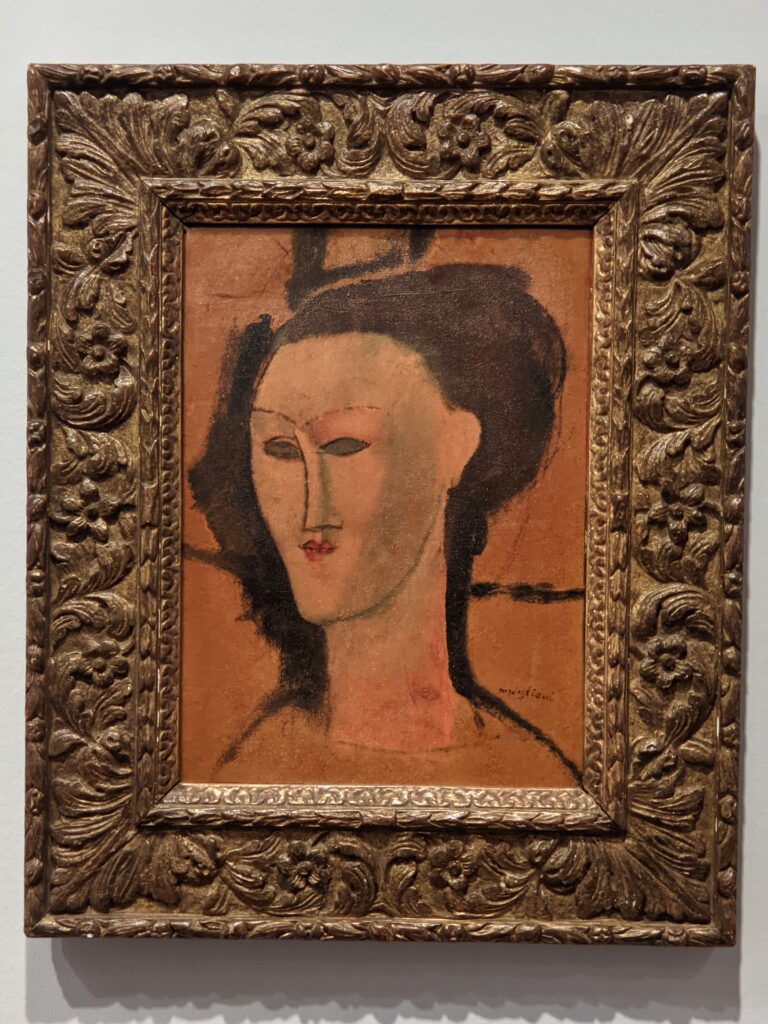

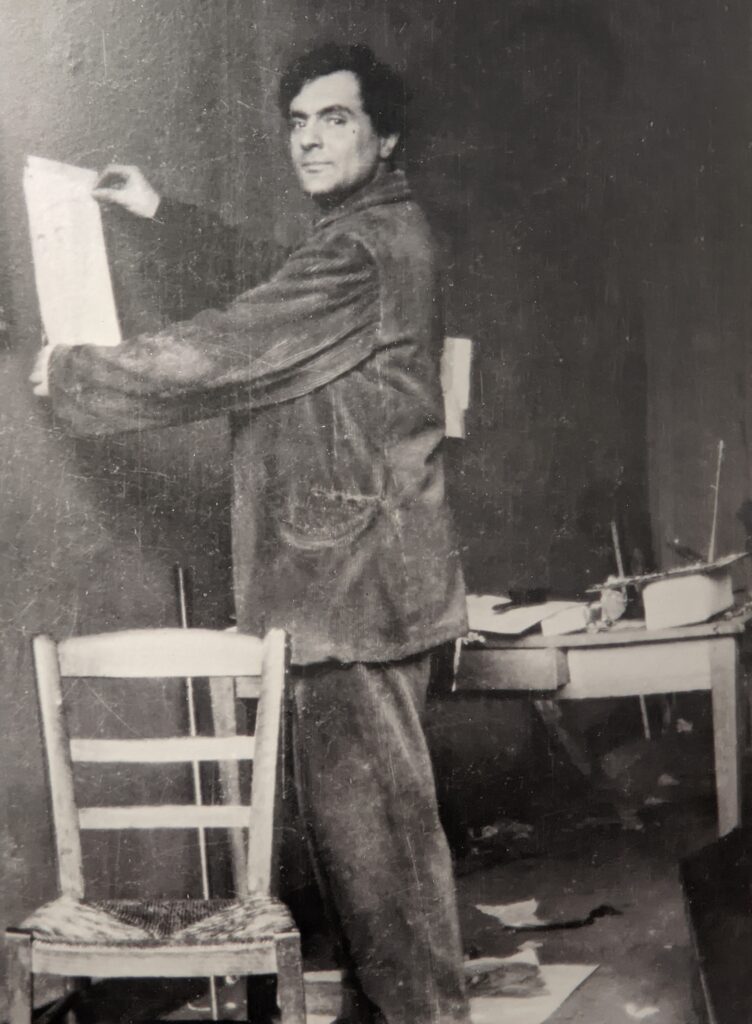

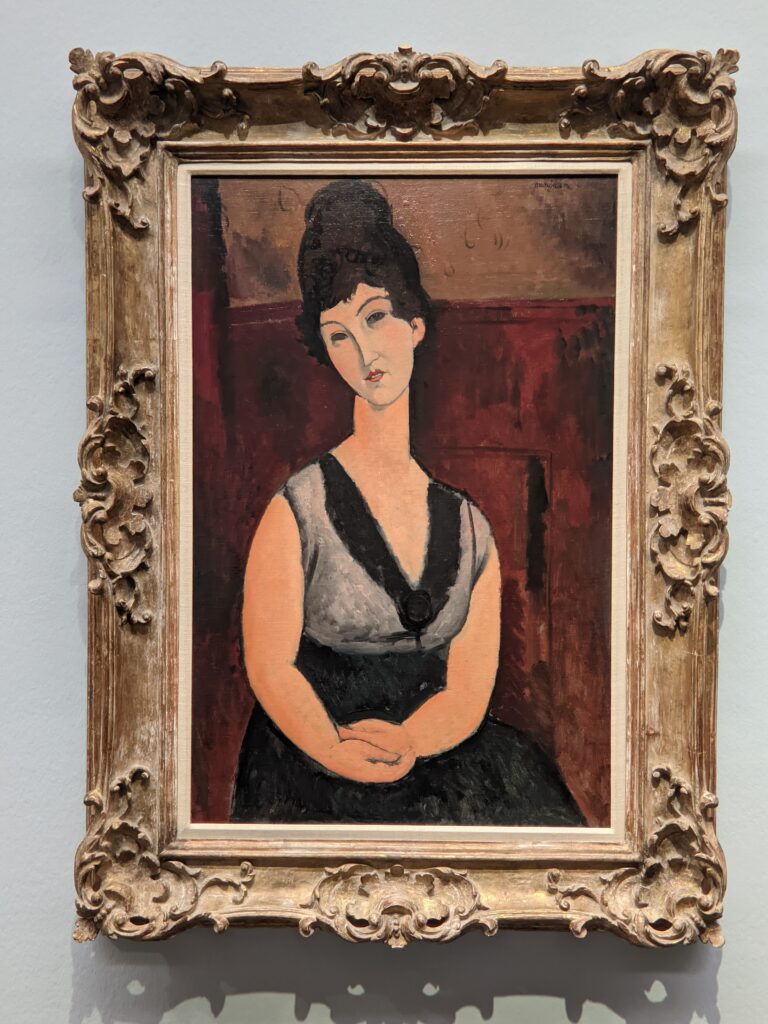

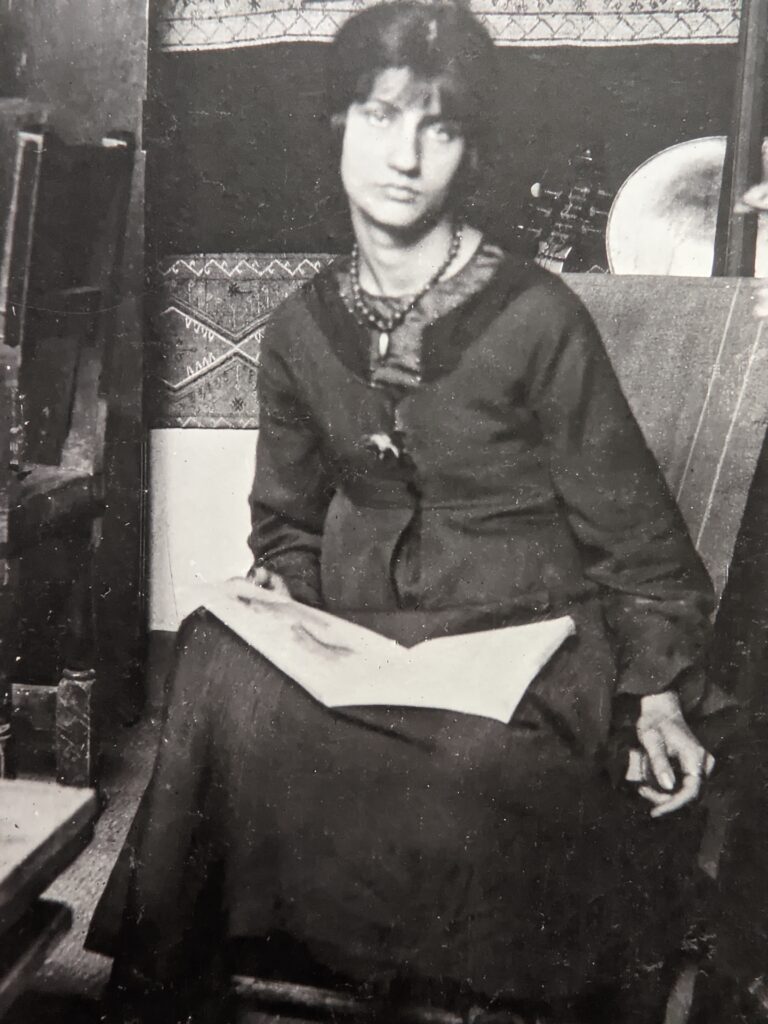

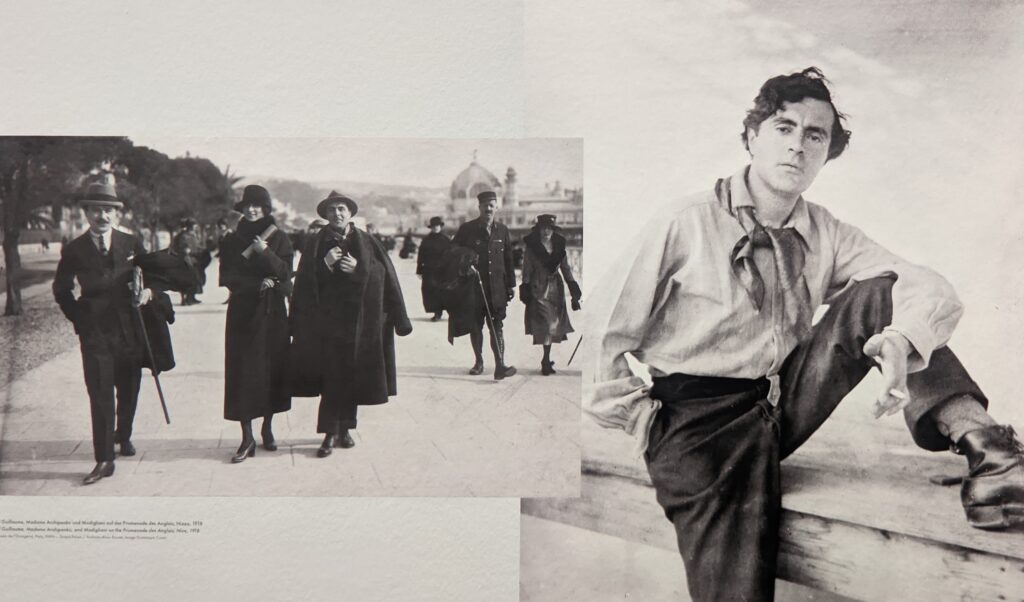

Paintings by Amedeo Modigliani were the subject of a special exhibition on view in the 2023-2024 season.

Entitled “Modigliani: A Painter and His Dealer,” this show explored the friendship between the artist and Paul Guillaume, as well as their mutual interest in fine art from Africa. Many painters from the School of Paris, including the most modern artists such as Matisse and Picasso, would visit the Ethnographic Museum of Trocadéro (pictured below, beyond the Eiffel Tower) to gain inspiration from African art.

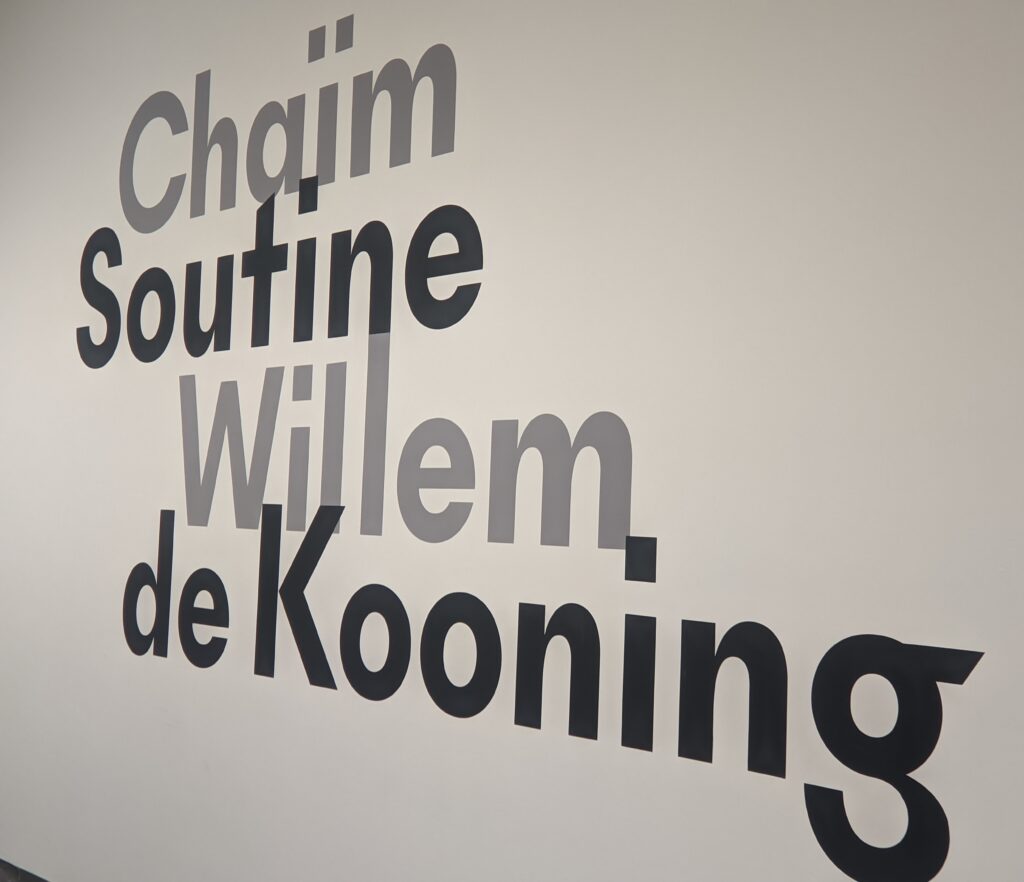

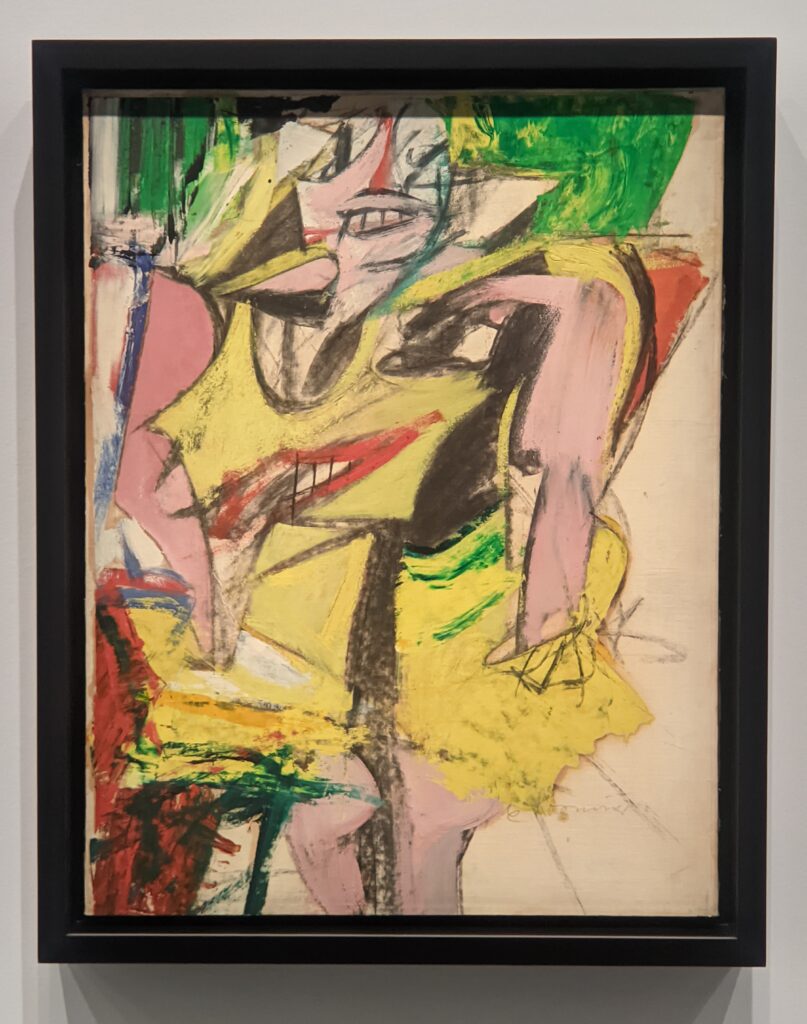

The Russian Chaïm Soutine (1893-1943) was one of the painters of the School of Paris. His canvases are characterized by a thick impasto and the gestural qualities of his portraiture. The curators at the l’Orangerie paired Soutine with an important artist from the next generation: the Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning (1904-97), whose unique figurative painting was much closer to abstraction.

The American collector Albert Barnes boosted the international reputation of Soutine by purchasing dozens of his paintings during a single trip to Paris in 1922. De Kooning attended the Soutine retrospective at MoMA in 1950 and then visited the Barnes collection outside Philadelphia in 1952. This exhibition presented a visual dialog between these two artists known for their energetic brushwork and the importance they placed on their painterly surfaces. This show was displayed at the Barnes Foundation in 2021 and closed at the l’Orangerie museum in January 2022.

