The Best Surrealism in Venice and Potsdam

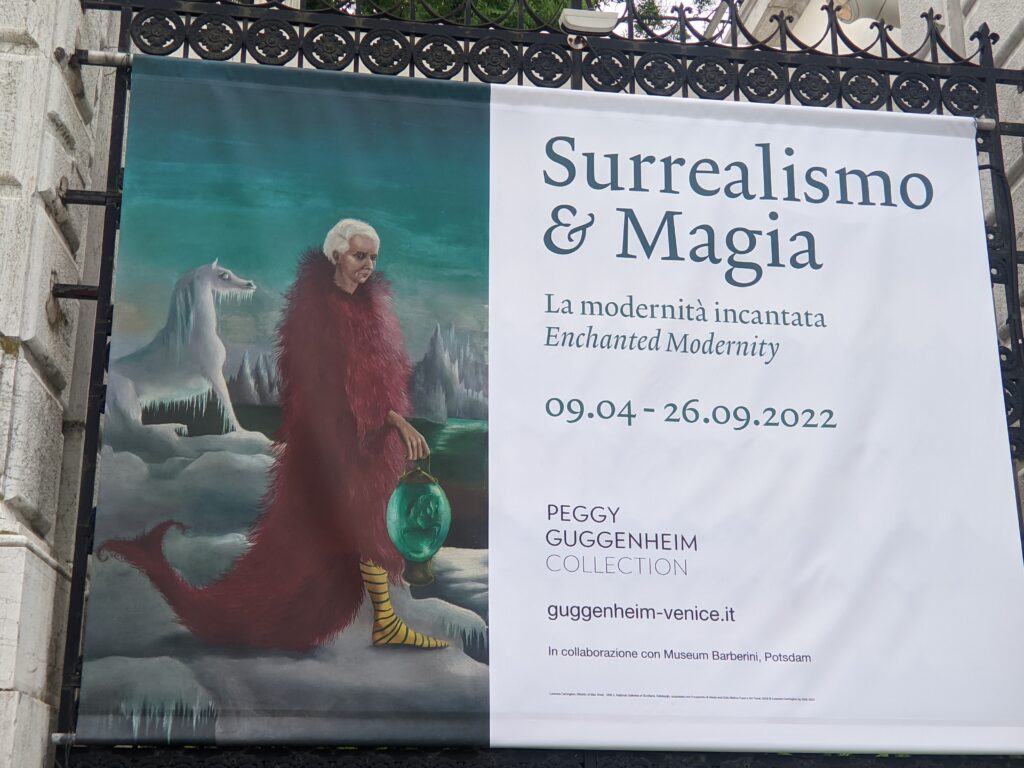

The presentation of “Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity” at the Barberini Museum in Germany (which was on view through January 29, 2023) provided a grand overview of the female and male Surrealists who were active for more than 50 years during the 20th century. The Barberini, where the amazing Hasso Plattner Collection of Impressionism is always on view, is displaying the special exhibition “Clouds and Light: Impressionism from Holland” from July 8 through October 22, 2023.

Surrealist painters imagined fantastical worlds. Through Surrealism, a movement born in France in 1924 and profoundly influenced by the horrors of World War I, writers and visual artists embarked on a novel cultural initiative with the hope of rejuvenating humankind spiritually.

Surrealism in the visual arts may be best described as a rebellion against rationality. In fact, these artists found inspiration in the irrational.

To begin to understand the exhibition “Surrealism and Magic,” which was displayed from April through September 2022 at the Guggenheim Venice, we need to look back in time to the late 1800s in Paris, where there was a revival of mystical practices and interest in the occult — a response, in part, to the swift pace of industrialization in the city. Then, in 1913, Sigmund Freud published “Totem and Taboo,” a collection of four essays (inspired by the work of Wundt and Jung) including “Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts.”

Freud’s description of “magic” as a belief in “the omnipotence of thought” — the idea that human imagination based on inner wishes, fears and dreams directly influences external reality — resonated with the Surrealists.

In his “Second Manifesto of Surrealism” (1929), André Breton called for the “profound … occultation of Surrealism,” embracing a magical process of creation and transformation where the artist becomes the conjurer, the witch. Breton also found inspiration in the metaphysical paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, whose inexplicable compositions on canvas explored mysterious themes, in which irrational dream worlds take on concrete structure and appearance. “The Child’s Brain” (above right) which de Chirico completed in 1914 was a favorite work of art owned by Breton and displayed in his private collection in Paris; Surrealist artists would have viewed this painting when visiting Breton’s home.

Women in Surrealism

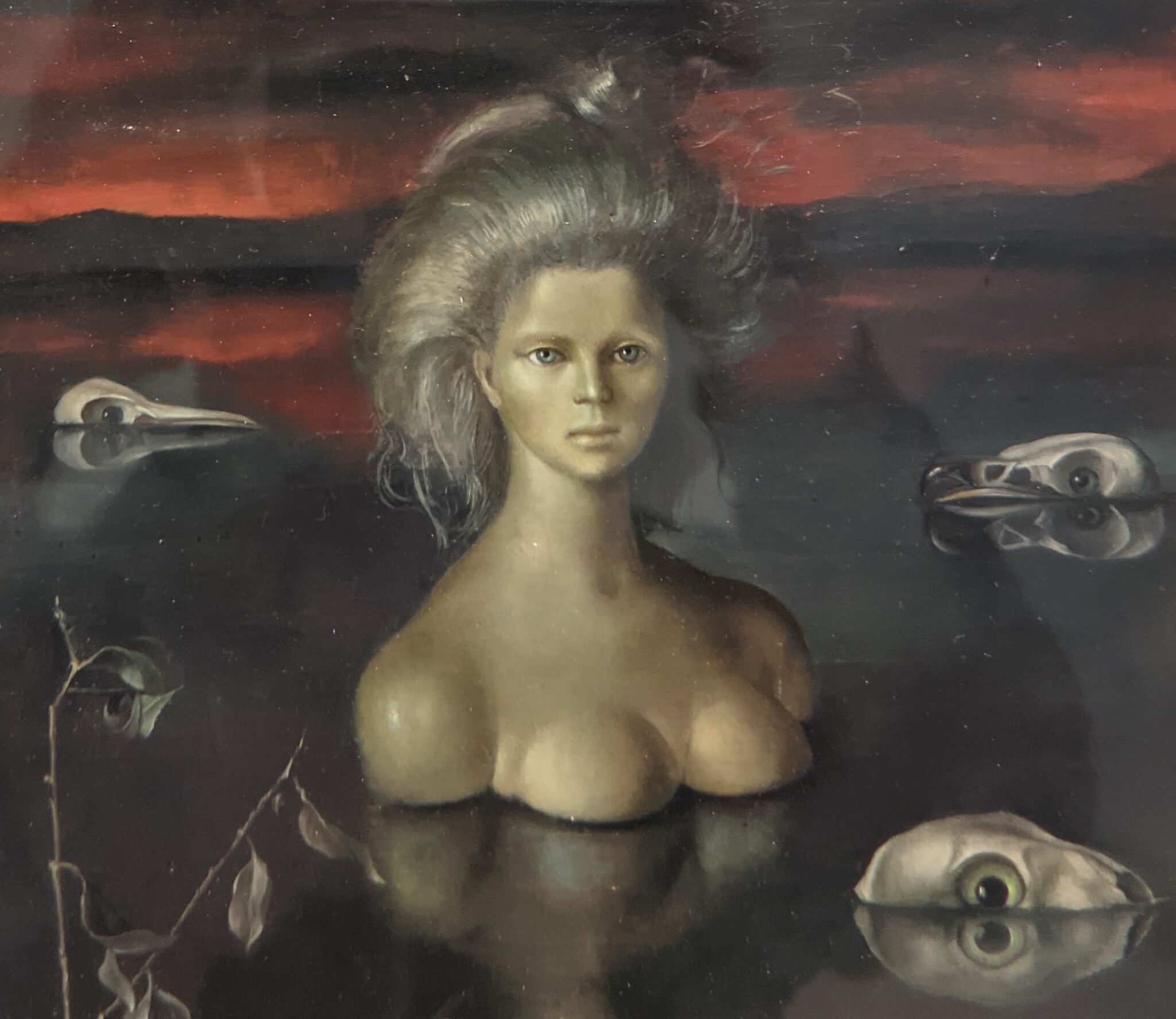

Why is a classically beautiful woman standing against blocks of stone so captivating, and what makes this Magritte painting entitled “Black Magic” (above left) surreal?

The model Georgette Berger was no ordinary woman; Georgette was the artist’s wife. Georgette’s upper body and mind seem as celestial as the perfect blue sky and calm waters, and perhaps her pensive glance reveals her longing to be far from reality. In contrast, René Magritte painted his muse’s earthly lower body with her hand resting upon stone, physically connected to the real world. Therefore, Georgette’s form is split.

Magritte seems to believe the human body is firmly grounded in reality — while the human mind often dwells in the clouds transported far from reality.

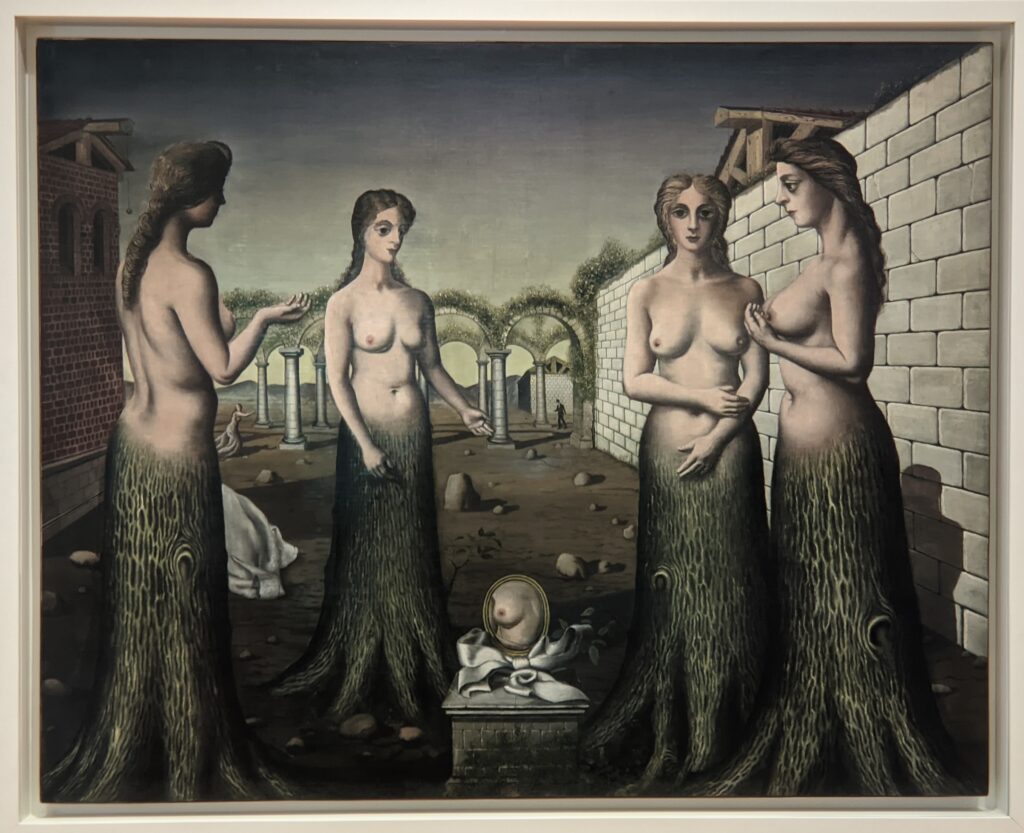

The first generation of male surrealist painters such as André Masson, Paul Delvaux and Magritte (born in 1896, 1897 and 1898, respectively) assigned stereotypical qualities to the women they painted.

These early depictions of women as fertile and sexualized beings, bound to nature, were surprisingly traditional; however, the next generation of male and female surrealist painters referenced matriarchal authority and championed women. As the curators of this exhibition demonstrate, “The Surrealist conception of women was multifaceted, even contradictory: they were deadly, disorderly, erotic, magical, powerful. Often, the significance these female figures assumed hinged on the gender of the artist.”