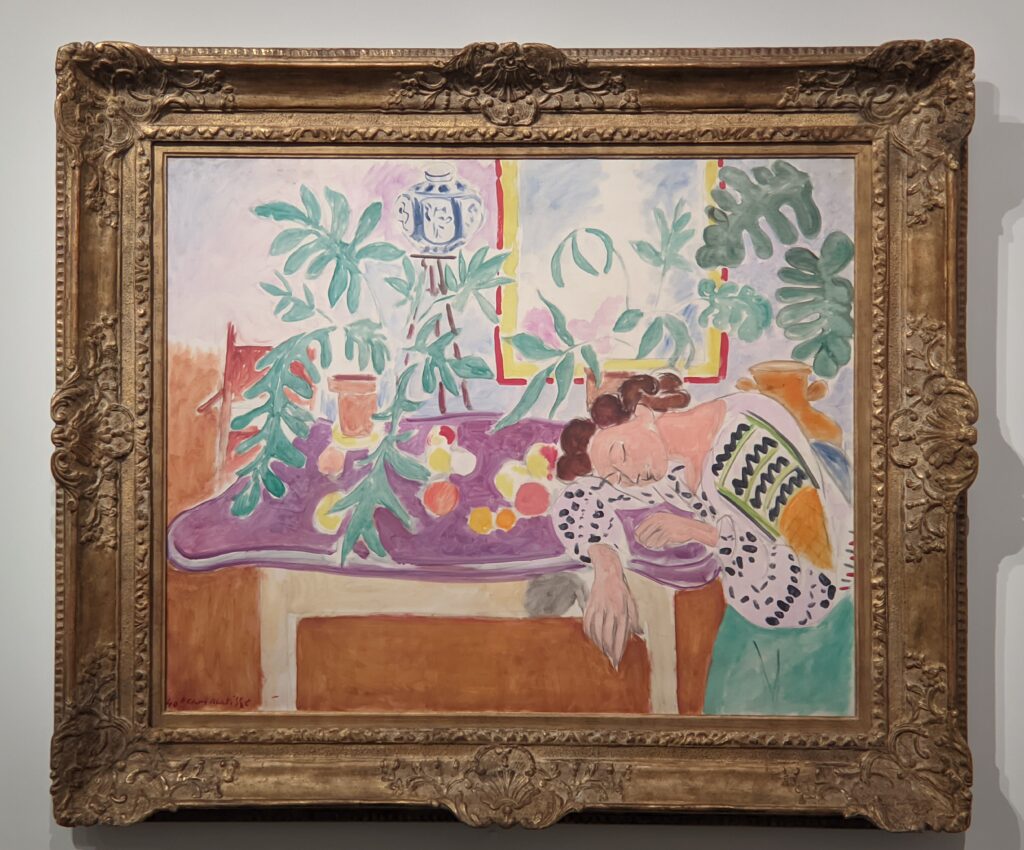

“Matisse — Art Books, the Pivotal 1930s” Was Presented in 2023

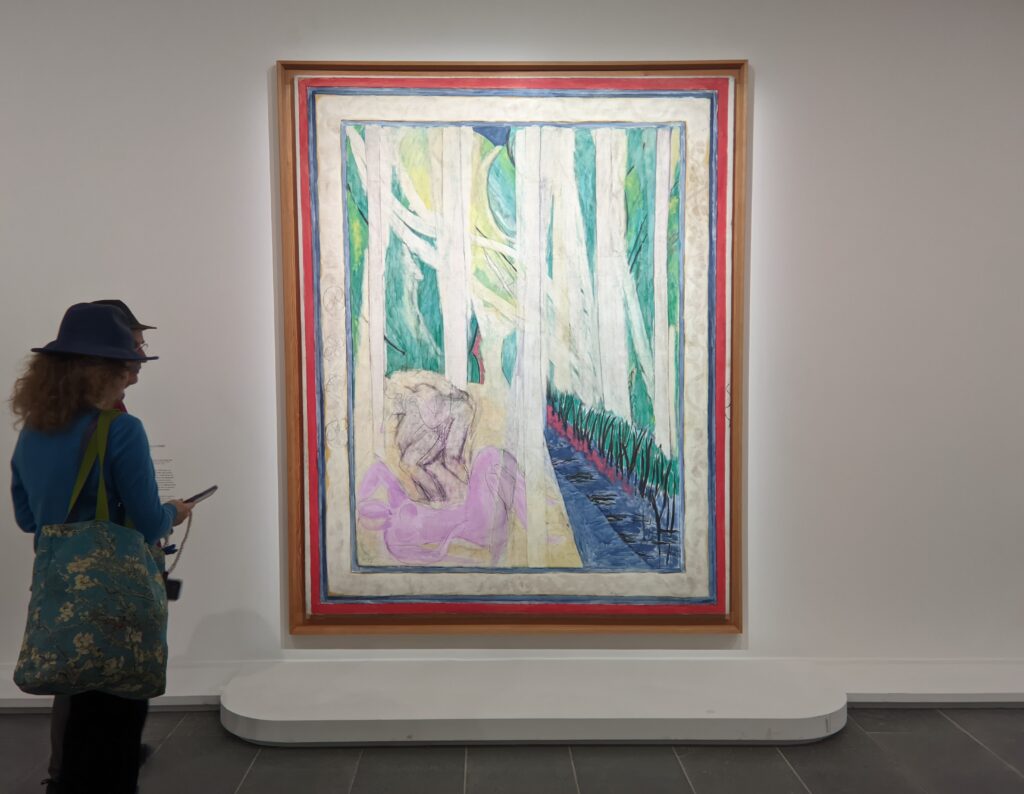

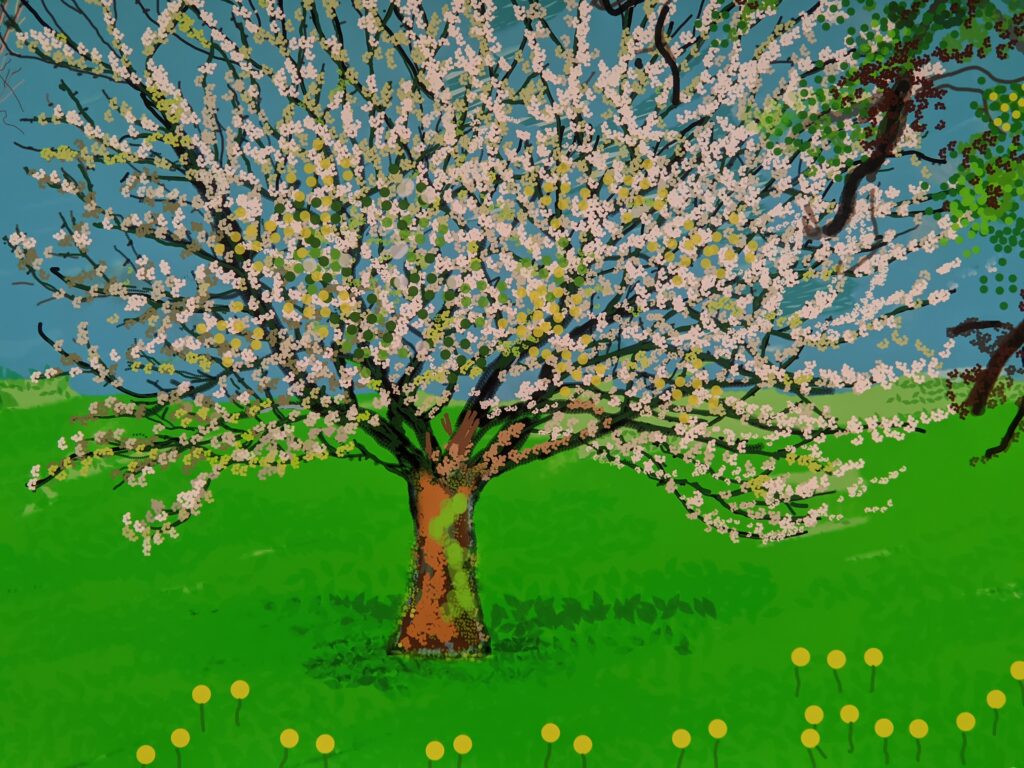

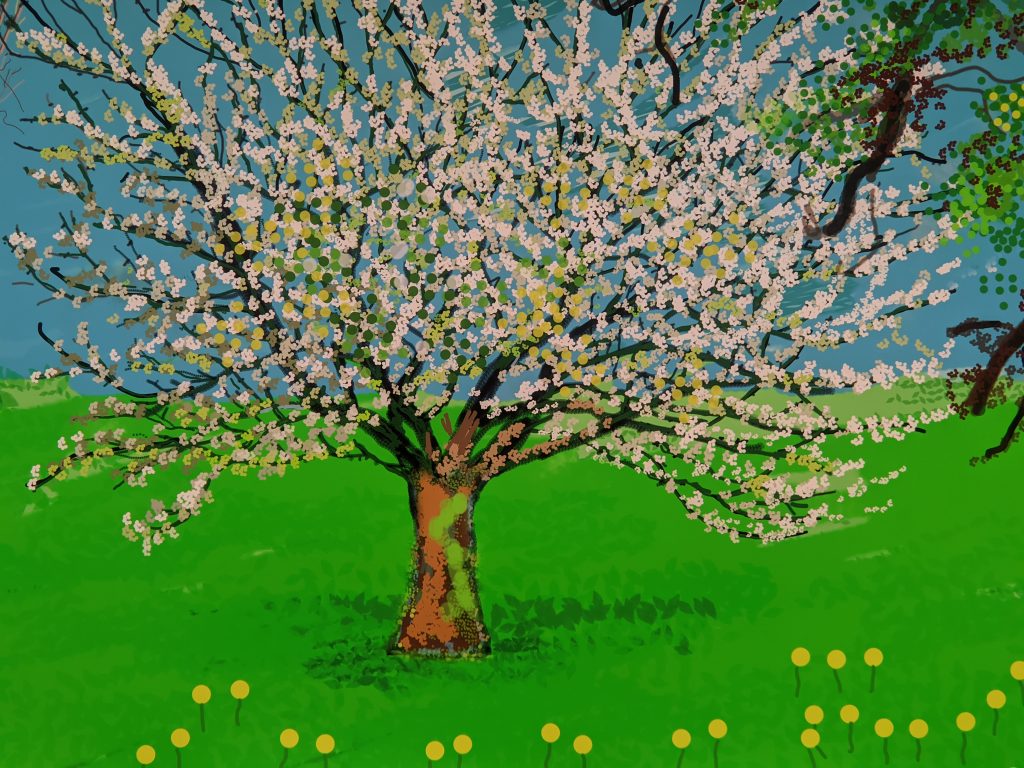

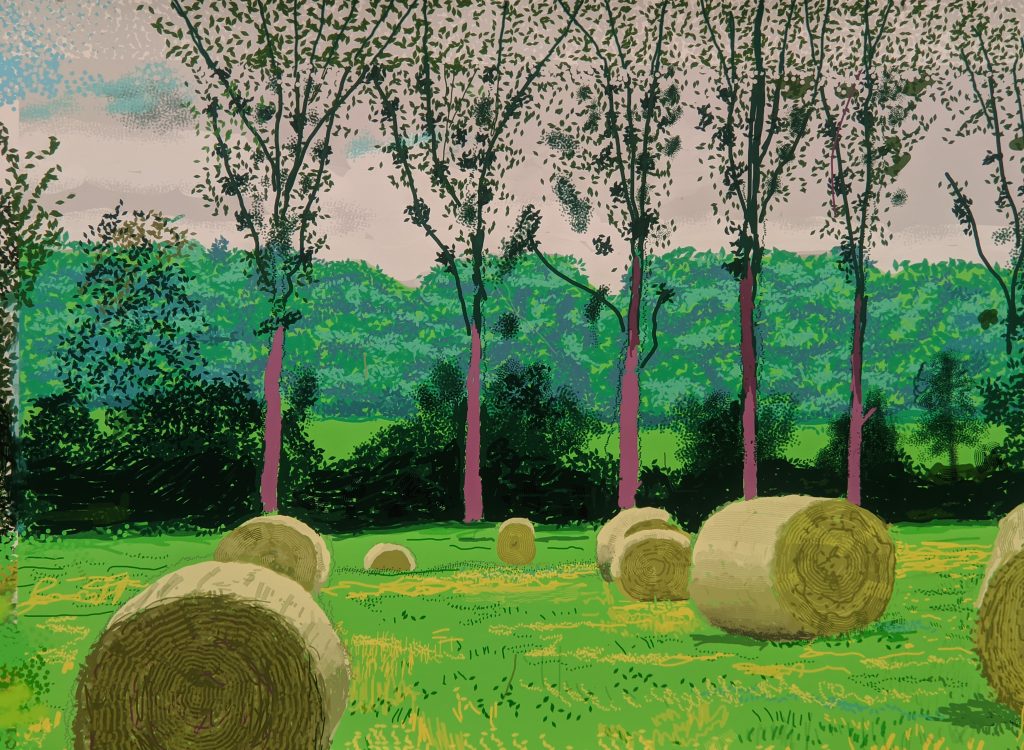

“David Hockney — A Year in Normandy”