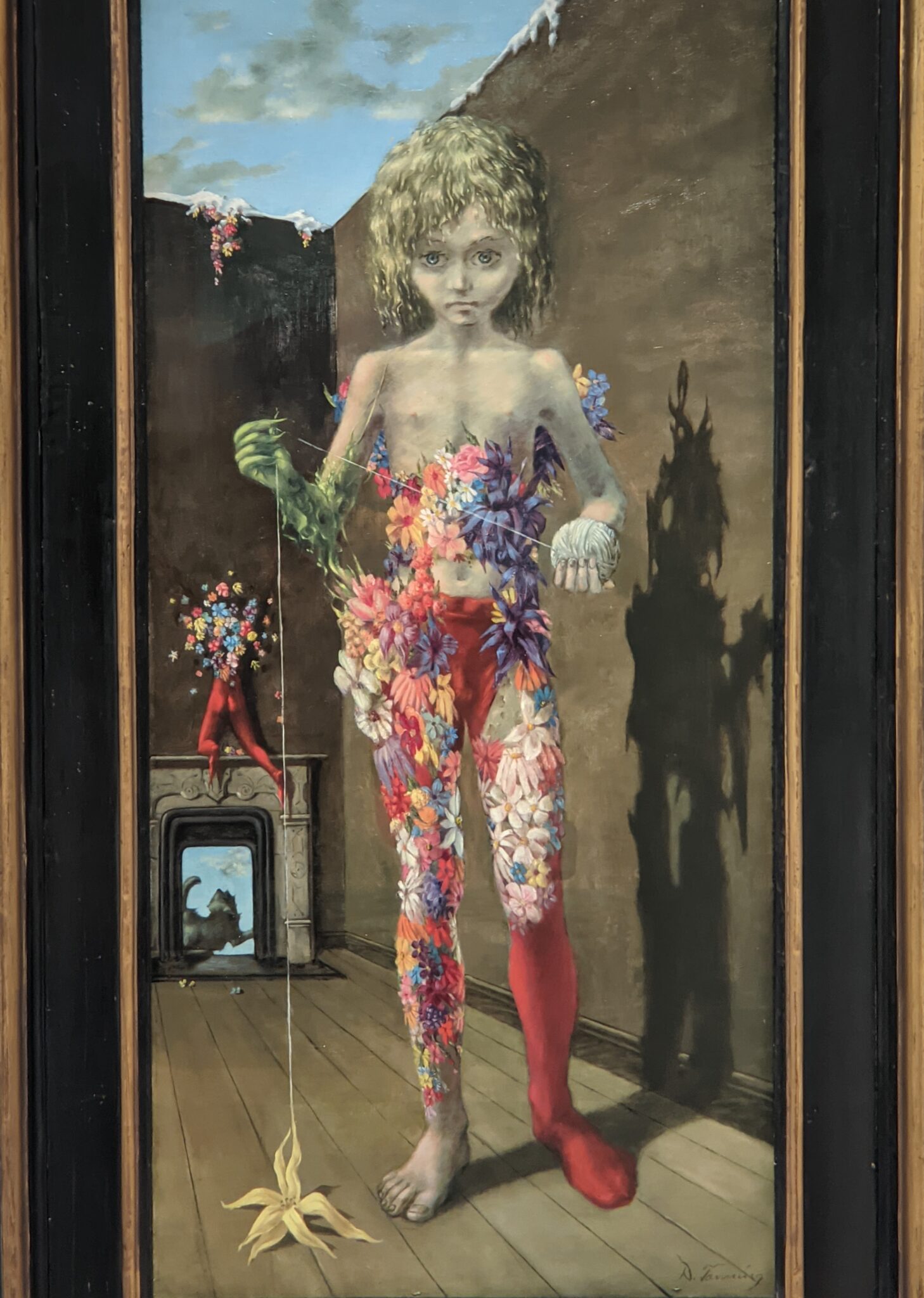

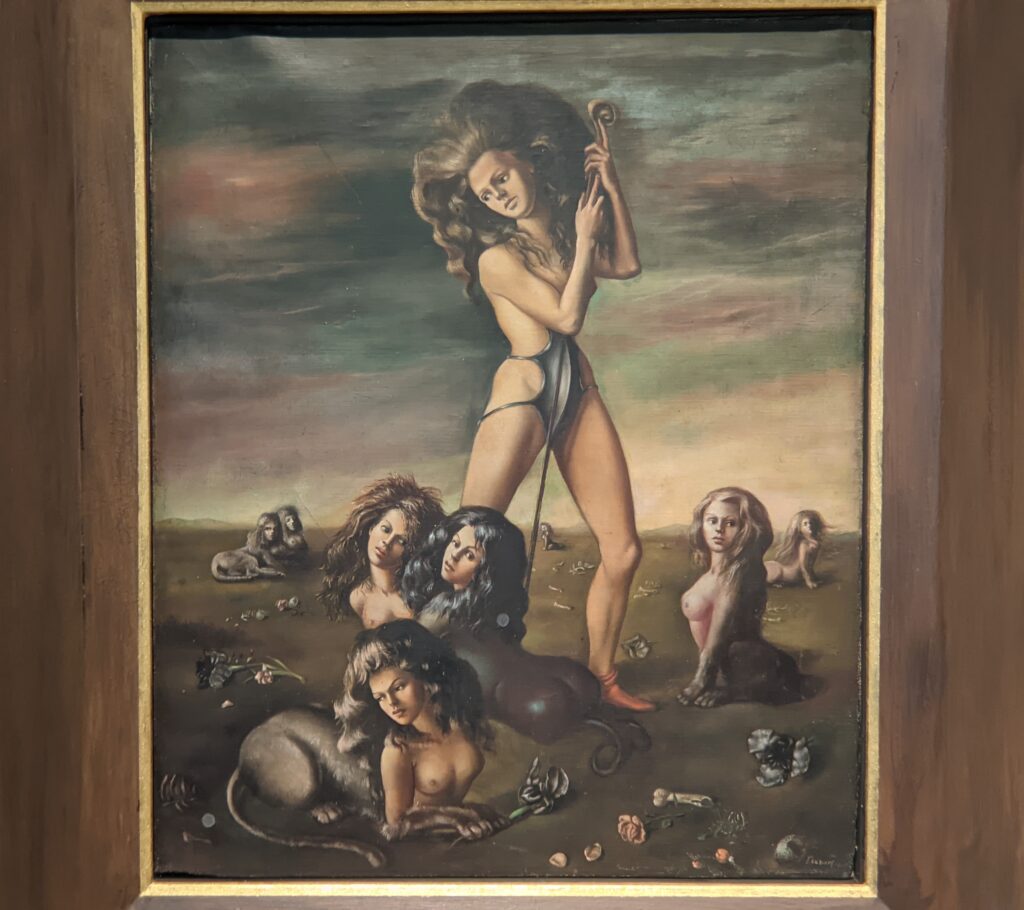

The Argentinian-born Leonor Fini and the American Dorothea Tanning, for example, rejected the notion of women as passive accessories in a male-dominated landscape. At the age of 26, Dorothea Tanning discovered contemporary art from Europe at the Museum of Modern Art’s seminal 1936 exhibition entitled “Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism,” and in 1943 her paintings were included in “Exhibition by 31 Women” at the Art of This Century gallery in New York, owned by Peggy Guggenheim.

Peggy Guggenheim’s decision to host an exhibit exclusively featuring female artists did not receive universal praise. Georgia O’Keeffe declined to participate (noting in a letter she did not want to show as a “woman artist”) and even though “Exhibition by 31 Women” showcased important painters from 16 countries and received positive reviews, it was also the object of chauvinism: a male reviewer from Time magazine refused to cover this art show claiming there were no worthy female artists.

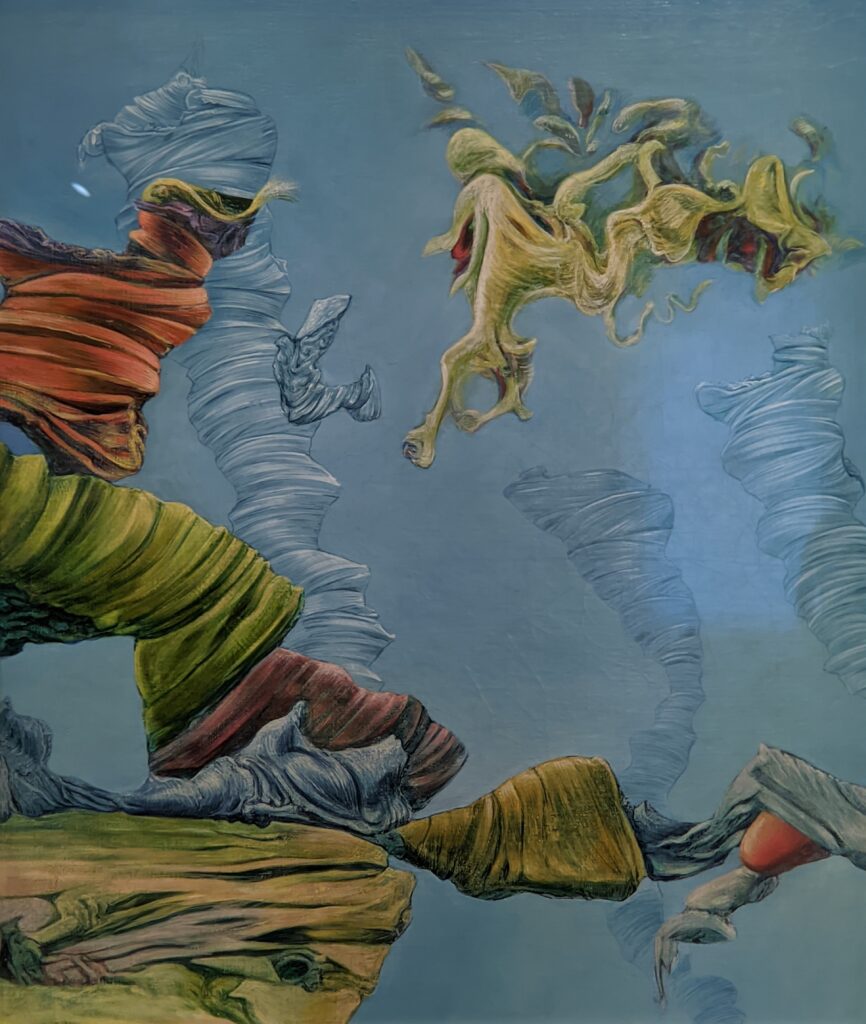

Artists such as Dorothea Tanning and Leonor Fini persevered, transforming their female protagonists into prophetesses, magicians and dangerous mythical beasts such as sphinxes and sirens who craft their own destinies.

Leonora Carrington, Max Ernst & Peggy Guggenheim

In 1937, just before her 20th birthday, Leonora Carrington showed no interest in being introduced at court in Buckingham Palace. Having been expelled from two convent schools as a teenager, Carrington began studying painting, and surrealism became her new passion.

Having seen paintings by Max Ernst at an English exhibition, Carrington was already a fan when she met the German Surrealist painter at a London dinner party. Ernst was a married man, and 27 years older than Leonora Carrington. The two artists promptly traveled to Paris, where Ernst immediately separated from his 2nd wife. The new couple then settled in the South of France.

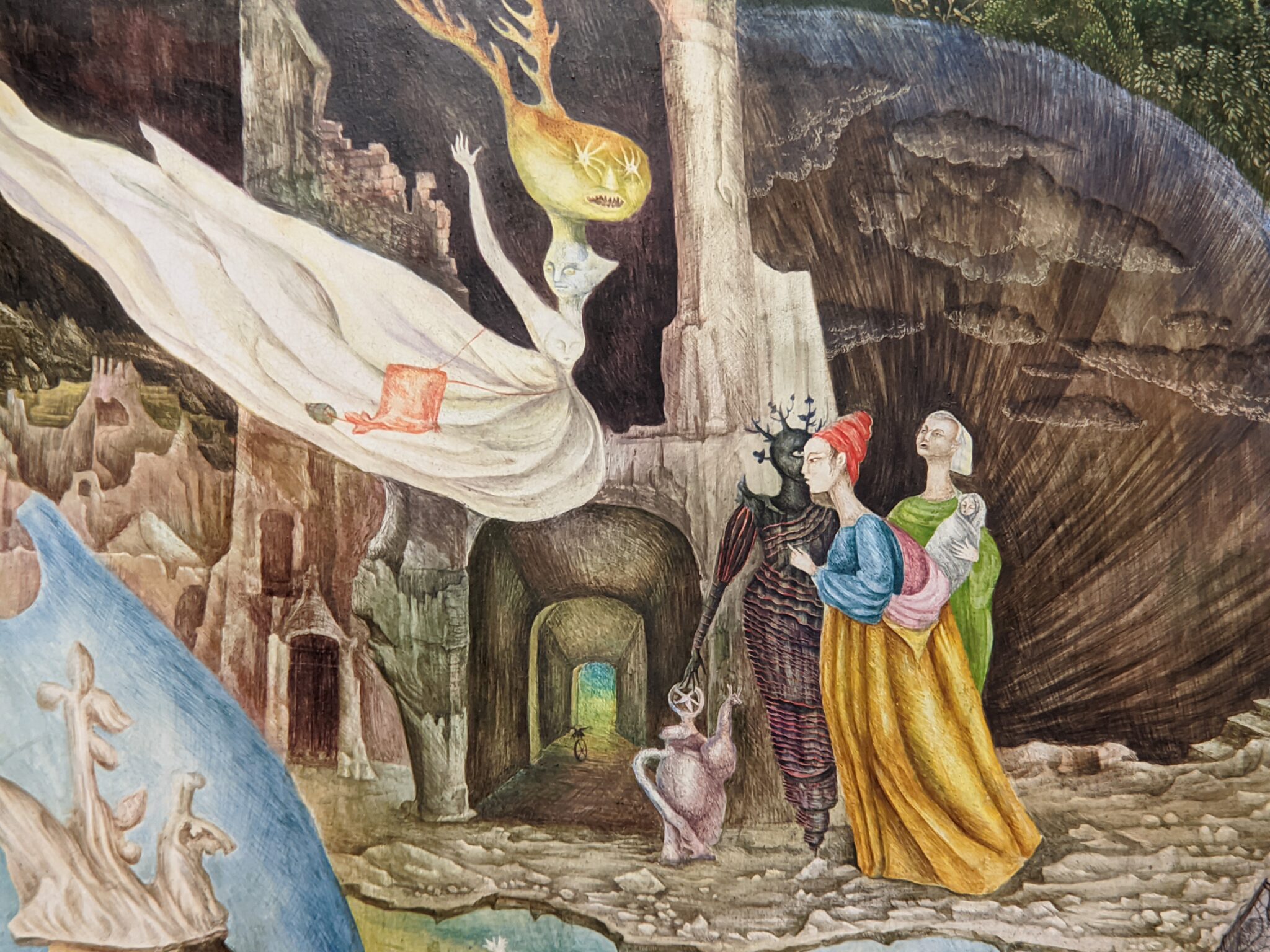

For the next three years Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst supported each other’s creative development, discussed art with their neighbors (Miró, Picasso, and Duchamp, among others) and painted portraits of each other — until World War II disrupted their lives.

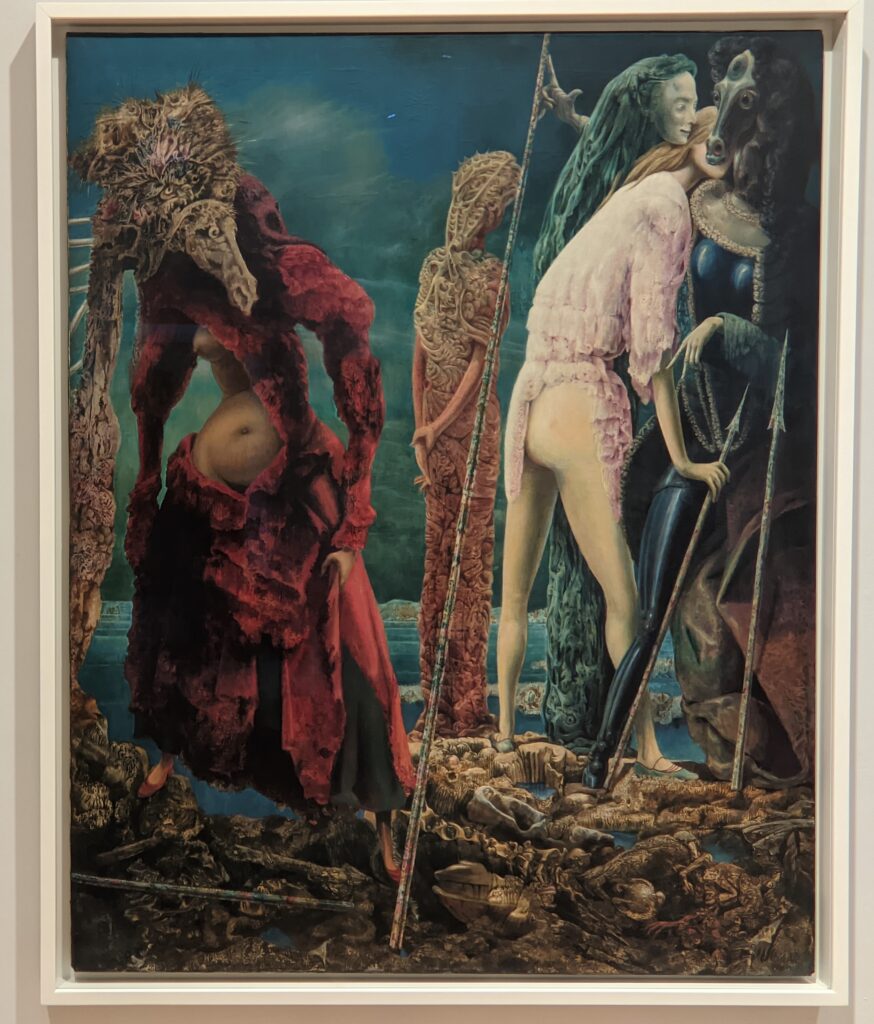

A German national, Max Ernst was first arrested as a “hostile alien” by French authorities and later detained by the Gestapo during the German Occupation since Ernst’s art was considered “degenerate” by the Nazis.