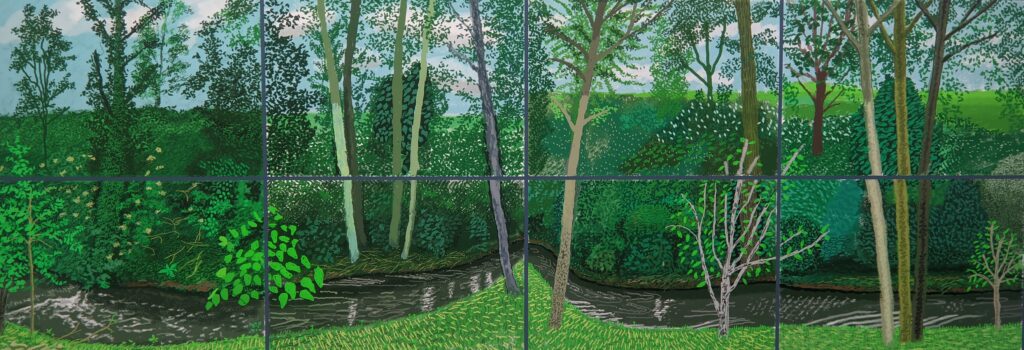

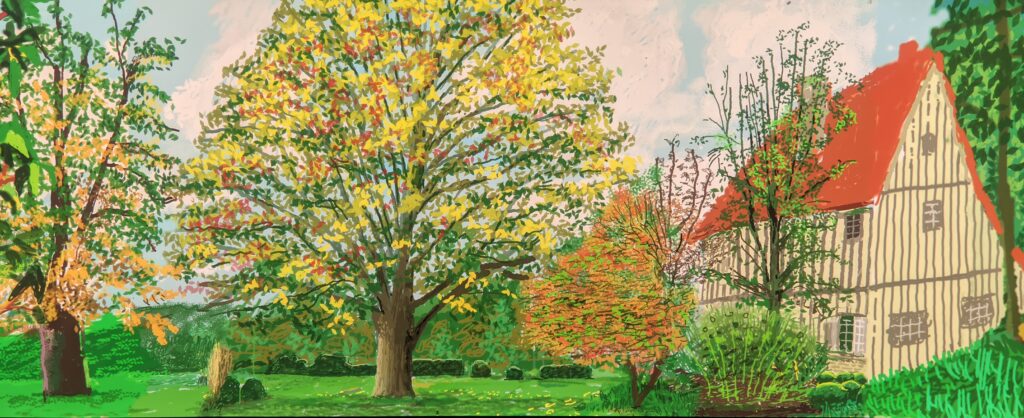

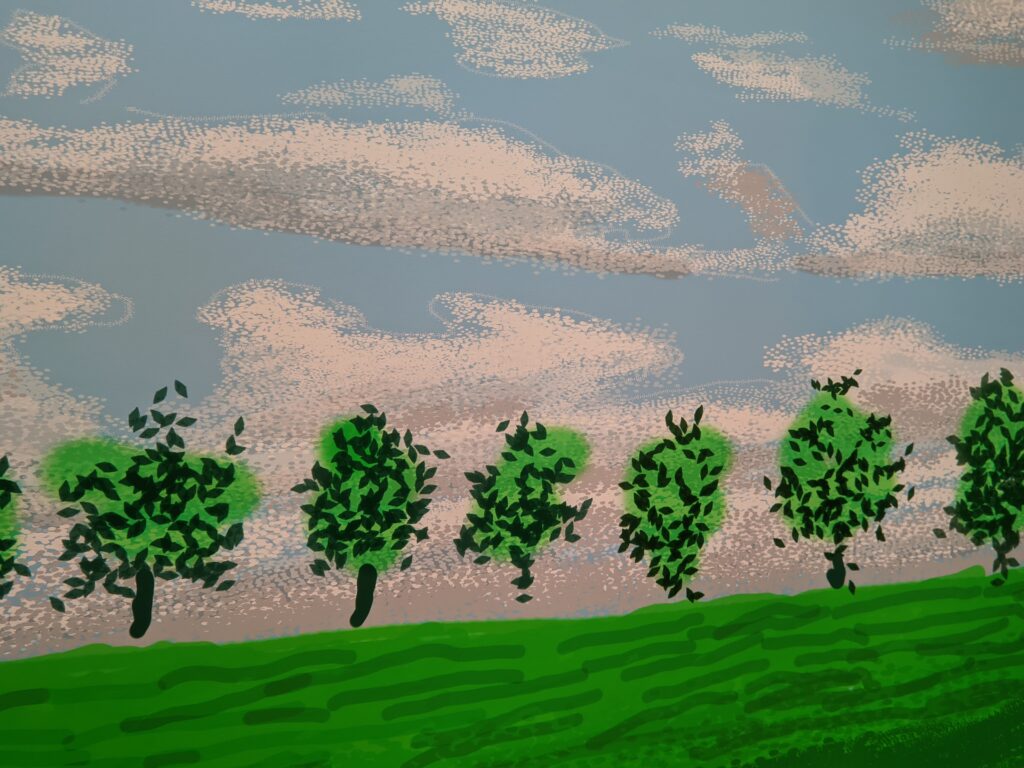

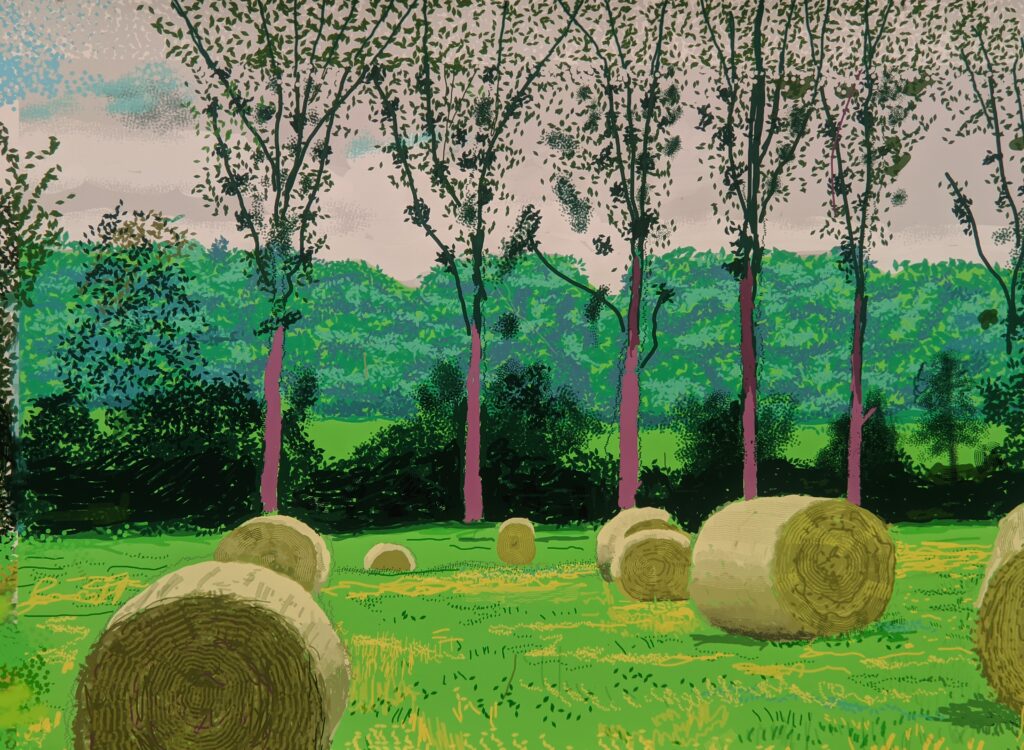

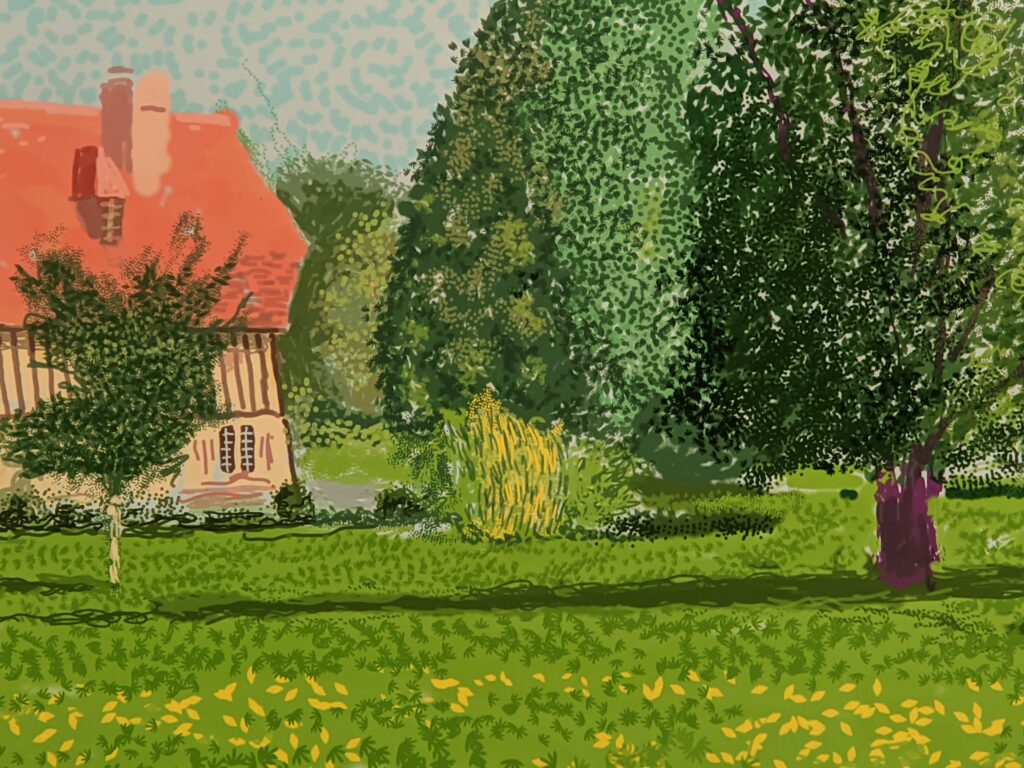

Images from the series The Arrival of Spring, 2020, were created in Normandy by David Hockney and are marked here with an asterisk (*)

In the 2021-2022 season, the l’Orangerie Museum showcased the iPad drawings created in 2020 by David Hockney at his home, garden and studio in the Normandy region of France. Even though Hockney had been using his iPad method of drawing for more than 10 years, Covid-19 pandemic restrictions were coming into vigorous effect as the months of spring 2020 were unfolding. For Hockney drawing provided an antidote to the anxiety of those days: “We need art, and I do think it can relieve stress,” he said. As winter passed and spring gradually arrived, Hockney recorded the transformation and blossoming of the bucolic setting that surrounds his studio in northern France — home to historic places such as the Gothic abbey on Mont-Saint-Michel, Rouen’s Notre-Dame Cathedral and the 11th-century tapestry at Bayeux 10 kilometers from the Channel coast.

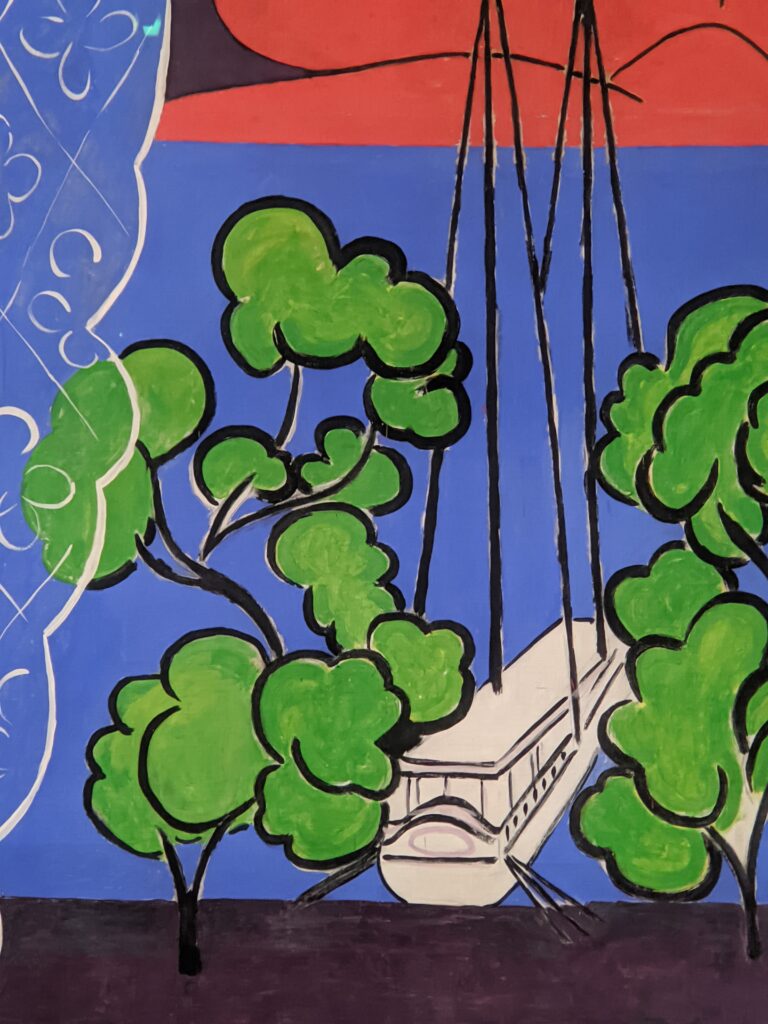

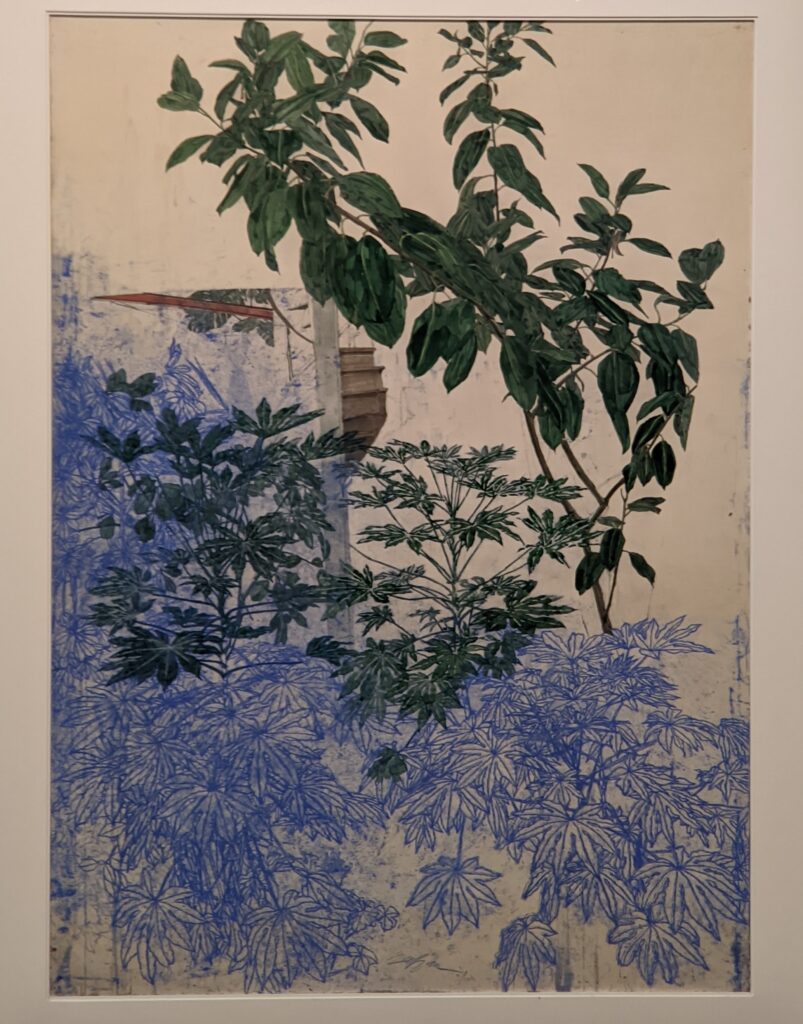

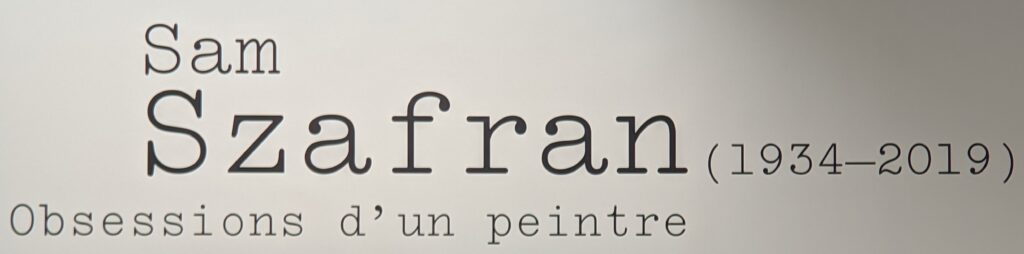

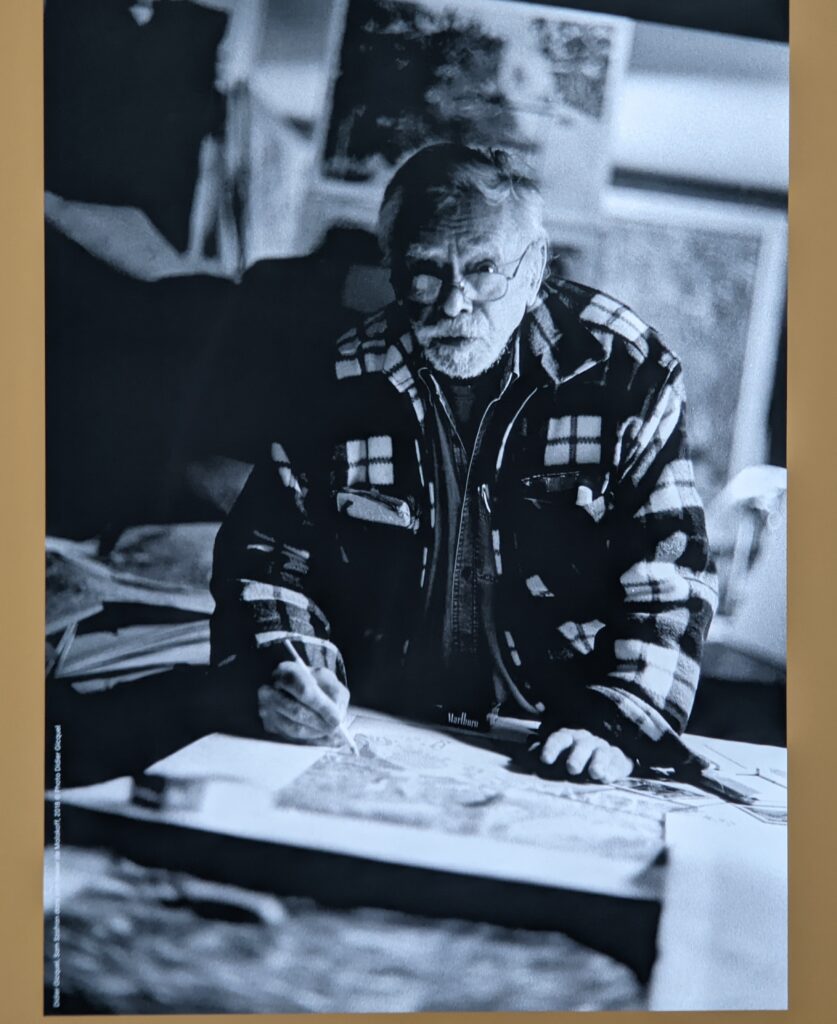

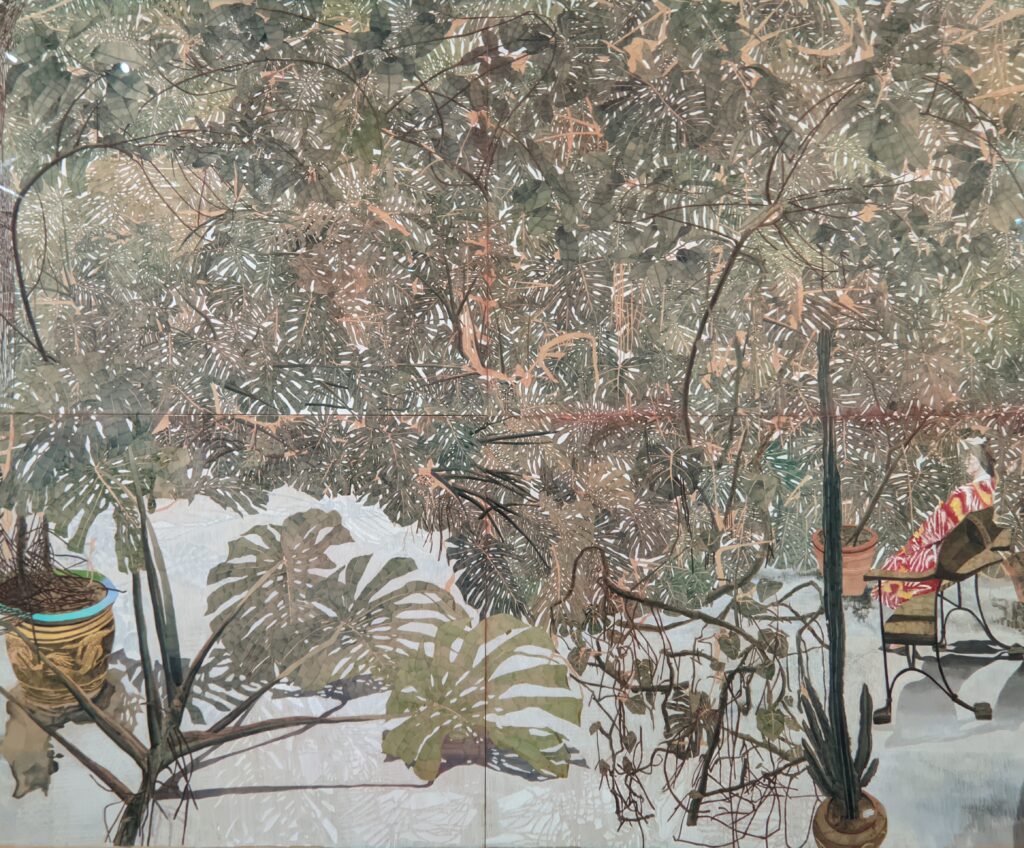

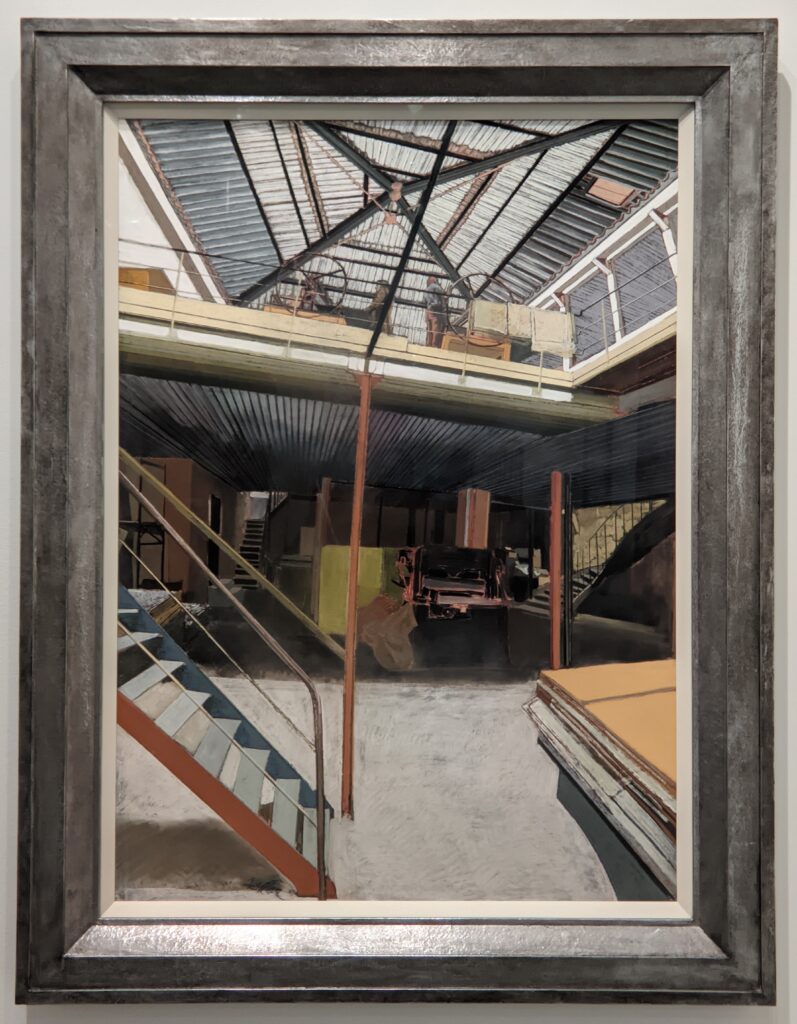

Sam Szafran preferred to work in the seclusion of his studio, far removed from the big-city and international art scenes. As a self-taught artist, Szafran introduced himself to pastels before exploring watercolors. Szafran’s methodical application of these mediums combined with his distorted perspective invite the viewer into his labyrinthine, challenging and at times claustrophobic world. For large-scale works of art, he turned primarily to his watercolors, though he often mixed dry with wet on paper using his two favorite materials — pastel and watercolor — which is no easy task to master. In the isolation of the workshop, Szafran depicted and deconstructed the world around him, including the plants in his art studio. Throughout his life, he returned to these ornamental foliage motifs in what he called his “nod to Matisse.” This show closed in January 2023.

The son of Polish Jewish immigrants, Sam Szafran (1934 — 2019) was born in Paris. His childhood was scarred during World War II when he was hidden in the French countryside and Switzerland before being reunited with his mother in 1944. “From the age of 7, I lost my innocence,” he said. “I was hunted like an animal by the Germans. It has never left me.” Szafran was captured by the Nazis, sent to an internment camp, and barely escaped deportation to a death camp. He was freed by U.S. troops. Szafran’s father, a tailor, died in Auschwitz.

Even as a child Szafran understood that he wanted to be an artist. Later in life, he preferred the solitude of his immediate creative environment, focusing on his favored themes: staircases, plants, and the artist’s workshop. The curators at the l’Orangerie rightly pointed out that Szafran’s fascinating body of work “occupies a very singular place in the history of art in the second half of the 20th century.”