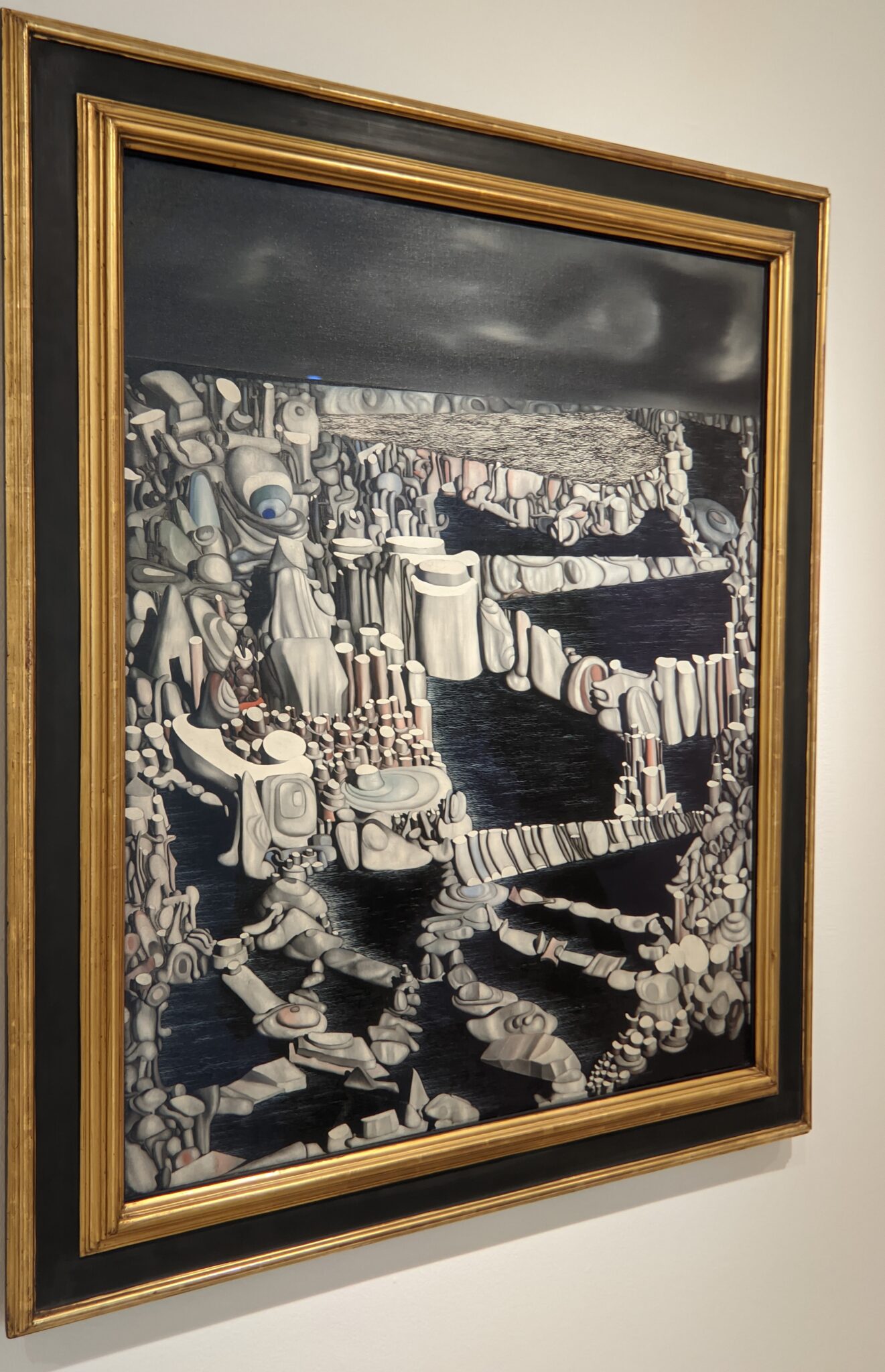

The profound effects of World War II on the Surrealists is referenced in the apocalyptic landscape “Europe After the Rain II” (above), featuring at its center Max Ernst with the head of an avian creature (as if through a magical process of transformation) and Leonora Carrington as his companion with her back to the artist. The physical decay and devastation in this painting — begun by Ernst in France and completed in the United States — also convey the cultural destitution in Europe which resulted from Fascism.

Max Ernst managed to escape France, leaving Carrington behind, with the assistance of the arts patron Peggy Guggenheim. Guggenheim, an American heiress, had acquired numerous paintings by Ernst in 1938, which she displayed in her London gallery.

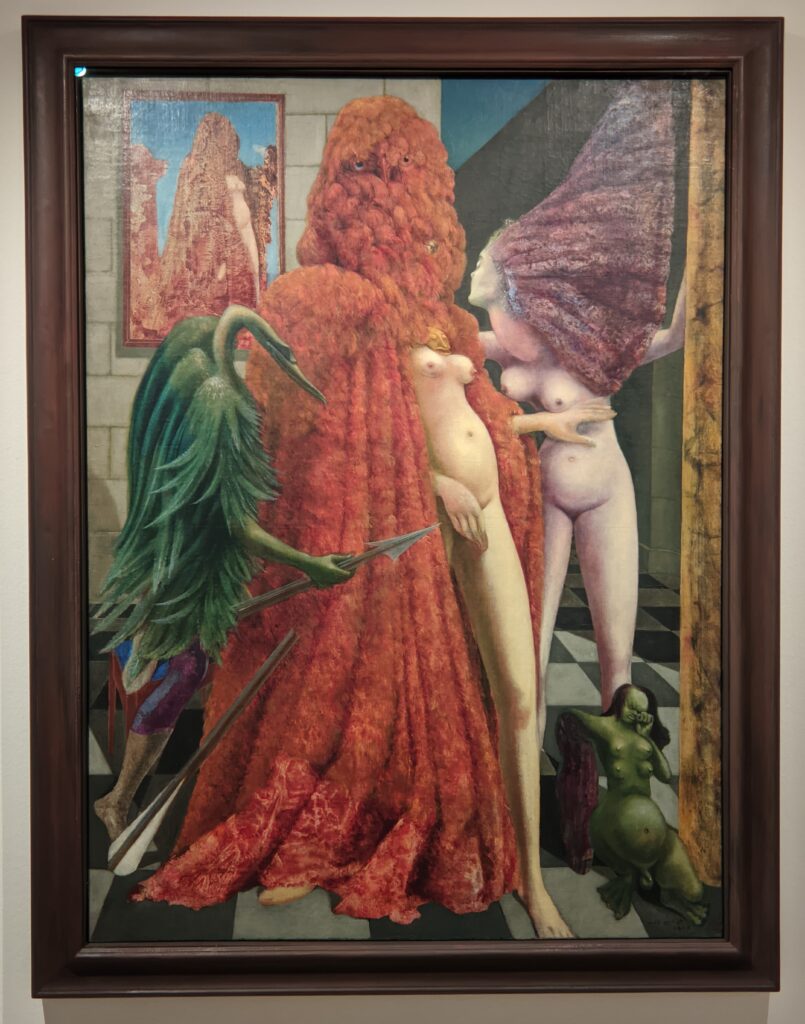

Peggy Guggenheim and Max Ernst were married from 1942 to 1946; the marriage, however, did not last. Ernst married Dorothea Tanning in 1946 and they remained together until his death in 1976.