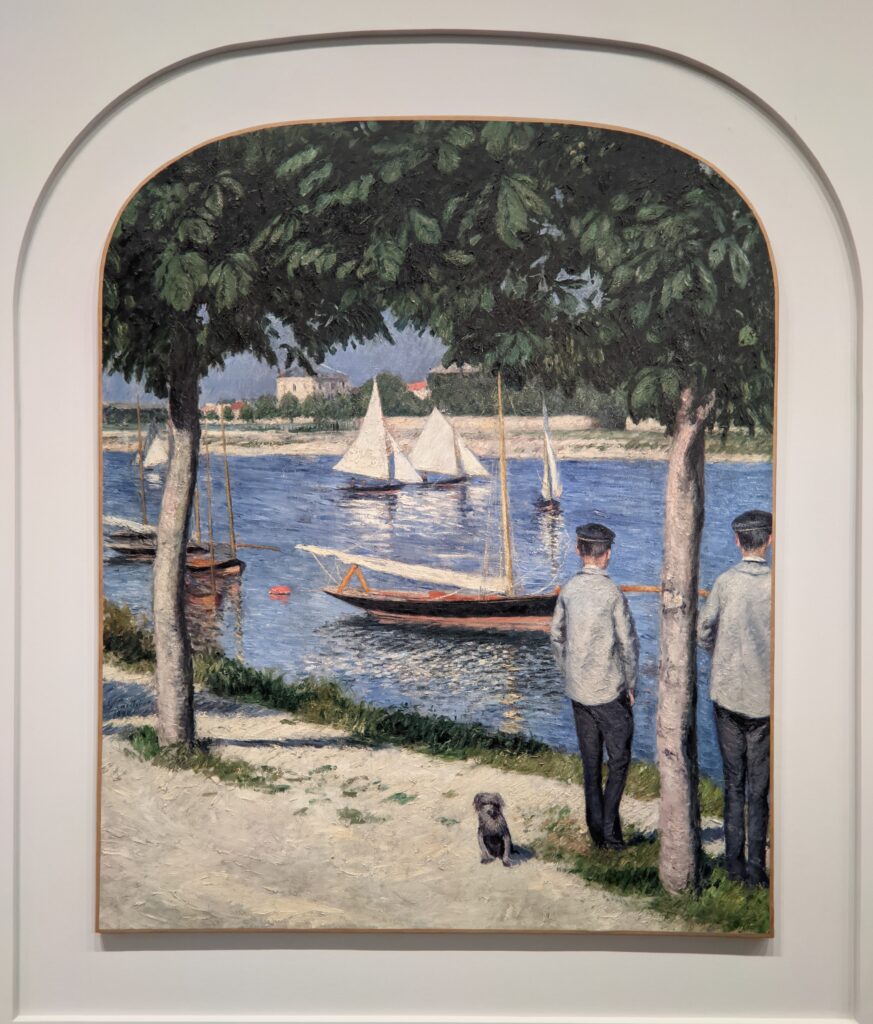

“Félix Fénéon — The Modern Times, from Seurat to Matisse”

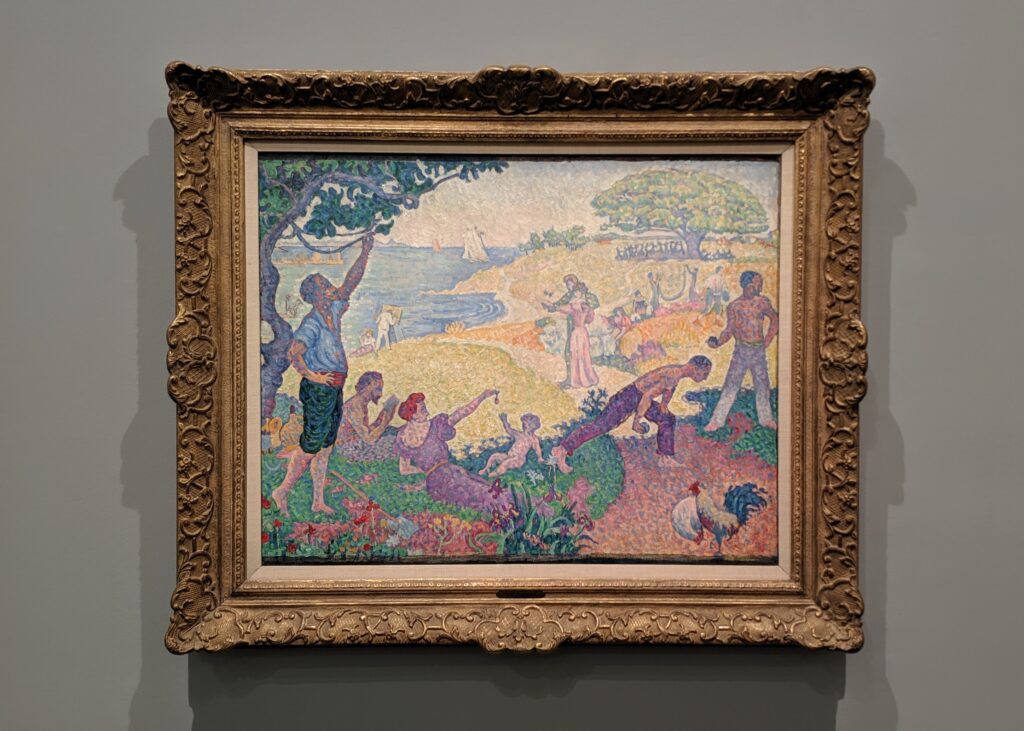

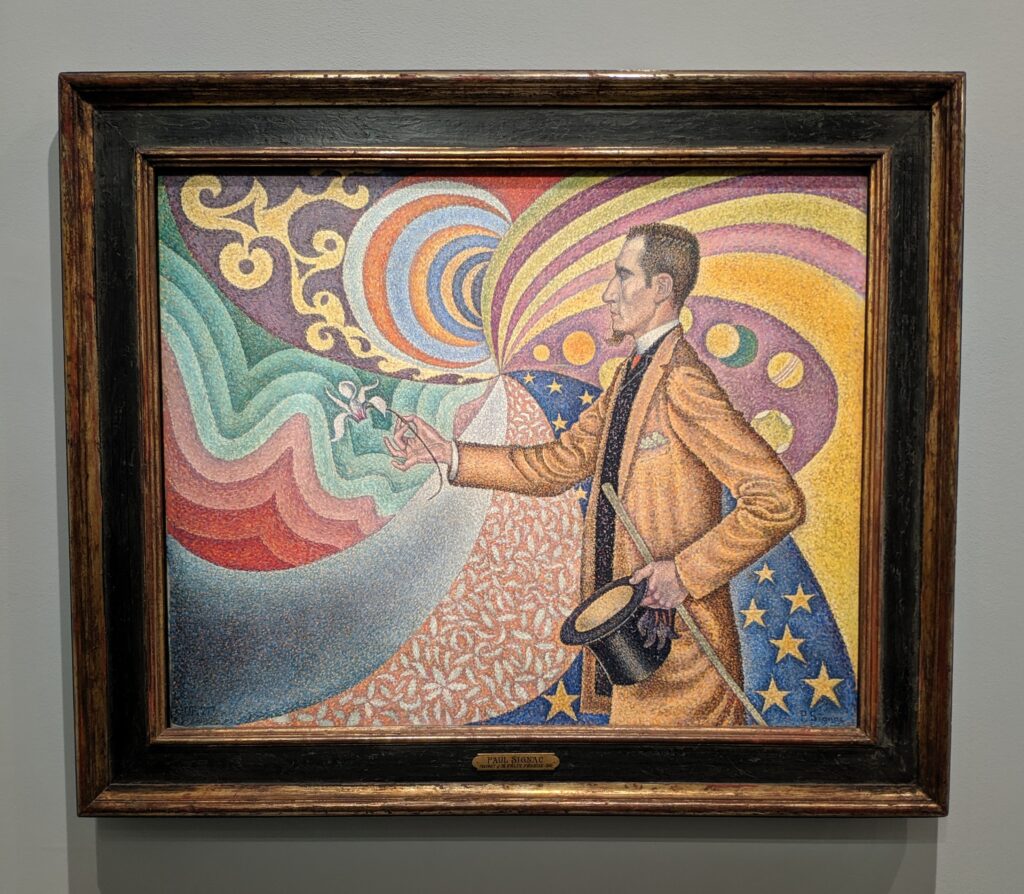

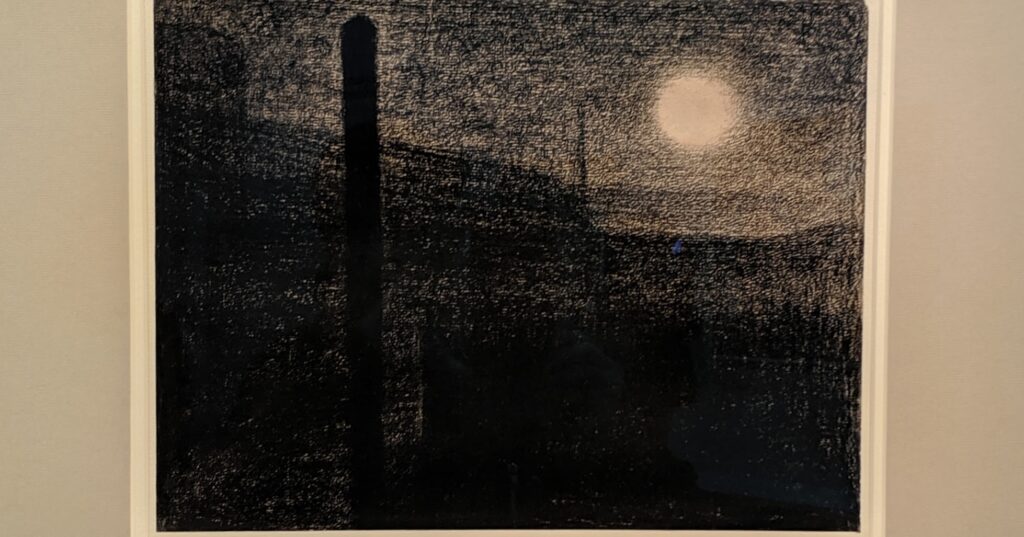

The l’Orangerie teamed up with the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York during the 2019-2020 season to explore the artists who were championed by Félix Fénéon, an influential art critic and anarchist. In his desire to help the underprivileged in society, Fénéon was known to be exceptionally generous. As a journalist and publisher, Fénéon coined the term “Neo-Impressionism” to describe the use of bright contrasting colors by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, as well as “pointillism” — the technique of using tiny dots of pure colors to create images. Fénéon’s commentary and financial support advanced the careers of these avant-garde Neo-Impressionists, and other artists such as Modigliani, Bonnard and Matisse. In his portrait of Fénéon(above), Signac was inspired by the pattern on a Japanese kimono to create the swirling fan of colors in the background in order to convey a sense of harmony. Fénéon thought he should be depicted frontally but Signac painted him in left profile, perhaps suggesting a new and enlightened way of envisioning the world with Fénéon and the artists he promoted leading the way. Isabelle Cahn, senior curator at the Musée d’Orsay, stated, “Bright colors are not realistic. They mean something higher than reality, and this higher reality is hope, is joy—it’s optimism. Bright colors helped to build a new world, a world of harmony, a world of abstraction from reality.”