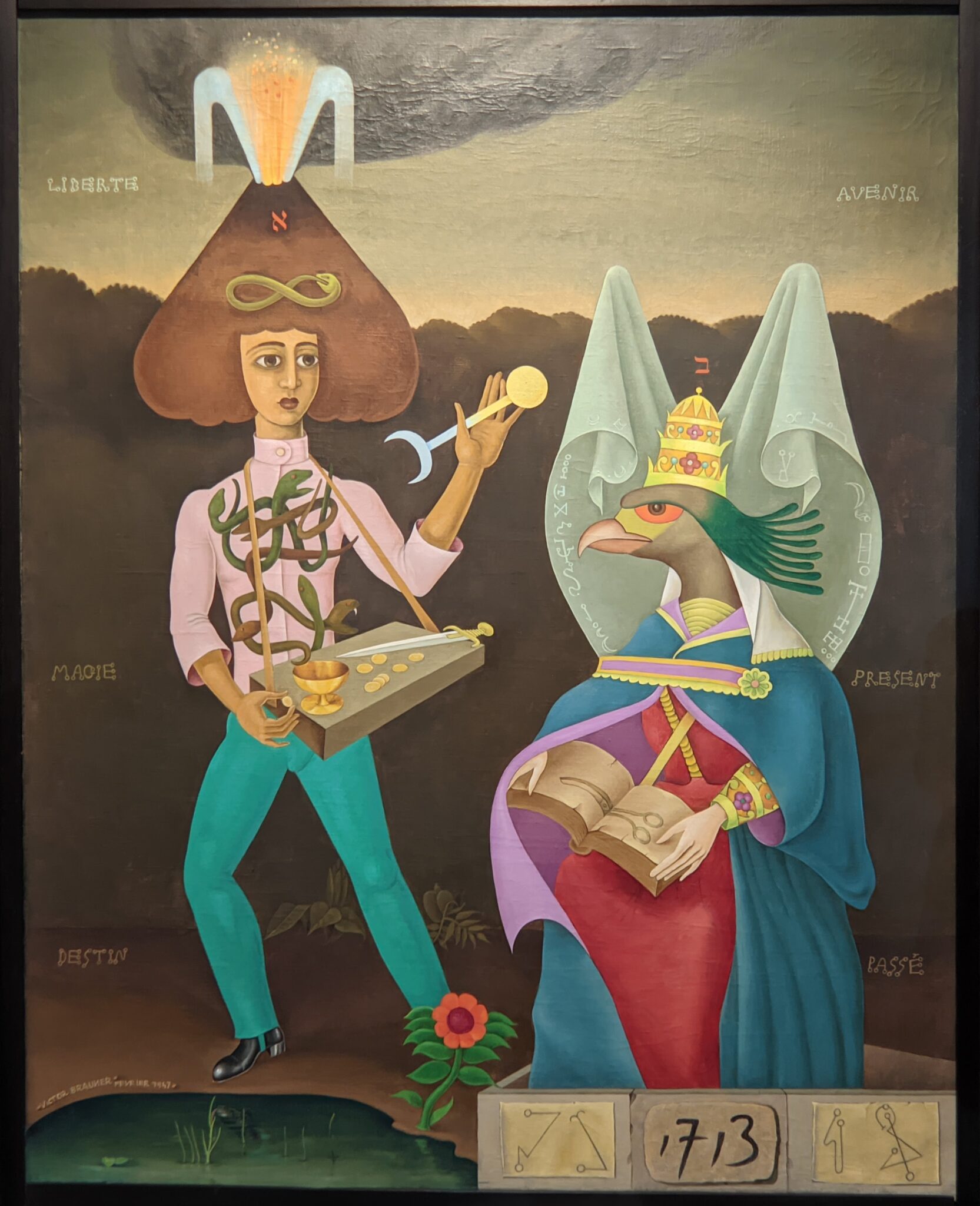

Magic is “the means of approaching the unknown by other ways than those of science or religion.”

Max Ernst

With the release of his first treatise “Manifesto of Surrealism” in 1924, the writer André Breton marked his definitive break from Dada and founded an international literary/artistic movement based on defiance and a desire for revolutionary thought. Rather than pursuing anarchic means, the Surrealists (under Breton’s leadership) sought a productive expression of the movement’s convictions through dream interpretation, automatic writing and exploration of the subconscious.

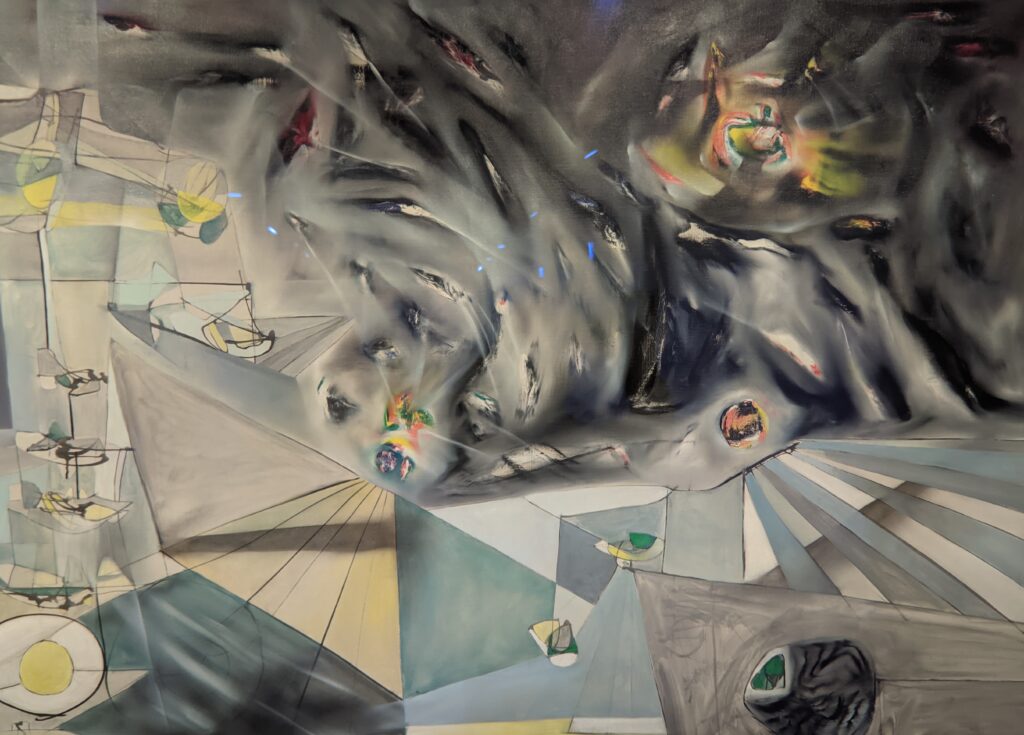

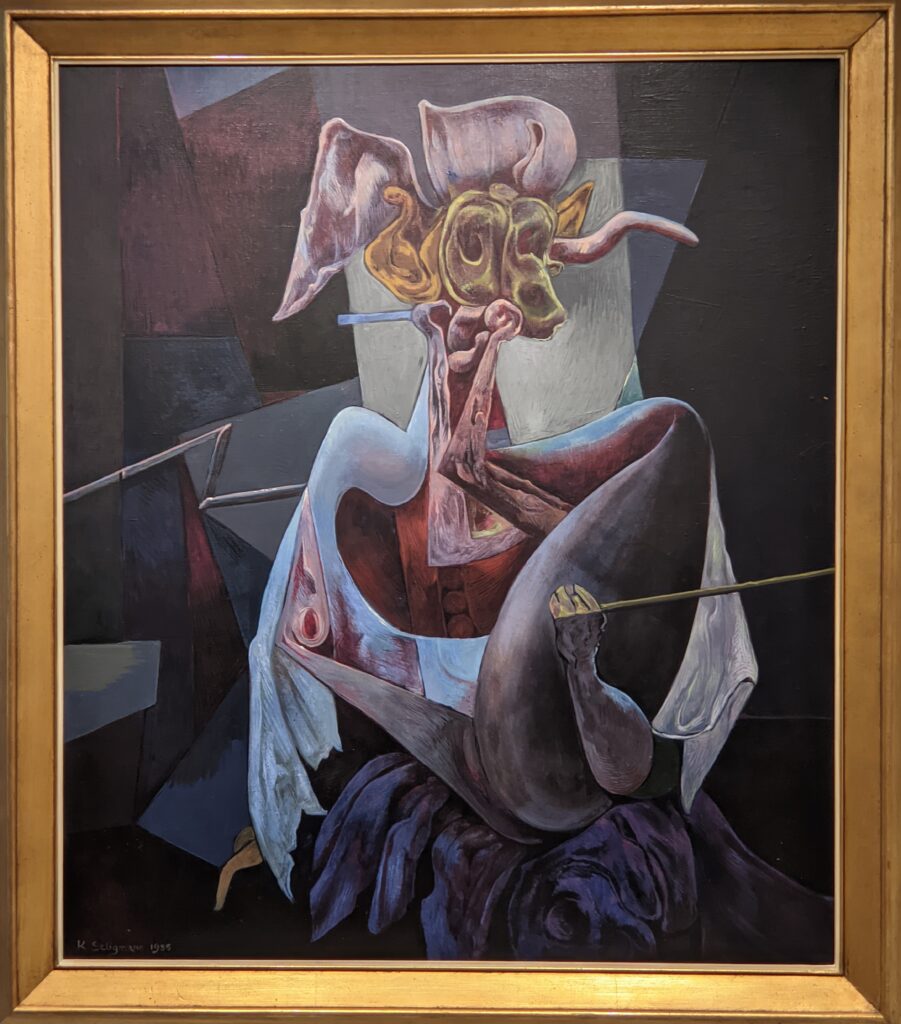

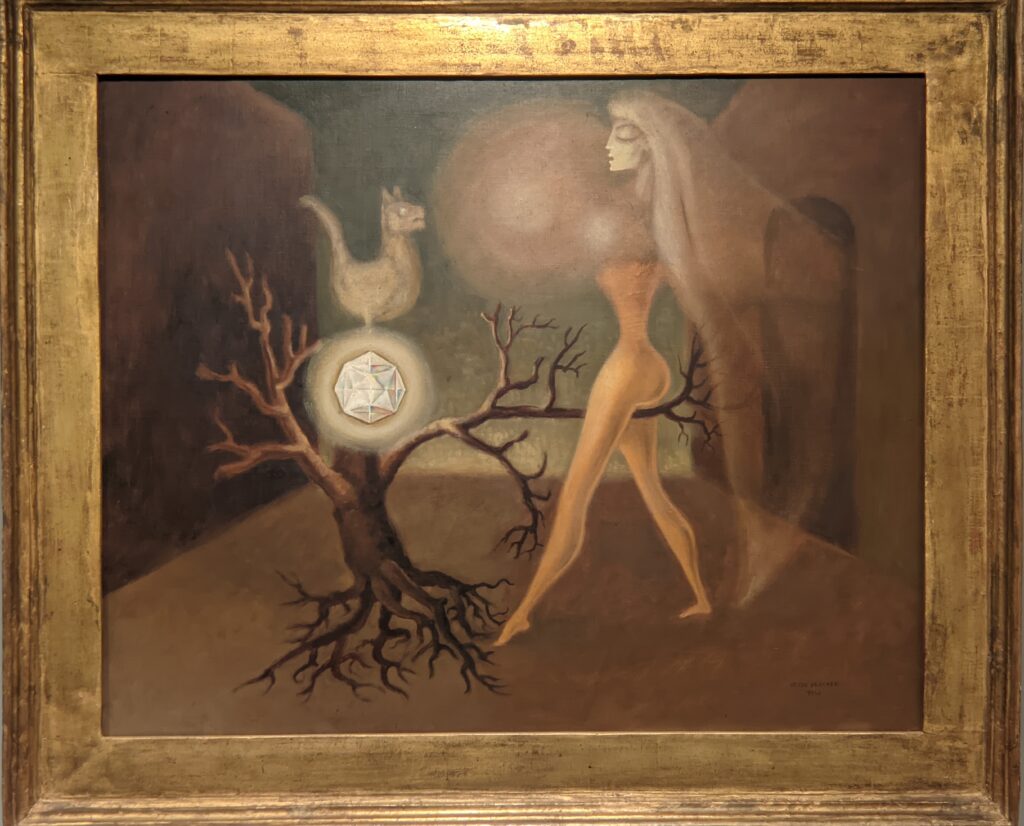

Unlike the major art movements that preceded Surrealism — Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism and De Stijl — no one specific style can be said to characterize all the Surrealist painters. At the time Dorothea Tanning was exploring the subject of metamorphosis and the constant flux between the unconscious self and the natural realm, for example, André Masson was looking back to German Romantic authors such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe for inspiration.

Therefore, there were several themes that interested and at times united these artists.

Romanticism was an intellectual movement in literature, the visual arts and music which peaked in prominence between 1800 and 1850. Interest in human psychology, the natural world and the expression of personal feelings based on intuition and imagination (rather than facts) distinguished Romanticism from previous trends.

The Surrealist program was also marked by pessimism following the horrific experiences of World Wars I and II.

From its inception, between the great wars, the revolutionary spirit of Surrealism led to an exploration of the darker side of the human psyche, such as violence, death, sexual perversion/cruelty and suicide, as well as an anticlerical, blasphemous revolt against religious constraints.

In the context of the World Wars, many painters tried to stimulate and free their minds from limitations by embracing magic and occultism (derived from the Latin occultus, meaning “concealed”).

Occultism, a belief in mystical forces in the universe that are hidden from sight, was seen as a means of fulfilling the goal of individual transformation and total revolution.