Starr Figura, a curator in MoMA’s Department of Drawings and Prints, observed: “The climate that he lived in is amazingly relevant today. It was a world where there was a huge gulf between the economically advantaged and disadvantaged, the access to power, the glorious benefits of new technology, and the social structures that inhibited people from fully participating in them.”

“Impressionist Décor“

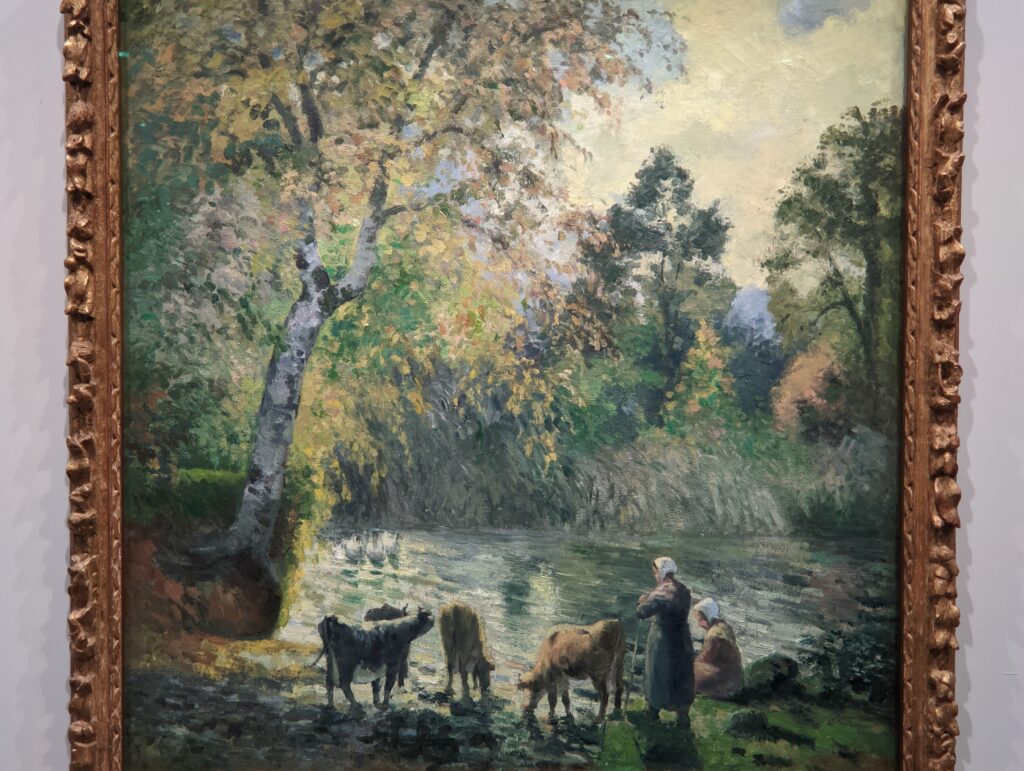

The exhibition “IMPRESSIONIST DÉCORATIONS: Tracing the Roots of Monet’s Waterlilies” was presented in 2022 on the l’Orangerie’s lower level. Painting landscapes outdoors, rendering luminous flowers on canvas, presenting scenes of modern life on rivers and farms, and posing female models in the latest fashions (including accessories like fans and umbrellas) appear to be, by today’s standards, tame artistic activities. In France during the 1870s and 1880s, however, focusing on such pursuits and subject matter was ground-breaking for artists such as Pissarro, Manet, Renoir, Monet, Caillebotte and Degas.

The famous poet, art critic and essayist Charles Baudelaire derisively called representations of flowers on canvas “dining-room paintings.” The Impressionists excelled at depictions of nature, well aware that such works of art were popular with their clients and patrons who wanted to create harmonious, decorative atmospheres within their homes. Monet even referred to his Water Lily series installed here as “grandes décorations.”

The Impressionists held eight exhibitions (independent from the State-sponsored Salon) between 1874 and 1886. The 4th Impressionist Exhibition (1879) included more than 20 fans — a fashion accessory (and tool of seduction) in vogue during the 2nd half of the 19th century in Europe, especially Spain, and Japan.

In 1890, Gustave Caillebotte painted “The River Bank at Petit-Gennevilliers and the Seine” (above) as a decorative piece for the apartment of his younger brother, Martial. Caillebotte and Claude Monet, both avid gardeners, were the best of friends. Shortly after Caillebotte’s death in 1894, Monet received a painting of chrysanthemums from Caillebotte; and Monet wrote the following words to describe his good friend: “If he had lived instead of dying prematurely, he would have enjoyed the same upturn in fortunes as we did, for he was full of talent.” In 1897, Monet paid tribute to Caillebotte by painting a thicket of chrysanthemums (below) composed of a sophisticated arrangement of colors, without a traditional sense of perspective.

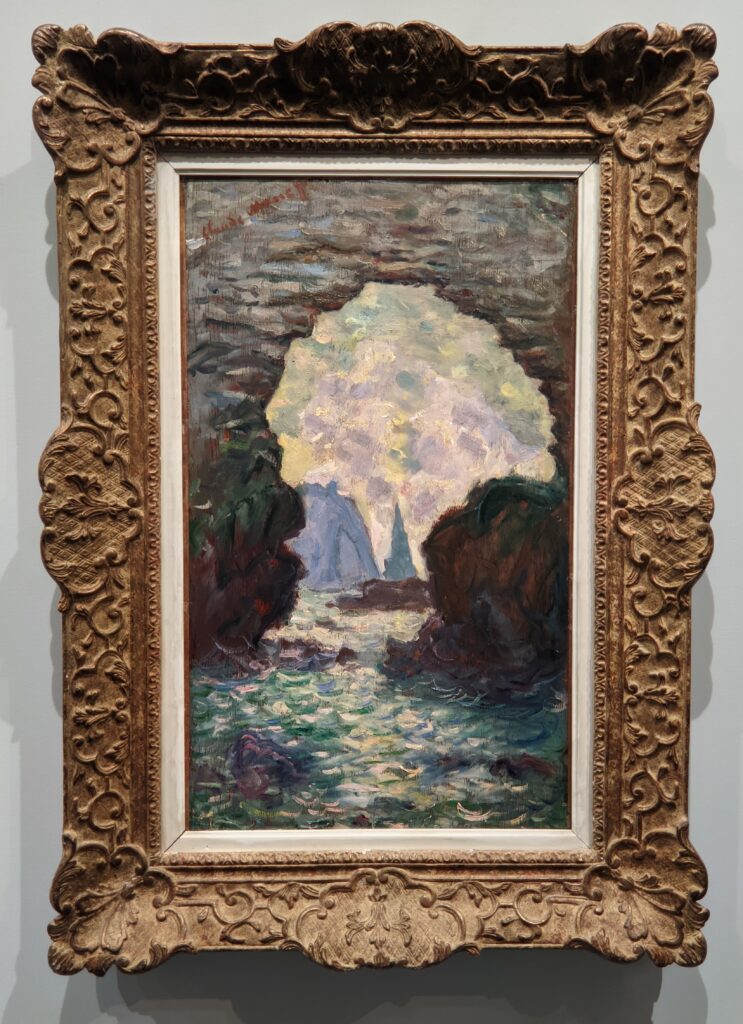

Claude Monet created two seascapes of the cliffs and rock formations at Étretat while staying at an inn in Normandy. These paintings were painted directly on inn furniture — in this case the doors of an armoire (above left) — as a form of decoration. The second seascape (below) was removed from the inn and placed in a new frame in the 20th century.

Even though the Impressionists sought independence by staging self-organized exhibitions of their creations, Pissarro, Monet and Renoir sought commissions from wealthy clients for a much-needed steady source of income. Even Caillebotte, who inherited a large fortune at age 26 from his wealthy upper-class Parisian family, included decorative works of art in the Impressionist exhibitions in order to obtain commissions.

Camille Pissarro created the fan (above), circa 1882. “The Four Seasons” (below), painted by Pissarro between 1872 and 1873, are believed to have been commissioned by a wealthy businessman and art collector for his home.

If you are planning to travel in Europe and wish to see the finest Impressionist art outside of France, you may want to read up on the collection housed in the Museum Barberini in Potsdam — 30 minutes outside of Berlin — described in our article The Most Magnificent European Display of Monet & Other Impressionists.

You might also enjoy some of the books we recommend, below, revealing how the appreciation of gardens and plein air painting impacted modern art in the 20th century. Thank you for spending time with us at ArtLoversTravel!

“David Hockney: The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020” — Publisher: Royal Academy of Arts (Great Britain). ISBN 9781912520640

“Painting the Modern Garden Monet to Matisse” — Publisher: Royal Academy of Arts (Great Britain). ISBN 9781910350027

“The Artist’s Garden” — Publisher: White Lion Publishing. ISBN 9781781318744

“Matisse Diebenkorn” — Publisher: Prestel. ISBN 9783791355344