The Profound Occultation of Surrealism

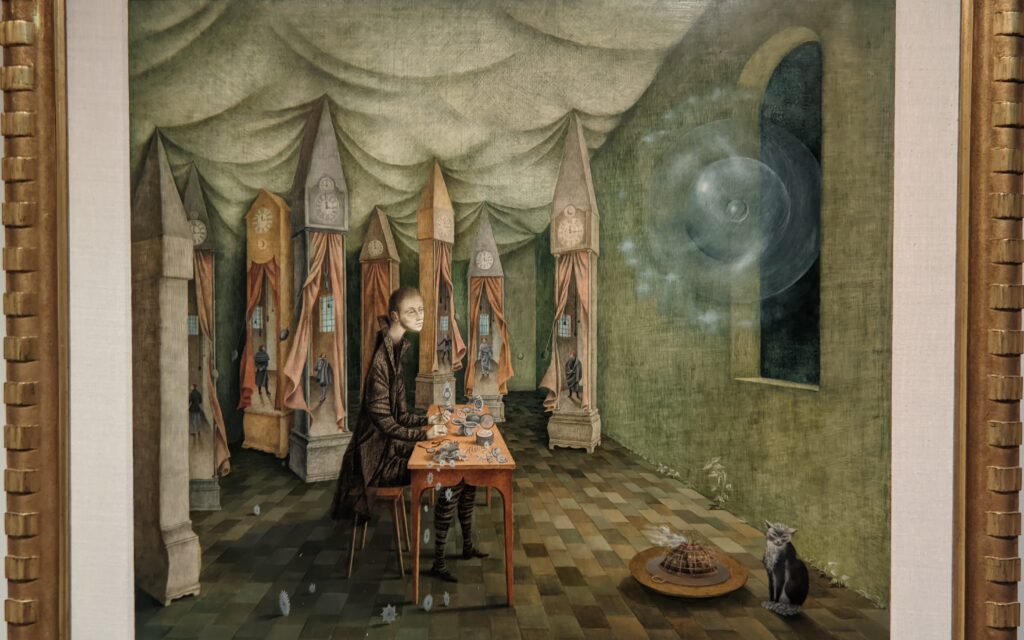

From the time of the publication of the Second Manifesto of Surrealism (1929) — in which Breton called for the “profound … occultation of Surrealism” — many painters within the group embraced magic, alchemy and the occult. This interest in alchemy (a magical process of creation and transformation based on astrology, witchcraft, potions and other medieval forerunners of chemistry) was an ongoing endeavor that reached its apogee after World War II. “The dream world and the real world are the same,” declared the Catalan-born painter Remedios Varo.

In 1941, Remedios Varo fled Fascism in Spain and Nazi-occupied France by emigrating to Mexico, where she joined Leonora Carrington and other expatriate intellectuals from Europe.

The Apex of this Exhibition: Amazing Paintings by Leonora Carrington

Left devastated in France from her abandonment by Max Ernst in 1941, Leonora Carrington moved to Spain where she suffered a nervous breakdown. Her father had her committed to a mental institution, where Carrington endured shock therapy, assault and experimental drugs. Carrington managed to escape life in an asylum and make her way to Mexico City, where she spent the remainder of her amazingly productive life. “Of the two, I was far more afraid of my father than I was of Hitler,” she said.

Leonora Carrington (1917 — 2011) lived most of her adult life in Mexico City. While the Surrealist movement symbolized the avant-garde for several decades, many artists involved in Surrealism regarded women as muses — not as artists in their own right.

It is fair to say that most Surrealists explored the possibilities opened up by Sigmund Freud regarding the subconscious mind, and many painters interpreted “the omnipotence of thought” to mean pure thought uncensored by moral, religious, political and rational principles.

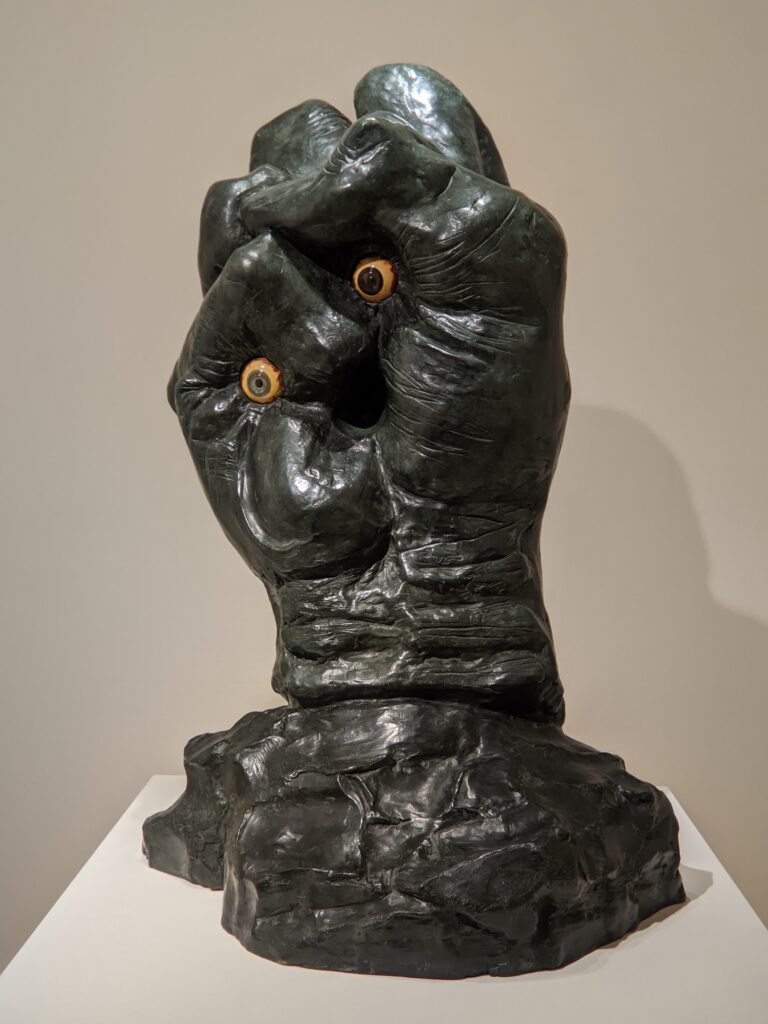

Carrington had no interest in the writings of Freud. Instead, like Frida Kahlo (1907 — 1954) Carrington employed autobiographical details and symbolism as subjects for her paintings and sculpture. “I painted for myself … I never believed anyone would exhibit or buy my work,” Carrington once said. In 2005, Christie’s auctioned El Juglar (The Juggler), Carrington’s 1954 oil on canvas, for $713,000 — setting a new record for the highest price paid for art by a living Surrealist painter. Carrington is also appreciated as a novelist and one of the most important founding members of the women’s liberation movement in Mexico.

The Duality of the Self

Please remember, even though the exhibition “Surrealism & Magic: Enchanted Modernity” closed in Potsdam in January 2023, the Museum Barberini houses a fabulous permanent collection which is open to the public from Wednesday through Monday from 10:00 until 19:00. Closed on Tuesdays. Please check their website for information on the museum’s special exhibitions and opening hours (especially from December 24 through January 1).

Whether or not you consider yourself an admirer of Surrealism, the quality of this past exhibit was top-notch!

While this show attempted to delve into the elusive realm of the “surreal” and the conjuring of wondrous worlds, we found the true (and perhaps unintended) focus of the exhibition to be the women artists who challenged and subverted the traditional perception of male dominance in the Surrealist movement.

Dorothea Tanning, Leonor Fini and Leonora Carrington explored the duality that comes with being creative women within a sexist movement. These artists were interested in presenting female sexuality as they experienced it, rather than as their male counterparts characterized female sexuality and objectified the usefulness of women. You will notice that most of the women depicted in paintings by Tanning, Fini and Carrington cast intimidating shadows, look piercingly at the viewer, appear effectual, and glance into mirrors — recognizing the duality that they are simultaneously the observed and the observers.

DEDICATION

We want to thank our friend Maddalena Vassena for her gracious assistance & hospitality during our visit to the Veneto region of Italy.

ART LOVER’S TIP: The Veneto region is one of the most scenic & special destinations in Europe. Unfortunately, the enchanting City of Venice is often extremely expensive and overcrowded. As an alternative to spending a week in the City of Venice, you might consider 3 days in Venice and 4+ days exploring and relaxing in the Dolomites. A perfect base from which to explore the mountain and lake district 2 hours north of Venice Airport is Cortina d’Ampezzo, an Alpine town in the Province of Belluno. We recommend the Cristallo, a Luxury Collection resort & spa in the heart of Cortina d’Ampezzo for year-round pleasure.

Potsdam, Germany

Sanssouci Palace & the Hasso Plattner Collection

In one day it is quite easy to visit both the royal palace at Sanssouci and see the phenomenal collection of Impressionist paintings inside the Museum Barberini. For highlights from the Hasso Plattner Collection, you may want to read our article entitled “The Most Magnificent European Display of Monet & Other Impressionists“.